Through the Portal and Into the Quest: Robert Jordan's the Wheel of Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acclaiming the Future

Name: Anouk van der Zee Student number: 3467449 Format: Bachelor thesis Supervisor: dr. Barnita Bagchi Acclaiming the Future A Critical Analysis of the Contemporary Value of High Fantasy Literature Foreword to this thesis I took the opportunity to write about a genre I feel passionate about for this thesis. As I started to look for secondary literature to support my analyses, what I found was almost completely based on related topics, not much on high fantasy itself. Especially on the subject of the fan- tastic, which is close but ultimately not relevant to my choice of genre. I’ve used one line from Todorov’s The Fantastic—almost the go-to work for literary critics interested in this area—in all, and it was a quote from another text to support the claim that the fantastic differs from the marvellous, on which high fantasy is built. As I started to worry about the sustainability of my own thesis, I realised that this is my topic. Consider everything that has been allowed to wear the tag of literature in the last few decades. Some of these definitely fall into the popular or cult category, yet are given serious considera- tion. Not high fantasy, as if the genre were already dead and buried with no other frontrunner than Tolkien. But when a genre—any genre—is still alive, turning out novels and having pu- blishers especially devoted to it (such as Tor Books), literary criticism cannot assume that no other literary work will be turned out. Therefore, its quiet refusal to pay serious attention to the genre is incomprehensible, even unreasonable, and has created a very dismissive atmos- phere—from the critics down to the mainstream reader public. -

On Ways of Studying Tolkien: Notes Toward a Better (Epic) Fantasy Criticism

Journal of Tolkien Research Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 2 2020 On Ways of Studying Tolkien: Notes Toward a Better (Epic) Fantasy Criticism Dennis Wilson Wise University of Arizona, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Wise, Dennis Wilson (2020) "On Ways of Studying Tolkien: Notes Toward a Better (Epic) Fantasy Criticism," Journal of Tolkien Research: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch/vol9/iss1/2 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Christopher Center Library at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Tolkien Research by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Wise: On Ways of Studying Tolkien INTRODUCTION We are currently living a golden age for Tolkien Studies. The field is booming: two peer-reviewed journals dedicated to J.R.R. Tolkien alone, at least four journals dedicated to the Inklings more generally, innumerable society newsletters and bulletins, and new books and edited collections every year. And this only encompasses the Tolkien work in English. In the last two decades, specifically since 2000, the search term “Tolkien” pulls up nearly 1,200 hits on the MLA International Bibliography. For comparison, C. S. Lewis places a distant second at fewer than 900 hits, but even this number outranks the combined hits on Ursula K. -

Readercon 14

readercon 14 program guide The conference on imaginative literature, fourteenth edition readercon 14 The Boston Marriott Burlington Burlington, Massachusetts 12th-14th July 2002 Guests of Honor: Octavia E. Butler Gwyneth Jones Memorial GoH: John Brunner program guide Practical Information......................................................................................... 1 Readercon 14 Committee................................................................................... 2 Hotel Map.......................................................................................................... 4 Bookshop Dealers...............................................................................................5 Readercon 14 Guests..........................................................................................6 Readercon 14: The Program.............................................................................. 7 Friday..................................................................................................... 8 Saturday................................................................................................14 Sunday................................................................................................. 21 Readercon 15 Advertisement.......................................................................... 26 About the Program Participants......................................................................27 Program Grids...........................................Back Cover and Inside Back Cover Cover -

Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: a Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-7-2012 Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant James H. Shimkus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Shimkus, James H., "Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING SPECULATIVE FICTION IN COLLEGE: A PEDAGOGY FOR MAKING ENGLISH STUDIES RELEVANT by JAMES HAMMOND SHIMKUS Under the Direction of Dr. Elizabeth Burmester ABSTRACT Speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) has steadily gained popularity both in culture and as a subject for study in college. While many helpful resources on teaching a particular genre or teaching particular texts within a genre exist, college teachers who have not previously taught science fiction, fantasy, or horror will benefit from a broader pedagogical overview of speculative fiction, and that is what this resource provides. Teachers who have previously taught speculative fiction may also benefit from the selection of alternative texts presented here. This resource includes an argument for the consideration of more speculative fiction in college English classes, whether in composition, literature, or creative writing, as well as overviews of the main theoretical discussions and definitions of each genre. -

The Class That Made It Big Brandon Sanderson Leading Edge Success Stories 35, M 8 December 2011 Former Editor Chen’S Noodle Shop, Orem, UT Future Professor

The Class that Made It Big Brandon Sanderson Leading Edge Success Stories 35, M 8 December 2011 Former Editor Chen’s Noodle Shop, Orem, UT Future Professor Dan Wells Peter Ahlstrom Karen Ahlstrom 34, M 35, M 34, F Former Editor Former Editor First LE Webmaster Stranger Stranger Stranger Personal Data: Brandon Sanderson is the bestselling author of the Mistborn series, and is finishing Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time epic. He also teaches Engl 318R (How to Write Science Fiction and Fantasy) at BYU every winter semester. Dan Wells is the bestselling author of the I Am Not a Serial Killer trilogy. Peter Ahlstrom is Brandon’s personal assistant, and Karen is Peter’s wife. All four of them worked on Leading Edge at the same time. Special thanks to Emily Sanderson, Brandon’s wife, who watched the Ahlstrom daughters so that both Karen and Peter could attend this interview. Social Data: The trick to getting people to do things for you in the real world is to take them out to lunch. We met together at Chen’s Noodle House, a Chinese restaurant in Orem, UT (the place was Dan Wells’ idea). There is an authentic Chinese theme in the restaurant, right down to statues, chopsticks, and Chinese ambiance music. There were other customers in the restaurant at the time (though not too many), as well as wait staff &c. Cultural Data: “TLE” is this generation’s acronym for The Leading Edge, as it was called at that time. Quark Xpress is an older design layout program that has since been replaced in the university curriculum by Adobe InDesign. -

Teen Tech Week Book List

Leviathan by Scott Westerfeld YA FIC Westerfeld In an alternate 1914 Europe, fifteen-year- old Austrian Prince Alek, on the run from the Clanker Powers who are attempting to take over the globe using mechanical ma- chinery, forms an uneasy alliance with Deryn who, disguised as a boy to join the British Air Service, is learning to fly genet- ically-engineered beasts. (1st in Leviathan Series) Teen Tech Find us, like us, follow us! Week Book List Malverne Public STEAMPUNK Behemoth by Scott Westerfeld Library Youth Service YA FIC Westerfeld Continues the story of Austrian Prince Alek who, in an alternate 1914 Europe, eludes the Germans by traveling in the Leviathan to Constantinople, where he faces a @MalvernePL whole new kind of genetically-engineered warships. (2nd in Leviathan Series) Goliath by Scott Westerfeld YA FIC Westerfeld Malverne Public Library Alek and Deryn encounter obstacles on 61 St. Thomas Place February 2014 the last leg of their round-the-world quest Malverne, NY 11565 to end World War I, reclaim Alek's throne (516) 599-0750 as prince of Austria, and finally fall in love. Malvernelibrary.org (3rd in Leviathan Series) The Unnaturalists by Tiffany Trent YA FIC Trent Steampunk! An Anthology of Fantastically Vespa Nyx wants nothing more than to spend Rich and Strange Stories edited by Kelly Link and Gavin J. Grant the rest of her life cataloging Unnatural crea- YA SS Steampunk tures in her father's museum, but as she gets A collection of fourteen fantasy stories by older, the requirement to become a lady and well-known authors, set in the age of steam find a husband is looming large over her. -

(2019): 149-175. the Journal of English and Germanic Philology

1 TIMOTHY S. MILLER (T. S. MILLER) Department of English Florida Atlantic University CU Ste. 306 777 Glades Road Boca Raton, FL 33431-0991 [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. in English, University of Notre Dame, 2014 Bachelor of Arts in English and in Classics, Kenyon College, 2008 EMPLOYMENT AND MAJOR FELLOWSHIPS Florida Atlantic University, Assistant Professor of English, 2020-present Marquette University, Lecturer in English, 2019-2020 Sarah Lawrence College, Guest Faculty in Literature, 2014-2018 Mercy College, Adjunct Professor of Seminars, 2016-2018 Mellon/ACLS Dissertation Completion Fellowship, 2013-2014 Notebaert Premier Fellowship, University of Notre Dame, 2008-2013 SELECTED PUBLICATIONS "Speculative Fiction and the Contemporary Novel." Forthcoming in The Cambridge Handbook of Literature and Plants. Ed. Bonnie Lander Johnson. Cambridge University Press. "Medicine in Proto-Science Fiction." Forthcoming in The Edinburgh Companion to Science Fiction and the Medical Humanities. Ed. Gavin Miller, with Joan Haran, Donna McCormack, and Anna McFarlane. Edinburgh University Press. "'[I]n plauntes lyf is yhud': Botanical Metaphor and Botanical Science in Middle English Literature." Forthcoming in Medieval Ecocriticisms, ed. Heide Estes. Amsterdam University Press. "Vegetable Love: Desire, Feeling, and Sexuality in Botanical Fiction." Plants in Science Fiction: Speculative Vegetation. Ed. Katherine Bishop, Jerry Määttä, and David Higgins. Cardiff: the University of Wales Press, 2020. 105-126. "Bidding with Beowulf, Dicing with Chaucer, and Playing Poker with King Arthur: Medievalism in Modern Board Gaming Culture." Studies in Medievalism XXVIII: Medievalism and Discrimination (2019): 149-175. "Precarity, Parenthood, and Play in Jennifer Phang's Advantageous." Science Fiction Film & Television 11.2 (2018): 177-201 [special issue on Women & Science Fiction Media]. -

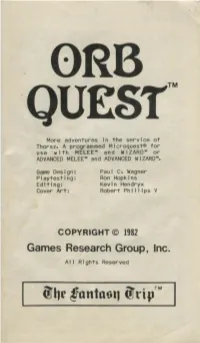

ORB QUEST™ Is a Programmed Adventure for the Instruction, It W I 11 Give You Information and FANTASY TRIP™ Game System

0RB QUEST™ More adventures in the service of Thorsz. A programmed Microquest® for use with ME LEE'" and WIZARD'" or ADVANCED MELEE'" and ADVANCED WIZARD'". Game Design: Paul c. Wagner Playtesting: Ron Hopkins Editing: Kevin Hendryx Cover Art: Robert Phillips V COPYRIGHT© 1982 Games Research Group, Inc. Al I Rights Reserved 3 2 from agai~ Enough prospered, however, to establish INTRODUCTION the base of the kingdom and dynasty of the Thorsz as it now stands. During evening rounds outside the w i. zard's "With time and the excess of luxuries brought quarters at the Thorsz's pa I ace, you are. deta 1 n~~ b~ about by these successes, the fate of the ear I i er a red-robed figure who speaks to you 1 n a su ue orbs was forgotten. Too many were content with tone. "There is a task that needs to _be done," their lot and power of the present and did not look murmurs the mage, "which is I~ the service of the forward into the future. And now, disturbing news Thorsz. It is fu I I of hardsh 1 ps and d~ngers, but Indeed has deve I oped. your rewards and renown w i I I be accord 1 ng I Y great. "The I and surrounding the rea I ms of the Thorsz Wi II you accept this bidding?" has become darker, more foreboding, and more With a silent nod you agree. dangerous. One in five patrols of the border guard "Good," mutters the wizard. "Here 1 s a to~en to returns with injury, or not at al I. -

Toward a Theory of the Dark Fantastic: the Role of Racial Difference in Young Adult Speculative Fiction and Media

Journal of Language and Literacy Education Vol. 14 Issue 1—Spring 2018 Toward a Theory of the Dark Fantastic: The Role of Racial Difference in Young Adult Speculative Fiction and Media Ebony Elizabeth Thomas Abstract: Humans read and listen to stories not only to be informed but also as a way to enter worlds that are not like our own. Stories provide mirrors, windows, and doors into other existences, both real and imagined. A sense of the infinite possibilities inherent in fairy tales, fantasy, science fiction, comics, and graphic novels draws children, teens, and adults from all backgrounds to speculative fiction – also known as the fantastic. However, when people of color seek passageways into &the fantastic, we often discover that the doors are barred. Even the very act of dreaming of worlds-that-never-were can be challenging when the known world does not provide many liberatory spaces. The dark fantastic cycle posits that the presence of Black characters in mainstream speculative fiction creates a dilemma. The way that this dilemma is most often resolved is by enacting violence against the character, who then haunts the narrative. This is what readers of the fantastic expect, for it mirrors the spectacle of symbolic violence against the Dark Other in our own world. Moving through spectacle, hesitation, violence, and haunting, the dark fantastic cycle is only interrupted through emancipation – transforming objectified Dark Others into agentive Dark Ones. Yet the success of new narratives fromBlack Panther in the Marvel Cinematic universe, the recent Hugo Awards won by N.K. Jemisin and Nnedi Okorafor, and the blossoming of Afrofuturistic and Black fantastic tales prove that all people need new mythologies – new “stories about stories.” In addition to amplifying diverse fantasy, liberating the rest of the fantastic from its fear and loathing of darkness and Dark Others is essential. -

Clockwork Heroines: Female Characters in Steampunk Literature Cassie N

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by TopSCHOLAR Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School 5-1-2013 Clockwork Heroines: Female Characters in Steampunk Literature Cassie N. Bergman Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Bergman, Cassie N., "Clockwork Heroines: Female Characters in Steampunk Literature" (2013). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 1266. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1266 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLOCKWORK HEROINES: FEMALE CHARACTERS IN STEAMPUNK LITERATURE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English Western Kentucky University Bowling Green Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Arts By Cassie N. Bergman August 2013 To my parents, John and Linda Bergman, for their endless support and love. and To my brother Johnny—my best friend. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Johnny for agreeing to continue our academic careers at the same university. I hope the white squirrels, International Fridays, random road trips, movie nights, and “get out of my brain” scenarios made the last two years meaningful. Thank you to my parents for always believing in me. A huge thank you to my family members that continue to support and love me unconditionally: Krystle, Dee, Jaime, Ashley, Lauren, Jeremy, Rhonda, Christian, Anthony, Logan, and baby Parker. -

Chapter Two Unravelling the Pattern: the Magus Figures in the Wheel Of

89 Chapter Two Unravelling the Pattern: The Magus Figures in The Wheel of Time A significant plot or pattern element in contemporary high fantasy is the use of a range of superhuman characters (i.e. those of a higher nature or possessed of magical powers) who function as helpers to or opponents of the hero. For the purpose of my thesis I am defining the magus as a superhuman character, whether male or female, wh3 is given or progressively assumes a role of responsibility for keeping the pattern of mortal existence in balance, in order to save his or her world from destruction by the forces of the Dark. Although the trope of the magus has been much written about, as a kind of magical warrior, less attention has been paid to the role played by this figure in high fantasy as an interpreter of the discernible patterns of the heroic quest. It takes an extraordinary interpreter in the text to make sense of the pattern of destiny that forms around the central characters in works such as Robert Jordan's WOT. It is in the light of pattern interpreter and keeper, or of pattern disrupter, that I wish to explore the dualism of Ligh: and Dark that Jordan assigns to the stock figure of the magus, which continues to play such a pivotal element in the fantasy genre. Accordingly, this chapter provides an exposition of Jordan's patterning of Light and Dark in his presentation of three female magus figures. Moraine symbolises 'good' and rationality. She is dedicated to keeping Rand within the pattern that will bring victory for the forces of Light. -

The City & the City by China Mieville

The City & the City by China Mieville Inspector Tyador Borlu must travel to Ul Qoma to search for answers in the murder of a woman found in the city of Beszel. Why you'll like it: Thought-provoking. Gritty. Hard-boiled mystery. About the Author: China Miéville is the author of King Rat; Perdido Street Station, winner of the Arthur C. Clarke Award and the British Fantasy Award; The Scar, winner of the Locus Award and the British Fantasy Award; Iron Council, winner of the Locus Award and the Arthur C. Clarke Award; Looking for Jake, a collection of short stories; and Un Lun Dun, his New York Times bestselling book for younger readers. He lives and works in London. Questions for discussion 1. Mieville provides no overall exposition in this book, leaving it up to readers to piece together the strange co-existence of Beszel and Ul Qoma. Do you appreciate the way in which the story gradually unfolds? Or, finding it confusing, would you have preferred an explanation early on? 2. Many critics and readers—but not all—have talked about Mieville's imagined world, a world constructed so thoroughly that readers were easily absorbed in the two cities. Was that your experience as you read the book...or were you unable to suspend your belief, finding the whole foundation too preposterous? 3. What does it mean to "unsee" in this novel...and what are the symbolic implications of unseeing? In other words, do we "unsee" one another in our own lives? Who unsees whom? 4. Talk about the absurdities that result from the two cities ignoring one another's existence—for instance, the rules put in place for picking up street trash.