Exploring Trauma Through Fantasy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writing the High Fantasy Film Ryan Mccue

Writing the High Fantasy Film Ryan McCue Faculty Mentor: Dr. Kelly Younger Loyola Marymount University Abstract: As the fantasy genre reaches ever greater heights in Hollywood, the high fantasy film continues to struggle. This research explores one of the most challenging subgenres in film, and puts forward fairy tales as one possible means of revitalizing it. I begin by exploring what constitutes a fantasy film as well as the recent history of fantasy in Hollywood. Then, I consider the merit of the high fantasy film as both escapism and as a means of dealing with social trauma. Finally, I consider how fairy tales—with their timeless and wide appeal—may assist filmmakers in writing more effective high fantasy films. By analyzing a selection of high fantasy films on the basis of how well they fit fairy-tale paradigms, I expect to find that the films which fall more in line with fairy-tale conventions also achieved greater success, whether that is critically, commercially, or in lasting cultural impact. Finally, I propose utilizing the results of the research to write my own original high fantasy film. McCue 2 Narrative Introduction: Currently, it can be said that Hollywood is an empire of fantasy. Year-to-year the most successful films—whether that be a superhero movie or a new Pixar film—are those that weave fantastical elements into their narratives (Box Office Mojo). Yet despite the recent success fantasy has found in Hollywood, there is a certain type of fantasy film that continues to struggle: the high fantasy film. While high fantasy has found success in animation and television, in the realm of live-action film these stories have become incredibly rare. -

Fantasy and Imagination: Discovering the Threshold of Meaning David Michael Westlake

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 5-2005 Fantasy and Imagination: Discovering the Threshold of Meaning David Michael Westlake Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Westlake, David Michael, "Fantasy and Imagination: Discovering the Threshold of Meaning" (2005). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 477. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/477 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. FANTASY AND IMAGINATION: DISCOVERING THE THRESHOLD OF MEANING BY David Michael Westlake B.A. University of Maine, 1997 A MASTER PROJECT Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in Liberal Studies) The Graduate School The University of Maine May, 2005 Advisory Committee: Kristina Passman, Associate Professor of Classical Language and Literature, Advisor Jay Bregrnan, Professor of History Nancy Ogle, Professor of Music FANTASY AND IMAGINATION: DISCOVERING THE THRESHOLD OF MEANING By David Michael Westlake Thesis Advisor: Dr. Kristina Passman An Abstract of the Master Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in Liberal Studies) May, 2005 This thesis addresses the ultimate question of western humanity; how does one find meaning in the present era? It offers the reader one powerful way for this to happen, and that is through the stories found in the pages of Fantasy literature. It begins with Frederick Nietzsche's declaration that, "God is dead." This describes the situation of men and women in his time and today. -

36TH CAIRO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL PROGRAMME November (9-18)

36TH CAIRO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL PROGRAMME November (9-18) • No children are allowed. • Unified prices for all tickets: 20 EGP. • 50% discount for students of universities, technical institutes, and members of artistic syndicates, film associations and writers union. • Booking will open on Saturday, November 8, 2014 from 9am- 10pm. • Doors open 15 minutes prior to screenings • Doors close by the start of the screenings • No mobiles or cameras are allowed inside the screening halls. 1 VENUES OF THE FESTIVAL Main Hall – Cairo Opera House 1000 seats - International Competition - Special Presentations - Festival of Festivals (Badges – Tickets) Small Hall – Cairo Opera House 340 seats - Prospects of Arab Cinema (Badges – Tickets) - Films on Films (Badges) El Hanager Theatre - El Hanager Arts Center 230 seats - Special Presentations - Festival of Festivals (Badges – Tickets) El El Hanager Cinema - El Hanager Arts Center 120 seats - International Cinema of Tomorrow - Short films Competition - Student Films Competition - Short Film classics - Special Presentations - Festival of festivals (Badges) Creativity Cinema - Artistic Creativity Center 200 seats - International Critic’s Week - Feature Film Classics (Badges) El Hadara 1 75 seats - The Greek Cinema guest of honor (Badges) 2 El Hadara 2 75 seats - Reruns of the Main Hall Screenings El Hanager Foyer- El Hanager Arts Center - Gallery of Cinematic Prints Exhibition Hall- El Hanager Arts Center - Exhibition of the 100th birth anniversary of Barakat El- Bab Gallery- Museum of Modern Art - -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Lost Pigs and Broken Genes: The search for causes of embryonic loss in the pig and the assembly of a more contiguous reference genome Amanda Warr A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh 2019 Division of Genetics and Genomics, The Roslin Institute and Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, University of Edinburgh Declaration I declare that the work contained in this thesis has been carried out, and the thesis composed, by the candidate Amanda Warr. Contributions by other individuals have been indicated throughout the thesis. These include contributions from other authors and influences of peer reviewers on manuscripts as part of the first chapter, the second chapter, and the fifth chapter. Parts of the wet lab methods including DNA extractions and Illumina sequencing were carried out by, or assistance was provided by, other researchers and this too has been indicated throughout the thesis. -

Dont Want to Miss a Thing PDF Book

DONT WANT TO MISS A THING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jill Mansell | 432 pages | 20 Jun 2013 | Headline Publishing Group | 9780755355891 | English | London, United Kingdom Dont Want to Miss a Thing PDF Book IFPI Austria. Share This:. Sunday 12 July Goodreads user They are all hilarious in their own way. France SNEP [18]. The song also stayed at number one for several weeks in several other countries, including Australia, Ireland and Norway. I think this is probably the best Jill Mansell I've thus fa I don't read chick-lit, of course I wouldn't I liked how solid that turned out. Frankie took it too well besides throwing Joe out. His sister, Laura has passed away, and suddenly, baby Delphi needs a carer. Sort order. Road Runner. Toys in the Attic Fever 6. A new version of Last. I really hope her next book will bring something fresh to the table, I'm getting rather bored by her predictable storylines. I feel like this review is getting random but this book was so random. Enlarge cover. But one thing still eluded them. The other part that bothered me was the book making offence to transgender people. That was welcomed by the band. France SNEP [47]. We'll assume you're ok with this, but you can opt-out if you wish. Check it out from the library or something. US Adult Contemporary Billboard [33]. This is a thoroughly satisfying emotional read and I loved every word. I feel it would have been more appropriate for Amber to still not talk to her father for more time even if she was going through a rebellious phase or not. -

Recovering the Palestinian History of Dispossession Through Graphics in Leila Abdelrazaq’S Baddawi

MONOGRAPHIC Eikón Imago e-ISSN: 2254-8718 Recovering the Palestinian History of Dispossession through Graphics in Leila Abdelrazaq’s Baddawi Arya Priyadarshini1; Suman Sigroha2 Recibido: 15 de mayo de 2020 / Aceptado: 10 de junio de 2020 / Publicado: 3 de julio de 2020 Abstract. Documentation is a significant mechanism to prove one’s identity. Palestinians, being robbed of this privilege to document their history, have taken upon other creative means to prove their existence. Being instruments of resistance, graphics and comics have a historical prominence in the Palestinian community. Building on this rich history of resistance through art, the paper contends that the modern graphic novel is used as a tool by the author to reclaim the Palestinian identity by drawing their rootedness in the region, thus resisting their effacement from public memory. Keywords: Graphic Novel; Resistance; Trauma; Memory; Intifada; Displacement; Baddawi. [es] Recuperando la historia palestina de desposesión a través de gráficos en Baddawi de Leila Abdelrazaq Resumen. La documentación es un mecanismo significativo para probar la identidad de uno. Los palestinos, al ser despojados de este privilegio de documentar su historia, han tomado otros medios creativos para demostrar su existencia. Al ser instrumentos de resistencia, los gráficos y los cómics tienen una importancia histórica en la comunidad palestina. Sobre la base de esta rica historia de resistencia a través del arte, el artículo sostiene que la novela gráfica moderna, que es en sí misma un producto de resistencia a los cómics convencionales, es utilizada por el autor como una herramienta para recuperar la identidad palestina al extraer su arraigo en la región, resistiendo así la narrativa dominante y su borrado de la historia. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Chapter 3 Heroines in a Time of War: Nelvana of the Northern Lights And

Chapter 3 Heroines in a Time of War: Nelvana of the Northern Lights and Wonder Woman as Symbols of the United States and Canada Scores of superheroes emerged in comic books just in time to defend the United States and Canada from the evil machinations of super-villains, Hitler, Mussolini, and other World War II era enemies. By 1941, War Nurse Pat Parker, Miss America, Pat Patriot, and Miss Victory were but a few of the patriotic female characters who had appeared in comics to fight villains and promote the war effort. These characters had all but disappeared by 1946, a testament to their limited wartime relevance. Though Nelvana of the Northern Lights (hereafter “Nelvana”) and Wonder Woman first appeared alongside the others in 1941, they have proven to be more enduring superheroes than their crime-fighting colleagues. In particular, Nelvana was one of five comic book characters depicted in the 1995 Canada Post Comic Book Stamp Collection, and Wonder Woman was one of ten DC Comics superheroes featured in the 2006 United States Postal Service (USPS) Commemorative Stamp Series. The uniquely enduring iconic statuses of Nelvana and Wonder Woman result from their adventures and character development in the context of World War II and the political, social, and cultural climates in their respective English-speaking areas of North America. Through a comparative analysis of Wonder Woman and Nelvana, two of their 1942 adventures, and their subsequent deployment through government-issued postage stamps, I will demonstrate how the two characters embody and reinforce what Michael Billig terms “banal nationalism” in their respective national contexts. -

Children's Fairy Tales Science Fiction and Fantasy

Children's Fairy Tales Science Fiction and Fantasy *Multiple Children's Fairy Tales, Science Fiction and Fantasy Locations Author Title Call # Abbott, Tony Secrets of Droon (Series) JF Adler, Carole S. Eddie’s Blue-Wing Dragon JF Alcock, Vivien The Monster Garden JF Alexander, Lloyd The First Two Lives of Lucas Kasha JF Alexander, Lloyd Prydain Chronicles (Series) JF* Alexander, Lloyd Vesper Holly Adventure (Series) JF Alexander, Lloyd Westmark Trilogy (Series) JF* Applegate, K.A. Animorphs (Series) JF Applegate, K.A. Animorphs Megamorphs (Series) JF Arnold, Louise Golden and Grey (an Unremarkable Boy and a RatherJF Remarkable Ghost) Austin, R.G. Famous and Rich JF Avi Crispin (Series) YA Avi Midnight Magic JF Avi No More Magic JMyst Avi Perloo the Bold JF* Avi Something Upstairs : A Tale of Ghosts YA Avi Windcatcher JF Babbitt, Natalie The Devil’s Other Storybook JF Babbitt, Natalie Tuck Everlasting JF* Banks, Lynne Reid The Fairy Rebel JF Banks, Lynne Reid The Indian in the Cupboard (books) JF* Banks, Lynne Reid The Magic Hare JF Barrie, James M. Peter Pan JF* Baum, L. Frank The Wizard of Oz (Series) JF* Beachcroft, Nina The Wishing People JF Bechard, Margaret Star Hatchling JF Bellairs, John Johnny Dixon Mystery (Series) JMyst Bellairs, John The House With a Clock in It’s Walls JMyst *Multiple Children's Fairy Tales, Science Fiction and Fantasy Locations Author Title Call # Bellairs, John Anthony Monday Mystery (Series) JMyst Billingsley, Fanny The Folk Keeper JF Billingsley, Franny Well Wished JF Blade, Adam Beast Quest (Series) JF Brittain, Bill Devil’s Donkey JF Brittain, Bill Dr. -

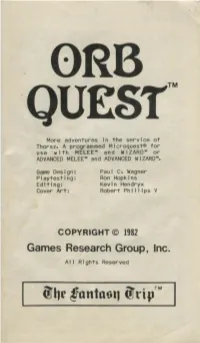

ORB QUEST™ Is a Programmed Adventure for the Instruction, It W I 11 Give You Information and FANTASY TRIP™ Game System

0RB QUEST™ More adventures in the service of Thorsz. A programmed Microquest® for use with ME LEE'" and WIZARD'" or ADVANCED MELEE'" and ADVANCED WIZARD'". Game Design: Paul c. Wagner Playtesting: Ron Hopkins Editing: Kevin Hendryx Cover Art: Robert Phillips V COPYRIGHT© 1982 Games Research Group, Inc. Al I Rights Reserved 3 2 from agai~ Enough prospered, however, to establish INTRODUCTION the base of the kingdom and dynasty of the Thorsz as it now stands. During evening rounds outside the w i. zard's "With time and the excess of luxuries brought quarters at the Thorsz's pa I ace, you are. deta 1 n~~ b~ about by these successes, the fate of the ear I i er a red-robed figure who speaks to you 1 n a su ue orbs was forgotten. Too many were content with tone. "There is a task that needs to _be done," their lot and power of the present and did not look murmurs the mage, "which is I~ the service of the forward into the future. And now, disturbing news Thorsz. It is fu I I of hardsh 1 ps and d~ngers, but Indeed has deve I oped. your rewards and renown w i I I be accord 1 ng I Y great. "The I and surrounding the rea I ms of the Thorsz Wi II you accept this bidding?" has become darker, more foreboding, and more With a silent nod you agree. dangerous. One in five patrols of the border guard "Good," mutters the wizard. "Here 1 s a to~en to returns with injury, or not at al I. -

Toward a Theory of the Dark Fantastic: the Role of Racial Difference in Young Adult Speculative Fiction and Media

Journal of Language and Literacy Education Vol. 14 Issue 1—Spring 2018 Toward a Theory of the Dark Fantastic: The Role of Racial Difference in Young Adult Speculative Fiction and Media Ebony Elizabeth Thomas Abstract: Humans read and listen to stories not only to be informed but also as a way to enter worlds that are not like our own. Stories provide mirrors, windows, and doors into other existences, both real and imagined. A sense of the infinite possibilities inherent in fairy tales, fantasy, science fiction, comics, and graphic novels draws children, teens, and adults from all backgrounds to speculative fiction – also known as the fantastic. However, when people of color seek passageways into &the fantastic, we often discover that the doors are barred. Even the very act of dreaming of worlds-that-never-were can be challenging when the known world does not provide many liberatory spaces. The dark fantastic cycle posits that the presence of Black characters in mainstream speculative fiction creates a dilemma. The way that this dilemma is most often resolved is by enacting violence against the character, who then haunts the narrative. This is what readers of the fantastic expect, for it mirrors the spectacle of symbolic violence against the Dark Other in our own world. Moving through spectacle, hesitation, violence, and haunting, the dark fantastic cycle is only interrupted through emancipation – transforming objectified Dark Others into agentive Dark Ones. Yet the success of new narratives fromBlack Panther in the Marvel Cinematic universe, the recent Hugo Awards won by N.K. Jemisin and Nnedi Okorafor, and the blossoming of Afrofuturistic and Black fantastic tales prove that all people need new mythologies – new “stories about stories.” In addition to amplifying diverse fantasy, liberating the rest of the fantastic from its fear and loathing of darkness and Dark Others is essential. -

Redirected from Films Considered the Greatest Ever) Page Semi-Protected This List Needs Additional Citations for Verification

List of films considered the best From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Films considered the greatest ever) Page semi-protected This list needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be chall enged and removed. (November 2008) While there is no general agreement upon the greatest film, many publications an d organizations have tried to determine the films considered the best. Each film listed here has been mentioned in a notable survey, whether a popular poll, or a poll among film reviewers. Many of these sources focus on American films or we re polls of English-speaking film-goers, but those considered the greatest withi n their respective countries are also included here. Many films are widely consi dered among the best ever made, whether they appear at number one on each list o r not. For example, many believe that Orson Welles' Citizen Kane is the best mov ie ever made, and it appears as #1 on AFI's Best Movies list, whereas The Shawsh ank Redemption is #1 on the IMDB Top 250, whilst Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back is #1 on the Empire magazine's Top 301 List. None of the surveys that produced these citations should be viewed as a scientif ic measure of the film-watching world. Each may suffer the effects of vote stack ing or skewed demographics. Internet-based surveys have a self-selected audience of unknown participants. The methodology of some surveys may be questionable. S ometimes (as in the case of the American Film Institute) voters were asked to se lect films from a limited list of entries.