HPV Microarrays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development and Maintenance of Epidermal Stem Cells in Skin Adnexa

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Development and Maintenance of Epidermal Stem Cells in Skin Adnexa Jaroslav Mokry * and Rishikaysh Pisal Medical Faculty, Charles University, 500 03 Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 30 October 2020; Accepted: 18 December 2020; Published: 20 December 2020 Abstract: The skin surface is modified by numerous appendages. These structures arise from epithelial stem cells (SCs) through the induction of epidermal placodes as a result of local signalling interplay with mesenchymal cells based on the Wnt–(Dkk4)–Eda–Shh cascade. Slight modifications of the cascade, with the participation of antagonistic signalling, decide whether multipotent epidermal SCs develop in interfollicular epidermis, scales, hair/feather follicles, nails or skin glands. This review describes the roles of epidermal SCs in the development of skin adnexa and interfollicular epidermis, as well as their maintenance. Each skin structure arises from distinct pools of epidermal SCs that are harboured in specific but different niches that control SC behaviour. Such relationships explain differences in marker and gene expression patterns between particular SC subsets. The activity of well-compartmentalized epidermal SCs is orchestrated with that of other skin cells not only along the hair cycle but also in the course of skin regeneration following injury. This review highlights several membrane markers, cytoplasmic proteins and transcription factors associated with epidermal SCs. Keywords: stem cell; epidermal placode; skin adnexa; signalling; hair pigmentation; markers; keratins 1. Epidermal Stem Cells as Units of Development 1.1. Development of the Epidermis and Placode Formation The embryonic skin at very early stages of development is covered by a surface ectoderm that is a precursor to the epidermis and its multiple derivatives. -

Alpha Actinin 4: an Intergral Component of Transcriptional

ALPHA ACTININ 4: AN INTERGRAL COMPONENT OF TRANSCRIPTIONAL PROGRAM REGULATED BY NUCLEAR HORMONE RECEPTORS By SIMRAN KHURANA Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy Thesis Advisor: Dr. Hung-Ying Kao Department of Biochemistry CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY August, 2011 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of SIMRAN KHURANA ______________________________________________________ PhD candidate for the ________________________________degree *. Dr. David Samols (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) Dr. Hung-Ying Kao ________________________________________________ Dr. Edward Stavnezer ________________________________________________ Dr. Leslie Bruggeman ________________________________________________ Dr. Colleen Croniger ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ May 2011 (date) _______________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES vii LIST OF FIGURES viii ACKNOWLEDEMENTS xii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS xiii ABSTRACT 1 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION Family of Nuclear Receptors 3 Mechanism of transcriptional regulation by co-repressors and co-activators 8 Importance of LXXLL motif of co-activators in NR mediated transcription 12 Cyclic recruitment of co-regulators on the target promoters 15 Actin and actin related proteins (ABPs) in transcription -

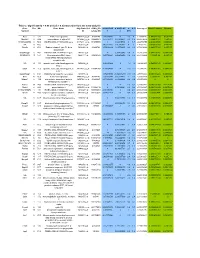

Table 2. Significant

Table 2. Significant (Q < 0.05 and |d | > 0.5) transcripts from the meta-analysis Gene Chr Mb Gene Name Affy ProbeSet cDNA_IDs d HAP/LAP d HAP/LAP d d IS Average d Ztest P values Q-value Symbol ID (study #5) 1 2 STS B2m 2 122 beta-2 microglobulin 1452428_a_at AI848245 1.75334941 4 3.2 4 3.2316485 1.07398E-09 5.69E-08 Man2b1 8 84.4 mannosidase 2, alpha B1 1416340_a_at H4049B01 3.75722111 3.87309653 2.1 1.6 2.84852656 5.32443E-07 1.58E-05 1110032A03Rik 9 50.9 RIKEN cDNA 1110032A03 gene 1417211_a_at H4035E05 4 1.66015788 4 1.7 2.82772795 2.94266E-05 0.000527 NA 9 48.5 --- 1456111_at 3.43701477 1.85785922 4 2 2.8237185 9.97969E-08 3.48E-06 Scn4b 9 45.3 Sodium channel, type IV, beta 1434008_at AI844796 3.79536664 1.63774235 3.3 2.3 2.75319499 1.48057E-08 6.21E-07 polypeptide Gadd45gip1 8 84.1 RIKEN cDNA 2310040G17 gene 1417619_at 4 3.38875643 1.4 2 2.69163229 8.84279E-06 0.0001904 BC056474 15 12.1 Mus musculus cDNA clone 1424117_at H3030A06 3.95752801 2.42838452 1.9 2.2 2.62132809 1.3344E-08 5.66E-07 MGC:67360 IMAGE:6823629, complete cds NA 4 153 guanine nucleotide binding protein, 1454696_at -3.46081884 -4 -1.3 -1.6 -2.6026947 8.58458E-05 0.0012617 beta 1 Gnb1 4 153 guanine nucleotide binding protein, 1417432_a_at H3094D02 -3.13334396 -4 -1.6 -1.7 -2.5946297 1.04542E-05 0.0002202 beta 1 Gadd45gip1 8 84.1 RAD23a homolog (S. -

Genetic Background Effects of Keratin 8 and 18 in a DDC-Induced Hepatotoxicity and Mallory-Denk Body Formation Mouse Model

Laboratory Investigation (2012) 92, 857–867 & 2012 USCAP, Inc All rights reserved 0023-6837/12 $32.00 Genetic background effects of keratin 8 and 18 in a DDC-induced hepatotoxicity and Mallory-Denk body formation mouse model Johannes Haybaeck1, Cornelia Stumptner1, Andrea Thueringer1, Thomas Kolbe2, Thomas M Magin3, Michael Hesse4, Peter Fickert5, Oleksiy Tsybrovskyy1, Heimo Mu¨ller1, Michael Trauner5,6, Kurt Zatloukal1 and Helmut Denk1 Keratin 8 (K8) and keratin 18 (K18) form the major hepatocyte cytoskeleton. We investigated the impact of genetic loss of either K8 or K18 on liver homeostasis under toxic stress with the hypothesis that K8 and K18 exert different functions. krt8À/À and krt18À/À mice crossed into the same 129-ola genetic background were treated by acute and chronic ad- ministration of 3,5-diethoxy-carbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine (DDC). In acutely DDC-intoxicated mice, macrovesicular steatosis was more pronounced in krt8À/À and krt18À/À compared with wild-type (wt) animals. Mallory-Denk bodies (MDBs) appeared in krt18À/À mice already at an early stage of intoxication in contrast to krt8À/À mice that did not display MDB formation when fed with DDC. Keratin-deficient mice displayed significantly lower numbers of apoptotic hepatocytes than wt animals. krt8À/À, krt18À/À and control mice displayed comparable cell proliferation rates. Chronically DDC-intoxicated krt18À/À and wt mice showed a similarly increased degree of steatohepatitis with hepatocyte ballooning and MDB formation. In krt8À/À mice, steatosis was less, ballooning, and MDBs were absent. krt18À/À mice developed MDBs whereas krt8À/À mice on the same genetic background did not, highlighting the significance of different structural properties of keratins. -

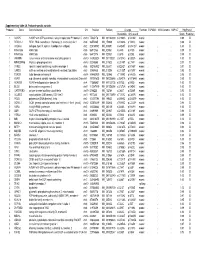

List of Genes Associated with Sudden Cardiac Death (Scdgseta) Gene

List of genes associated with sudden cardiac death (SCDgseta) mRNA expression in normal human heart Entrez_I Gene symbol Gene name Uniprot ID Uniprot name fromb D GTEx BioGPS SAGE c d e ATP-binding cassette subfamily B ABCB1 P08183 MDR1_HUMAN 5243 √ √ member 1 ATP-binding cassette subfamily C ABCC9 O60706 ABCC9_HUMAN 10060 √ √ member 9 ACE Angiotensin I–converting enzyme P12821 ACE_HUMAN 1636 √ √ ACE2 Angiotensin I–converting enzyme 2 Q9BYF1 ACE2_HUMAN 59272 √ √ Acetylcholinesterase (Cartwright ACHE P22303 ACES_HUMAN 43 √ √ blood group) ACTC1 Actin, alpha, cardiac muscle 1 P68032 ACTC_HUMAN 70 √ √ ACTN2 Actinin alpha 2 P35609 ACTN2_HUMAN 88 √ √ √ ACTN4 Actinin alpha 4 O43707 ACTN4_HUMAN 81 √ √ √ ADRA2B Adrenoceptor alpha 2B P18089 ADA2B_HUMAN 151 √ √ AGT Angiotensinogen P01019 ANGT_HUMAN 183 √ √ √ AGTR1 Angiotensin II receptor type 1 P30556 AGTR1_HUMAN 185 √ √ AGTR2 Angiotensin II receptor type 2 P50052 AGTR2_HUMAN 186 √ √ AKAP9 A-kinase anchoring protein 9 Q99996 AKAP9_HUMAN 10142 √ √ √ ANK2/ANKB/ANKYRI Ankyrin 2 Q01484 ANK2_HUMAN 287 √ √ √ N B ANKRD1 Ankyrin repeat domain 1 Q15327 ANKR1_HUMAN 27063 √ √ √ ANKRD9 Ankyrin repeat domain 9 Q96BM1 ANKR9_HUMAN 122416 √ √ ARHGAP24 Rho GTPase–activating protein 24 Q8N264 RHG24_HUMAN 83478 √ √ ATPase Na+/K+–transporting ATP1B1 P05026 AT1B1_HUMAN 481 √ √ √ subunit beta 1 ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic ATP2A2 P16615 AT2A2_HUMAN 488 √ √ √ reticulum Ca2+ transporting 2 AZIN1 Antizyme inhibitor 1 O14977 AZIN1_HUMAN 51582 √ √ √ UDP-GlcNAc: betaGal B3GNT7 beta-1,3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransfe Q8NFL0 -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Identification of KIF4A and Its Effect on the Progression of Lung

Bioscience Reports (2021) 41 BSR20203973 https://doi.org/10.1042/BSR20203973 Research Article Identification of KIF4A and its effect on the progression of lung adenocarcinoma based on the bioinformatics analysis Yexun Song1, Wenfang Tang2 and Hui Li2 Downloaded from http://portlandpress.com/bioscirep/article-pdf/41/1/BSR20203973/902647/bsr-2020-3973.pdf by guest on 03 October 2021 1Department of Otolaryngology-Head Neck Surgery, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410008, Hunan Province, China; 2Department of Respiratory Medicine, The First Hospital of Changsha, Changsha 410000, Hunan Province, China Correspondence: HuiLi([email protected]) Background: Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) is the most frequent histological type of lung cancer, and its incidence has displayed an upward trend in recent years. Nevertheless, little is known regarding effective biomarkers for LUAD. Methods: The robust rank aggregation method was used to mine differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from the gene expression omnibus (GEO) datasets. The Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING) database was used to extract hub genes from the protein–protein interaction (PPI) network. The expression of the hub genes was validated us- ing expression profiles from TCGA and Oncomine databases and was verified by real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR). The module and survival analyses of the hub genes were de- termined using Cytoscape and Kaplan–Meier curves. The function of KIF4A as a hub gene was investigated in LUAD cell lines. Results: The PPI analysis identified seven DEGs including BIRC5, DLGAP5, CENPF, KIF4A, TOP2A, AURKA, and CCNA2, which were significantly upregulated in Oncomine and TCGA LUAD datasets, and were verified by qRT-PCR in our clinical samples. -

Functional Parsing of Driver Mutations in the Colorectal Cancer Genome Reveals Numerous Suppressors of Anchorage-Independent

Supplementary information Functional parsing of driver mutations in the colorectal cancer genome reveals numerous suppressors of anchorage-independent growth Ugur Eskiocak1, Sang Bum Kim1, Peter Ly1, Andres I. Roig1, Sebastian Biglione1, Kakajan Komurov2, Crystal Cornelius1, Woodring E. Wright1, Michael A. White1, and Jerry W. Shay1. 1Department of Cell Biology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Boulevard, Dallas, TX 75390-9039. 2Department of Systems Biology, University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77054. Supplementary Figure S1. K-rasV12 expressing cells are resistant to p53 induced apoptosis. Whole-cell extracts from immortalized K-rasV12 or p53 down regulated HCECs were immunoblotted with p53 and its down-stream effectors after 10 Gy gamma-radiation. ! Supplementary Figure S2. Quantitative validation of selected shRNAs for their ability to enhance soft-agar growth of immortalized shTP53 expressing HCECs. Each bar represents 8 data points (quadruplicates from two separate experiments). Arrows denote shRNAs that failed to enhance anchorage-independent growth in a statistically significant manner. Enhancement for all other shRNAs were significant (two tailed Studentʼs t-test, compared to none, mean ± s.e.m., P<0.05)." ! Supplementary Figure S3. Ability of shRNAs to knockdown expression was demonstrated by A, immunoblotting for K-ras or B-E, Quantitative RT-PCR for ERICH1, PTPRU, SLC22A15 and SLC44A4 48 hours after transfection into 293FT cells. Two out of 23 tested shRNAs did not provide any knockdown. " ! Supplementary Figure S4. shRNAs against A, PTEN and B, NF1 do not enhance soft agar growth in HCECs without oncogenic manipulations (Student!s t-test, compared to none, mean ± s.e.m., ns= non-significant). -

Molecular Pathways Associated with the Nutritional Programming of Plant-Based Diet Acceptance in Rainbow Trout Following an Early Feeding Exposure Mukundh N

Molecular pathways associated with the nutritional programming of plant-based diet acceptance in rainbow trout following an early feeding exposure Mukundh N. Balasubramanian, Stéphane Panserat, Mathilde Dupont-Nivet, Edwige Quillet, Jérôme Montfort, Aurélie Le Cam, Françoise Médale, Sadasivam J. Kaushik, Inge Geurden To cite this version: Mukundh N. Balasubramanian, Stéphane Panserat, Mathilde Dupont-Nivet, Edwige Quillet, Jérôme Montfort, et al.. Molecular pathways associated with the nutritional programming of plant-based diet acceptance in rainbow trout following an early feeding exposure. BMC Genomics, BioMed Central, 2016, 17 (1), pp.1-20. 10.1186/s12864-016-2804-1. hal-01346912 HAL Id: hal-01346912 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01346912 Submitted on 19 Jul 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Balasubramanian et al. BMC Genomics (2016) 17:449 DOI 10.1186/s12864-016-2804-1 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Molecular pathways associated with the nutritional programming of plant-based diet acceptance in rainbow trout following an early feeding exposure Mukundh N. Balasubramanian1, Stephane Panserat1, Mathilde Dupont-Nivet2, Edwige Quillet2, Jerome Montfort3, Aurelie Le Cam3, Francoise Medale1, Sadasivam J. Kaushik1 and Inge Geurden1* Abstract Background: The achievement of sustainable feeding practices in aquaculture by reducing the reliance on wild-captured fish, via replacement of fish-based feed with plant-based feed, is impeded by the poor growth response seen in fish fed high levels of plant ingredients. -

Supplementary Table 2A. Proband-Specific Variants Proband

Supplementary table 2A. Proband-specific variants Proband Gene Gene full name Chr Position RefSeqChange Function ESP6500 1000 Genome SNP137 PolyPhen2 Nucleotide Amino acid Score Prediction 1 AGAP5 ArfGAP with GTPase domain, ankyrin repeat and PH domain 5 chr10 75435178 NM_001144000 c.G1240A p.V414M exonic . 0.99 D 1 REXO1L1 REX1, RNA exonuclease 1 homolog (S. cerevisiae)-like 1 chr8 86574465 NM_172239 c.A1262G p.Y421C exonic . 0.98 D 1 COL4A3 collagen, type IV, alpha 3 (Goodpasture antigen) chr2 228169782 NM_000091 c.G4235T p.G1412V exonic . 1.00 D 1 KIAA1586 KIAA1586 chr6 56912133 NM_020931 c.C44G p.A15G exonic . 0.99 D 1 KIAA1586 KIAA1586 chr6 56912176 NM_020931 c.C87G p.D29E exonic . 0.99 D 1 JAKMIP3 Janus kinase and microtubule interacting protein 3 chr10 133955524 NM_001105521 c.G1574C p.G525A exonic . 1.00 D 1 MPHOSPH8 M-phase phosphoprotein 8 chr13 20240685 NM_017520 c.C2140T p.L714F exonic . 0.97 D 1 SYNE1 spectrin repeat containing, nuclear envelope 1 chr6 152783902 NM_033071 c.A2242T p.N748Y exonic . 0.97 D 1 CAND2 cullin-associated and neddylation-dissociated 2 (putative) chr3 12858835 NM_012298 c.C2125T p.H709Y exonic . 0.95 D 1 TDRD9 tudor domain containing 9 chr14 104460909 NM_153046 c.T1289G p.V430G exonic . 0.96 D 2 ASPM asp (abnormal spindle) homolog, microcephaly associated (Drosophila)chr1 197091625 NM_001206846 c.G3491A p.R1164H exonic . 0.99 D 2 ADAM29 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 29 chr4 175896951 NM_001130705 c.A275G p.D92G exonic . 1.00 D 2 BCO2 beta-carotene oxygenase 2 chr11 112087019 NM_001256398 c.G1373A p.G458E exonic . -

Hypomesus Transpacificus

Aquatic Toxicology 105 (2011) 369–377 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Aquatic Toxicology jou rnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/aquatox Sublethal responses to ammonia exposure in the endangered delta smelt; Hypomesus transpacificus (Fam. Osmeridae) ∗ 1 2 Richard E. Connon , Linda A. Deanovic, Erika B. Fritsch, Leandro S. D’Abronzo , Inge Werner Aquatic Toxicology Laboratory, Department of Anatomy, Physiology and Cell Biology, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, California 95616, United States a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: The delta smelt (Hypomesus transpacificus) is an endangered pelagic fish species endemic to the Received 9 May 2011 Sacramento-San Joaquin Estuary in Northern California, which acts as an indicator of ecosystem health Received in revised form 29 June 2011 in its habitat range. Interrogative tools are required to successfully monitor effects of contaminants upon Accepted 2 July 2011 the delta smelt, and to research potential causes of population decline in this species. We used microarray technology to investigate genome-wide effects in fish exposed to ammonia; one of multiple contami- Keywords: nants arising from wastewater treatment plants and agricultural runoff. A 4-day exposure of 57-day Hypomesus transpacificus + old juveniles resulted in a total ammonium (NH4 –N) median lethal concentration (LC50) of 13 mg/L, Delta smelt Microarray and a corresponding un-ionized ammonia (NH3) LC50 of 147 g/L. Using the previously designed delta + Biomarker smelt microarray we assessed altered gene transcription in juveniles exposed to 10 mg/L NH4 –N from Ammonia this 4-day exposure. -

Wnt/Β-Catenin Signaling Induces MLL to Create Epigenetic Changes In

Wend et al. page 1 Wnt/ȕ-catenin signaling induces MLL to create epigenetic changes in salivary gland tumors Peter Wend1,7, Liang Fang1, Qionghua Zhu1, Jörg H. Schipper2, Christoph Loddenkemper3, Frauke Kosel1, Volker Brinkmann4, Klaus Eckert1, Simone Hindersin2, Jane D. Holland1, Stephan Lehr5, Michael Kahn6, Ulrike Ziebold1,*, Walter Birchmeier1,* 1Max-Delbrueck Center for Molecular Medicine, Robert-Rössle-Str. 10, 13125 Berlin, Germany 2Department of Otorhinolaryngology, University Hospital Düsseldorf, Moorenstr. 5, 40225 Düsseldorf, Germany 3Institute of Pathology, Charité-UKBF, Hindenburgdamm 30, 12200 Berlin, Germany 4Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology, Schumannstr. 20, 10117 Berlin, Germany 5Baxter Innovations GmbH, Wagramer Str. 17-19, 1220 Vienna, Austria 6Eli and Edythe Broad Center for Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90033, USA 7Present address: David Geffen School of Medicine and Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California at Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA *These senior authors contributed equally to this work. Contact: [email protected], phone: +49-30-9406-3800, fax: +49-30-9406-2656 Running title: ȕ-catenin and MLL drive salivary gland tumors Characters (including spaces): 52,604 Wend et al. page 2 Abstract We show that activation of Wnt/ȕ-catenin and attenuation of Bmp signals, by combined gain- and loss-of-function mutations of ȕ-catenin and Bmpr1a, respectively, results in rapidly growing, aggressive squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) in the salivary glands of mice. Tumors contain transplantable and hyper-proliferative tumor propagating cells, which can be enriched by FACS. Single mutations stimulate stem cells, but tumors are not formed. We show that ȕ-catenin, CBP and Mll promote self- renewal and H3K4 tri-methylation in tumor propagating cells.