Why a Hindu Nationalist Party Furthered Globalisation in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2015-2016 Research Themes

Annual Report 2015-2016 Research Themes The research themes of the initiative are explored through public lectures, seminars, conferences, films, research projects, and outreach.� The Initiative currently conducts research on the following themes: 1 Indian Urbanization: Governance, Politics and Political Economy 2 Economic Inequalities and Change 3 Pluralism and Diversities 4 Democracy Above: Engaged audience at Student Fellowship Presentation Front Cover: Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus at Sunset. Mumbai, India. Image: Paul Prescot 1 OP Jindal Distinguished Lecture Series To promote a serious discussion of politics, economics, social and cultural change in modern India, Sajjan and Sangita Jindal have endowed, in perpetuity, the OP Jindal Distinguished Lectures by major scholars and public figures.� Fall 2015 MONTEK SINGH AHLUWALIA and also in books. He co-authored Re-distribution In October 2015, Montek Singh Ahluwalia with Growth: An Approach to Policy (1975). He delivered the OP Jindal Distinguished Lectures. also wrote, “Reforming the Global Financial Ahluwalia has served as a high-level government Architecture”, which was published in 2004 as official in India, as well as with the IMF and the Economic paper No.41 by the Commonwealth World Bank. He has been a key figure in India’s Secretariat, London. Ahluwalia is an honorary economic reforms since the mid-1980s. Most fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford and a member recently, Ahluwalia was Deputy Chairman of the of the Governing Council of the Global Green Planning Commission from July 2004 till May Growth Institute, a new international organization 2014. In addition to this Cabinet level position, based in South Korea. He is a member of the Ahluwalia was a Special Invitee to the Cabinet Alpbach-Laxenburg Group established by the and several Cabinet Committees. -

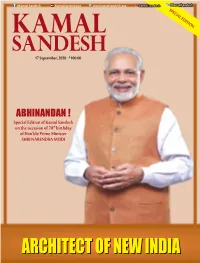

Architect of New India Fortnightly Magazine Editor Prabhat Jha

@Kamal.Sandesh KamalSandeshLive www.kamalsandesh.org kamal.sandesh @KamalSandesh SPECIAL EDITION 17 September, 2020 `100.00 ABHINANDAN ! Special Edition of Kamal Sandesh on the occasion of 70th birthday of Hon’ble Prime Minister SHRI NARENDRA MODI ARCHITECTARCHITECT OFOF NNEWEWArchitect ofII NewNDINDI India KAMAL SANDESHAA 1 Self-reliant India will stand on five Pillars. First Pillar is Economy, an economy that brings Quantum Jump rather than Incremental change. Second Pillar is Infrastructure, an infrastructure that became the identity of modern India. Third Pillar is Our System. A system that is driven by technology which can fulfill the dreams of the 21st century; a system not based on the policy of the past century. Fourth Pillar is Our Demography. Our Vibrant Demography is our strength in the world’s largest democracy, our source of energy for self-reliant India. The fifth pillar is Demand. The cycle of demand & supply chain in our economy is the strength that needs to be harnessed to its full potential. SHRI NARENDRA MODI Hon’ble Prime Minister of India 2 KAMAL SANDESH Architect of New India Fortnightly Magazine Editor Prabhat Jha Executive Editor Dr. Shiv Shakti Bakshi Associate Editors Ram Prasad Tripathy Vikash Anand Creative Editors Vikas Saini Bhola Roy Digital Media Rajeev Kumar Vipul Sharma Subscription & Circulation Satish Kumar E-mail [email protected] [email protected] Phone: 011-23381428, FAX: 011-23387887 Website: www.kamalsandesh.org 04 EDITORIAL 46 2016 - ‘IndIA IS NOT 70 YEARS OLD BUT THIS JOURNEY IS -

Politics of Coalition in India

Journal of Power, Politics & Governance March 2014, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 01–11 ISSN: 2372-4919 (Print), 2372-4927 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development Politics of Coalition in India Farooq Ahmad Malik1 and Bilal Ahmad Malik2 Abstract The paper wants to highlight the evolution of coalition governments in india. The evaluation of coalition politics and an analysis of how far coalition remains dynamic yet stable. How difficult it is to make policy decisions when coalition of ideologies forms the government. More often coalitions are formed to prevent a common enemy from the government and capturing the power. Equally interesting is the fact a coalition devoid of ideological mornings survives till the enemy is humbled. While making political adjustments, principles may have to be set aside and in this process ideology becomes the first victim. Once the euphoria victory is over, differences come to the surface and the structure collapses like a pack of cards. On the grounds of research, facts and history one has to acknowledge india lives in politics of coalition. Keywords: india, government, coalition, withdrawal, ideology, partner, alliance, politics, union Introduction Coalition is a phenomenon of a multi-party government where a number of minority parties join hands for the purpose of running the government which is otherwise not possible. A coalition is formed when many groups come into common terms with each other and define a common programme or agenda on which they work. A coalition government always remains in pulls and pressures particularly in a multinational country like india. -

Political Economy of India's Fiscal and Financial Reform*

Working Paper No. 105 Political Economy of India’s Fiscal and Financial Reform by John Echeverri-Gent* August 2001 Stanford University John A. and Cynthia Fry Gunn Building 366 Galvez Street | Stanford, CA | 94305-6015 * Associate Professor, Department of Government and Foreign Affairs, University of Virginia 1 Although economic liberalization may involve curtailing state economic intervention, it does not diminish the state’s importance in economic development. In addition to its crucial role in maintaining macroeconomic stability, the state continues to play a vital, if more subtle, role in creating incentives that shape economic activity. States create these incentives in a variety of ways including their authorization of property rights and market microstructures, their creation of regulatory agencies, and the manner in which they structure fiscal federalism. While the incentives established by the state have pervasive economic consequences, they are created and re-created through political processes, and politics is a key factor in explaining the extent to which state institutions promote efficient and equitable behavior in markets. India has experienced two important changes that fundamentally have shaped the course of its economic reform. India’s party system has been transformed from a single party dominant system into a distinctive form of coalitional politics where single-state parties play a pivotal role in making and breaking governments. At the same time economic liberalization has progressively curtailed central government dirigisme and increased the autonomy of market institutions, private sector actors, and state governments. In this essay I will analyze how these changes have shaped the politics of fiscal and financial sector reform. -

Shake Hands and Make up 0

NEWSBEAT Shake hands and make up Chief minister Ramakrishna Hegde and the dissidents, led by H. D. Deve Gowda, have called a truce. But, given the belligerence of both sides, how long will it last? ast week, Sunday wondered In fact, there is a persistent suspicion whether Ajit Singh, the new that in spite of the Express'reference to young president of the Janata central government sources, the trans Party would accept Ramak cript came from Bangalore. Who stands rishna Hegde’s resignation. to gain the most from exposing a nexus This week, the answer is in. Yet anotherbetween Ajit Singh and Deve Gowda ofL Hegde’s resignation dramas has ask the cynics. Obviously, it is the chief drawn curtains prematurely. It was up minister. staged by a bigger story: the transcript The chief minister, of course, loudly of the phone conversation between Ajit denied his involvement. In fact, he tried Singh and Janata rebel leader H.D. Deve to give yet another tape episode Gowda, that appeared in Ihe Indian the political. mileage he had ex Express on 10 July. tracted from the Veerappa Moily -Byre The timing was devastating enough to Gowda tapes. This time hewasmuch look suspiciously like a deliberate plant. more subdued. But he is still the injured It came on the eve of Hegde’s departure innocent. “You know, even my phone is to Delhi for the crucial Janata Parliamen tapped, ” he said in Bangalore. So will he Hegde being welcomed by loyalists on his tary Board meeting. Worse. It was not lodge a protest with the central return from Delhi: triumphant carried along with the full text of government? “I have done it so many Hegde’s conditional resignation to Ajit times, what is the use?” he replied. -

Cm of Karnataka List Pdf

Cm of karnataka list pdf Continue CHIEF MINISTERS OF KARNATAKA Since 1947 SL.NO. Date from date to 1. Sri K.CHENGALARAY REDDY 25-10-1947 30-03-1952 2. Sri K.HANUMANTAYA 30-03-1952 19-08-1956 3. Sri KADIDAL MANJAPPA 19-08-1956 31-10-1956 4. Sri S.NIALINGAPPA 01-11-1956 16-05-1958 5. Sri B.D. JATTI 16-05-1958 09-03-1962 6. Sri S.R.Kanthi 14-03-1962 20-06-1962 7. Sri S.NIALINGAPPA 21-06-1962 28-05-1968 8. Shri VERENDRA PATIL 29-05-1968 18-03-1971 9. PRESIDENTIAL RULE 19-03-1971 20-03-1972 10. Sri D.DEVRAJ URS 20-03-1972 31-12-1977 11. RULE PRESIDENTS 31-12-1977 28-02-1978 12. Sri D.DEVARAJ URS 28-02-1978 07-01-1980 13. Sri R.GUNDU RAO 12-01-1980 06-01- 1983 14. Sri RAMAKRISHNA HEGDE 10-01-1983 29-12-1984 15. Sri RAMAKRISHNA HEGDE 08-03-1985 13-02-1986 16. Sri RAMAKRISHNA HEGDE 16-02-1986 10-08-1988 17. Sri S.R.BOOMMAI 13-08-1988 21-04-1989 18. PRESIDENTIAL RULE 21-04-1989 30-11-1989 19. Shri VERENDRA PATIL 30-11-1989 10-10-1990 20. PRESIDENTIAL RULE 10-10-1990 17-10-1990 21. Sri S.BANGARAPPA 17-10-1990 19-11-1992 22. Sri VEERAPPA MOILY 19-11-1992 11-12-1994 23. Sri H.D. DEVEGOVDA 11-12-1994 31-05-1996 24. Sri J.H.PATEL 31-05-1996 07-10-1999 25. -

The Fall-Out of a New Political Regime in India

ASIEN, (Juli 1998) 68, S. 5-20 The Fall-out of a New Political Regime in India Dietmar Rothermund Eine "rechte" Koalition geführt von der Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) hat das "Congress System" abgelöst, das darin bestand, daß sich eine "Zentrumspartei" durch die Polarisation von rechter und linker Opposition an der Macht erhielt. Wahlallianzen der BJP haben regionalen Parteien zu Sitzen verholfen, die früher im Schatten der nationalen Parteien standen. So verschaffte sich die BJP Koali- tionspartner. Die Wähler haben der BJP kein überzeugendes Mandat erteilt, dennoch führte sie ihr Programm durch, zu dem die Atomtests gehörten, die dann in der Bevölkerung breite Zustimmung fanden. Die BJP fühlt sich so dazu ermutigt, eine sehr selbstbewußte Außenpolitik zu betreiben. Dazu gehört auch die Betonung der wirtschaftlichen Eigenständigkeit (Swadeshi). Der am 1.6.1998 vorgelegte Staatshaushalt zeigt kein Entgegenkommen gegenüber ausländischen Investoren. Den angekündigten amerikanischen Sanktionen wurde mit einer Rücklage begegnet und die Verteidigungsausgaben um 14 Prozent erhöht. The formation of a government led by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is certainly a new departure in Indian politics. All previous governments were formed either by the Indian National Congress or by politicians who had earlier belonged to that party. The BJP and its precursor the Bharatiya Jan Sangh had always been in the opposition with the exception of the brief interlude of the Janata government (1977- 1980) in which the present Prime Minister, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, held the post of Minister of External Affairs. The BJP has consistently stood for Hindu nationalism and has attacked the secularism of the Congress as a spurious ideology which should be replaced by genuine secularism. -

The Pioneer Prime Minister Atal

Year 2002 Vajpayee Doublespeak 'GUJARAT BOOSTED SECULARISM DEBATE' December 26 2002 Source: The Pioneer Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee feels that the energy that had erupted in Gujarat needs to be properly channelised. He also thinks that the Gujarat outcome will help the nation understand secularism in the proper perspective. "Ab Shabdon ke sahi aarth lagaye ja rahe hain," Mr Vajpayee said in an interview with Hindi daily Dainik Bhaskar, hinting that the true meaning of these words was being understood now. "Secularism had become a slogan. No attempt was being made to probe what the real form of secularism should be. It was not being debated. Little wonder, we remain fiercely secular for 364 days and launch an election campaign from temples on the 365th day," he remarked. "Unhe Deviji ke mandir mein puja karke abhiyan chalane mein koi aapatti nahin hoti," Mr Vajpayee quipped. He was probably taking a dig at Congress President Sonia Gandhi who had launched her election campaign in Gujarat after offering puja at Ambaji temple. He burst into laughter when asked if his Government, too, was surviving because of "Deviji", hinting that he faced no real threat from the Opposition as long as Mrs Sonia Gandhi remained the Congress president. Asked if the Gujarat episode would help him keep the country united, Mr Vajpayee said, "Ye jo urja nikali hai, use santulit rakhna hoga. Aur ise is yukti se nirman mein lagana hoga jisase hamare jeewan ke jo mulya hain, unki rakhsa ho sake (The energy that has been generated should be kept in balance. -

Leader of the House F

LEADER OF THE HOUSE F. No. RS. 17/5/2005-R & L © RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT, NEW DELHI http://parliamentofindia.nic.in http://rajyasabha.nic.in E-mail: [email protected] RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT PUBLISHED BY SECRETARY-GENERAL, RAJYA SABHA AND NEW DELHI PRINTED BY MANAGER, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PRESS, MINTO ROAD, NEW DELHI-110002. PREFACE This booklet is part of the Rajya Sabha Practice and Procedure Series which seeks to describe, in brief, the importance, duties and functions of the Leader of the House. The booklet is intended to serve as a handy guide for ready reference. The information contained in it is synoptic and not exhaustive. New Delhi DR. YOGENDRA NARAIN February, 2005 Secretary-General THE LEADER OF THE HOUSE Leader of the House in Rajya Sabha Importance of the Office Rule 2(1) of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in the Council of States (Rajya Sabha) defines There are quite a few functionaries in Parliament who the Leader of Rajya Sabha as follows: render members’ participation in debates more real, effective and meaningful. One of them is the 'Leader of "Leader of the Council" means the Prime Minister, the House'. The Leader of the House is an important if he is a member of the Council, or a Minister who parliamentary functionary who exercises direct influence is a member of the Council and is nominated by the on the course of parliamentary business. Prime Minister to function as the Leader of the Council. Origin of Office in England In Rajya Sabha, the following members have served In England, one of the members of the Government, as the Leaders of the House since 1952: who is primarily responsible to the Prime Minister for the arrangement of the government business in the Name Period House of Commons, is known as the Leader of the House. -

Political Parties in India

A M K RESOURCE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE www.amkresourceinfo.com Political Parties in India India has very diverse multi party political system. There are three types of political parties in Indiai.e. national parties (7), state recognized party (48) and unrecognized parties (1706). All the political parties which wish to contest local, state or national elections are required to be registered by the Election Commission of India (ECI). A recognized party enjoys privileges like reserved party symbol, free broadcast time on state run television and radio in the favour of party. Election commission asks to these national parties regarding the date of elections and receives inputs for the conduct of free and fair polls National Party: A registered party is recognised as a National Party only if it fulfils any one of the following three conditions: 1. If a party wins 2% of seats in the Lok Sabha (as of 2014, 11 seats) from at least 3 different States. 2. At a General Election to Lok Sabha or Legislative Assembly, the party polls 6% of votes in four States in addition to 4 Lok Sabha seats. 3. A party is recognised as a State Party in four or more States. The Indian political parties are categorized into two main types. National level parties and state level parties. National parties are political parties which, participate in different elections all over India. For example, Indian National Congress, Bhartiya Janata Party, Bahujan Samaj Party, Samajwadi Party, Communist Party of India, Communist Party of India (Marxist) and some other parties. State parties or regional parties are political parties which, participate in different elections but only within one 1 www.amkresourceinfo.com A M K RESOURCE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE state. -

In This Issue... Plus

Volume 18 No. 2 February 2009 12 in this issue... 6 Vibrant Gujarat 8 India Inc. at Davos 12 15th Partnership Summit 22 3rd Sustainability Summit 8 31 Defence Industry Seminar plus... n India Rubber Expo 2009 n The Power of Cause & Effect n India’s Tryst with Corporate Governance 22 n India & the World n Regional Round Up n And all our regular features We welcome your feedback and suggestions. Do write to us at 31 [email protected] Edited, printed and published by Director General, CII on behalf of Confederation of Indian Industry from The Mantosh Sondhi Centre, 23, Institutional Area, Lodi Road, New Delhi-110003 Tel: 91-11-24629994-7 Fax: 91-11-24626149 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cii.in Printed at Aegean Offset Printers F-17 Mayapuri Industrial Area, Phase II, New Delhi-110064 Registration No. 34541/79 JOURNAL OF THE Confederation OF INDIAN INDUSTRY 2 | February 2009 Communiqué Padma Vibhushan award winner Ashok S Ganguly Member, Prime Minister’s Council on Trade & Industry, Member India USA CEO Council, Member, Investment Commission, and Member, National Knowledge Commission Padma Bhushan award winners Shekhar Gupta A M Naik Sam Pitroda C K Prahalad Editor-in-Chief, Indian Chairman and Chairman, National Paul and Ruth McCracken Express Newspapers Managing Director, Knowledge Commission Distinguished University (Mumbai) Ltd. Larsen & Toubro Professor of Strategy Padma Shri award winner R K Krishnakumar Director, Tata Sons, Chairman, Tata Coffee & Asian Coffee, and Vice-Chairman, Tata Tea & Indian Hotels Communiqué February 2009 | 5 newsmaker event 4th Biennial Global Narendra Modi, Chief Minister, Gujarat, Mukesh Ambani, Chairman, Investors’ Summit 2009 Reliance Industries, Ratan Tata, Chairman, Tata Group, K V Kamath, President, CII, and Raila Amolo Odinga, Prime Minister, Kenya ibrant Gujarat, the 4th biennial Global Investors’ and Mr Ajit Gulabchand, Chairman & Managing Director, Summit 2009 brought together business leaders, Hindustan Construction Company Ltd, among several investors, corporations, thought leaders, policy other dignitaries. -

To Read/Download Press Note

Joint Press Note by Women and Human Rights' Organisation Jaipur, 17th September, 2013 We women and Human rights organisations of Rajasthan condemn in no uncertain terms, the slanderous arguments provided by Senior Advocate Ram Jethmalani in the Rajasthan High Court, Jodhpur, while arguing that bail be granted to child sexual abuser and assaulter Asaram. AS highlighted by the media, presenting arguments that the girl (victim) was afflicted with a chronic disease, "which draws a woman to a man", is violative of the law, as stating sexual histories and indulging in character assassination is not permitted. Indulging in such vile and slanderous arguments against a woman during rape matters and in this case a minor shows the low level to which the even senior lawyers of his stature can stoop too in order to influence the court. The Women's groups will write to the Bar Council of India against this slander so that Mr.Jethmalani be debarred from arguing in court, unless he apologise. We are, Renuka Pamecha (Women's Rehabilitation group), Kavita Srivastava ( People's Union for Civil Liberties, Rajasthan), Kusum Saiwal & Sumitra Chopra ( Rajasthan Janwadi Mahila Samiti), Mamta Jaitly (Vividha: Women's Documentation and Resource Centre), Nisha Sidhu ( National Federation of Indian Women, Rajasthan), Pawan Suran & Dr. Malti Gupta( Rajasthan University Women's Association), Komal Srivastava ( Bharat Gyan Vigyan Samiti), Mewa Bharti (Domestic Workers Union, Rajasthan), Nishat Hussein ( National Muslim Women Welfare Society), Asha Kalra (Women's Cell, State Employees Union), Vijay Lakshmi Joshi (People's Union for Civil Liberties, Bharat ( Vishakha: Women's Education & Resource Centre), Dr.