University of Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Fragmentation in Conflict and Its Impact on Prospects for Peace

oslo FORUM papers N°006 - December 2016 Understanding fragmentation in conflict and its impact on prospects for peace Kathleen Gallagher Cunningham www.hd centre.org – www.osloforum.org Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue 114, Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva | Switzerland t : +41 22 908 11 30 f : +41 22 908 11 40 [email protected] www.hdcentre.org Oslo Forum www.osloforum.org The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD) is a private diplo- macy organisation founded on the principles of humanity, impartiality and independence. Its mission is to help pre- vent, mitigate, and resolve armed conflict through dialogue and mediation. © 2016 – Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue Reproduction of all or part of this publication may be author- ised only with written consent and acknowledgment of the source. Kathleen Gallagher Cunningham Associate Professor at the Department of Government and Politics, University of Maryland [email protected] http://www.kathleengallaghercunningham.com Table of contents INTRODUCTION 2 1. WHAT IS FRAGMENTATION? 3 Fragmented actors 3 Multiple actors 3 Identifying fragmentation 4 New trends 4 The causes of fragmentation 5 2. THE CONSEQUENCES OF FRAGMENTATION FOR CONFLICT 7 Violence 7 Accommodation and war termination 7 Side switching 8 3. HOW PEACE PROCESSES AFFECT FRAGMENTATION 9 Coalescing 9 Intentional fragmentation 9 Unintentional fragmentation 9 Mediation 10 4. RESPONSES OF MEDIATORS AND OTHER THIRD-PARTY ACTORS TO FRAGMENTATION 11 Negotiations including all armed groups 11 Sequential negotiations 11 Inclusion of unarmed actors and national dialogue 12 Efforts to coalesce the opposition 13 5. AFTER SETTLEMENT 14 CONCLUSION 15 ENDNOTES 16 2 The Oslo Forum Papers | Understanding fragmentation in conflict Introduction Complicated conflicts with many disparate actors have cators of fragmentation, new trends, and a summation of why become increasingly common in the international system. -

Famine and Foreigners: Ethiopia Since Live Aid This Page Intentionally Left Blank Famine and Foreigners: Ethiopia Since Live Aid

‘Th ank God for great journalism. Th is book is a much needed, ex- haustively researched and eff ortlessly well written recent history of Ethiopia. A book that strips away the cant and rumour, the pros and antis and thoroughly explains the people, politics and economics of that most beautiful nation. A superb and vital piece of work by some- one who clearly loves the country of which he writes.’ Bob Geldof ‘Th e great Ethiopian famine changed everything and nothing. It fun- damentally altered the rich world’s sense of its responsibility to the hungry and the poor, but didn’t solve anything. A quarter of a century on, we’re still arguing about the roots of the problem, let alone the so- lution, and—though there has been progress—Ethiopia’s food inse- curity gets worse, not better. Peter Gill was one of the most thorough and eff ective television journalists of his generation. He was there in 1984 and his work at the time added up to the most sensible, balanced and comprehensive explanation of what had happened. Twenty-fi ve years later, he’s gone back to test decades of aspiration against the re- alities on the ground. It’s a book that bridges journalism and history, judicious analysis with a strong, and often gripping, narrative. Always readable, but never glib, this is a must for all those who think there is a simple answer to the famine, still waiting in the wings. ’ Michael Buerk ‘No outsider understands Ethiopia better than Peter Gill. He com- bines compassion with a clinical commitment to the truth. -

Title of Thesis: ABSTRACT CLASSIFYING BIAS

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis Directed By: Dr. David Zajic, Ph.D. Our project extends previous algorithmic approaches to finding bias in large text corpora. We used multilingual topic modeling to examine language-specific bias in the English, Spanish, and Russian versions of Wikipedia. In particular, we placed Spanish articles discussing the Cold War on a Russian-English viewpoint spectrum based on similarity in topic distribution. We then crowdsourced human annotations of Spanish Wikipedia articles for comparison to the topic model. Our hypothesis was that human annotators and topic modeling algorithms would provide correlated results for bias. However, that was not the case. Our annotators indicated that humans were more perceptive of sentiment in article text than topic distribution, which suggests that our classifier provides a different perspective on a text’s bias. CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Gemstone Honors Program, University of Maryland, 2018 Advisory Committee: Dr. David Zajic, Chair Dr. Brian Butler Dr. Marine Carpuat Dr. Melanie Kill Dr. Philip Resnik Mr. Ed Summers © Copyright by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang 2018 Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to our mentor, Dr. -

Dissertation Prospectus 21 June 2006 The

Dissertation Prospectus 21 June 2006 The Politics of Denial and Apology: Why Some States Apologize for Mass Killings while Others Do Not1 Motivating Puzzles and Research Questions The Politics of Denial and Apology From the decimation of the Herero population in German Southwest Africa to the Holocaust to more contemporary cases such as the al Anfal campaign against Iraqi Kurds in the late 1980s and the mass killing of civilians that is now taking place in the Darfur region of Sudan, the norm against mass killing has been repeatedly violated throughout this century. However, instead of a uniform pattern of admission and apology in the wake of such violations, the actual responses of perpetrator states to their own past violations of the norm against mass killing have varied tremendously. At one extreme, the Turkish government has consistently denied the perpetration of genocide against Armenian citizens in the Ottoman Empire during World War I.2 On the other extreme, Germany has fully admitted responsibility and apologized for the Holocaust. In between these two extremes of apology and denial are states such as Japan, which has only partially admitted culpability in the ‘Rape of Nanjing.’3 In addition to this variation in perpetrator states’ responses to their own violations, a cursory glance at these states’ experiences reveals that a range of different (and sometimes inconsistent) factors has provided the impetus that has led to change in some of these states’ policies. For example, while regime change led to policies that acknowledged the events of the Cambodian genocide and the Rwandan genocide in those two countries, a similar case of regime change in Turkey shortly after the Armenian genocide led to a policy of denial. -

A Long War Looming in Ethiopia Should Prompt Urgent U.S. Diplomacy Joshua Meservey

ISSUE BRIEF No. 6029 | NOVEMBER 23, 2020 DOUGLAS AND SARAH ALLISON CENTER FOR FOREIGN POLICY A Long War Looming in Ethiopia Should Prompt Urgent U.S. Diplomacy Joshua Meservey nascent civil war in Ethiopia threatens KEY TAKEAWAYS crisis and instability in the strategically A important East Africa region. The fight- A nascent civil war in Ethiopia threat- ing broke out after years of escalating tensions ens crisis in the strategically important between the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front East Africa region. (TPLF) that dominated the previous government, and the current government led by Prime Minis- ter Abiy Ahmed. The Abiy government believes it can score a quick The conflict is deepening the ethnic divides and mistrust of the government and decisive victory, but a prolonged insurgency is that cripple the country. likely. The conflict has already exacerbated the ethnic and political tensions in the country that cause divi- sion and violence; the U.S. should urgently organize The U.S. must lead concerned partners concerned countries to pressure the combatants to to press for a negotiated settlement negotiate, while also offering assistance and encour- before the fighting settles into a pro- agement for a longer-term plan for reconciliation tracted conflict. inside the country. This paper, in its entirety, can be found at http://report.heritage.org/ib6029 The Heritage Foundation | 214 Massachusetts Avenue, NE | Washington, DC 20002 | (202) 546-4400 | heritage.org Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of The Heritage Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before Congress. -

Abstract Political Science Smith Ii

ABSTRACT POLITICAL SCIENCE SMITH II, HOWARD C. B.A. Lane College, 2004 M.A. Arkansas State University, 2005 PUBLIC DIPLOMACY: THE UNITED STATES INFORMATION AGENCY (USIA) UTILIZING THE VOICE OF AMERICA AS FOREIGN POLICY IN ETHIOPIA (197 1- 1991). Committee Chair: R. Benneson DeJanes, Ph.D. Dissertation dated May 2012 The United States Information Agency played a significant role in spreading political education throughout Ethiopia by using the Voice of America’s broadcast. The USIA communicated the United States’ “anti-communist ideals” during the Cold War era in foreign nations. The research explains how the Voice of America broadcast in Ethiopia was a form of political education used to assist in the overthrow of Mengistu Haile Mariam. The dissertation aims to: 1. Define political education and the use of this technique by government agencies to achieve specific foreign policy goals. 2. Explain the threat to American foreign policy during 1971-1991 that caused the USIA and VOA to pursue an anti-Communist agenda in Ethiopia. 3. Express the influence political education has as a diplomatic strategy in transitioning Ethiopia from fascist communism to democratization. 4. Encourage heads of state and policy makers to realize the great influence political education can have on foreign policy, if applied via the proper methodology. PUBLIC DIPLOMACY: THE UNITED STATES INFORMATION AGENCY (USIA) UTILIZING THE VOICE OF AMERICA AS FOREIGN POLICY IN ETHIOPIA (1971-1991) A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CLARK ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY: HOWARD C. SMITH II DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE ATLANTA, GEORGIA MAY2012 ©20 12 HOWARD C. -

Honour List 2018 © International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY), 2018

HONOUR LIST 2018 © International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY), 2018 IBBY Secretariat Nonnenweg 12, Postfach CH-4009 Basel, Switzerland Tel. [int. +4161] 272 29 17 Fax [int. +4161] 272 27 57 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.ibby.org Book selection and documentation: IBBY National Sections Editors: Susan Dewhirst, Liz Page and Luzmaria Stauffenegger Design and Cover: Vischer Vettiger Hartmann, Basel Lithography: VVH, Basel Printing: China Children’s Press and Publication Group (CCPPG) Cover illustration: Motifs from nominated books (Nos. 16, 36, 54, 57, 73, 77, 81, 86, 102, www.ijb.de 104, 108, 109, 125 ) We wish to kindly thank the International Youth Library, Munich for their help with the Bibliographic data and subject headings, and the China Children’s Press and Publication Group for their generous sponsoring of the printing of this catalogue. IBBY Honour List 2018 IBBY Honour List 2018 The IBBY Honour List is a biennial selection of This activity is one of the most effective ways of We use standard British English for the spelling outstanding, recently published children’s books, furthering IBBY’s objective of encouraging inter- foreign names of people and places. Furthermore, honouring writers, illustrators and translators national understanding and cooperation through we have respected the way in which the nomi- from IBBY member countries. children’s literature. nees themselves spell their names in Latin letters. As a general rule, we have written published The 2018 Honour List comprises 191 nomina- An IBBY Honour List has been published every book titles in italics and, whenever possible, tions in 50 different languages from 61 countries. -

An Inter-State War in the Post-Cold War Era: Eritrea-Ethiopia (1998-2000)

LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE An Inter-state War in the Post-Cold War Era: Eritrea-Ethiopia (1998-2000) Alexandra Magnolia Dias A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Relations 2008 UMI Number: U501303 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U501303 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 v \& & > F 'SZV* AUTHOR DECLARATION I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Alexandra Magnolia Dias The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without prior consent of the author. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I understand that in the event of my thesis not being approved by the examiners, this declaration will become void. -

Untitleddocument

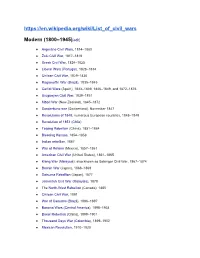

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_civil_wars Modern (1800–1945)[edit] ● Argentine Civil Wars, 1814–1880 ● Zulu Civil War, 1817–1819 ● Greek Civil War, 1824–1825 ● Liberal Wars (Portugal), 1828–1834. ● Chilean Civil War, 1829–1830 ● Ragamuffin War (Brazil), 1835–1845 ● Carlist Wars (Spain), 1833–1839, 1846–1849, and 1872–1876 ● Uruguayan Civil War, 1839–1851 ● Māori War (New Zealand), 1845–1872 ● Sonderbund war (Switzerland), November 1847 ● Revolutions of 1848; numerous European countries, 1848–1849 ● Revolution of 1851 (Chile) ● Taiping Rebellion (China), 1851–1864 ● Bleeding Kansas, 1854–1858 ● Indian rebellion, 1857 ● War of Reform (Mexico), 1857–1861 ● American Civil War (United States), 1861–1865 ● Klang War (Malaysia); also known as Selangor Civil War, 1867–1874 ● Boshin War (Japan), 1868–1869 ● Satsuma Rebellion (Japan), 1877 ● Jementah Civil War (Malaysia), 1878 ● The North-West Rebellion (Canada), 1885 ● Chilean Civil War, 1891 ● War of Canudos (Brazil), 1896–1897 ● Banana Wars (Central America), 1898–1934 ● Boxer Rebellion (China), 1899–1901 ● Thousand Days War (Colombia), 1899–1902 ● Mexican Revolution, 1910–1920 ● Warlord Era; period of civil wars between regional, provincial, and private armies in China, 1912–1928 ● Russian Civil War, 1917–1921 ● Iraqi–Kurdish conflict, 1918–2003 ● Finnish Civil War, 1918 ● German Revolution, 1918–1919 ● Irish Civil War, 1922–1923 ● Paraguayan Civil War, 1922–1923 ● Nicaraguan -

Reassessing Rebellion

Reassessing Rebellion: Exploring Recent Trends in Civil War Dynamics | i REASSESSING REBELLION EXPLORING RECENT TRENDS IN CIVIL WAR DYNAMICS An OEF Research Report REASSESSING REBELLION: Exploring Recent Trends in Civil War Dynamics Eric Keels Jay Benson John Filitz Joshua Lambert March 2019 http://dx.doi.org/10.18289/OEF.2019.035 ©Copyright One Earth Future 2019. All rights reserved Cover photo: Members of Jihadist group Hamza Abdualmuttalib train near Aleppo on July 19, 2012. Bulent Kilic/AFP/Getty Image Produced in cooperation with Human Security Report Project TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 01 Key Findings .........................................................................................................................................02 Summary of Policy Suggestions .............................................................................................................02 I. OVERVIEW ........................................................................................................................................ 03 Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................03 Stucture .................................................................................................................................................04 II. MODES OF WARFARE ..............................................................................................................05 -

Tigray People Liberation Front (TPLF)

Statement of Lauren Ploch Blanchard Specialist in African Affairs Before Committee on Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations U.S. House of Representatives Hearing on “The Unfolding Conflict in Ethiopia” December 1, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov TE10058 Congressional Research Service 1 Overview The outbreak of hostilities in Ethiopia’s Tigray region in November reflects a power struggle between the federal government of self-styled reformist Prime Minister Abiy (AH-bee) Ahmed and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), a former rebel movement that dominated Ethiopian politics for more than a quarter century before Abiy’s ascent to power in 2018.1 The conflict also highlights ethnic tensions in the country that have worsened in recent years amid political and economic reforms. The evolving conflict has already sparked atrocities, spurred refugee flows, and strained relations among countries in the region. The reported role of neighboring Eritrea in the hostilities heightens the risk of a wider conflict. After being hailed for his reforms and efforts to pursue peace at home and in the region, Abiy has faced growing criticism from some observers who express concern about democratic backsliding. By some accounts, the conflict in Tigray could undermine his standing and legacy.2 Some of Abiy’s early supporters have since become critics, accusing him of seeking to consolidate power, and some observers suggest his government has become increasingly intolerant of dissent and heavy-handed in its responses to law and order challenges.3 Abiy and his backers argue their actions are necessary to preserve order and avert further conflict. -

Civilian Police and Multinational Peacekeeping— a Workshop Series a Role for Democratic Policing

T O EN F J TM U R ST A I U.S. Department of Justice P C E E D B O J C S F A V M Office of Justice Programs F O I N A C I J S R E BJ G O OJJ DP O F PR National Institute of Justice JUSTICE Civilian Police and Multinational Peacekeeping— A Workshop Series A Role for Democratic Policing ➤ Research Forum Cosponsored by Center for Strategic and International Studies Police Executive Research Forum Washington, D.C., October 6, 1997 U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs 810 Seventh Street N.W. Washington, DC 20531 Janet Reno Attorney General Raymond C. Fisher Associate Attorney General Laurie Robinson Assistant Attorney General Noël Brennan Deputy Assistant Attorney General Jeremy Travis Director, National Institute of Justice Office of Justice Programs National Institute of Justice World Wide Web Site World Wide Web Site http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/nij National Institute of Justice Civilian Police and Multinational Peacekeeping— A Workshop Series A Role for Democratic Policing ➤ James Burack William Lewis Edward Marks Workshop Directors Washington, D.C., October 6, 1997 Cosponsored by the Center for Strategic and International Studies and the Police Executive Research Forum January 1999 NCJ 172842 Jeremy Travis Director James Finckenauer Marvene O’Rourke Program Monitors The Professional Conference Series of the National Institute of Justice supports a variety of live, researcher-practitioner exchanges, such as conferences, workshops, planning and development meetings, and similar support to the criminal justice field. The Research Forum publication series was designed to share information from these forums with a larger audience.