Chapter Two Unravelling the Pattern: the Magus Figures in the Wheel Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert Jordan's “The Wheel of Time” an Unofficial Worldbook for GURPS(Tm) by Aaron Sherman

Robert Jordan's “The Wheel of Time” an unofficial worldbook for GURPS(tm) by Aaron Sherman DRAFT: April 2018 This is an early draft of an unofficial worldbook for the Wheel of Time series. The goal is to provide everything that a commercial-class GURPS worldbook would provide: the magic system, advantages, disads, skills, templates, item and culture write-ups, creatures and ways to tie all of this into your game. If you want to contribute, drop me a line at [email protected]. Please note that this worldbook was originally published in 2000, and has only been lightly updated since. Information from later books and subsequent versions of the GURPS system have not been applied. Table of Contents Acknowledgements Introduction GURPS Magic Terms Aspects of the One Power Mechanics Opening Up Bad Things The Taint Sensing Magic Example Spells Disadvantages Advantages Skills Cultures, Groups and Races Aes Sedai Aiel Asha'man Atha'an Miere Caemlyn / Andor Ebu Dar / Altara Ogier Seanchan Tinkers/Traveling People Creatures gholam Gray Man Myrddraal Trollocs TODO Templates About Templates Aes Sedai Warder Wilder Asha'man Aiel Warrior Aiel Wise Woman Items Other Places tel'aran'rhiod Campaign Ideas Aes Sedai Borderlands Sub-plots The Age of Legends The Dark Side The Kin Asha'man Guidelines Changes Acknowledgements Credit where credit is due: The terms and quotes herein are taken from Robert Jordan (the Wheel of Time source material which comes from all 8 (so far) Wheel of Time books, published by Tor Fantasy) and Steve Jackson Games (the GURPS terms and references). The rest is Copyright 1998 by Aaron Sherman. -

Emergence of Kalacakratantra

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Apollo EMERGENCE OF KALACAKRATANTRA -B. Ghosh The characteristics of Tantra/ Agama/Yamala as in important Hindu works are present in the Buddhist Tantras. The Buddhist Tantras are found in three great divisions into which esoteric Buddhism is divided namely, Vajrayana, Sahajayana and Kalacakrayana. Besides these, three other minor yanas with no marked indlviduality, such as, Tantrayana, Mantrayana, Bhadrayana etc. (B. Bhattacharyya, Introduction to Buddhist Esoterism (COS) Varanasi, 1964, pp. 52-)5). The advanced Buddhist Tantras . are Kriyatantra, Caryatantra, Yogatantra and Anuttara tantra. It appears from the following citation from the Mulatantra that Kalacakrayana is the earliest source of all later Buddhist Tantric systems. Naropada/Naropa/ Narotapa flourished about 990 A.D. (B.Bhattacharyya, Sadhanamala Pt. m. In Sekoddesatika (Ed. Merrio E, Carelli, GOS, 1941) while narrating the manifestation of Bhagavan Sri Vajrapani Naropa quotes verses from the Mulatantra: At the outset it should be noted that "Kalacakra" is one of the epithets of Vajri : 19 The Sekoddesatika deaJs with the origin of Vajrayana giving a short account of the Jegend which was the sour<;,e of the doctrine. In Tantric Literature there are several systems, each of which is attributed to a different revela tion. Here it is said that the teachings of Mantrayana (Vajrayana) were given first by Dipankara, the Tathagata Buddha, preceding the historic one. But they had to be adopted to the later age and for the purpose the king Sucandr a, whose real m is loca ted by Sekoddesa in Shambala (bDe-hByung) on the north of river Sita. -

Time and the Tsunami

Helmreich, Stefan. 2006. Time and the Tsunami. In “Water: Resources & Discourses,” Justin M. Scott Coe and W. Scott Howard, eds., special issue of Reconstruction: Studies in Contemporary Culture 6(3): http://reconstruction.eserver.org/063/helmreich.shtml Reconstruction 6.3 (Summer 2006) Time and the Tsunami / Stefan Helmreich Abstract: In this article, Stefan Helmreich delivers an ethnographic report on an international academic conference of physical and biological oceanographers held in Goa, India, shortly after the Indian Ocean tsunami of December 26, 2004. Juxtaposing scientific discussions of the tsunami with novelist and anthropologist Amitav Ghosh's early 2005 visit to the hard-hit Andaman Islands, Helmreich examines various styles of narrating time in circulation in the wake of the disaster. Centering his attention on marine scientists, Helmreich discusses a tension between geological time and what he calls oscillating ocean time, a genre of time that takes in such long durée processes as ocean circulation as well as such rapid changes as tides and waves, which he argues are densely entwined with the turbulent temporality of human activity and sociality. <1> On January 4, 2005, marine scientists on board the Sagar Kanya, the flagship research vessel of India's National Institute of Oceanography, set out for the Andaman Islands to survey the damage wrought by the Indian Ocean tsunami of December 26, 2004. Embarking on a voyage quickly mandated by the Indian Department of Science and Technology on December 29, these researchers planned to assess the undersea movement of the Indian tectonic plate towards the Burma plate and to assay the geological and geographic transformations visited upon the landscape of the archipelago. -

The Sacred Mahakala in the Hindu and Buddhist Texts

Nepalese Culture Vol. XIII : 77-94, 2019 Central Department of NeHCA, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal The sacred Mahakala in the Hindu and Buddhist texts Dr. Poonam R L Rana Abstract Mahakala is the God of Time, Maya, Creation, Destruction and Power. He is affiliated with Lord Shiva. His abode is the cremation grounds and has four arms and three eyes, sitting on five corpse. He holds trident, drum, sword and hammer. He rubs ashes from the cremation ground. He is surrounded by vultures and jackals. His consort is Kali. Both together personify time and destructive powers. The paper deals with Sacred Mahakala and it mentions legends, tales, myths in Hindus and Buddhist texts. It includes various types, forms and iconographic features of Mahakalas. This research concludes that sacred Mahakala is of great significance to both the Buddhist and the Hindus alike. Key-words: Sacred Mahakala, Hindu texts, Buddhist texts. Mahakala Newari Pauwa Etymology of the name Mahakala The word Mahakala is a Sanskrit word . Maha means ‘Great’ and Kala refers to ‘ Time or Death’ . Mahakala means “ Beyond time or Death”(Mukherjee, (1988). NY). The Tibetan Buddhism calls ‘Mahakala’ NagpoChenpo’ meaning the ‘ Great Black One’ and also ‘Ganpo’ which means ‘The Protector’. The Iconographic features of Mahakala in Hindu text In the ShaktisamgamaTantra. The male spouse of Mahakali is the outwardly frightening Mahakala (Great Time), whose meditatative image (dhyana), mantra, yantra and meditation . In the Shaktisamgamatantra, the mantra of Mahakala is ‘Hum Hum Mahakalaprasidepraside Hrim Hrim Svaha.’ The meaning of the mantra is that Kalika, is the Virat, the bija of the mantra is Hum, the shakti is Hrim and the linchpin is Svaha. -

THE RISE of the NEW HYBORIAN LEGION, PART EIGHT by Lee A

REHeapa Vernal Equinox 2020 THE RISE OF THE NEW HYBORIAN LEGION, PART EIGHT By Lee A. Breakiron As we saw in our first installment [1], the Robert E. Howard United Press Association (REHupa) was founded in 1972 by a teen-aged Tim Marion as the first amateur press association (apa) devoted to Howard. Brian Earl Brown became Official Editor (OE) by 1977 and put in a lot of work guiding the organization, though not always competently. The Mailings at that time were in a real doldrums due to the paucity of REH-related content and the lack of any interest by Brown to do anything about it. In the early 1980s, Rusty Burke, Vernon Clark, and Graeme Flanagan started pushing for more Howard-related content, with Burke finally wresting away the editorship from Brown, as we saw last time. By mid-1984, the regular membership stood at only 23 and Mailings were down to about 130 pages in length. Post-Brown Mailings were not as big or as prompt as they had been, but were of higher quality in content and appearance, with some upswing in REH-related content and marked by more responsive and less contentious administration. L. Sprague de Camp, Glenn Lord, Karl Edward Wagner, and Everett Winne were honorary members, and copies were being archived at Ranger, Tex., Junior College. Former, longtime REHupan James Van Hise wrote the first comprehensive history of REHupa through Mailing #175. [2] Like him, but more so, we are focusing only on noteworthy content, especially that relevant to Howard. Here are the highlights of Mailings #71 through #80. -

In Partial Ful-Fiiimenl of the Requirements for the Degree of Naster of Arts in Department of Engl I Sh

BELLOW'S HENDERSON: ÀMERICANS ÀWAKE by Jian j iong Zhu À thes i s presented to the University of Manitoba in partial ful-fiIImenl of the requirements for the degree of naster of arts in Department of Engl i sh Winnipeg, Man i t oba (c) ;ianjiong zhu, 1987 Permission has been granted L'autorisation a ôté accordée to the National- Library of à ta Bibliothèque nationale Canada to microfilm this du Canada de microf i lmer thesis and to lend or se11 cette thèse eÈ de prêter ou copies of the film. de vendre des exempl_aires du fi lm. The author (copyright owner) L'auteur (titulaire du droit has reserved other d' auteur ) se rêserve les publication rìghts, and autres droits de publication; neither the thesis nor ni la thèse ni de longs extensive extracts from it extraits de cë11e-ci ne may be printed or otherwise doivent être imprimês ou reproduced without his/her autrement reproduits sans son wr j.tten permission. autorisation écrite. rsBN 0-315_37350_4 BELLOWT S HENDERSON: ATÍERICANS AWAKE BY JIANJIONG ZHU A thês¡s submined to thc Faculty of Gladuete Stud¡es of thc Univcrsity of Man¡toba ¡n pert¡al fulf¡flment of the rcquirrmcnts of the dcgrcc of I'IASTER OF ARTS @ t.987 Pcrmission has bccn grantcd to the L¡BRARY OF THE UNIVER- S¡TY OF MANTTOBA ro tcnd or sell copics of this rhesis, to the NATTONAL L¡BR.ARY OF CANADA ro microfitm this thcsis and to lcnd or æü copies of the film, and UNIVERSITY M¡CROF¡LMS to publish an ebsrrect of this thcsis. -

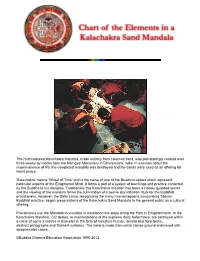

Chart of the Kalachakra Mandala.Pdf

The multicoloured Kalachakra Mandala, made entirely from coloured sand, was painstakingly created over three weeks by monks from the Namgyal Monastery in Dharamsala, India. In a lesson about the impermanence of life, the completed mandala was destroyed and the sands were used as an offering for world peace. 'Kalachakra' means 'Wheel of Time' and is the name of one of the Buddhist deities which represent particular aspects of the Enlightened Mind. It forms a part of a system of teachings and practice conferred by the Buddha to his disciples. Traditionally this Kalachakra Initiation has been a closely guarded secret and the viewing of the mandala forms the culmination of a twelve day initiation ritual for the Buddhist practitioners. However, the Dalai Lama, recognizing the many misconceptions surrounding Tibetan Buddhist practice, began presentations of the Kalachakra Sand Mandala to the general public as a cultural offering. Practitioners use the Mandala to visualize in meditation the steps along the Path to Enlightenment. In the Kalachakra Mandala, 722 deities, or manifestations of the supreme deity Kalachakra, are portrayed within a circle of some 2 metres in diameter in the form of miniature human, animal and flora forms, abstract pictographs and Sanskrit syllables. The sand is made from white stones ground and mixed with opaquewater colors. ©Buddha Dharma Education Association 1996-2012 1. Mandala of Great Bliss with a lotus flower center housing six deities including Kalachakra and Vishvamata, Askshobhya and Prajnaparamita, Vajrasattva and Vajradhatvishvari surrounded by eight shaktis 2. Mandala of Enlightened Wisdom 3. Mandala of Enlightened Mind 4. Mandala of Enlightened Speech 5. -

Three Readings of the Eternal Return Michael James Maclaggan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2014 Three Readings of the Eternal Return Michael James MacLaggan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation MacLaggan, Michael James, "Three Readings of the Eternal Return" (2014). LSU Master's Theses. 861. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/861 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THREE READINGS OF THE ETERNAL RETURN A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies by Michael James MacLaggan B.S., University of Texas at Austin, 2004 August 2014 To the greatest of them all: Sanford L. “Sandy” Bauman, ordinary philosopher. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................................................................................... iv INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................................ -

![The Nemedian Chroniclers #29 [WS19]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8591/the-nemedian-chroniclers-29-ws19-2448591.webp)

The Nemedian Chroniclers #29 [WS19]

REHeapa Winter Solstice 2019 THE RISE OF THE NEW HYBORIAN LEGION, PART SEVEN By Lee A. Breakiron As we saw in our first installment [1], the Robert E. Howard United Press Association (REHupa) was founded in 1972 by a teen-aged Tim Marion as the first amateur press association (apa) devoted to Howard. Brian Earl Brown became Official Editor (OE) by 1977 and put in a lot of work guiding the organization, though not always competently. The Mailings at that time were in a real doldrums due to the paucity of REH-related content and the lack of any interest by Brown to do anything about it, even to the point of his weakening the rules that used to require such content. He at least had good communications with members, explaining problems and actions, and holding votes over issues. In the early 1980s, Rusty Burke, Vernon Clark, and Graeme Flanagan started pushing for more Howard-related content, with Burke finally wresting away the editorship from Brown, as we shall see. By 1983, the regular membership stood at only 22 and Mailings were running about 190 pages in length, though the 10th anniversary issue #60 did peak at 478. L. Sprague de Camp, Glenn Lord, and Karl Edward Wagner were honorary members, and copies were being archived at Ranger, Tex., Junior College. Former, longtime REHupan James Van Hise wrote the first comprehensive history of REHupa through Mailing #175. [2] Like him, but more so, we are focusing only on noteworthy content, especially that relevant to Howard. Here are the highlights of Mailings #61 through #70. -

Preface: the Myth of the Eternal Return

Founder and Editor-in-Chief Ananta Ch. Sukla Vishvanatha Kaviraja Institute A 42, Sector-7, Markat Nagar Cuttack, Odisha, India : 753014 Email: [email protected] Tel: 91-0671-2361010 Editor Associate Editor Asunción López-Varela Richard Shusterman Faculty of Philology Center for Body, Mind and Culture University of Complutense Florida Atlantic University Madrid 28040, 777 Glades Road, Boca Raton Spain Florida - 33431-0991, U.S.A. Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Editorial Board W.J.T. Mitchel University of Chicago David Damrosch Harvard University Alexander Huang Massachusetts Institue of Technology Garry Hagberg Bard College John Hyman Qeen’s College, Oxford Meir Sternberg Tel Aviv University Grazia Marchiano University of Siena David Fenner University of North Florida Roger Ames University of Hawaii George E. Rowe University of Oregon Sushil K. Saxena University of Delhi Susan Feagin Temple University Peter Lamarque University of York Brigitte Le Luez Dublin City University Deborah Weagel University of New Mexico John MacKinnon University of Saint Mary Osayimwense Osa Virginia State University All editorial communications, subscriptions, books for review/ notes, papers for publication are to be mailed to the editor at the address mentioned above. Editorial Assistants : Bishnu Dash ([email protected]) : Sanjaya Sarangi ([email protected]) Technical Assistant : Bijay Mohanty ([email protected]) JOURNAL OF COMPARATIVE LITERATURE AND AESTHETICS Volume : 40.2 : 2017 Journal of Comparative Literature and Aesthetics A Special Issue in The Eternal Return of Myth: Myth updating in Contemporary Literature Guest - Editors Ana González-Rivas Fernández & Antonella Lipscomb A VISHVANATHA KAVIRAJA INSTITUTE PUBLICATION www.jclaonline.org http://www.ucm.es/siim/journal-of-comparative-literature-and-aesthetics ISSN: 0252-8169 CONTENTS Felicitations on the 75th Birthday of the Founding Editor Prof. -

Master´S Thesis Project Cover Page for the Master's Thesis

The Faculty of Humanities Master´s Thesis Project Cover page for the Master’s thesis Submission January: [year] June: 2020 Other: [Date and year] Supervisor: Bryan Yazell Department: HUM Title, Danish: Title, English: On Magic: How Magic Systems in Modern Fantasy Disrupt Power Structures of Race, Class, and Gender Min./Max. number of characters: 144,000 – 192,000 Number of characters in assignment1: (60 – 80 normal pages) 169,570 (1 norm page = 2400 characters incl. blank spaces) Please notice that in case your Master’s thesis project does not meet the minimum/maximum requirements stipulated in the curriculum your assignment will be dismissed and you will have used up one examination attempt. (Please The Master’s thesis may in anonymized form be used for teaching/guidance of mark) future thesis students __X__ Solemn declaration I hereby declare that I have drawn up the assignment single-handed and independently. All quotes are marked as such and duly referenced. The full assignment or parts thereof have not been handed in as full or partial fulfilment of examination requirements in any other courses. Read more here: http://www.sdu.dk/en/Information_til/Studerende_ved_SDU/Eksamen.aspx Handed in by: First name: Helen Last name: Jones Date of birth: 02/02/1996 1 Characters are counted from the first character in the introduction until and including the last character in the conclusion. Footnotes are included. Charts are counted with theirs characters. The following is excluded from the total count: abstract, table of contents, bibliography, list of references, appendix. For more information, see the examination regulations of the course in the curriculum. -

Conan the Victorious by Robert Jordan

Read and Download Ebook Conan the Victorious... Conan the Victorious Robert Jordan PDF File: Conan the Victorious... 1 Read and Download Ebook Conan the Victorious... Conan the Victorious Robert Jordan Conan the Victorious Robert Jordan In the fabled, mysterious land of Vendhya, Conan seeks an antidote to the unknown poison that threatens his life. Entangled in the intrigues of Karim Singh, advisor to the King of Vendhya, pursued by the voluptuous noblewoman Vyndra, threatened by the evil mage Naipal, Conan has yet to conquer the most terrifying adversaries of his life--the Sivani, demon-guardians of the ancient tombs of Vendhyan kings. To survive, he must be Conan the Victorious. Conan the Victorious Details Date : Published March 15th 1991 by Tor Books (first published 1984) ISBN : 9780812513998 Author : Robert Jordan Format : Paperback 288 pages Genre : Fantasy, Heroic Fantasy, Sword and Sorcery, Fiction, Science Fiction Fantasy Download Conan the Victorious ...pdf Read Online Conan the Victorious ...pdf Download and Read Free Online Conan the Victorious Robert Jordan PDF File: Conan the Victorious... 2 Read and Download Ebook Conan the Victorious... From Reader Review Conan the Victorious for online ebook Charles says pastiche Georgene says One of the better Conan novels. Matthew says I enjoyed this Conan but, it was not my favorite. To me there was one to many things going on at once with different characters. There was quite a bit of action like all Conan books I've read with a bit of sorcery and evil plots. I still look forward to reading more Conan just this one to me falls a bit short in epicness.