Field Notes from Alamuru Mandal in East Godavari District, A.P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Missing Person - Period Wise Report (CIS) 27/12/2019 Page 1 of 50

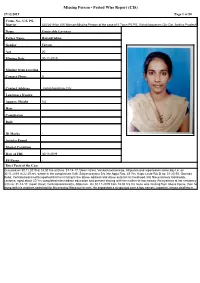

Missing Person - Period Wise Report (CIS) 27/12/2019 Page 1 of 50 Crime No., U/S, PS, Name District 420/2019 for U/S Woman-Missing Person of the case of II Town PS PS, Vishakhapatnam City Dst, Andhra Pradesh Name Ganireddy Lavanya Father Name Ramakrishna Gender Female Age 20 Age Missing Date 30-11-2019 Missing from Location Contact Phone 0 Contact Address Vishakhapatnam City Languages Known Approx. Height 5.0 Hair Complexion Built ID Marks - Articles Found Mental Condition Date of FIR 30/11/2019 PS Phone - Brief Facts of the Case Occurred on 30.11.2019 at 18.30 hrs at D.no: 31-14-17, Gowri street, Venkateswarametta, Allipuram and reported on same day I.e. on 30.11.2019 at 22.20 hrs, where in the complainant Valli. Satyanarayana S/o late Appa Rao, 43 Yrs, Kapu caste R/o D.no: 31-23-35, Govinda Road, Venkateswarametta reported that he is living in the above address and drove auto for his livelihood. His Niece namely Ganireddy. Lavanya, aged about 20 Yrs completed intermediate education and present staying with her mother-in-law namely Atchiyamma at her residency at D.no: 31-14-17, Gowri street, Venkateswarametta, Allipuram. On 30.11.2019 from 18.30 hrs his niece was missing from above house, then he along with his relatives searched for his missing Niece but-in-vain. He expressed a suspicious over a boy namely Jagadish, whose dwelling in 27/12/2019 Page 2 of 50 Crime No., U/S, PS, 246/2019 for U/S 366-A,354A,376 (2)(i),376(2)n,376(3)-IPC,4,12,11,5(1)-POCSO ACT 2012,Girl-Missing Person of Name District the case of Mandapeta Town PS, East Godavari Dst, Andhra Pradesh Name Bokka Gowthami Father Name Srinu Gender Female Age 16 Age Missing Date 30-11-2019 Missing from Location Vijnan College Mandapeta Contact Phone 0 Penikeru village,Penikeru village,Alamuru, East Godavari, Contact Address Andhra Pradesh Languages Known Approx. -

Kakinada Port

Oct 04 2021 (23:52) India Rail Info 1 Kakinada Port - Renigunta Express/17250 - Exp - SCR GDR/Gudur Junction to RU/Renigunta Junction 2h 5m - 83 km - 7 halts - Departs Daily # Code Station Name Arrives Avg Depart Avg Halt PF Day Km Spd Elv Zone s 1 COA Kakinada Port 13:55 0 1 0 14 5 SCR 2 CCT Kakinada Town Junction 14:03 14:05 2m 1 1 2 41 10 SCR 3 SLO Samalkot Junction 14:23 14:25 2m 3 1 14 67 17 SCR 4 MPU Medapadu 14:33 14:34 1m 0 1 23 71 20 SCR 5 BVL Bikkavolu 14:41 14:42 1m 1 1 31 66 19 SCR 6 BBPM Balabhadrapuram 14:45 14:46 1m 0 1 35 121 23 SCR 7 APT Anaparti 14:49 14:50 1m 0 1 41 45 19 SCR 8 DWP Dwarapudi 14:55 14:56 1m 0 1 44 60 18 SCR 9 RJY Rajahmundry 15:16 15:18 2m 1 1 64 39 23 SCR 10 KVR Kovvur 15:29 15:30 1m 2 1 72 67 SCR 11 NDD Nidadavolu Junction 15:43 15:45 2m 2 1 86 91 SCR 12 TDD Tadepalligudem 15:58 16:00 2m 3 1 106 96 SCR 13 CEL Chebrol 16:09 16:10 1m 3 1 120 78 SCR 14 PUA Pulla 16:16 16:17 1m 1 1 128 67 SCR 15 BMD Bhimadolu 16:23 16:24 1m 3 1 135 71 SCR 16 EE Eluru 16:40 16:42 2m 3 1 154 32 SCR 17 PRH Powerpet 16:45 16:46 1m 2 1 155 102 20 SCR 18 NZD Nuzvid 16:56 16:57 1m 0 1 172 82 28 SCR 19 TOU Telaprolu 17:04 17:05 1m 0 1 182 61 20 SCR 20 MBD Mustabada 17:23 17:25 2m 0 1 200 9 18 SCR 21 BZA Vijayawada Junction 18:55 19:05 10m 2,4 1 213 45 SCR 22 PVD Peddavadlapudi 19:21 19:22 1m 0 1 225 76 20 SCR 23 CLVR Chiluvur 19:25 19:26 1m 0 1 229 86 19 SCR 24 DIG Duggirala 19:30 19:31 1m 0 1 235 85 16 SCR 25 TEL Tenali Junction 19:38 19:40 2m 3 1 245 73 SCR 26 NDO Nidubrolu 19:58 20:00 2m 1 1 267 77 9 SCR 27 BPP Bapatla 20:16 -

Baseline St1udy Training in Sea Safety Development

BASELINE ST1UDY FOR TRAINING IN SEA SAFETY DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME IN EAST GODAVARI DISTRICT, ANDHRA. PRADESH NINA FOR FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANISATION OF TFIE UNITED NATIONS AND DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES, GOVTOF ANDHRAPRADESH BY ACTION FOR FOOD PRODUCTION (AFPRO) FIELD UNIT VI, HYDERABAD 1998 TRAINING IN SEA SAFETY DEVELOPIVIENT PROGRAMME IN EAST GODA VARI DISTRICT, ANDHRA PRADESH INDIA TCP/IND/6712 BASELINE STUDY November, 1997January, 1998 BY ACTION FOR FOOD PRODUCTION (AFPRO) FIELD UNIT VI, HYDERABAD 12-13-483/39, Street No.1, Tarnaka Secunderabad - 500 017 DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES, GOVT.OF ANDHRAPRADESH FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANISATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS The designations employed and the presentations of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Action for Food Production (AFPRO) Field Unit VI is grateful to the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) and the Department of Fisheries Andhra Pradesh for giving the opportunityfor conducting the Baseline Study - Training in Sea Safety Development Programme in East Godavari District, Andhra Pradesh. Action for Food Production (AFPRO) Field Unit VI wish to thank the following for all the assistance and cooperation extended during the study. The Fisherfolk and Sarpanches of Balusitippa, Bhairavapalem and other villages (Mansanitippa, Komaragiri, Joggampetta, Gadimoga, Peddavalsula). Mr.O. Bhavani Shankar,Additional Director and Conunisioner ofFisheries in Charge, Hyderabad. Mr.Ch.Krishna Murthy, Joint Director of Fisheries, Hyderabad. -

Abstracts Submitted for the World Rice Research Conference, Tokyo-Tsukuba, Japan, November 4-7, 2004

Abstracts submitted for the World Rice Research Conference, Tokyo-Tsukuba, Japan, November 4-7, 2004 A. Papers proposed for a panel with a focus on The System of Rice Intensification under the theme "Improving Rice Yield Potential". Note: the first paper is an overview paper, and the number of country reports is now fairly large, so the first paper could be a plenary paper; the country papers, and the stature of their authors, should assure people that SRI is 'for real.' • The System of Rice Intensification: Capitalizing on Existing Yield Potentials by Changing Management Practices to Increase Rice Productivity with Reduced Inputs and More Profitability, Norman Uphoff, Cornell International Institute for Food, Agriculture and Development, Cornell University, USA • The System of Rice Intensification: Evaluations in Andhra Pradesh, India, A. Satyanarayana, Director of Extension, A. N. G. Ranga Agricultural University, and P. V. Satyanarayana, Agricultural Research Station, Maruteru, Andhra Pradesh, India • On-Farm Evaluation of the System of Rice Intensification in Andhra Pradesh, India, P. V. Satyanarayana, T. Srinivas, Agricultural Research Station, Maruteru, West Godavari District, Andhra Pradesh, and A. Satyanarayana, Director of Extension, ANGRAU, India • On-Farm Evaluation of SRI in Tamiraparani Command Area, Tamil Nadu, India, T. M. Thiyagarajan, College of Agriculture, Killikulam, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, India • Opportunities for Rice Self-Sufficiency in Indonesia with the System of Rice Inensification, Anischan Gani, Indonesian Institute for Rice Research, Sukamandi, Indonesia • The 3-S Rice Cultivation Method Developed in Northern China: Comparisons with the System of Rice Intensification, Jin Xueyong, Northeastern Agricultural University, Haerbin, China • Diversifying Rice-Based Farming Systems in the Southern Philippines with the System of Rice Intensification, Felipe Rafols Jr., Allan Gayem, Ligaya Belarmino, Flor L. -

NAME of the POST: ST KAMATI Total Qualified Candidates

SC/ST BACKLOG RECRUITMENT-2018 NAME OF THE POST: ST KAMATI Total Qualified Candidates - 1186 ST KAMATI QUALIFIED LIST OF CANDIDATES Age points @ 0.8620 for every year Specific SNO APPLNO NAME of the Candidate MOBILE GENDER ADDRESS VILLAGE MANDAL DOB Age as on 31-07-2017 QUALIFICATION CASTE from "18" Remarks years onwards Telugu Reading 1 14801 KAMBHAM CHINNARAO 9491519539 M GONDOLU Gondolu Addateegala 24-08-1970 46 Years 11 Months 7 Days 24.14 and Writing ST NARAKONDA Vara Telugu Reading 2 723 SATYANARAYANA 9100644508 M H NO 1-42 Somulagudem Ramachandrapuram 10-10-1970 46 Years 9 Months 21 Days 24.14 and Writing ST Vara Telugu Reading 3 23858 KARAM VENKATAIAH 8790763549 M HNO 1-1 CHOPPALLI Choppalle Ramachandrapuram 05-01-1971 46 Years 6 Months 26 Days 24.14 and Writing ST Telugu Reading 4 10922 MATURI VENKATESWARLU 8106295174 M HNO 1-89/1 K N PURAM VILLAGE K.N.Puram Yetipaka 05-01-1971 46 Years 6 Months 26 Days 24.14 and Writing ST Vara Telugu Reading 5 35052 URMA CHANDRAIAH 9908144945 M H NO 1-60 Choppalle Ramachandrapuram 05-03-1971 46 Years 4 Months 26 Days 24.14 and Writing ST MOHANAPURAM VI MOHANAPURAM POST Telugu Reading 6 27682 GANTHA SOMAYYA 8500551226 M GANGAVARAM MANDALAM Mohanapuram Gangavaram 05-04-1971 46 Years 3 Months 26 Days 24.14 and Writing ST D NO 1-323 MAREDUMILLI Telugu Reading 7 14400 GORLE MOHAN RAO 9494887462 M CHELAKA VEEDHI PIN 533295 Maredumilli Maredumilli 15-05-1971 46 Years 2 Months 16 Days 24.14 and Writing ST VEERABATHULA Telugu Reading 8 27150 RATNARAJU 8985145329 M BARRIMAMIDI Barrimamidi Gangavaram 01-06-1971 -

International Paper Appm Limited Details of Unclaimed Dividend For

INTERNATIONAL PAPER APPM LIMITED DETAILS OF UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2009-10 AS ON 27.07.2016 PROPOSED DATE OF INVESTOR_FIRST INVESTOR_MIDD INVESTOR_LASTN FATHER/HUSBAND FATHER/HUSBAND FATHER/HUSBAND TRANSFER TO WARRAN NAME LE NAME AME FIRSTNAME MIDDLE NAME LAST NAME ADDRESS COUNTRY STATE DISTRICT PINCODE FOLIO DPID-CLIENTID INVESTMENT TYPE AMOUNT IEPF T NO Amount for SANCHETI GALLI, CHOTA BAZAR, unclaimed and SANDIP LAKHICHAND CHORDIA LAKHICHAND CHUNILAL CHORDIA MALKAPUR INDIA Maharashtra Buldhana 443101 OO-12010600-00354985 unpaid dividend 75 19-AUG-2017 2356 Amount for B-55 /1182, AZAD NAGER VEERA unclaimed and HIREN NARENDRA SHAH NARENDRA K SHAH DESAI, ANDHERI (W), MUMBAI INDIA Maharashtra Mumbai City 400058 OO-12010900-00402837 unpaid dividend 25 19-AUG-2017 7495 Amount for NO.12, THOLASINGAM STREET, unclaimed and MANORAMA DEVI MUNDHRA MANGILAL SOWCARPET, CHENNAI INDIA Tamil Nadu Chennai 600079 OO-12010900-01617625 unpaid dividend 30 19-AUG-2017 4826 PLOT NO 11 TELEPHONE Amount for EXCHANGE, ROAD PHASE 1 R K unclaimed and MANISH RAI GAYA PRASAD RAI NAGAR, BILASPUR, BILASPUR INDIA Chhattisgarh Bilaspur 495001 OO-12010900-01972124 unpaid dividend 250 19-AUG-2017 2491 Amount for unclaimed and PRAMOD KUMAR JAIN NEME CHAND JAIN 70 CENTRAL AVENUE, KOLKATA INDIA West Bengal Kolkata 700001 OO-12010900-02001771 unpaid dividend 50 19-AUG-2017 5113 Amount for unclaimed and AJAY PANDEY HUF SHRI RAJJULAL PANDEY 18 JUNI HATRI, RAJNANDGAON INDIA Chhattisgarh Rajnandgaon 491441 OO-12010900-02562027 unpaid dividend 50 19-AUG-2017 2475 Amount -

Content on E-Panchayat Mission Mode Project

Centre for Innovations in Public Systems (CIPS) (An Organization Established with Funding from Government of India) CIPS - Content on e-Panchayat Mission Mode Project Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................ 1 2. Project Conceptualization ................................................................................................................................................... 2 3. Objectives of e-Panchayat MMP ......................................................................................................................................... 3 4. Applications Developed Under e-Panchayat MMP ............................................................................................................. 4 5. Adoption Status of PES Applications in States/UTs ............................................................................................................ 6 6. State Specific Applications corresponding to PES Applications .......................................................................................... 8 7. State Wise - No. of Panchayats providing services electronically ..................................................................................... 33 8. Model Panchayats for implementation of PES / State specific applications .................................................................... 40 9. e-Taal - Standard Services of e-Panchayat ....................................................................................................................... -

Sealed Tenders Are Invited for Supply, Erection And

Aditya Global Business Incubator(AGBI) (Implementing Agency for Kadiyapulanka Coir Cluster ) Surampalem, Andhra Pradesh 533437, Mobile: 7396115809. Tender Notice N.I.T No. 6/Kadiyapulanka /2020 dt. 23.11.2020 Sealed Tenders are invited by Aditya Global Business Incubator , the Implementing Agency (IA) of Kadiyapulanka Coir Cluster, from reputed manufacturers / authorized dealers for the work mentioned below: Name of Work EMD Supply, erection and commissioning of The tender comprises of 5 packages: machineries, equipments and its S.No Package EMD (in Rs.) accessories for the Common Facility Center 1. Package I 52,000/- 2. Package II 62,700/- of Kadiyapulanka Coir Cluster on turnkey 3. Package IIIA 20,000/- basis under the Scheme of Fund for & IIIB Regeneration of Traditional Industries (SFURTI) of Coir Board, EMD in the form of Demand Draft drawn in Ministry of MSME, Government of India. favour of “Aditya Global Business Incubator ”, payable at SBI Chemudulanka. The tender Schedule can be downloaded at free of cost from the website www.coirboard.gov.in or upto 5.00 PM on 10.12.2020. The last date for submission of tenders is upto 05.00 PM on 10.12.2020 and the same will be opened on the next day 11.12.2020 at 11.00 AM. The tender document shall be submitted at the office of Coir Board Regional Office Main Rd, Alcot Gardens, Rajahmundry, Andhra Pradesh 533101 . 1 M/s. ADITYA GLOBAL BUSINESS INCUBATOR (Implementing Agency –Kadiyapulanka Coir Cluster, East Godavari District) Office: Surampalem, Andhra Pradesh 533437, Mobile: +91-7396115809, Email: [email protected] TENDER REFERENCE No. -

Appellant(S)/Complainant(S): Respondent(S): SURAPUREDDY DHANALAKSHMI CPIO : W/O SURAPUREDDY KAPU ALIAS 1

Hearing Notice Central Information Commission Baba Gang Nath Marg Munirka, New Delhi - 110067 01126181927 http://dsscic.nic.in/online-link-paper-compliance/add File No. CIC/ANDBK/A/2018/161707 DATE : 16-09-2020 NOTICE OF HEARING FOR APPEAL/COMPLAINT Appellant(s)/Complainant(s): Respondent(s): SURAPUREDDY DHANALAKSHMI CPIO : W/o SURAPUREDDY KAPU ALIAS 1. UNION BANK OF INDIA BRAHMADU, SANDHIPUDI VILLAGE, REGIONAL OFFICE - ALAMURU MANDAL, EAST GODAVARI KAKINADA, Katyayani Complex, DISTRICT, ANDHRA PRADESH - 533 232 2nd Floor, Opp. Appolo Andhra Pradesh,East Hospital, Kakinada, EAST Godavari,533232 GODAVARI (A.P.) - 533 001 (EARLIER ANDHRA BANK) Date of RTI Date of reply,if Date of 1st Appeal Date of order,if any,of CPIO made,if any any,of First AA 15-06-2018 04-07-2018 20-07-2018 20-08-2018 1. Take notice that the above appeal/complaint in respect of RTI application dated 15-06-2018 filed by the appellant/complainant has been listed for hearing before Hon'ble Information Commissioner Mr. Suresh Chandra at Venue VC Address on 14-10-2020 at 11:10 AM. 2. The appellant/complainant may present his/her case(s) in person or through his/her duly authorized representative. 3. (a) CPIO/PIO should personally attend the hearing; if for a compelling reason(s) he/she is unable to be present, he/she has to give reasons for the same and shall authorise an officer not below the rank of CPIO.PIO, fully acquainted with the facts of the case and bring complete file/file(s) with him. (b) If the CPIO attending the hearing before the Commission does not happen to be the concerned CPIO, it shall still be his/her responsibility to ensure that the CPIO(s) concerned must attend with complete file concerning the RTI request, the hearing along with him. -

Statistical Abstract of Andhra Pradesh 19 6 2

STATISTICAL ABSTRACT OF ANDHRA PRADESH 19 6 2 I ssu e d B y BUREAU OF ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS GOVERNMENT OF ANDHRA PRADESH HYDERABAD PREFACE The present issue of the Statistical Abstract of Andhra Pradesh is the seventh of its kind in the series and contains latest available data on various items of importance which have a bearing on the Economic Development of the State. I am sure that this publication will serve as a useful reference book in general and will be of immense use particularly to the Administrators and those engaged in Economic Planning and Development. One table on Houseless and Institutional Population and four tables relating to the results of the 15th Round, Socio Economic Survey, 1959-60 have been newly added to this issue. I thank the various Heads of Departments, both of the State and Central Governments, for their kind Co-operation in furnishing the data promptly. Any suggestions for the improvement of this Publication are most welcome. D. RANGA RAMANUJAM, DIRECTOR. Bureau of Economics and S tatistics, Hyderabad. 14th November, 1963 Abbreviations used: ... = nil or negligible N .A . = not available N.Q . = no quotation N .S. = no stock Kg. kilogram Q. quintal Km. = kilom etre Km2 = square kilometre M-’ = cubic metre Tonne metric ton N T E N T S T able N o, P ag es I Population 1. 1 Variation in population of Andhra Pr^dash, 1901 to 1961 ... l 1 . 2 Area, population and density of popul^tion-Districtwise, 1961 ... 2 1. 3 Area and population of Taluks, 1961 ... 3-8 1. -

Statistical Abstract Df Andhra Pradesh 19 61

STATISTICAL ABSTRACT DF ANDHRA PRADESH 19 61 ISSU ED BY BUREAU OF ECONOMICS AND STATISTTCS noVERNMENT OF ANDHRA PRADESH HYDERABAD PREF A C E The Statistical Abstract of Anihra Pradesh, 1961 is the sixth issue in the series and contains the latest a\iilable data relating to the important . aspects of economic and social develo»ment of the State. As usual the State figures have been given for a period of five years in all sectors and data in respect of districts is given for the Uest year. M etric units o f Weights and Measures have been adopted in this issue except under the heading “Agricultre”. Even in this category, metric equivalents have been given in the sunnary tables showing State data.. I thank the various Heads f Departments both of the State and Central Governments for their kind c.-operation in bringing out this publica tion with the minimum time-lag. Sggestions for any improvement of the publication are most welcome. D. RANGA RAMANUJAM DIRECTOR - Bureau o f Economics and Sta^sHc'^, Hyderabad, 22nd January, 1 9 0 ^ Abbreviations used: ... ” nil or negligible n. a. = not available n. q. = no quotation n. s. = no stock kg. = kilogram q- = quintal km. "= kilom etre km2 = square kilometre m3 = cubic metre tonne metric ton CONTENTS T a b l e N o. S u b je c t a n d L is t o f T a bles P a g e s /. Po pulation 1. 1 Variation in population of Andhra Pradesh, 1901 to 1961 ... 1 1. 2 Area, population and density of population-Districtwise, 1961 .. -

Meeseva Photos Quality-Aponline

Authorized Sl.No Address E Mail Phone No Quality District Agent Id Opp:Indian Bank,Kallur 1 USDP-CTCO [email protected] 9912048036 Good Road,Sodam,Chittoor-517123 Chittoor Akula Bazaar Street, Ramasamudram, [email protected] 2 APO-CTR-KER 9441330274 Good Chittoor-517417 .in Chittoor H.No.6-122-5,ThimmareddY 3 USDP-CTSO [email protected] 9441574209 Good Complex,Kalikiri,Chittoor-517234 Chittoor H.No.1-292, Main Raod, Kalakada, 4 USDP-CTSC [email protected] 9966940669 Good Chittoor-517236 Chittoor D.No: 27-47-15-3, Gokul Circle, padmaja.mahesh@gmai 5 USDP-CTMM 9866767928 Good Punganur,Chittoor-517247 l.com Chittoor Raja ReddY Complex, Opp: SBI, 6 USDP-CTJA [email protected] 9963165353 Good Polakala(V&P), Irala, Chittoor-517130 Chittoor D.No: 4-127/1, Bazaar Street, [email protected] 7 USDP-CTRA 9948947926 Good Rompichrela, Chittoor-517192 m Chittoor Near Bus Stand, Gangadhara Nellore, gnpreddY_rsdp_ctr@Ya 8 APO-CTR-GNP 9985192450 Good Chittoor-517125 hoo.co.in Chittoor C-64/4, MBT Road, Angallu, [email protected] 9 APO-CTR-ESM 9441573950 Good Kurabalakota Mandal, Chittoor-517325 o.in Chittoor Patrapalli [email protected] 10 USDP-CTNN 9052852280 Good Thanda,mittachittavaripalli,pungnur m Chittoor S/o G Sreenivasulu, Post Office Street, [email protected] 11 USDP-CTOS Rallabudugur(V&P), Shanthipuram 9550986909 Good om Mandal., Chittor-517423 Chittoor D.No: 8-119, Main Bazaar, Main Road, 12 USDP-CTRR [email protected] 9701594124 Good PeddamandYam, Chittoor-517297 Chittoor 13 USDP-CTSN K V Palli, Chitoor-517213 [email protected] 9052092803 Good Chittoor Shop No: 5, B P K N Complex, M B T venkatchalla_5@Yahoo.