The Family Cyprinidae (Carps)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carp, Bighead (Hypophthalmichthys Nobilis)

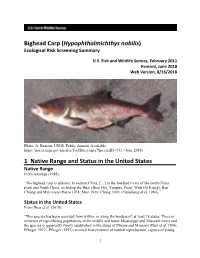

Bighead Carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis) Ecological Risk Screening Summary U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, February 2011 Revised, June 2018 Web Version, 8/16/2018 Photo: A. Benson, USGS. Public domain. Available: https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?SpeciesID=551. (June 2018). 1 Native Range and Status in the United States Native Range From Jennings (1988): “The bighead carp is endemic to eastern China, […] in the lowland rivers of the north China plain and South China, including the Huai (Huai Ho), Yangtze, Pearl, West (Si Kiang), Han Chiang and Min rivers (Herre 1934; Mori 1936; Chang 1966; Chunsheng et al. 1980).” Status in the United States From Nico et al. (2018): “This species has been recorded from within, or along the borders of, at least 18 states. There is evidence of reproducing populations in the middle and lower Mississippi and Missouri rivers and the species is apparently firmly established in the states of Illinois and Missouri (Burr et al. 1996; Pflieger 1997). Pflieger (1997) received first evidence of natural reproduction, capture of young 1 bighead carp, in Missouri in 1989. Burr and Warren (1993) reported on the taking of a postlarval fish in southern Illinois in 1992. Subsequently, Burr et al. (1996) noted that bighead carp appeared to be using the lower reaches of the Big Muddy, Cache, and Kaskaskia rivers in Illinois as spawning areas. Tucker et al. (1996) also found young-of-the-year in their 1992 and 1994 collections in the Mississippi River of Illinois and Missouri. Douglas et al. (1996) collected more than 1600 larvae of this genus from a backwater outlet of the Black River in Louisiana in 1994. -

Pathogen Susceptibility of Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys Molitrix) and Bighead Carp (Hypophthalmichthys Nobilis) in the Wabash River Watershed

Pathogen Susceptibility of Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) and Bighead Carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis) in the Wabash River Watershed FINAL REPORT Kensey Thurner PhD Student Maria S Sepúlveda, Reuben Goforth, Cecon Mahapatra Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907 Jon Amberg, US Geological Service, Upper Midwest Environmental Sciences Center, La Crosse, WI 54603 Eric Leis, US Fish and Widlife Service, La Crosse Fish Health Center, Onalaska, WI 54650 9/22/2014 Silver Carp (top) and Bighead Carp (bottom) caught in the Tippecanoe River, Photos by Alison Coulter Final Report 9/22/2014 - Page 2 Executive Summary The Pathogen Susceptibility of Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) and Bighead Carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis) in the Wabash River Watershed project was undertaken to address the lack of available information regarding pathogens in the highly invasive Silver and Bighead Carps, collectively known as bigheaded carps. Very little is known about the prevalence and effects of parasites, bacteria and viruses on the health of invasive bigheaded carp populations in the United States or the effects of bigheaded carps on the disease risk profile for sympatric, native fish of the U.S. The main objectives of this project were to conduct a systematic survey of parasites, bacteria and viruses of Asian carps and a representative number of native Indiana fish species in the upper and middle Wabash and the lower Tippecanoe Rivers, Indiana; to determine the susceptibility of Asian carps to a representative number of natural pathogens using in vitro approaches; and to involve anglers in the development of a cost effective state-wide surveillance program for documentation of viral diseases of fish. -

Review of Wetland and Aquatic Ecosystem in the Lower Mekong River Basin of Cambodia

FINAL REPORT Review of Wetland and Aquatic Ecosystem in the Lower Mekong River Basin of Cambodia By Kol Vathana Department of Nature Conservation and Protection Ministry of Environment Phnom Penh, Kingdom of Cambodia Submitted to The Cambodian National Mekong Committee Secretariat (CNMCS) and THE MEKONG RIVER COMMISSION SECRETARIAT (MRCS) August 2003 1 TABLE OF CONTENT I. INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................6 II. WETLAND BIODIVERSITY ..............................................................................................9 2.1 Current Status...................................................................................................................9 2.2 Ecosystem Diversity ........................................................................................................9 2.2.1 Freshwater Ecosystem ..............................................................................................9 2.2.2 Coastal and Marine Ecosystem...............................................................................12 2.3 Species Diversity ...........................................................................................................15 2.3.1 Fauna.......................................................................................................................15 2.3.2 Flora ........................................................................................................................19 2.4 Genetic Diversity ...........................................................................................................20 -

Cambodian Journal of Natural History

Cambodian Journal of Natural History Artisanal Fisheries Tiger Beetles & Herpetofauna Coral Reefs & Seagrass Meadows June 2019 Vol. 2019 No. 1 Cambodian Journal of Natural History Editors Email: [email protected], [email protected] • Dr Neil M. Furey, Chief Editor, Fauna & Flora International, Cambodia. • Dr Jenny C. Daltry, Senior Conservation Biologist, Fauna & Flora International, UK. • Dr Nicholas J. Souter, Mekong Case Study Manager, Conservation International, Cambodia. • Dr Ith Saveng, Project Manager, University Capacity Building Project, Fauna & Flora International, Cambodia. International Editorial Board • Dr Alison Behie, Australia National University, • Dr Keo Omaliss, Forestry Administration, Cambodia. Australia. • Ms Meas Seanghun, Royal University of Phnom Penh, • Dr Stephen J. Browne, Fauna & Flora International, Cambodia. UK. • Dr Ou Chouly, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State • Dr Chet Chealy, Royal University of Phnom Penh, University, USA. Cambodia. • Dr Nophea Sasaki, Asian Institute of Technology, • Mr Chhin Sophea, Ministry of Environment, Cambodia. Thailand. • Dr Martin Fisher, Editor of Oryx – The International • Dr Sok Serey, Royal University of Phnom Penh, Journal of Conservation, UK. Cambodia. • Dr Thomas N.E. Gray, Wildlife Alliance, Cambodia. • Dr Bryan L. Stuart, North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, USA. • Mr Khou Eang Hourt, National Authority for Preah Vihear, Cambodia. • Dr Sor Ratha, Ghent University, Belgium. Cover image: Chinese water dragon Physignathus cocincinus (© Jeremy Holden). The occurrence of this species and other herpetofauna in Phnom Kulen National Park is described in this issue by Geissler et al. (pages 40–63). News 1 News Save Cambodia’s Wildlife launches new project to New Master of Science in protect forest and biodiversity Sustainable Agriculture in Cambodia Agriculture forms the backbone of the Cambodian Between January 2019 and December 2022, Save Cambo- economy and is a priority sector in government policy. -

Hypophthalmichthys Molitrix and H. Nobilis)

carpsAB_covers 6/30/15 9:33 AM Page 1 BIGHEADED CARPS (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix and H. nobilis) An Annotated Bibliography on Literature Composed from 1970 to 2014 Extension Service Forest and Wildlife Research Center The information given here is for educational purposes only. References to commercial products, trade names, or suppliers are made with the understanding that no endorsement is implied and that no discrimination against other products or suppliers is intended. Copyright 2015 by Mississippi State University. All rights reserved. This publication may be copied and distributed without alteration for nonprofit educational purposes provided that credit is given to the Mississippi State University Extension Service. By Andrew Smith, Extension Associate Biologist, MSU Center for Resolving Human-Wildlife Conflicts. We are an equal opportunity employer, and all qualified applicants will receive consideration for employment without regard to race, color, religion, sex, Compiled by Andrew L. Smith national origin, disability status, protected veteran status, or any other characteristic protected by law. Edited by Steve Miranda, PhD, and Wes Neal, PhD Publication 2890 Extension Service of Mississippi State University, cooperating with U.S. Department of Agriculture. Published in furtherance of Acts of Congress, May 8 and June 30, 1914. GARY B. JACKSON, Director (500-06-15) carpsAB_covers 6/30/15 9:33 AM Page 3 Bigheaded Carps (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix and H. nobilis): An Annotated Bibliography on Literature Composed from 1970 to 2014 Compiled by Andrew L. Smith Mississippi State University Extension Service Center for Resolving Human-Wildlife Conflicts Department of Wildlife, Fisheries, and Aquaculture Forest and Wildlife Research Center Edited by Steve Miranda, PhD Wes Neal, PhD Andrew L. -

Carps, Minnows Etc. the Cyprinidae Is One of the Largest Fish Families With

SOF text final l/out 12/12/02 12:16 PM Page 60 4.2.2 Family Cyprinidae: Carps, Minnows etc. The Cyprinidae is one of the largest fish families with more than 1700 species world-wide. There are no native cyprinids in Australia. A number of cyprinids have been widely introduced to other parts of the world with four species in four genera which have been introduced to Australia. There are two species found in the ACT and surrounding area, Carp and Goldfish. Common Name: Goldfish Scientific Name: Carassius auratus Linnaeus 1758 Other Common Names: Common Carp, Crucian Carp, Prussian Carp, Other Scientific Names: None Usual wild colour. Photo: N. Armstrong Biology and Habitat Goldfish are usually associated with warm, slow-flowing lowland rivers or lakes. They are often found in association with aquatic vegetation. Goldfish spawn during summer with fish maturing at 100–150 mm length. Eggs are laid amongst aquatic plants and hatch in about one week. The diet includes small crustaceans, aquatic insect larvae, plant material and detritus. Goldfish in the Canberra region are often heavily infected with the parasitic copepod Lernaea sp. A consignment of Goldfish from Japan to Victoria is believed to be responsible for introducing to Australia the disease ‘Goldfish ulcer’, which also affects salmonid species such as trout. Apart from the introduction of this disease, the species is generally regarded as a ‘benign’ introduction to Australia, with little or no adverse impacts documented. 60 Fish in the Upper Murrumbidgee Catchment: A Review of Current Knowledge SOF text final l/out 12/12/02 12:16 PM Page 61 Distribution, Abundance and Evidence of Change Goldfish are native to eastern Asia and were first introduced into Australia in the 1860s when it was imported as an ornamental fish. -

Bighead Carp US ARMY CORPS of ENGINEERS Building Strong®

bighead carp US ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS Building Strong® Common Name bighead carp Genus & Species Hypophthalmichthys nobilis Family Cyprinidae (minnows and carps) Order Cypriniformes (carps, minnows, loaches, suckers) Class Actinopterygii (ray-finned fishes) Diagnosis: The bighead carp is characterized by a stout body, large head, massive opercles (gill covers), the head and opercles have no scales, snout bluntly rounded, mouth terminal and appears to be upside down, barbels are absent, and the jaws have no teeth. The eyes are small, located far forward below the angle of the jaw and project downward. Scales are small, cycloid, and cover the entire body. The lateral line is complete with 95-120 scales in series. This fish can weigh up to 100-lbs. The bighead carp may be distinguished from the silver carp by having long thread-like gill rakers, wheras silver carp have sponge like gill rakers. The keeled abdomen of the silver carp extends from the anal vent almost to the base of the head, whereas the keel of the bighead carp extends from the anal vent to the base of the pectoral fins. Ecology: This fish tends not to spawn in still water or small streams, but in large flood swollen rivers. Spawning occurs after spring rains have flooded the rivers and when the temperature of the water reaches 77°F. Eggs are fertilized externally and need to float downstream. Regarded as a filter-feeder, consuming mainly zooplankton, this fish is capable of eating between 20 and 120% of its body weight each day. Like all planktivores, they eat from the bottom of the food chain, thusly competing with native planktivores, juvenile fishes and mussels. -

Extraction and Characterisation of Pepsin-Solubilised Collagen from Fins, Scales, Skins, Bones and Swim Bladders of Bighead Carp

Food Chemistry xxx (2012) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Food Chemistry journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foodchem Extraction and characterisation of pepsin-solubilised collagen from fins, scales, skins, bones and swim bladders of bighead carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis) ⇑ Dasong Liu a, Li Liang a, Joe M. Regenstein b, Peng Zhou a, a State Key Laboratory of Food Science and Technology, School of Food Science and Technology, Jiangnan University, Wuxi, Jiangsu Province 214122, China b Department of Food Science, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853-7201, USA article info abstract Article history: The objective of this study was to extract and characterise pepsin-solubilised collagens (PSC) from the Received 26 September 2011 fins, scales, skins, bones and swim bladders of bighead carp and to provide a simultaneous comparison Received in revised form 15 December 2011 of five different sources from one species. The PSC were mainly characterised as type I collagen, contain- Accepted 7 February 2012 ing two a-chains, and each maintained their triple helical structure well. The thermostability of PSC from Available online xxxx the internal tissues (swim bladders and bones) was slightly higher than that of PSC from the external tissues (fins, scales and skins). The peptide hydrolysis patterns of all PSC digests using the V8 protease Keywords: were similar. All PSC were soluble at acidic pH (1–6) and lost their solubility at NaCl concentrations above Collagen 30 g/l. The resulting PSC from the five tissues would all be potentially useful commercially. Pepsin Bighead carp Ó 2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Fins Scales Skins Bones Swim bladders V8 protease 1. -

Bighead Carp, Hypophthalmichthys Nobilis

Invasive Species Fact Sheet Bighead carp, Hypophthalmichthys nobilis General Description Bighead carp are large, freshwater fish belonging to the minnow family. They are deep bodied and laterally compressed, with a large head that is nearly a 1/3 of the size of their body. Their eyes sit low on their head and they have a large, upturned mouth. Bighead carp are gray to silver on their back and sides with numerous grayish-black blotches, and cream Bighead carp colored on their bellies. Bighead carp have long, thin, Photo by South Dakota Department of Game, Fish, and Parks unfused gills that they use to filter feed zooplankton (animal plankton) and large phytoplankton (plant plankton) from the water. Bighead carp can grow over 4 feet in length and weigh up to 88 pounds. Bighead carp closely resemble silver carp, but can be distinguished by their blotchy coloration and unfused gills. Current Distribution Bighead carp are not currently found in California, but were previously introduced in 1989 when 3 ponds in Tehama County were illegally stocked with both bighead and grass carp. The California Department of Fish and Game eradicated all carp from the ponds in 1992. Bighead carp were first introduced to the United States in the 1970s. They have been reported within or along the borders of at least 18 central and southern states, and are established and reproducing in various waterbodies throughout those states, including the lower Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. Bighead carp are native to low gradient Pacific Ocean drainages in eastern Asia, from southern China through the northern edge of North Korea and into far eastern Russia. -

Resolving Cypriniformes Relationships Using an Anchored Enrichment Approach Carla C

Stout et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology (2016) 16:244 DOI 10.1186/s12862-016-0819-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Resolving Cypriniformes relationships using an anchored enrichment approach Carla C. Stout1*†, Milton Tan1†, Alan R. Lemmon2, Emily Moriarty Lemmon3 and Jonathan W. Armbruster1 Abstract Background: Cypriniformes (minnows, carps, loaches, and suckers) is the largest group of freshwater fishes in the world (~4300 described species). Despite much attention, previous attempts to elucidate relationships using molecular and morphological characters have been incongruent. In this study we present the first phylogenomic analysis using anchored hybrid enrichment for 172 taxa to represent the order (plus three out-group taxa), which is the largest dataset for the order to date (219 loci, 315,288 bp, average locus length of 1011 bp). Results: Concatenation analysis establishes a robust tree with 97 % of nodes at 100 % bootstrap support. Species tree analysis was highly congruent with the concatenation analysis with only two major differences: monophyly of Cobitoidei and placement of Danionidae. Conclusions: Most major clades obtained in prior molecular studies were validated as monophyletic, and we provide robust resolution for the relationships among these clades for the first time. These relationships can be used as a framework for addressing a variety of evolutionary questions (e.g. phylogeography, polyploidization, diversification, trait evolution, comparative genomics) for which Cypriniformes is ideally suited. Keywords: Fish, High-throughput -

Species Composition and Invasion Risks of Alien Ornamental Freshwater

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Species composition and invasion risks of alien ornamental freshwater fshes from pet stores in Klang Valley, Malaysia Abdulwakil Olawale Saba1,2, Ahmad Ismail1, Syaizwan Zahmir Zulkifi1, Muhammad Rasul Abdullah Halim3, Noor Azrizal Abdul Wahid4 & Mohammad Noor Azmai Amal1* The ornamental fsh trade has been considered as one of the most important routes of invasive alien fsh introduction into native freshwater ecosystems. Therefore, the species composition and invasion risks of fsh species from 60 freshwater fsh pet stores in Klang Valley, Malaysia were studied. A checklist of taxa belonging to 18 orders, 53 families, and 251 species of alien fshes was documented. Fish Invasiveness Screening Test (FIST) showed that seven (30.43%), eight (34.78%) and eight (34.78%) species were considered to be high, medium and low invasion risks, respectively. After the calibration of the Fish Invasiveness Screening Kit (FISK) v2 using the Receiver Operating Characteristics, a threshold value of 17 for distinguishing between invasive and non-invasive fshes was identifed. As a result, nine species (39.13%) were of high invasion risk. In this study, we found that non-native fshes dominated (85.66%) the freshwater ornamental trade in Klang Valley, while FISK is a more robust tool in assessing the risk of invasion, and for the most part, its outcome was commensurate with FIST. This study, for the frst time, revealed the number of high-risk ornamental fsh species that give an awareness of possible future invasion if unmonitored in Klang Valley, Malaysia. As a global hobby, fshkeeping is cherished by both young and old people. -

ANS Pocket Guide

Aquatic Nuisance Species SECOND Pocket Guide EDITION Table of Contents Introduction . 1 Prevention . 2 Laws and Regulations . 5 Take Action! . 11 Animals Mollusks . 12 Crustaceans . 16 Amphibians . 22 Fish . 28 Plants Algae . 70 Submerged . 74 Emergent . 94 Floating . 102 Riparian . 116 Pathogens . 124 Index . 130 Resources . 140 COVER PHOTOs (Clockwise from top): AMERIcaN BULLFROG BY CARL D. HOWE; EURASIAN WaTERMILFOIL BY JOSEPH DITOMASO, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA DAVIS; PIRANHA BY WIKIMEDIA; QUAGGA MUSSELS BY MICHAEL PORTER, U.S. ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS WRITTEN BY WENDY HaNOPHY Printed on recycled paper Introduction What are Aquatic Nuisance Species? Aquatic nuisance species (ANS) are invasive animals, plants, and disease-causing pathogens that are “out of place” in Colorado’s rivers, lakes, streams, and wetlands . They are introduced accidentally or intentionally outside of their native range . Because they are not native to Colorado habitats, they have no natural competitors and predators . Without these checks and balances, the invaders are able to reproduce rapidly and out-compete native species . ANS have harmful effects on natural resources and our use of them . Aquatic Nuisance Species are Everyone’s Problem ANS damage Colorado’s lands and waters, hurt the economy, ruin recreation opportunities, and threaten public health . Many ANS consume enormous amounts of water and reduce the water supply for livestock, wildlife, and humans . They impede water distribution systems for municipal, industrial, and agricultural supplies . They can damage boats and fishing equipment and impair all forms of water based recreation . These species change the physical characteristics of bodies of water and alter food chains . As habitat is destroyed by invasive species, the wildlife that depends on it disappears as well .