Transit Needs and Opportunities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

York Region Transit

The Importance of Service Frequency to Attracting Ridership: The Cases of Brampton and York Jonathan English Columbia University CUTA Conference May 2016 Introduction • Is density the most important determinant of transit system success? • Can transit be successful in areas with relatively low density and a suburban built form? • Do service increases and reductions affect ridership? • The goal is to find natural experiments that can answer these questions The Region Source: Wikimedia The Comparison York Region Transit Brampton Transit • Focused expansion on • Developed grid network major corridors, of high-service bus including pioneering routes Viva BRT • Tailored service to demand on secondary corridors High Frequency Routes York Brampton Green = 20 Min Max Headway to Midnight, Mon to Sat (to 10pm on Sun) Grey = 20 Min Max Headway to Midnight, Mon to Sat (to 10pm on Sun) Source: Public Schedules and Google Earth Principal Findings • Increased service improves ridership performance • “Network effect” means that comprehensive network of high-service routes, rather than focus on select corridors, produces largest ridership gains • Well-designed service improvements can be undertaken while maintaining stable fare recovery Brampton vs York Service 1.8 1.6 1.4 /Capita 1.2 1 0.8 Kilometres 0.6 0.4 Vehicle 0.2 0 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 York Brampton Source: CUTA Fact Book Brampton vs York Ridership 40 35 Brampton: +57.7% 30 25 20 15 Riders/Capita 10 York: +29.7% 5 0 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 -

Bus Rapid Transit Service Breaks Ground in Mississauga

No. H0xx/10 For release August 20, 2010 BUS RAPID TRANSIT SERVICE BREAKS GROUND IN MISSISSAUGA MISSISSAUGA, ONTARIO — Bob Dechert, Member of Parliament, Mississauga-Erindale, the Honourable Kathleen Wynne, Ontario’s Transportation Minister, Her Worship Hazel McCallion, Mayor of Mississauga and Gary McNeil, GO Transit Managing Director participated in a groundbreaking ceremony today to mark the start of construction of the Mississauga Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) corridor. This project, which is expected to be completed in spring 2013, will improve local and inter-regional bus operations across the City of Mississauga. It involves constructing an 11-kilometre east-west busway across the City of Mississauga between Winston Churchill Boulevard and Renforth Drive in the City of Toronto and a total of 12 stations along the route with related commuter facilities. “Investments in public transit creates jobs and boosts the Canadian economy,” said MP Dechert. “This rapid transit system will provide commuters in Mississauga with a more efficient transit option, while cutting commute times and taking more cars off the road.” “This is great news for Mississauga residents,” said Ontario Transportation Minister Kathleen Wynne. “When the new bus rapid transit line is finished, more commuters will be able to leave their cars at home and take public transit. Investing in public transit is part of the McGuinty government’s Open Ontario plan. Better public transit means a better quality of life for Ontario families.” (TBC) “We are doing everything we can to make Mississauga a transit-oriented city and show our commitment to ensure we meet the needs of residents and businesses,” said Mayor Hazel McCallion. -

Profile of Sharon Doyle.Indd

the same brush PROFILE OF SHARON DOYLE, MANAGER, MOBILITY PLUS AT YORK REGION TRANSIT (YRT) Interview location: Scaddabush Restaurant and on YRT in York Region, Ontario, Canada In one word, she describes herself as “Passionate.” By Laura Lee Huttenbach Sharon Doyle is on the phone with the inspector when I arrive at the Richmond Hill bus terminal in York Region, a municipality to the north of Toronto. Next to Sharon on the platform is a man named Michael, who uses a wheelchair. Michael is confused. He can’t tell Sharon exact- ly how he got to the station, and he can’t tell her exactly where he wants to go. He’d tried to board a GO (Gov- ernment of Ontario) bus going to the airport, but was told the bus wasn’t wheelchair accessible. Additional- ly, Michael made it clear he had no flight to catch. With stubble, wearing stained grey sweatpants and a navy hoodie, Michael looks like he may not have showered for a few days. Most people watching the scene edge away from him on the platform, but Sharon, Manager of Mobility Plus for Sharon Doyle, in front of the York fleet, in 2016. (Photo credit Laura Lee Huttenbach.) York Regional Transit (YRT), is close. People Who Move People: a series initiated and funded by 1 need sub headline “I just can’t leave him here all day,” she says to the inspector, Miles, on her phone. She turns to me. “I’m sorry,” she says. “Let me just take care of this, and we can head to lunch.” Michael is looking me up and down. -

POST-ELECTION REPORT “Ontario Election” by Knehcsg Is Licensed Under 2.0 CC BY-SA

POST-ELECTION REPORT “Ontario Election” by knehcsg is licensed under 2.0 CC BY-SA METHODOLOGY CONTACT INFORMATION The analysis in this report is based on results of a survey conducted on In Ottawa: June 28th-30th, and July 14-16th 2018 among a sample of 3005 adults, Quito Maggi, President 18 years of age or older, living in the electoral districts of Don Valley East, [email protected] Don Valley West, Etobicoke North, Mississauga-Erin Mills, Mississauga– In Toronto: Malton, Mississauga Centre, Ottawa South, Scarborough–Guildwood, Dr. Joseph Angolano, Vice President Scarborough Centre, and Scarborough Southwest, as well as 1846 Muslims [email protected] in the province. The survey was conducted using automated telephone interviews (Smart IVR). Respondents were interviews on landlines and Find us online at: cellular phones. The survey is intended to represent the voting population • www.mainstreetresearch.ca in these ten ridings. • twitter.com/MainStResearch • facebook.com/mainstreetresearch The margin of error for the poll is +/- 1.78% at the 95% confidence level. Margins of error are higher in each subsample. The Canadian Muslim Vote: Totals may not add up 100% due to rounding. Ali Manek, Executive Director, [email protected] ABOUT MAINSTREET Hussein Allidina, Board Member, With 20 years of political experience in all three levels of government, [email protected] President and CEO Quito Maggi is a respected commentator on international public affairs. Differentiated by its large sample sizes, Mainstreet Research has provided accurate snapshots of public opinion, having predicted a majority NDP government in Alberta, and was the only polling firm to correctly predict a Liberal majority government in the 2015 federal election. -

Canadian Version

OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE AMALGAMATED TRANSIT UNION | AFL-CIO/CLC JULY / AUGUST 2014 A NEW BEGINNING FOR PROGRESSIVE LABOR EDUCATION & ACTIVISM ATU ACQUIRES NATIONAL LABOR COLLEGE CAMPUS HAPPY LABOUR DAY INTERNATIONAL OFFICERS LAWRENCE J. HANLEY International President JAVIER M. PEREZ, JR. NEWSBRIEFS International Executive Vice President OSCAR OWENS TTC targets door safety woes International Secretary-Treasurer Imagine this: your subway train stops at your destination. The doors open – but on the wrong side. In the past year there have been INTERNATIONAL VICE PRESIDENTS 12 incidents of doors opening either off the platform or on the wrong side of the train in Toronto. LARRY R. KINNEAR Ashburn, ON – [email protected] The Toronto Transit Commission has now implemented a new RICHARD M. MURPHY “point and acknowledge” safety procedure to reduce the likelihood Newburyport, MA – [email protected] of human error when opening train doors. The procedure consists BOB M. HYKAWAY of four steps in which a subway operator must: stand up, open Calgary, AB – [email protected] the window as the train comes to a stop, point at a marker on the wall using their index finger and WILLIAM G. McLEAN then open the train doors. If the operator doesn’t see the marker he or she is instructed not to open Reno, NV – [email protected] the doors. JANIS M. BORCHARDT Madison, WI – [email protected] PAUL BOWEN Agreement in Guelph, ON, ends lockout Canton, MI – [email protected] After the City of Guelph, ON, locked out members of Local 1189 KENNETH R. KIRK for three weeks, city buses stopped running, and transit workers Lancaster, TX – [email protected] were out of work and out of a contract while commuters were left GARY RAUEN stranded. -

Volume 5 Has Been Updated to Reflect the Specific Additions/Revisions Outlined in the Errata to the Environmental Project Report, Dated November, 2017

DISCLAIMER AND LIMITATION OF LIABILITY This Revised Final Environmental Project Report – Volume 5 has been updated to reflect the specific additions/revisions outlined in the Errata to the Environmental Project Report, dated November, 2017. As such, it supersedes the previous Final version dated October, 2017. The report dated October, 2017 (“Report”), which includes its text, tables, figures and appendices) has been prepared by Gannett Fleming Canada ULC (“Gannett Fleming”) and Morrison Hershfield Limited (“Morrison Hershfield”) (“Consultants”) for the exclusive use of Metrolinx. Consultants disclaim any liability or responsibility to any person or party other than Metrolinx for loss, damage, expense, fines, costs or penalties arising from or in connection with the Report or its use or reliance on any information, opinion, advice, conclusion or recommendation contained in it. To the extent permitted by law, Consultants also excludes all implied or statutory warranties and conditions. In preparing the Report, the Consultants have relied in good faith on information provided by third party agencies, individuals and companies as noted in the Report. The Consultants have assumed that this information is factual and accurate and has not independently verified such information except as required by the standard of care. The Consultants accept no responsibility or liability for errors or omissions that are the result of any deficiencies in such information. The opinions, advice, conclusions and recommendations in the Report are valid as of the date of the Report and are based on the data and information collected by the Consultants during their investigations as set out in the Report. The opinions, advice, conclusions and recommendations in the Report are based on the conditions encountered by the Consultants at the site(s) at the time of their investigations, supplemented by historical information and data obtained as described in the Report. -

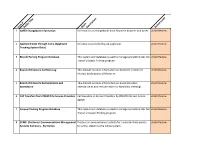

2020 Open Data Inventory

le n it tio T ip lic t r b s c u or e Item # P Sh D Access Level 1 AMEX Chargeback Information Information on chargebacks from Payment Acquirer and Amex Under Review 2 Applicant Data Through Taleo (Applicant Information provided by job applicants Under Review Tracking System Data) 3 Bicycle Parking Program Database This system and database is used to manage and administer GO Under Review Transit's Bicycle Parking program 4 Board of Directors Conflicts Log This dataset contains information on Directors' conflict of Under Review interest declarations at Metrolinx 5 Board of Directors Remuneration and This dataset contains information on Board Directors' Under Review Attendance attendance at and remuneration for Metrolinx meetings 6 Call Transfers from PRESTO to Service Providers Call transfers to Service Providers by PRESTO Contact Centre Under Review Agents 7 Carpool Parking Program Database This system and database is used to manage and administer GO Under Review Transit's Carpool Parking program 8 CCMS (Customer Communications Management Displays all announcement activity for a selected time period Under Review System) Summary - By Station for a line, station or the whole system. 9 CCMS (Customer Communications Management Displays number of messages (total) sent to each customer Under Review System) Summary by Channel channel over a time period. 10 CCMS (Customer Communications Management Displays all messages sent through CCMS for selected time Under Review System) Summary period. Shows what we sent as well as where it was sent and -

Creating Connections in Burlington

CREATING CONNECTIONS IN THE CITY OF BURLINGTON PETER ZUK, CHIEF CAPITAL OFFICER, METROLINX LESLIE WOO, CHIEF PLANNING OFFICER, METROLINX BURLINGTON CITY COUNCIL OCTOBER 30, 2017 CONGESTION COSTS OUR ECONOMY • The average commute in the GTHA is up to 60 minutes. That means the average commuter spends nearly an extra work day a week sitting in their car, stuck in traffic. Congestion is costing the GTHA between $6 BILLION - $11 BILLION A YEAR in lost economic activity. 2 METROLINX CAPITAL PROJECTS GROUP: FOCUS ON THE BUILD PLAN BUILD • Design • Environmental Assessment • Property Acquisition OPERATE • Procurement process • Contract Award • Construction 3 WHAT WE ARE BUILDING METROLINX PLANNED CAPITAL SPEND ASSETS TODAY OVER 10 YEAR PROGRAM $19.5 Billion* over $43 Billion** *March 2017, Audited **Metrolinx 17/18 Business Plan 4 Concrete Ties on the Stouffville Corridor, August 2017. AN INTEGRATED NETWORK 5 RER AND RT – NO SMALL TASK 6 GO RAIL EXPANSION 150 kilometers of new dedicated GO track will allow for more uninterrupted service New electric trains will travel faster for longer and reduce travel times Bridges and tunnels that eliminate intersections with rail and road traffic will provide more reliable GO train service New and improved stations will make your journey more comfortable, from start to finish New electrified rail infrastructure will allow Metrolinx to deliver faster, more frequent service 7 INFRASTRUCTURE 8 RER: NEW AND IMPROVED GO STATIONS As part of the RER Program, Metrolinx will modify and improve a large number of existing stations, build 12 new GO stations on the existing network, and 7 new stations on extensions. -

Cross-Boundary Transit Service Integration Pilot Project

9.8 Date: May 25, 2021 Originator’s files: To: Chair and Members of General Committee From: Geoff Wright, P.Eng, MBA, Commissioner of Meeting date: Transportation and Works June 9, 2021 Subject Cross-Boundary Transit Service Integration Pilot Project Recommendation 1. That the report to General Committee entitled “Cross-Boundary Transit Service Integration Pilot Project” dated May 25, 2021 from the Commissioner of Transportation and Works be received for information. 2. That Phase 1 of the Service Integration Pilot Project recommendations for enhanced cross-boundary travel be received for information. Executive Summary The Ministry of Transportation has convened a Fare and Service Integration (FSI) Provincial-Municipal Table that includes representatives of all transit agencies and aims to improve connections and the customer experience for inter-municipal transit travel. The Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) has engaged a consultant team to develop an agency-driven FSI model to present to the Provincial-Municipal Table in partnership with surrounding transit agencies including MiWay. Currently MiWay, along with several other 905 agencies, are prohibited from providing local service within City of Toronto, resulting in TTC providing duplicate service for their residents. In addition, transit fares are not integrated between the TTC and MiWay. In partnership with the TTC, the Burnhamthorpe Road corridor has been selected for a transit service integration pilot project in the near-term (targeting fall 2021). 9.8 General Committee 2021/05/25 2 Background For decades, transit service integration has been discussed and studied in the Greater Toronto Hamilton Area (GTHA). The Ministry of Transportation’s newly convened Fare and Service Integration (FSI) Provincial-Municipal Table consists of senior representatives from transit systems within the Greater Toronto Hamilton Area (GTHA) and the broader GO Transit service area. -

2016 Census 2018 25-Wards

Etobicoke North City of Toronto Ward Profiles Population Highlights 2016 Census 2018 25-Wards Ward Population 118,040 Population by Age Group 18% Population Growth 0-14 (2011–2016) 0.4% 15% 15% 15-24 Median Age 36.5 12% 27% 25-44 31% Population Growth (2011–2016) 26% 45-64 0.4% 27% Etobicoke North 14% 4.5% 65+ Toronto 16% Bar Chart showing the rate of population growth between the years 2006 and 2016 for the Ward compared to the City of Toronto based on the 2006 and 2016 Census data. For more information, please contact Michael Wright at 416-392-7558 or [email protected] Bar Chart of showing population by age for the Ward compared to the City of Toronto for the year 2016 based on Census data. For more information, please contact Michael Wright at 416-392-7558 or [email protected] Population Growth (2006–2016) Dependency Ratio 3.1% senior and youth dependents Etobicoke North 65.8 for every 100 working age 9.1% persons Toronto Bar Chart showing the rate of population growth between the years 2011 and 2016 for the Ward compared to the City of Toronto based on the 2011 and 2016 Census data. For more information, please contact Michael Wright at 416-392-7558 or [email protected] Density 24 people/hectare 42.3 23.6 34.2 Etobicoke North Etobicoke North 43 people/hectare 30.9 24.2 44.9 Toronto Toronto Bar Chart showing the density (the number of people per hectare) for the Ward compared to the City of Toronto in 2016 based on Census data. -

Transit Planning in Toronto: Roles, Priorities and Our Decision Making Framework

INFORMATION ONLY ____________________________________________________________________________ Subject: Transit Planning in Toronto: roles, priorities and our decision making framework Date: July 29, 2015 At the TTC Board meeting on July 29, 2015, Jennifer Keesmaat, Chief Planner, City of Toronto will deliver a presentation titled “Transit Planning in Toronto: roles, priorities and our decision making framework.” Original signed by Vincent Rodo Chief Financial & Administration Officer 1-17 Transit Planning in Toronto: Roles, Priorities and our decision making framework TTC Board Meeting July 29, 2015 Jennifer Keesmaat, Chief Planner and Executive Director City Planning Division PLANNING A GREAT CITY, TOGETHER Overview of Presentation 1. Role of the City Planning Division in Transit Planning 2. Key Transit Planning Projects • SmartTrack/RER • Relief Line Project Assessment • Scarborough Subway Extension Project Assessment • Metrolinx LRT Program • King Streetcar Enhancements • “Feeling Congested?” Transportation Official Plan Review ruill_TORDNIO 2 City Planning Division PROGRAMS • Application Review • Business Performance & Standards • Civic Design • Committee of Adjustment • Design Review • Community Policy • Environmental Planning • Graphics & Visualization • Heritage Preservation • Official Plan & Zoning By-law • Outreach and Engagement • Public Art • Research & Information • Strategic Initiatives • Transit Planning • Waterfront Renewal 3 Transit Implementation Unit Objective Transit planning in the City of Toronto requires a transparent, -

Rapid Transit in Toronto Levyrapidtransit.Ca TABLE of CONTENTS

The Neptis Foundation has collaborated with Edward J. Levy to publish this history of rapid transit proposals for the City of Toronto. Given Neptis’s focus on regional issues, we have supported Levy’s work because it demon- strates clearly that regional rapid transit cannot function eff ectively without a well-designed network at the core of the region. Toronto does not yet have such a network, as you will discover through the maps and historical photographs in this interactive web-book. We hope the material will contribute to ongoing debates on the need to create such a network. This web-book would not been produced without the vital eff orts of Philippa Campsie and Brent Gilliard, who have worked with Mr. Levy over two years to organize, edit, and present the volumes of text and illustrations. 1 Rapid Transit in Toronto levyrapidtransit.ca TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 INTRODUCTION 7 About this Book 9 Edward J. Levy 11 A Note from the Neptis Foundation 13 Author’s Note 16 Author’s Guiding Principle: The Need for a Network 18 Executive Summary 24 PART ONE: EARLY PLANNING FOR RAPID TRANSIT 1909 – 1945 CHAPTER 1: THE BEGINNING OF RAPID TRANSIT PLANNING IN TORONTO 25 1.0 Summary 26 1.1 The Story Begins 29 1.2 The First Subway Proposal 32 1.3 The Jacobs & Davies Report: Prescient but Premature 34 1.4 Putting the Proposal in Context CHAPTER 2: “The Rapid Transit System of the Future” and a Look Ahead, 1911 – 1913 36 2.0 Summary 37 2.1 The Evolving Vision, 1911 40 2.2 The Arnold Report: The Subway Alternative, 1912 44 2.3 Crossing the Valley CHAPTER 3: R.C.