Harry Potter As High Fantasy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: a Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-7-2012 Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant James H. Shimkus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Shimkus, James H., "Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING SPECULATIVE FICTION IN COLLEGE: A PEDAGOGY FOR MAKING ENGLISH STUDIES RELEVANT by JAMES HAMMOND SHIMKUS Under the Direction of Dr. Elizabeth Burmester ABSTRACT Speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) has steadily gained popularity both in culture and as a subject for study in college. While many helpful resources on teaching a particular genre or teaching particular texts within a genre exist, college teachers who have not previously taught science fiction, fantasy, or horror will benefit from a broader pedagogical overview of speculative fiction, and that is what this resource provides. Teachers who have previously taught speculative fiction may also benefit from the selection of alternative texts presented here. This resource includes an argument for the consideration of more speculative fiction in college English classes, whether in composition, literature, or creative writing, as well as overviews of the main theoretical discussions and definitions of each genre. -

Tolkien's Women: the Medieval Modern in the Lord of the Rings

Tolkien’s Women: The Medieval Modern in The Lord of the Rings Jon Michael Darga Tolkien’s Women: The Medieval Modern in The Lord of the Rings by Jon Michael Darga A thesis presented for the B.A. degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Winter 2014 © 2014 Jon Michael Darga For my cohort, for the support and for the laughter Acknowledgements My thanks go, first and foremost, to my advisor Andrea Zemgulys. She took a risk agreeing to work with a student she had never met on a book she had no academic experience in, and in doing so she gave me the opportunity of my undergraduate career. Andrea knew exactly when to provide her input and when it was best to prod and encourage me and then step out of the way; yet she was always there if I needed her, and every book that she recommended opened up a significant new argument that changed my thesis for the better. The independence and guidance she gave me has resulted in a project I am so, so proud of, and so grateful to her for. I feel so lucky to have had an advisor who could make me laugh while telling me how badly my thesis needed work, who didn’t judge me when I came to her sleep-deprived or couldn’t express myself, and who shared my passion through her willingness to join and guide me on this ride. Her constant encouragement kept me going. I also owe a distinct debt of gratitude to Gillian White, who led my cohort during the fall semester. -

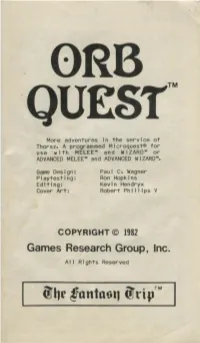

ORB QUEST™ Is a Programmed Adventure for the Instruction, It W I 11 Give You Information and FANTASY TRIP™ Game System

0RB QUEST™ More adventures in the service of Thorsz. A programmed Microquest® for use with ME LEE'" and WIZARD'" or ADVANCED MELEE'" and ADVANCED WIZARD'". Game Design: Paul c. Wagner Playtesting: Ron Hopkins Editing: Kevin Hendryx Cover Art: Robert Phillips V COPYRIGHT© 1982 Games Research Group, Inc. Al I Rights Reserved 3 2 from agai~ Enough prospered, however, to establish INTRODUCTION the base of the kingdom and dynasty of the Thorsz as it now stands. During evening rounds outside the w i. zard's "With time and the excess of luxuries brought quarters at the Thorsz's pa I ace, you are. deta 1 n~~ b~ about by these successes, the fate of the ear I i er a red-robed figure who speaks to you 1 n a su ue orbs was forgotten. Too many were content with tone. "There is a task that needs to _be done," their lot and power of the present and did not look murmurs the mage, "which is I~ the service of the forward into the future. And now, disturbing news Thorsz. It is fu I I of hardsh 1 ps and d~ngers, but Indeed has deve I oped. your rewards and renown w i I I be accord 1 ng I Y great. "The I and surrounding the rea I ms of the Thorsz Wi II you accept this bidding?" has become darker, more foreboding, and more With a silent nod you agree. dangerous. One in five patrols of the border guard "Good," mutters the wizard. "Here 1 s a to~en to returns with injury, or not at al I. -

Toward a Theory of the Dark Fantastic: the Role of Racial Difference in Young Adult Speculative Fiction and Media

Journal of Language and Literacy Education Vol. 14 Issue 1—Spring 2018 Toward a Theory of the Dark Fantastic: The Role of Racial Difference in Young Adult Speculative Fiction and Media Ebony Elizabeth Thomas Abstract: Humans read and listen to stories not only to be informed but also as a way to enter worlds that are not like our own. Stories provide mirrors, windows, and doors into other existences, both real and imagined. A sense of the infinite possibilities inherent in fairy tales, fantasy, science fiction, comics, and graphic novels draws children, teens, and adults from all backgrounds to speculative fiction – also known as the fantastic. However, when people of color seek passageways into &the fantastic, we often discover that the doors are barred. Even the very act of dreaming of worlds-that-never-were can be challenging when the known world does not provide many liberatory spaces. The dark fantastic cycle posits that the presence of Black characters in mainstream speculative fiction creates a dilemma. The way that this dilemma is most often resolved is by enacting violence against the character, who then haunts the narrative. This is what readers of the fantastic expect, for it mirrors the spectacle of symbolic violence against the Dark Other in our own world. Moving through spectacle, hesitation, violence, and haunting, the dark fantastic cycle is only interrupted through emancipation – transforming objectified Dark Others into agentive Dark Ones. Yet the success of new narratives fromBlack Panther in the Marvel Cinematic universe, the recent Hugo Awards won by N.K. Jemisin and Nnedi Okorafor, and the blossoming of Afrofuturistic and Black fantastic tales prove that all people need new mythologies – new “stories about stories.” In addition to amplifying diverse fantasy, liberating the rest of the fantastic from its fear and loathing of darkness and Dark Others is essential. -

Dragon Con Progress Report 2021 | Published by Dragon Con All Material, Unless Otherwise Noted, Is © 2021 Dragon Con, Inc

WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG INSIDE SEPT. 2 - 6, 2021 • ATLANTA, GEORGIA • WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG Announcements .......................................................................... 2 Guests ................................................................................... 4 Featured Guests .......................................................................... 4 4 FEATURED GUESTS Places to go, things to do, and Attending Pros ......................................................................... 26 people to see! Vendors ....................................................................................... 28 Special 35th Anniversary Insert .......................................... 31 Fan Tracks .................................................................................. 36 Special Events & Contests ............................................... 46 36 FAN TRACKS Art Show ................................................................................... 46 Choose your own adventure with one (or all) of our fan-run tracks. Blood Drive ................................................................................47 Comic & Pop Artist Alley ....................................................... 47 Friday Night Costume Contest ........................................... 48 Hallway Costume Contest .................................................. 48 Puppet Slam ............................................................................ 48 46 SPECIAL EVENTS Moments you won’t want to miss Masquerade Costume Contest ........................................ -

Mini-Episode 14: High Fantasy

Not Your Mother’s Library Transcript Mini-Episode 14: High Fantasy (Brief intro music) Rachel: Hello, and welcome to Not Your Mother’s Library, a readers’ advisory podcast from the Oak Creek Public Library. I’m Rachel, and you might be familiar with my voice by now because both Leah and I have been recording a whole bunch of mini-episodes while the library is closed due to the Coronavirus pandemic. Ya know, I played that board game once. “Pandemic,” I mean. I thought it was too complex, but that’s coming from someone who periodically forgets the rules of “Yahtzee.” Anyway, yes, at time of recording Oak Creek Public Library is closed, and staff like myself are offering virtual services in lieu of in- person interactions. Practice social distancing with us, and stay safe out there, everyone. Or, preferably, stay safe in there. Like, indoors. At home. You can catch up on being a couch potato by listening to podcasts, or take us with you while you go for a jog around the neighborhood. New media is versatile like that, and exercise is important. Technically. But, back on track. Leah and I are sharing some of our favorite books, movies, and other schtuff [sic]. Since this episode and the few that follow will be going out in May 2020, I thought I’d go with a new format just for the month. Let’s look into specific genres. This episode, as you can see from the title, we’ll explore high fantasy, and I plan to touch on other genres like horror and comedy and…niche…in future eps. -

FLM201 Film Genre: Understanding Types of Film (Study Guide)

Course Development Team Head of Programme : Khoo Sim Eng Course Developer(s) : Khoo Sim Eng Technical Writer : Maybel Heng, ETP © 2021 Singapore University of Social Sciences. All rights reserved. No part of this material may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Educational Technology & Production, Singapore University of Social Sciences. ISBN 978-981-47-6093-5 Educational Technology & Production Singapore University of Social Sciences 463 Clementi Road Singapore 599494 How to cite this Study Guide (MLA): Khoo, Sim Eng. FLM201 Film Genre: Understanding Types of Film (Study Guide). Singapore University of Social Sciences, 2021. Release V1.8 Build S1.0.5, T1.5.21 Table of Contents Table of Contents Course Guide 1. Welcome.................................................................................................................. CG-2 2. Course Description and Aims............................................................................ CG-3 3. Learning Outcomes.............................................................................................. CG-6 4. Learning Material................................................................................................. CG-7 5. Assessment Overview.......................................................................................... CG-8 6. Course Schedule.................................................................................................. CG-10 7. Learning Mode................................................................................................... -

Leadership Role Models in Fairy Tales-Using the Example of Folk Art

Review of European Studies; Vol. 5, No. 5; 2013 ISSN 1918-7173 E-ISSN 1918-7181 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Leadership Role Models in Fairy Tales - Using the Example of Folk Art and Fairy Tales, and Novels Especially in Cross-Cultural Comparison: German, Russian and Romanian Fairy Tales Maria Bostenaru Dan1, 2& Michael Kauffmann3 1 Urban and Landscape Design Department, “Ion Mincu” University of Architecture and Urbanism, Bucharest, Romania 2 Marie Curie Fellows Association, Brussels, Belgium 3 Formerly Graduate Research Network “Natural Disasters”, University of Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe, Germany Correspondence: Maria Bostenaru Dan, Urban and Landscape Design Department, “Ion Mincu” University of Architecture and Urbanism, Bucharest 010014, Romania. Tel: 40-21-3077-180. E-mail: [email protected] Received: August 11, 2013 Accepted: September 20, 2013 Online Published: October 11, 2013 doi:10.5539/res.v5n5p59 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/res.v5n5p59 Abstract In search of role models for leadership, this article deals with leadership figures in fairy tales. The focus is on leadership and female domination pictures. Just as the role of kings and princes, the role of their female hero is defined. There are strong and weak women, but by a special interest in the contribution is the development of the last of the first to power versus strength. Leadership means to deal with one's own person, 'self-rule, then, of rulers'. In fairy tales, we find different styles of leadership and management tools. As properties of the good boss is praised in particular the decision-making and less the organizational skills. -

Gatehouse Gazette ISSUE 9 NOV ‘09 ISSN 1879-5676

Gatehouse Gazette ISSUE 9 NOV ‘09 ISSN 1879-5676 BEAUtIFUl Industry EMRE TURHAL ISSUE 8 Gatehouse Gazette SEP ‘09 CONTENTS The Gatehouse Gazette is an FEATURES online magazine in publication Loving the Factory, too 3 since July 2008, dedicated to the Industry and machines in steampunk and dieselpunk. speculative fiction genres of 4 steampunk and dieselpunk. Alchemy for Mystery Interview with Carol McCleary, author of The Alchemy of Murder The Flying Scotsman 8 Not a man with wings but a champion of the steam railway. Start up the Big Machines 16 The industrialization of Britain, Germany and France compared. The Asylum 19 Thoughts on the recent Lincoln, England steampunk convivial. COLUMNS REVIEWS Dieselpunk Season 12 Hilde Heyvaert’s The Steampunk Wardrobe . The Alchemy The Martini 15 of Murder 4 Craig B. Daniel’s The Liquor Cabinet . Boilerplate 7 Quatermass and the Pit 11 Guy Dampier’s last Quatermass review. Leviathan 10 Dieselpunk Online 6 The Invisible An overview of what’s new at the premier dieselpunk websites. Frontier 13 Casshern 18 ©2009 Gatehouse Gazette . All rights reserved. Neither this publication nor any part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Gatehouse Gazette . Published every two months by The Gatehouse . Contact the editor at [email protected]. PAGE 2 ISSUE 8 Gatehouse Gazette SEP ‘09 EDITORIAL LOVING THE NICK OTTENS FACTORY, TOO THERE ARE STARK AND UNDENIABLE DIFFERENCES dieselpunk, more distinctly informed b y cyberpunk between the mindsets of steampunk and dieselpunk in sensibilities, is more likely to become a dystopia than its spite of the close bonds between both genres and those steampunk counterpart. -

Golden Fantasy: an Examination of Generic & Literary Fantasy in Popular Writing Zechariah James Morrison Seattle Pacific Nu Iversity

Seattle aP cific nivU ersity Digital Commons @ SPU Honors Projects University Scholars Spring June 3rd, 2016 Golden Fantasy: An Examination of Generic & Literary Fantasy in Popular Writing Zechariah James Morrison Seattle Pacific nU iversity Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/honorsprojects Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Morrison, Zechariah James, "Golden Fantasy: An Examination of Generic & Literary Fantasy in Popular Writing" (2016). Honors Projects. 50. https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/honorsprojects/50 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the University Scholars at Digital Commons @ SPU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ SPU. Golden Fantasy By Zechariah James Morrison Faculty Advisor, Owen Ewald Second Reader, Doug Thorpe A project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University Scholars Program Seattle Pacific University 2016 2 Walk into any bookstore and you can easily find a section with the title “Fantasy” hoisted above it, and you would probably find the greater half of the books there to be full of vast rural landscapes, hackneyed elves, made-up Latinate or Greek words, and a small-town hero, (usually male) destined to stop a physically absent overlord associated with darkness, nihilism, or/and industrialization. With this predictability in mind, critics have condemned fantasy as escapist, childish, fake, and dependent upon familiar tropes. Many a great fantasy author, such as the giants Ursula K. Le Guin, J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis and others, has recognized this, and either agreed or disagreed as the particulars are debated. -

Defining Fantasy

1 DEFINING FANTASY by Steven S. Long This article is my take on what makes a story Fantasy, the major elements that tend to appear in Fantasy, and perhaps most importantly what the different subgenres of Fantasy are (and what distinguishes them). I’ve adapted it from Chapter One of my book Fantasy Hero, available from Hero Games at www.herogames.com, by eliminating or changing most (but not all) references to gaming and gamers. My insights on Fantasy may not be new or revelatory, but hopefully they at least establish a common ground for discussion. I often find that when people talk about Fantasy they run into trouble right away because they don’t define their terms. A person will use the term “Swords and Sorcery” or “Epic Fantasy” without explaining what he means by that. Since other people may interpret those terms differently, this leads to confusion on the part of the reader, misunderstandings, and all sorts of other frustrating nonsense. So I’m going to define my terms right off the bat. When I say a story is a Swords and Sorcery story, you can be sure that it falls within the general definitions and tropes discussed below. The same goes for Epic Fantasy or any other type of Fantasy tale. Please note that my goal here isn’t necessarily to persuade anyone to agree with me — I hope you will, but that’s not the point. What I call “Epic Fantasy” you may refer to as “Heroic Fantasy” or “Quest Fantasy” or “High Fantasy.” I don’t really care. -

Exploring Trauma Through Fantasy

IN-BETWEEN WORLDS: EXPLORING TRAUMA THROUGH FANTASY Amber Leigh Francine Shields A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2018 Full metadata for this thesis is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this thesis: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/16004 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4 Abstract While fantasy as a genre is often dismissed as frivolous and inappropriate, it is highly relevant in representing and working through trauma. The fantasy genre presents spectators with images of the unsettled and unresolved, taking them on a journey through a world in which the familiar is rendered unfamiliar. It positions itself as an in-between, while the consequential disturbance of recognized world orders lends this genre to relating stories of trauma themselves characterized by hauntings, disputed memories, and irresolution. Through an examination of films from around the world and their depictions of individual and collective traumas through the fantastic, this thesis outlines how fantasy succeeds in representing and challenging histories of violence, silence, and irresolution. Further, it also examines how the genre itself is transformed in relating stories that are not yet resolved. While analysing the modes in which the fantasy genre mediates and intercedes trauma narratives, this research contributes to a wider recognition of an understudied and underestimated genre, as well as to discourses on how trauma is narrated and negotiated.