Gabriel M. Leung and John Bacon Shone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Record of Proceedings

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 3 November 2010 1399 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 3 November 2010 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. 1400 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 3 November 2010 THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TIMOTHY FOK TSUN-TING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. -

The Hippocratic Dilemmas Guanxi and Professional Work in Hospital Care in China

China Perspectives 2016/4 | 2016 The Health System and Access to Healthcare in China The Hippocratic Dilemmas Guanxi and Professional Work in Hospital Care in China Longwen Fu and Cheris Shun-Ching Chan Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/7091 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 December 2016 Number of pages: 19-27 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Longwen Fu and Cheris Shun-Ching Chan, « The Hippocratic Dilemmas », China Perspectives [Online], 2016/4 | 2016, Online since 01 December 2017, connection on 28 October 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/7091 © All rights reserved Special feature China perspectives The Hippocratic Dilemmas Guanxi and Professional Work in Hospital Care in China LONGWEN FU AND CHERIS SHUN-CHING CHAN ABSTRACT: Patients mobilising guanxi (interpersonal relations) to gain access to hospital care is prevalent in post-Mao China. Yet few studies have centred on how medical professionals deal with guanxi patients. Based on ethnographic research and applying an analytical frame of Chi - nese guanxi developed by Fei Xiaotong (1992 [1948]) and Cheris Shun-ching Chan (2009), this article examines the dilemmas that Chinese phy - sicians face in weighing professional standards versus guanxi . We divide the patients into three general categories: patients without any guanxi , patients with weak to moderate ties with physicians, and patients with strong ties with physicians. We find that physicians face few di - lemmas when they interact with patients without guanxi . They largely adhere to their professional code of practice and generally display do - minance over the patients. -

Monthly Report HK

January 2011 in Hong Kong 31.1.2011 / No 85 A condensed press review prepared by the Consulate General of Switzerland in HK Economy + Finance HK still ranked world's freest economy: HK remains the world’s freest economy for the 17th straight year and ranked 1st out of 41 countries – according to a report released by the Heritage Foundation and the Wall Street Journal. The city’s score remains unchanged from last year at 89.7 out of 100 in the 2011 Index of Economic Freedom, with small declines in the score for government spending and labour freedom offsetting improvements in fiscal freedom, monetary freedom, and freedom from corruption. The report said HK is one of the world’s most competitive financial and business centres, demonstrating a high degree of resilience during the global financial crisis. City casts off shadow of global financial crisis: HK's economy is rebounding from the aftermath of the global financial crisis, with the public coffers enjoying the first eight-month surplus in three years. The latest announcement showed a far better financial picture than the government had forecast. In his budget speech in February, Financial Secretary John Tsang projected a net deficit of HK$25.2 billion for the current financial year. However, consensus estimates among most accounting firms now put the full financial year budget at a surplus of at least HK$60 billion. The reserves stood at HK$537 billion as of November 30, compared to HK$455.5 billion a year earlier. HK jobless rate falls to 4pc: HK's unemployment rate declined from 4.1 per cent in September to November last year to 4.0 per cent in October to December last year. -

View Latest Version Here. the Challenge Of

This transcript was exported on Jul 02, 2020 - view latest version here. Steven Goldstein: Good morning, good afternoon, good evening, wherever you are. My name is Steven Goldstein and I'm the director of the Taiwan Workshop at the Fairbank Center at Harvard University. And I'm very pleased today to moderate a round table on the COVID-19 virus and the experience in Taiwan. Let me just start off with a few thoughts. Taiwan appears to be the land of miracles. In the 1970s, when I was a grad... well, I was more than a graduate student, the Taiwan miracle was the economic transformation that took place in Taiwan, after the establishment of rule on the Island. In the two thousands, or in the turn of the 20th century, the Taiwan miracle was a political miracle. It was the democratization of an authoritarian regime. Steven Goldstein: And now people are talking of a third miracle Taiwan's response to the COVID-19 virus. You see the more I read about it, the more I see terms like gold standard being used to characterize the Taiwan experience. Miracle's not a good word, because every one of those miracles, including the miracle today has been the result of political leadership and societal participation. They're the result of policies led by political leaders with the participation and cooperation of the people. This was unquestionably the case in the first two miracles. And today it's becoming increasingly clear that the same holds for the present miracle. Political leadership, societal effort, combined with technological capabilities, social policies, government institutions have all played central roles in Taiwan's response. -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 11

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 11 May 2011 10073 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 11 May 2011 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. 10074 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 11 May 2011 THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE AUDREY EU YUET-MEE, S.C., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 17

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 17 November 2010 2033 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 17 November 2010 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. 2034 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 17 November 2010 THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TIMOTHY FOK TSUN-TING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE AUDREY EU YUET-MEE, S.C., J.P. -

Report Are Those of the Authors and Do Not Necessarily Represent the Opinions of Civic Exchange

Hong Kong’s Budget: Challenges and Solutions for the Longer Term Tony Latter Leo Goodstadt Roger Nissim February 2009 www.civic-exchange.org Civic Exchange Room 701, Hoseinee House, 69 Wyndham Street, Central, Hong Kong. Tel: (852) 2893 0213 Fax: (852) 3105 9713 Civic Exchange is a non-profit organisation that helps to improve policy and decision making through research and analysis. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinions of Civic Exchange. Preface The government’s budget is a political document. It provides financial resources for the achievement of government policies. Irrespective of high sounding commitments, the resources set aside for them indicate the degree of seriousness. How the government views what it will, and can, afford to fund is bound up with its philosophy on budgetary issues. Much of this philosophy has not changed for decades. What is particularly noteworthy is the lack of debate about the underlying assumptions behind the government’s philosophy. Even though there are contending views in society, as can be seen from the many criticisms of government policies and frequent acrimonious exchanges between officials and legislators, there has been little serious, sustained deliberation and debate about the policies and financing of long-term issues, such as those relating to demographic changes and the public services needed to meet them. This publication is Civic Exchange’s contribution to that much needed debate. We hope this will be useful to government officials, legislators, political parties, students and members of the public who have an interest in local affairs. -

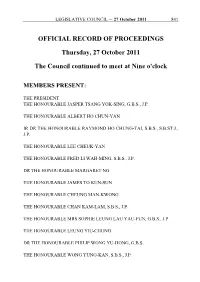

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 27

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 27 October 2011 841 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 27 October 2011 The Council continued to meet at Nine o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. 842 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 27 October 2011 THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TIMOTHY FOK TSUN-TING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE AUDREY EU YUET-MEE, S.C., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, M.H. THE HONOURABLE LEE WING-TAT DR THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P. -

香港特別行政區排名名單 the Precedence List of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

二零二一年九月 September 2021 香港特別行政區排名名單 THE PRECEDENCE LIST OF THE HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION 1. 行政長官 林鄭月娥女士,大紫荊勳賢,GBS The Chief Executive The Hon Mrs Carrie LAM CHENG Yuet-ngor, GBM, GBS 2. 終審法院首席法官 張舉能首席法官,大紫荊勳賢 The Chief Justice of the Court of Final The Hon Andrew CHEUNG Kui-nung, Appeal GBM 3. 香港特別行政區前任行政長官(見註一) Former Chief Executives of the HKSAR (See Note 1) 董建華先生,大紫荊勳賢 The Hon TUNG Chee Hwa, GBM 曾蔭權先生,大紫荊勳賢 The Hon Donald TSANG, GBM 梁振英先生,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP The Hon C Y LEUNG, GBM, GBS, JP 4. 政務司司長 李家超先生,SBS, PDSM, JP The Chief Secretary for Administration The Hon John LEE Ka-chiu, SBS, PDSM, JP 5. 財政司司長 陳茂波先生,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, MH, JP The Financial Secretary The Hon Paul CHAN Mo-po, GBM, GBS, MH, JP 6. 律政司司長 鄭若驊女士,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, SC, JP The Secretary for Justice The Hon Teresa CHENG Yeuk-wah, GBM, GBS, SC, JP 7. 立法會主席 梁君彥議員,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP The President of the Legislative Council The Hon Andrew LEUNG Kwan-yuen, GBM, GBS, JP - 2 - 行政會議非官守議員召集人 陳智思議員,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP The Convenor of the Non-official The Hon Bernard Charnwut CHAN, Members of the Executive Council GBM, GBS, JP 其他行政會議成員 Other Members of the Executive Council 史美倫議員,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP The Hon Mrs Laura CHA SHIH May-lung, GBM, GBS, JP 李國章議員,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP Prof the Hon Arthur LI Kwok-cheung, GBM, GBS, JP 周松崗議員,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP The Hon CHOW Chung-kong, GBM, GBS, JP 羅范椒芬議員,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP The Hon Mrs Fanny LAW FAN Chiu-fun, GBM, GBS, JP 黃錦星議員,GBS, JP 環境局局長 The Hon WONG Kam-sing, GBS, JP Secretary for the Environment # 林健鋒議員,GBS, JP The Hon Jeffrey LAM Kin-fung, GBS, JP 葉國謙議員,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP The Hon -

Communications, the Media and Information Technology

350 Chapter 17 Communications, the Media and Information Technology Hong Kong people are among the most informed in the world, thanks to the city’s enterprising news media and telecommunications industry. There are currently close to 700 daily newspapers and periodicals published in Hong Kong. More than 86 per cent of households are broadband service subscribers, while mobile subscriber penetration is over 210 per cent. Hong Kong has one of the most successful telecommunications markets in the world. The market is fully liberalised and highly competitive, providing a wide range of innovative and advanced telecommunications services at reasonable prices to consumers and business users. It has a vibrant broadcasting industry offering a wide range of services to the community and is also one of the world’s major film production centres, while through its Digital 21 Strategy, the Commerce and Economic Development Bureau strives to establish Hong Kong as a leading digital economy. The Mass Media Hong Kong’s mass media at the end of 2011 included 50 daily newspapers (including a number of electronic newspapers), 651 periodicals, two domestic free television programme service licensees, three domestic pay television programme service licensees, 17 non-domestic television programme service licensees, one government funded public service broadcaster and four sound broadcasting licensees. The availability of the latest telecommunications technology and keen interest in Hong Kong’s affairs have attracted many international news agencies, newspapers with international readership and overseas broadcasting corporations to establish regional headquarters or representative offices here. The production of regional publications in Hong Kong underlines its importance as a financial, industrial, trading and communications centre. -

Dr. William Hsiao

Distinguished Achievement Citation William Hsiao Class of 1959 With this presentation of Ohio Wesleyan’s Distinguished Achievement Citation, the Ohio Wesleyan University Alumni Association Board of Directors is honored and privileged to recognize William Hsiao and his career as a public administrator, humanitarian, and professor. He is considered one of the world's foremost experts on health care economics and financing. His advice to leaders of state and government both here and abroad has changed the lives of millions of people across the world. A native of Beijing, Dr. Hsiao graduated from OWU in 1959 with a degree in Physics and Math. Following graduation, he worked as an actuary for the Connecticut General Life Insurance Company. In 1968, Dr. Hsiao became Deputy Chief Actuary for the Social Security Administration where he led two blue-ribbon panels regarding the actuarial viability of the Social Security System. He left government service in 1971 and entered the graduate program at Harvard University where he obtained a Master of Public Administration, Master of Arts, and Ph.D. in Economics in 1982. During his studies, he served as a consultant to the U.S. House and Senate on Social Security. Dr. Hsiao was appointed to the faculty of the Harvard School of Public Health as an Assistant Professor in 1979 and became a full professor in 1986. He currently serves as the K.T. Li Professor of Economics at the Harvard School of Public Health. Dr. Hsiao regularly advises U.S. government agencies, foreign governments, and non-governmental organizations such as the World Bank, UNICEF, and the World Health Organization. -

Mental Health Conference “Building a Better Mental Health System Through Engagement” 11/1/2014, 9:30A.M

Mental Health Conference “Building a better mental health system through engagement” 11/1/2014, 9:30a.m. – 4:30p.m. Hong Kong Mental Health Council Mental Health Council (HKMHC) is set up to pursue an integrated and harmony society by facilitating the government to develop a long-term and holistic mental health policy, with planning and coordination on man-power and resources to promote positive attitude of mental wellness. The council suggested the government to set up the Mental Health Commission to formulate, review and implement the mental health policy at Hong Kong, helping to enhance the mental wellness of Hong Kong citizens. In June 1982, a person with mental illness raided the pupils of a kindergarten at Un Chau Estate, resulting 6 deaths and 44 injuries. Over 30 years after the incident, similar incident hardly happened again, but incidents related to mental illness happened occasionally. Hong Kong citizens showed much concern on the situation of persons with mental illness as well as mental health services. The Disability Discrimination Ordinance came into effect in 1996 while the Mental Health Ordinance was amended in 1997. Apart from these 2 ordinances, there was neither a mental health policy nor a concrete policy objective for Hong Kong citizens. The rationale of Hong Kong’s mental health service was discovered to be left behind the western countries, in terms of driving, coordination and development of different mental health services under the absence of a comprehensive mental health policy, leading to the work of prevention, education, promotion and treatment half-done. In viewing of the problems, a group of stakeholders coming from different disciplines founded Hong Kong Mental Health Council, aiming at reviewing and driving the development of the Hong Kong’s mental health policy.