Japanese Internment at Topaz by Lisa Barr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Wittelsbach-Graff and Hope Diamonds: Not Cut from the Same Rough

THE WITTELSBACH-GRAFF AND HOPE DIAMONDS: NOT CUT FROM THE SAME ROUGH Eloïse Gaillou, Wuyi Wang, Jeffrey E. Post, John M. King, James E. Butler, Alan T. Collins, and Thomas M. Moses Two historic blue diamonds, the Hope and the Wittelsbach-Graff, appeared together for the first time at the Smithsonian Institution in 2010. Both diamonds were apparently purchased in India in the 17th century and later belonged to European royalty. In addition to the parallels in their histo- ries, their comparable color and bright, long-lasting orange-red phosphorescence have led to speculation that these two diamonds might have come from the same piece of rough. Although the diamonds are similar spectroscopically, their dislocation patterns observed with the DiamondView differ in scale and texture, and they do not show the same internal strain features. The results indicate that the two diamonds did not originate from the same crystal, though they likely experienced similar geologic histories. he earliest records of the famous Hope and Adornment (Toison d’Or de la Parure de Couleur) in Wittelsbach-Graff diamonds (figure 1) show 1749, but was stolen in 1792 during the French T them in the possession of prominent Revolution. Twenty years later, a 45.52 ct blue dia- European royal families in the mid-17th century. mond appeared for sale in London and eventually They were undoubtedly mined in India, the world’s became part of the collection of Henry Philip Hope. only commercial source of diamonds at that time. Recent computer modeling studies have established The original ancestor of the Hope diamond was that the Hope diamond was cut from the French an approximately 115 ct stone (the Tavernier Blue) Blue, presumably to disguise its identity after the that Jean-Baptiste Tavernier sold to Louis XIV of theft (Attaway, 2005; Farges et al., 2009; Sucher et France in 1668. -

Pearl Accessories Operator's Manual

Pearl® Trilogy Accessories Manual CE Marking: This product (model number 5700-DS) is a CE-marked product. For conformity information, contact LI-COR Support at http://www.licor.com/biotechsupport. Outside of the U.S., contact your local sales office or distributor. Notes on Safety LI-COR products have been designed to be safe when operated in the manner described in this manual. The safety of this product cannot be guaranteed if the product is used in any other way than is specified in this manual. The Pearl® Docking Station and Pearl Clean Box is intended to be used by qualified personnel. Read this entire manual before using the Pearl Docking Station and Pearl Clean Box. Equipment Markings: The product is marked with this symbol when it is necessary for you to refer to the manual or accompanying documents in order to protect against damage to the product. The product is marked with this symbol when a hazardous voltage may be present. Manual Markings: WARNING Warnings must be followed carefully to avoid bodily injury. CAUTION Cautions must be observed to avoid damaging your equipment. NOTE Notes contain additional information and useful tips. IMPORTANT Information of importance to prevent procedural mistakes in the operation of the equipment or related software. Failure to comply may result in a poor experimental outcome but will not cause bodily injury or equipment damage. Federal Communications Commission Radio Frequency Interference Statement WARNING: This equipment generates, uses, and can radiate radio frequency energy and if not installed in accordance with the instruction manual, may cause interference to radio communications. -

2000 Foot Problems at Harris Seminar, Nov

CALIFORNIA THOROUGHBRED Adios Bill Silic—Mar. 79 sold at Keeneland, Oct—13 Adkins, Kirk—Nov. 20p; demonstrated new techniques for Anson, Ron & Susie—owners of Peach Flat, Jul. 39 2000 foot problems at Harris seminar, Nov. 21 Answer Do S.—won by Full Moon Madness, Jul. 40 JANUARY TO DECEMBER Admirably—Feb. 102p Answer Do—Jul. 20; 3rd place finisher in 1990 Cal Cup Admise (Fr)—Sep. 18 Sprint, Oct. 24; won 1992 Cal Cup Sprint, Oct. 24 Advance Deposit Wagering—May. 1 Anthony, John Ed—Jul. 9 ABBREVIATIONS Affectionately—Apr. 19 Antonsen, Per—co-owner stakes winner Rebuild Trust, Jun. AHC—American Horse Council Affirmed H.—won by Tiznow, Aug. 26 30; trainer at Harris Farms, Dec. 22; cmt. on early training ARCI—Association of Racing Commissioners International Affirmed—Jan. 19; Laffit Pincay Jr.’s favorite horse & winner of Tiznow, Dec. 22 BC—Breeders’ Cup of ’79 Hollywood Gold Cup, Jan. 12; Jan. 5p; Aug. 17 Apollo—sire of Harvest Girl, Nov. 58 CHRB—California Horse Racing Board African Horse Sickness—Jan. 118 Applebite Farms—stand stallion Distinctive Cat, Sep. 23; cmt—comment Africander—Jan. 34 Oct. 58; Dec. 12 CTBA—California Thoroughbred Breeders Association Aga Khan—bred Khaled in England, Apr. 19 Apreciada—Nov. 28; Nov. 36 CTBF—California Thoroughbred Breeders Foundation Agitate—influential broodmare sire for California, Nov. 14 Aptitude—Jul. 13 CTT—California Thorooughbred Trainers Agnew, Dan—Apr. 9 Arabian Light—1999 Del Mar sale graduate, Jul. 18p; Jul. 20; edit—editorial Ahearn, James—co-author Efficacy of Breeders Award with won Graduation S., Sep. 31; Sep. -

Special September

March 28, 2018 .COM September 9, 2019 SPECIAL SEPTEMBER The Thoroughbreds That Broke Ground In The Air By Joe Nevills There are 20 horses cataloged painted a blue-sky picture of what for this year’s Keeneland Septem- air travel could hold for the future of ber Yearling Sale that were born Thoroughbred racing. overseas and arrived stateside by airplane, and considerably more “This latest way of shipping racers of the auction’s 4,644 entries will will eventually become popular in travel through the sky to destina- that it would enable a horse to tions in different states and different race one afternoon over the New hemispheres after selling to far-flung York tracks and fill his engage- buyers. ment over a Chicago track the next afternoon. The world do When stacked against van and rail move.” travel, which have hauled Thor- oughbreds since the mid-1800s, Everything went to plan except for and transit by ship, which has been the race itself. Wirt G. Bowman was around as long as travelers cross- KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION part of a hot pace in the Spreckles, ing the ocean have needed horses Early air travel but he faded late to finish fifth. in their new destinations, air travel Continued on Page 7 is a relatively new kid on the block. The Wright Brothers first left the ground in Kitty Hawk, N.C. in 1903, and the first Thoroughbred was shipped by plane a quarter-century later. The vanguard for air travel among Thoroughbred racehorses was Wirt G. Bowman, a prized runner from the stable of Cali- fornia hotel and nightclub owner Baron Long. -

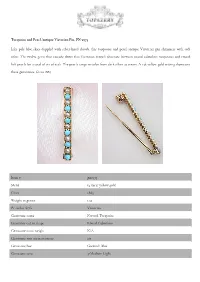

Turquoise and Pearl Antique Victorian Pin, PN-2973 Like Pale Blue Skies

Turquoise and Pearl Antique Victorian Pin, PN-2973 Like pale blue skies dappled with silver-lined clouds, this turquoise and pearl antique Victorian pin shimmers with soft color. The twelve gems that cascade down this Victorian brooch alternate between round cabochon turquoises and round half pearls for a total of six of each. The pearls range in color from dark silver to cream. A 14k yellow gold setting showcases these gemstones. Circa 1885 Item # pn2973 Metal 14 karat yellow gold Circa 1885 Weight in grams 1.22 Period or Style Victorian Gemstone name Natural Turquoise Gemstone cut or shape Round Cabochon Gemstone carat weight N/A Gemstone mm measurements 2.0 Gemstone hue Greenish Blue Gemstone tone 4-Medium Light Gemstone saturation 5-Strong Gemstone # of stones 6 Number of pearls 6 Pearl shape Round Half Pearls Pearl size 2.0 Pearl color Dark Silver White and Cream White Pearl overtone None Other pearl info Natural Half Pearls Length 26.8 mm [1.05 in] Width of widest point 3.66 mm [0.14 in] Important Jewelry Information Each antique and vintage jewelry piece is sent off site to be evaluated by an appraiser who is not a Topazery employee and who has earned the GIA Graduate Gemologist diploma as well as the title of AGS Certified Gemologist Appraiser. The gemologist/appraiser's report is included on the Detail Page for each jewelry piece. An appraisal is not included with your purchase but we are pleased to provide one upon request at the time of purchase and for an additional fee. -

Plan De Compensación Global Definición De Volúmenes Volume Definitions

Plan de compensación Global www.globalimpacteam.com Definición de Volúmenes www.globalimpacteam.com Volume Definitions ▪ Qualifying Volume - QV ▪ Used to qualify for Ranks ▪ Commissionable Volume - CV ▪ The volume on which commissions are paid ▪ Starter Pack Volume - SV ▪ Volume on enrollment (Starter packs) for Team Bonus calculations ▪ Kyäni Volume – KV ▪ Volume used in calculating Kyäni Care Loyalty Bonus Genealogy Trees Paygate Team Bonus Fast Start Sponsor Bonus Fast Track Generation Matching Car Program Rank Bonus Ranks - Placement Tree, QV Personal Volume Group Volume Volume Outside Volume Outside KYÄNI RANK (QV) (QV) Largest Leg Largest Two Legs Qualified 100 Distributor Garnet 100 300 100 Jade 100 2000 800 Pearl 100 5,000 2,000 Sapphire 100 10,000 4,000 500 Ruby 100 25,000 10,000 1,250 Emerald 100 50,000 20,000 2,500 Diamond 100 100,000 40,000 5,000 Blue Diamond 100 250,000 100,000 12,500 Green Diamond 100 500,000 200,000 25,000 Purple Diamond 100 1,000,000 400,000 50,000 Red Diamond 100 2,000,000 800,000 100,000 Double Red 100 4,000,000 1,600,000 200,000 Diamond Black Diamond 100 10,000,000 4,000,000 500,000 Double Black 100 25,000,000 10,000,000 1,250,000 Diamond Team Bonus Level Payout Paid Level 6 (5% of SV) Team Bonus (Requires Sapphire Rank) Rank Required % of SV Level Distributor/ Paid Level 5 (5% of SV) Level 1 Qualified 25% (Requires Pearl Rank) Distributor Level 2 Garnet 10% Paid Level 4 (5% of SV) (Requires Jade Rank) Level 3 Jade 5% Level 4 Jade 5% Level 5 Pearl 5% Paid Level 3 (5% of SV) (Requires Jade Rank) Sapphire -

Cultured a Balone Blister Pearls from New Zealand

CULTU RED ABALONE BLISTER PEARLS FROM NEW ZEA LAND By Cheryl Y. Wentzell The successful culturing of abalone pearls balone pearls are highly prized for their rarity, has been known since French scientist dynamic colors, and remarkable iridescence. Louis Boutan’s experimentation in the late Their unusual shapes—often conica l—and 1890s, but commercial production has Apotentially large sizes make these pearls especially well suit - been achieved only in recent decades. The ed for designer jewelry. The beauty of these rare pearls has use of New Zealand’s Haliotis iris , with its spawned several attempts at culturing, recorded as far back colorful and iridescent nacre, has had the as the late 19th century. However, these early attempts strongest recent impact on this industry. Empress Abalone Ltd. is producing large, encountered many obstacles. Only recently have researchers attractive cultured blister pearls in H. iris . begun to overcome the challenges and difficulties presented The first commercial harvest in 1997 yield - by abalone pearl culture. One company, Empress Abalone ed approximately 6,000 jewelry-quality Ltd. of Christchurch, New Zealand, is successfully culturing cultured blister pearls, 9–20 mm in diame - brightly colored blister pearls within New Zealand’s ter, with vibrant blue, green, purple, and Haliotis iris (figure 1). These assembled cultured blister pink hues. Examination of 22 samples of pearls are marketed under the international trademark, this material by standard gemological and Empress Pearl © (or Empress Abalone Pearl © in the U.S.). The advanced testing methods revealed that company is also pursuing the commercial production of the presence and thicknesses of the conchi - whole spherical cultured abalone pearls. -

CRAFTING SURVIVAL in JAPANESE AMERICAN CONCENTRATION CAMPS Jane E. Dusse

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: ARTFUL IDENTIFICATIONS: CRAFTING SURVIVAL IN JAPANESE AMERICAN CONCENTRATION CAMPS Jane E. Dusselier, Doctor of Philosophy, 2005 Dissertation directed by: Associate Professor, Seung-kyung Kim Department of Women’s Studies “Artful Identifications” offers three meanings of internment art. First, internees remade locations of imprisonment into livable places of survival. Inside places were remade as internees responded to degraded living conditions by creating furniture with discarded apple crates, cardboard, tree branches and stumps, scrap pieces of wood left behind by government carpenters, and wood lifted from guarded lumber piles. Having addressed the material conditions of their living units, internees turned their attention to aesthetic matters by creating needle crafts, wood carvings, ikebana, paintings, shell art, and kobu. Dramatic changes to outside spaces of “assembly centers” and concentration camps were also critical to altering hostile settings into survivable landscapes My second meaning positions art as a means of making connections, a framework offered with the hope of escaping utopian models of community building which overemphasize the development of common beliefs, ideas, and practices that unify people into easily surveilled groups. “Making Connections” situates the process of individuals identifying with larger collectivities in the details of everyday life, a complicated and layered process that often remains invisible to us. By sewing clothes for each other, creating artificial flowers and lapel pins as gifts, and participating in classes and exhibits, internees addressed their needs for maintaining and developing connections. “Making Connections” advances perhaps the broadest possible understanding of identity formation based on the idea of employing diverse art forms to sustain already developed relationships and creating new attachments in the context of displacement. -

Winter 1998 Gems & Gemology

WINTER 1998 VOLUME 34 NO. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS 243 LETTERS FEATURE ARTICLES 246 Characterizing Natural-Color Type IIb Blue Diamonds John M. King, Thomas M. Moses, James E. Shigley, Christopher M. Welbourn, Simon C. Lawson, and Martin Cooper pg. 247 270 Fingerprinting of Two Diamonds Cut from the Same Rough Ichiro Sunagawa, Toshikazu Yasuda, and Hideaki Fukushima NOTES AND NEW TECHNIQUES 281 Barite Inclusions in Fluorite John I. Koivula and Shane Elen pg. 271 REGULAR FEATURES 284 Gem Trade Lab Notes 290 Gem News 303 Book Reviews 306 Gemological Abstracts 314 1998 Index pg. 281 pg. 298 ABOUT THE COVER: Blue diamonds are among the rarest and most highly valued of gemstones. The lead article in this issue examines the history, sources, and gemological characteristics of these diamonds, as well as their distinctive color appearance. Rela- tionships between their color, clarity, and other properties were derived from hundreds of samples—including such famous blue diamonds as the Hope and the Blue Heart (or Unzue Blue)—that were studied at the GIA Gem Trade Laboratory over the past several years. The diamonds shown here range from 0.69 to 2.03 ct. Photo © Harold & Erica Van Pelt––Photographers, Los Angeles, California. Color separations for Gems & Gemology are by Pacific Color, Carlsbad, California. Printing is by Fry Communications, Inc., Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania. © 1998 Gemological Institute of America All rights reserved. ISSN 0016-626X GIA “Cut” Report Flawed? The long-awaited GIA report on the ray-tracing analysis of round brilliant diamonds appeared in the Fall 1998 Gems & Gemology (“Modeling the Appearance of the Round Brilliant Cut Diamond: An Analysis of Brilliance,” by T. -

The Tanforan Memorial Project: How Art and History Intersected

THE TANFORAN MEMORIAL PROJECT: HOW ART AND HISTORY INTERSECTED A Thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University AS In partial fulfillment of 5 0 the requirements for the Degree AOR- • 033 Master of Arts in Humanities by Richard J. Oba San Francisco, California Fall Term 2017 Copyright by Richard J. Oba 2017 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read “The Tanforan Memorial Project: How Art and History Intersected” by Richard J. Oba, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts in Humanities at San Francisco State University. I Saul Steier, Associate Professor, Humanities “The Tanforan Memorial Project: How Art and History Intersected” Richard J. Oba San Francisco 2017 ABSTRACT Many Japanese Americans realize that their incarceration during WWII was unjust and patently unconstitutional. But many other American citizens are often unfamiliar with this dark chapter of American history. The work of great visual artists like Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange, Chiura Obata, Mine Okubo, and others, who bore witness to these events convey their horror with great immediacy and human compassion. Their work allows the American society to visualize how the Japanese Americans were denied their constitutional rights in the name of national security. Without their visual images, the chronicling of this historical event would have faded into obscurity. I certify that the Abstract is a correct representation of the content of this Thesis ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to acknowledge the support and love of my wife, Sidney Suzanne Pucek, May 16, 1948- October 16, 2016. -

Extensions of Remarks E244 HON. MIKE ROGERS HON. DAN

E244 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks March 1, 2006 actively involved in philanthropy and charitable COMMENDING THE PEACE CORPS Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order work. Their generosity has helped countless ON ITS 45TH ANNIVERSARY OF 9066 authorizing the Secretary of War to de- individuals both in their hometown of Grand ITS INCEPTION fine military areas in which ‘‘the right of any Rapids and across Michigan. Institutions such person to enter, remain in or leave shall be as the DeVos Children’s Hospital, the Cook- HON. DAN BURTON subject to whatever restrictions’’ are deemed DeVos Center for Health Sciences, and the OF INDIANA ‘‘necessary or desirable.’’ DeVos Campus of Grand Valley State Univer- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES By the spring of 1942, California, Oregon, sity bear witness to their commitment to give Washington, and Arizona were designated as Wednesday, March 1, 2006 back to the community. military areas. Mr. BURTON of Indiana. Mr. Speaker, I In May of 1942, Santa Clara Valley Japa- Richard DeVos has also written three books would like to take this opportunity to commend nese Americans were ordered to ‘‘close their that have inspired innovative and entrepre- and congratulate the Peace Corps, and its affairs promptly, and make their own arrange- neurial spirits in younger generations. After many volunteers, on the 45th Anniversary of ments for disposal of personal and real prop- undergoing a heart transplant in 1997, Mr. its inception. During a 1960 visit to the Univer- erty.’’ DeVos became the chairman of the Speakers sity of Michigan, then-Senator John F. Ken- Official government fliers were posted Bureau for United Network for Organ Sharing nedy challenged students to not only better around California, Arizona and Washington in- and has worked diligently to deliver his mes- themselves academically, but to serve the call structing families to report to various assembly sage of perseverance and hope. -

Fang Family San Francisco Examiner Photograph Archive Negative Files, Circa 1930-2000, Circa 1930-2000

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/hb6t1nb85b No online items Finding Aid to the Fang family San Francisco examiner photograph archive negative files, circa 1930-2000, circa 1930-2000 Bancroft Library staff The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ © 2010 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Fang family San BANC PIC 2006.029--NEG 1 Francisco examiner photograph archive negative files, circa 1930-... Finding Aid to the Fang family San Francisco examiner photograph archive negative files, circa 1930-2000, circa 1930-2000 Collection number: BANC PIC 2006.029--NEG The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Finding Aid Author(s): Bancroft Library staff Finding Aid Encoded By: GenX © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: Fang family San Francisco examiner photograph archive negative files Date (inclusive): circa 1930-2000 Collection Number: BANC PIC 2006.029--NEG Creator: San Francisco Examiner (Firm) Extent: 3,200 boxes (ca. 3,600,000 photographic negatives); safety film, nitrate film, and glass : various film sizes, chiefly 4 x 5 in. and 35mm. Repository: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Abstract: Local news photographs taken by staff of the Examiner, a major San Francisco daily newspaper.