Carp, Bighead (Hypophthalmichthys Nobilis)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bighead Carp Are Coming from Asia and Swimming up the Mississippi River, and the Bighead Carp Coming up the Minnesota River

Where they are mostly hiding out? Bighead Carp Invaders Invasive species: The Bighead carp are coming from Asia and swimming up the Mississippi River, and The Bighead Carp coming up the Minnesota River. (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis) This is an emergency to the pubic about the invasive Bighead carp. Recent research says that these invaders are taking a big toll on the ecosystem. “Why?” some people asked. Read on to learn more. How can you get rid of them? Carp Taco Recipe Serbian Carp Recipe EAT THEM!!!!! • 1 pound ground carp • 2 pounds carp Carp Taco Recipe • 3 tablespoons veggie oil • ¼ pound butter • 1 package taco seasoning • 2 finely chopped onions • 1/2 cup water • Sliced tomato or salsa • 3 tablespoons tomato paste • 12 flour tortillas • ¼ pound chopped mushrooms • Shredded lettuce • Salt • Grated cheddar cheese • Red pepper • Taco sauce • Flour • Sour cream • Water Roll carp in flour seasoned with salt Before shredding the fish, remove the mud vain, or reddish-brown section of and red Pepper. Sear in butter. After Serbian Carp Recipe the fish. Cook the shredded fish in the oil removing carp, sauté onions and until its color changes. Add the taco mushrooms. Add tomato paste and a seasonings and water. Cook until nearly little water. Put carp in and stew until dry, stirring occasionally. Heat tortilla in well done. a deep fry pan, turning them brown on both sides. They should still be soft and pliable when warm. Fill each tortilla with fish. Add the rest of the ingredients, and top it with sour cream. . -

Disease List for Aquaculture Health Certificate

Quarantine Standard for Designated Species of Imported/Exported Aquatic Animals [Attached Table] 4. Listed Diseases & Quarantine Standard for Designated Species Listed disease designated species standard Common name Disease Pathogen 1. Epizootic haematopoietic Epizootic Perca fluviatilis Redfin perch necrosis(EHN) haematopoietic Oncorhynchus mykiss Rainbow trout necrosis virus(EHNV) Macquaria australasica Macquarie perch Bidyanus bidyanus Silver perch Gambusia affinis Mosquito fish Galaxias olidus Mountain galaxias Negative Maccullochella peelii Murray cod Salmo salar Atlantic salmon Ameirus melas Black bullhead Esox lucius Pike 2. Spring viraemia of Spring viraemia of Cyprinus carpio Common carp carp, (SVC) carp virus(SVCV) Grass carp, Ctenopharyngodon idella white amur Hypophthalmichthys molitrix Silver carp Hypophthalmichthys nobilis Bighead carp Carassius carassius Crucian carp Carassius auratus Goldfish Tinca tinca Tench Sheatfish, Silurus glanis European catfish, wels Negative Leuciscus idus Orfe Rutilus rutilus Roach Danio rerio Zebrafish Esox lucius Northern pike Poecilia reticulata Guppy Lepomis gibbosus Pumpkinseed Oncorhynchus mykiss Rainbow trout Abramis brama Freshwater bream Notemigonus cysoleucas Golden shiner 3.Viral haemorrhagic Viral haemorrhagic Oncorhynchus spp. Pacific salmon septicaemia(VHS) septicaemia Oncorhynchus mykiss Rainbow trout virus(VHSV) Gadus macrocephalus Pacific cod Aulorhynchus flavidus Tubesnout Cymatogaster aggregata Shiner perch Ammodytes hexapterus Pacific sandlance Merluccius productus Pacific -

Forecasting the Impacts of Silver and Bighead Carp on the Lake Erie Food Web

Transactions of the American Fisheries Society ISSN: 0002-8487 (Print) 1548-8659 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/utaf20 Forecasting the Impacts of Silver and Bighead Carp on the Lake Erie Food Web Hongyan Zhang, Edward S. Rutherford, Doran M. Mason, Jason T. Breck, Marion E. Wittmann, Roger M. Cooke, David M. Lodge, John D. Rothlisberger, Xinhua Zhu & Timothy B. Johnson To cite this article: Hongyan Zhang, Edward S. Rutherford, Doran M. Mason, Jason T. Breck, Marion E. Wittmann, Roger M. Cooke, David M. Lodge, John D. Rothlisberger, Xinhua Zhu & Timothy B. Johnson (2016) Forecasting the Impacts of Silver and Bighead Carp on the Lake Erie Food Web, Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, 145:1, 136-162, DOI: 10.1080/00028487.2015.1069211 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00028487.2015.1069211 © 2016 The Author(s). Published with View supplementary material license by American Fisheries Society© Hongyan Zhang, Edward S. Rutherford, Doran M. Mason, Jason T. Breck, Marion E. Wittmann, Roger M. Cooke, David M. Lodge, Published online: 30 Dec 2015. Submit your article to this journal John D. Rothlisberger, Xinhua Zhu, Timothy B. Johnson Article views: 1095 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=utaf20 Download by: [University of Strathclyde] Date: 02 March 2016, At: 02:30 Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 145:136–162, 2016 Published with license by American Fisheries Society 2016 ISSN: 0002-8487 print / 1548-8659 online DOI: 10.1080/00028487.2015.1069211 ARTICLE Forecasting the Impacts of Silver and Bighead Carp on the Lake Erie Food Web Hongyan Zhang* Cooperative Institute for Limnology and Ecosystems Research, School of Natural Resources and Environment, University of Michigan, 4840 South State Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48108, USA Edward S. -

Fish Species of Saskatchewan

Introduction From the shallow, nutrient -rich potholes of the prairies to the clear, cool rock -lined waters of our province’s north, Saskatchewan can boast over 50,000 fish-bearing bodies of water. Indeed, water accounts for about one-eighth, or 80,000 square kilometers, of this province’s total surface area. As numerous and varied as these waterbodies are, so too are the types of fish that inhabit them. In total, Saskatchewan is home to 67 different fish species from 16 separate taxonomic families. Of these 67, 58 are native to Saskatchewan while the remaining nine represent species that have either been introduced to our waters or have naturally extended their range into the province. Approximately one-third of the fish species found within Saskatchewan can be classed as sportfish. These are the fish commonly sought out by anglers and are the best known. The remaining two-thirds can be grouped as minnow or rough-fish species. The focus of this booklet is primarily on the sportfish of Saskatchewan, but it also includes information about several rough-fish species as well. Descriptions provide information regarding the appearance of particular fish as well as habitat preferences and spawning and feeding behaviours. The individual species range maps are subject to change due to natural range extensions and recessions or because of changes in fisheries management. "...I shall stay him no longer than to wish him a rainy evening to read this following Discourse; and that, if he be an honest Angler, the east wind may never blow when he goes a -fishing." The Compleat Angler Izaak Walton, 1593-1683 This booklet was originally published by the Saskatchewan Watershed Authority with funds generated from the sale of angling licences and made available through the FISH AND WILDLIFE DEVELOPMENT FUND. -

Aging Techniques & Population Dynamics of Blue Suckers (Cycleptus Elongatus) in the Lower Wabash River

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications Summer 2020 Aging Techniques & Population Dynamics of Blue Suckers (Cycleptus elongatus) in the Lower Wabash River Dakota S. Radford Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons Recommended Citation Radford, Dakota S., "Aging Techniques & Population Dynamics of Blue Suckers (Cycleptus elongatus) in the Lower Wabash River" (2020). Masters Theses. 4806. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/4806 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AGING TECHNIQUES & POPULATION DYNAMICS OF BLUE SUCKERS (CYCLEPTUS ELONGATUS) IN THE LOWER WABASH RIVER By Dakota S. Radford B.S. Environmental Biology Eastern Illinois University A thesis prepared for the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Biological Sciences Eastern Illinois University May 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Thesis abstract .................................................................................................................... iii Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ iv List of Tables .......................................................................................................................v -

Chinese Fish Price Report Issue 2/2020 Issue 2/2020 Chinese Fish Price Report

Chinese Fish Price Report Issue 2/2020 Issue 2/2020 Chinese Fish Price Report The Chinese Fish Price Report Editorial Board Editor in Chief Audun Lem Marcio Castro de Souza John Ryder Marcio Castro de Souza Contributing Editors Coordinator Maria Catalano Weiwei Wang Helga Josupeit William Griffin Contributing Partner Graphic Designer China Aquatic Products Processing and Alessia Capasso Marketing Alliance (CAPPMA) EDITORIAL OFFICE GLOBEFISH Products, Trade and Marketing Branch (NFIM) Fisheries Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Viale delle Terme di Caracalla 00153 Rome, Italy Tel. +39 06 5705 57227 E-mail: [email protected] www.globefish.org REGIONAL OFFICES Latin America, Caribbean Africa Arab Countries INFOPESCA, Casilla de Correo 7086, INFOPÊCHE, BP 1747 Abidjan 01, INFOSAMAK, 71, Boulevard Rahal, Julio Herrea y Obes 1296, 11200 Côte d’Ivoire El Meskini Casablanda 20 000, Morocco Montevideo, Uruguay Tel: (225) 20 21 31 98/20 21 57 75 Tel: (212) 522540856 Tel: (598) 2 9028701/29028702 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (212) 522540855 Fax: (598) 2 9030501 [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.infopeche.ci [email protected] Website: www.infopesca.org Website: www.infosamak.org Europe Asia China Eurofish, H.C. Andersens Boulevard 44-46, INFOFISH INFOYU, Room 901, No 18, Maizidian street, 1553 Copenhagen V, Denmark 1st Floor, Wisma LKIM Jalan Desaria Chaoyang District, Beijing 100125, China Tel: (+45) 333777dd Pulau Meranti, 47120 Puchong, Selangor DE -

Pathogen Susceptibility of Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys Molitrix) and Bighead Carp (Hypophthalmichthys Nobilis) in the Wabash River Watershed

Pathogen Susceptibility of Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) and Bighead Carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis) in the Wabash River Watershed FINAL REPORT Kensey Thurner PhD Student Maria S Sepúlveda, Reuben Goforth, Cecon Mahapatra Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907 Jon Amberg, US Geological Service, Upper Midwest Environmental Sciences Center, La Crosse, WI 54603 Eric Leis, US Fish and Widlife Service, La Crosse Fish Health Center, Onalaska, WI 54650 9/22/2014 Silver Carp (top) and Bighead Carp (bottom) caught in the Tippecanoe River, Photos by Alison Coulter Final Report 9/22/2014 - Page 2 Executive Summary The Pathogen Susceptibility of Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) and Bighead Carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis) in the Wabash River Watershed project was undertaken to address the lack of available information regarding pathogens in the highly invasive Silver and Bighead Carps, collectively known as bigheaded carps. Very little is known about the prevalence and effects of parasites, bacteria and viruses on the health of invasive bigheaded carp populations in the United States or the effects of bigheaded carps on the disease risk profile for sympatric, native fish of the U.S. The main objectives of this project were to conduct a systematic survey of parasites, bacteria and viruses of Asian carps and a representative number of native Indiana fish species in the upper and middle Wabash and the lower Tippecanoe Rivers, Indiana; to determine the susceptibility of Asian carps to a representative number of natural pathogens using in vitro approaches; and to involve anglers in the development of a cost effective state-wide surveillance program for documentation of viral diseases of fish. -

Habitat Alterations and Fish Assemblage Structure in the Missouri River System, USA: Is Ecomorphology an Explanation?

TRANSACTIONS OF THE KANSAS Vol. 121, no. 1-2 ACADEMY OF SCIENCE p. 1 - 22 (2018) Habitat alterations and fish assemblage structure in the Missouri River system, USA: Is ecomorphology an explanation? TIM L. WELKER1 AND DENNIS L. SCARNECCHIA2 Department of Fish and Wildlife Sciences, University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho; 1. Present Address: U. S. Army Corps of Engineers, Yankton, South Dakota; 2. Corresponding author [email protected] Sampling was conducted over a two-year period to determine if fish body morphology (as indicated by the Fineness Ratio (FR), an index of fish streamlining) and habitat alterations can interact to influence fish assemblage structure in three human-altered segments of the Missouri River. It was hypothesized that segments with more variability in depths, velocities, and substrates would have a fish assemblage characterized by more diversity in streamlining. Conversely, it was hypothesized that fish assemblages in more altered river segments would exhibit less diversity in streamlining, i.e., less variability from optimal values because of more uniform habitat conditions. In faster more uniform habitats, fewer variations from optimal streamlining would be adaptive. The three flowing segments studied encompassed the mouth of the Yellowstone River (YSS; moderately altered), the area below Garrison Dam, North Dakota (GOS; below dam-highly altered) and the segment from St. Joseph to Kansas City, Missouri (SKS; channelized-highly altered). The three segments exhibited greatly different fish assemblages. Small native minnows (Cyprinidae), particularly flathead chub (Platygobio gracilis), and deep-bodied suckers, such as bigmouth buffalo (Ictiobus cyprinellus), were common in the YSS. The GOS was dominated by the dorsally compressed fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas). -

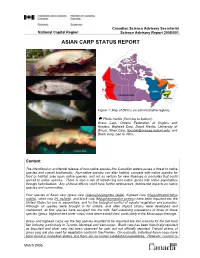

Asian Carp Status Report

Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat National Capital Region Science Advisory Report 2005/001 ASIAN CARP STATUS REPORT Figure 1: Map of DFO’s six administrative regions. § Photo credits (from top to bottom): Grass Carp, Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters; Bighead Carp, David Riecks, University of Illinois; Silver Carp, [email protected]; and Black Carp, Leo G. Nico. Context The intentional or accidental release of non-native species into Canadian waters poses a threat to native species and overall biodiversity. Non-native species can alter habitat, compete with native species for food or habitat, prey upon native species, and act as vectors for new diseases or parasites that could spread to native species. There is also a risk of introducing non-native genes into native populations through hybridisation. Any of these effects could have further widespread, detrimental impacts on native species and communities. Four species of Asian carp (grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella), bighead carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis), silver carp (H. molitrix), and black carp (Mylopharyngodon piceus)) have been imported into the United States for use in aquaculture, and for the biological control of aquatic vegetation and parasites. Although all species were brought in for culture, and often triploid strains were developed and maintained, all four species have escaped into the wild. Self-sustaining populations of three of these species (grass, bighead and silver carps) have been established, particularly in the Mississippi drainage. Grass and bighead carps are the two species reported to be imported live into Canada for the live food fish industry, particularly in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver. Black carp has been historically reported as imported and silver carp has been observed for sale, but not officially reported. -

Hypophthalmichthys Molitrix and H. Nobilis)

carpsAB_covers 6/30/15 9:33 AM Page 1 BIGHEADED CARPS (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix and H. nobilis) An Annotated Bibliography on Literature Composed from 1970 to 2014 Extension Service Forest and Wildlife Research Center The information given here is for educational purposes only. References to commercial products, trade names, or suppliers are made with the understanding that no endorsement is implied and that no discrimination against other products or suppliers is intended. Copyright 2015 by Mississippi State University. All rights reserved. This publication may be copied and distributed without alteration for nonprofit educational purposes provided that credit is given to the Mississippi State University Extension Service. By Andrew Smith, Extension Associate Biologist, MSU Center for Resolving Human-Wildlife Conflicts. We are an equal opportunity employer, and all qualified applicants will receive consideration for employment without regard to race, color, religion, sex, Compiled by Andrew L. Smith national origin, disability status, protected veteran status, or any other characteristic protected by law. Edited by Steve Miranda, PhD, and Wes Neal, PhD Publication 2890 Extension Service of Mississippi State University, cooperating with U.S. Department of Agriculture. Published in furtherance of Acts of Congress, May 8 and June 30, 1914. GARY B. JACKSON, Director (500-06-15) carpsAB_covers 6/30/15 9:33 AM Page 3 Bigheaded Carps (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix and H. nobilis): An Annotated Bibliography on Literature Composed from 1970 to 2014 Compiled by Andrew L. Smith Mississippi State University Extension Service Center for Resolving Human-Wildlife Conflicts Department of Wildlife, Fisheries, and Aquaculture Forest and Wildlife Research Center Edited by Steve Miranda, PhD Wes Neal, PhD Andrew L. -

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4—An Update April 2013 Prepared by: Pam L. Fuller, Amy J. Benson, and Matthew J. Cannister U.S. Geological Survey Southeast Ecological Science Center Gainesville, Florida Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Cover Photos: Silver Carp, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix – Auburn University Giant Applesnail, Pomacea maculata – David Knott Straightedge Crayfish, Procambarus hayi – U.S. Forest Service i Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ v List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................ vi INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Overview of Region 4 Introductions Since 2000 ....................................................................................... 1 Format of Species Accounts ...................................................................................................................... 2 Explanation of Maps ................................................................................................................................ -

Carps, Minnows Etc. the Cyprinidae Is One of the Largest Fish Families With

SOF text final l/out 12/12/02 12:16 PM Page 60 4.2.2 Family Cyprinidae: Carps, Minnows etc. The Cyprinidae is one of the largest fish families with more than 1700 species world-wide. There are no native cyprinids in Australia. A number of cyprinids have been widely introduced to other parts of the world with four species in four genera which have been introduced to Australia. There are two species found in the ACT and surrounding area, Carp and Goldfish. Common Name: Goldfish Scientific Name: Carassius auratus Linnaeus 1758 Other Common Names: Common Carp, Crucian Carp, Prussian Carp, Other Scientific Names: None Usual wild colour. Photo: N. Armstrong Biology and Habitat Goldfish are usually associated with warm, slow-flowing lowland rivers or lakes. They are often found in association with aquatic vegetation. Goldfish spawn during summer with fish maturing at 100–150 mm length. Eggs are laid amongst aquatic plants and hatch in about one week. The diet includes small crustaceans, aquatic insect larvae, plant material and detritus. Goldfish in the Canberra region are often heavily infected with the parasitic copepod Lernaea sp. A consignment of Goldfish from Japan to Victoria is believed to be responsible for introducing to Australia the disease ‘Goldfish ulcer’, which also affects salmonid species such as trout. Apart from the introduction of this disease, the species is generally regarded as a ‘benign’ introduction to Australia, with little or no adverse impacts documented. 60 Fish in the Upper Murrumbidgee Catchment: A Review of Current Knowledge SOF text final l/out 12/12/02 12:16 PM Page 61 Distribution, Abundance and Evidence of Change Goldfish are native to eastern Asia and were first introduced into Australia in the 1860s when it was imported as an ornamental fish.