Reflection on the Traits and Images Associated with Jews in 17Th Century Ottoman Sources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

235On the Trail of Evliya Çelebi's Inscriptions and Graffiti

235«A mari usque ad mare» Cultura visuale e materiale dall’Adriatico all’India a cura di Mattia Guidetti e Sara Mondini 235On the Trail of Evliya Çelebi’s Inscriptions and Graffiti Mehmet Tütüncü (Research Centre for Turkish and Arabic World, Haarlem, Netherlands) Abstract The Turkish traveller Evliya Çelebi was accustomed to leave a small graffito, or even a skillfully carved inscription, in the places he visited during his long travels across the whole Otto- man World. These traces can be compared with what he recorded in his oceanic Seyahatname and in other writings, a work in progress whose first results are offered in this paper. Summary 1 Introduction. – 2 Inscriptions Written by Evliya Çelebi. – 2.1 The Uyvar (Nové Zámky) Inscriptions. – 2.2 Crete-Kandiye (Heraklion). – 2.3 Zarnata Castle. – 2.4 Mora Zarnata Mosque. – 3 Evliya Çelebi’s Memento Inscriptions (graffiti). – 3.1 Wall and Tree Inscriptions Mentioned in the Seyahatname. – 3.2 Not Mentioned Wall Inscriptions in the Seyahatname. – 3.3 Evliya Çelebi’s Inscription on Pir Ahmed Efendi Mosque. – 3.4 Evliya’s graffito in Pécs (Hungary). Keywords Evliya Çelebi. Ottoman inscriptions. Balkans. I first met Gianclaudio in 2009 in a Symposium about Bektashism in Albania in Tirana (fig. 1). He presented there his findings of the Survey in Delvina, with a focus on the graffiti in the portico of Gjin Aleksi Mosque. On that oc- casion we spoke about the findings and I speculated that this graffiti could be the work of Evliya Çelebi and asked whether I could join him to see and inspect the graffiti. -

Doktora Tezi Evliyâ Çelebi'nin Acayip Ve Garip Dünyasi Yeliz Özay Türk Edebiyati Bölümü Ihsan Doğramaci

DOKTORA TEZİ EVLİYÂ ÇELEBİ’NİN ACAYİP VE GARİP DÜNYASI YELİZ ÖZAY TÜRK EDEBİYATI BÖLÜMÜ İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT ÜNİVERSİTESİ, ANKARA EYLÜL 2012 İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent Üniversitesi Ekonomi ve Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü EVLİYÂ ÇELEBİ’NİN ACAYİP VE GARİP DÜNYASI YELİZ ÖZAY Türk Edebiyatı Bölümünde Doktora Derecesi Kazanma Yükümlülüklerinin Bir Parçasıdır. Türk Edebiyatı Bölümü İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent Üniversitesi, Ankara Eylül 2012 Bütün hakları saklıdır. Kaynak göstermek koşuluyla alıntı ve gönderme yapılabilir. © Yeliz Özay, 2012 Bu tezi okuduğumu, kapsam ve nitelik bakımından Türk Edebiyatında Doktora derecesi için yeterli bulduğumu beyan ederim. ………………………………………… Yrd. Doç. Dr. Nuran Tezcan Tez Danışmanı Bu tezi okuduğumu, kapsam ve nitelik bakımından Türk Edebiyatında Doktora derecesi için yeterli bulduğumu beyan ederim. ………………………………………… Prof. Talât Halman Tez Jürisi Üyesi Bu tezi okuduğumu, kapsam ve nitelik bakımından Türk Edebiyatında Doktora derecesi için yeterli bulduğumu beyan ederim. ………………………………………… Prof. Dr. Semih Tezcan Tez Jürisi Üyesi Bu tezi okuduğumu, kapsam ve nitelik bakımından Türk Edebiyatında Doktora derecesi için yeterli bulduğumu beyan ederim. ………………………………………… Prof. Dr. Öcal Oğuz Tez Jürisi Üyesi Bu tezi okuduğumu, kapsam ve nitelik bakımından Türk Edebiyatında Doktora derecesi için yeterli bulduğumu beyan ederim. ………………………………………… Yrd. Doç. Dr. Oktay Özel Tez Jürisi Üyesi Ekonomi ve Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Müdürü’nün onayı ………………………………………… Prof. Dr. Erdal Erel Enstitü Müdürü ÖZET EVLİYÂ ÇELEBİ’NİN ACAYİP VE GARİP DÜNYASI Özay Yeliz Doktora, Türk Edebiyatı Tez Yöneticisi: Doç. Dr. Nuran Tezcan Eylül, 2012 Evliyâ Çelebi, Seyahatnâme’de yineleyerek vurguladığı kimi başlıklarla okurun dikkatini özellikle bazı anlatı kategorilerine çekmektedir. Bu kategorilerden biri de yapıtın kurmaca boyutunun ve Evliyâ’nın “hikâye anlatıcı”lığının tartışılabilmesi için son derece önemli olan acayib ü garayibyani “acayiplikler ve gariplikler”dir.Bu çalışmada, “Evliyâ Çelebi’nin Acayip ve Garip Dünyası”, 17. -

Contextualizing an 18 Century Ottoman Elite: Şerđf Halđl Paşa of Şumnu and His Patronage

CONTEXTUALIZING AN 18TH CENTURY OTTOMAN ELITE: ŞERĐF HALĐL PAŞA OF ŞUMNU AND HIS PATRONAGE by AHMET BĐLALOĞLU Submitted to the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Sabancı University 2011 CONTEXTUALIZING AN 18TH CENTURY OTTOMAN ELITE: ŞERĐF HALĐL PAŞA OF ŞUMNU AND HIS PATRONAGE APPROVED BY: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Tülay Artan …………………………. (Dissertation Supervisor) Assist. Prof. Dr. Hülya Adak …………………………. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Bratislav Pantelic …………………………. DATE OF APPROVAL: 8 SEPTEMBER 2011 © Ahmet Bilaloğlu, 2011 All rights Reserved ABSTRACT CONTEXTUALIZING AN 18 TH CENTURY OTTOMAN ELITE: ŞERĐF HALĐL PAŞA OF ŞUMNU AND HIS PATRONAGE Ahmet Bilaloğlu History, MA Thesis, 2011 Thesis Supervisor: Tülay Artan Keywords: Şumnu, Şerif Halil Paşa, Tombul Mosque, Şumnu library. The fundamental aim of this thesis is to present the career of Şerif Halil Paşa of Şumnu who has only been mentioned in scholarly research due to the socio-religious complex that he commissioned in his hometown. Furthermore, it is aimed to portray Şerif Halil within a larger circle of elites and their common interests in the first half of the 18 th century. For the study, various chronicles, archival records and biographical dictionaries have been used as primary sources. The vakıfnâme of the socio-religious complex of Şerif Halil proved to be a rare example which included some valuable biographical facts about the patron. Apart from the official posts that Şerif Halil Paşa occupied in the Defterhâne and the Divânhâne , this study attempts to render his patronage of architecture as well as his intellectual interests such as calligraphy and literature. -

Istanbul As a Military Target

Istanbul as a Military Target Christine Isom-Verhaaren Brigham Young University The Ottomans viewed Istanbul as the ideal capital of their Empire long before its conquest in 1453. However Istanbul both benefitted and suffered from its location on the straits that connect- ed the Mediterranean to the Black Sea. Mehmed II’s rebuilding of the city into a thriving metropolis brought the danger that enemies of the Ottomans would consider access to the city as a military strategy. Istanbul’s large population required an elaborate system of supply to feed the city and sea borne trade was vital for the city’s prosperity.1 This transformed the need for an effective Ottoman naval force from a desirable option to an absolute necessity. The creation and maintenance of effective naval power progressed une- venly from the 1450s with Mehmed II’s creation of a large but not particularly high quality navy. Bayezid II improved the empire’s naval forces through the recruitment of the corsair Kemal Reis as a commander. During the reign of Süleyman, under the former corsair, 1 Colin Imber, “Before the Kapudan Pashas: Sea Power and the Emergence of the Ottoman Empire,” The Kapudan Pasha: His Office and his Domain, Halycon Days in Crete IV, a symposium held in Rethymnon 7-9 January 2000, ed. Elizabeth Zachariadou (Rethymnon: University of Crete Press, 2002), 49-59. 719 OSMANLI ó STANBULU IV Admiral Hayreddin Pasha, Ottoman naval power extended to the western Mediterranean and the shores of Algiers. Hayreddin led the Ottoman navy so effectively that he defeated the combined forces of Venice and Habsburg Spain under the Genoese admiral Andrea Doria at Preveza in 1538. -

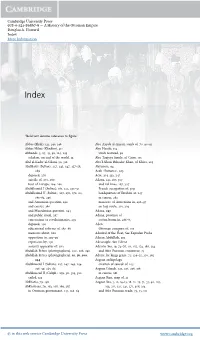

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89867-6 — a History of the Ottoman Empire Douglas A

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89867-6 — A History of the Ottoman Empire Douglas A. Howard Index More Information Index “Bold text denotes reference to figure” Abbas (Shah), 121, 140, 148 Abu Ayyub al-Ansari, tomb of, 70, 90–91 Abbas Hilmi (Khedive), 311 Abu Hanifa, 114 Abbasids, 3, 27, 45, 92, 124, 149 tomb restored, 92 scholars, on end of the world, 53 Abu Taqiyya family, of Cairo, 155 Abd al-Kader al-Gilani, 92, 316 Abu’l-Ghazi Bahadur Khan, of Khiva, 265 Abdülaziz (Sultan), 227, 245, 247, 257–58, Abyssinia, 94 289 Aceh (Sumatra), 203 deposed, 270 Acre, 214, 233, 247 suicide of, 270, 280 Adana, 141, 287, 307 tour of Europe, 264, 266 and rail lines, 287, 307 Abdülhamid I (Sultan), 181, 222, 230–31 French occupation of, 309 Abdülhamid II (Sultan), 227, 270, 278–80, headquarters of Ibrahim at, 247 283–84, 296 in census, 282 and Armenian question, 292 massacre of Armenians in, 296–97 and census, 280 on hajj route, 201, 203 and Macedonian question, 294 Adana, 297 and public ritual, 287 Adana, province of concessions to revolutionaries, 295 cotton boom in, 286–87 deposed, 296 Aden educational reforms of, 287–88 Ottoman conquest of, 105 memoirs about, 280 Admiral of the Fleet, See Kapudan Pasha opposition to, 292–93 Adnan Abdülhak, 319 repression by, 292 Adrianople. See Edirne security apparatus of, 280 Adriatic Sea, 19, 74–76, 111, 155, 174, 186, 234 Abdullah Frères (photographers), 200, 288, 290 and Afro-Eurasian commerce, 74 Abdullah Frères (photographers), 10, 56, 200, Advice for kings genre, 71, 124–25, 150, 262 244 Aegean archipelago -

The Rise of Köprülü Mehmed Pasha

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/69483 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Bekar C. Title: The rise of the Köprülü family: the reconfiguration of vizierial power in the seventeenth century Issue Date: 2019-03-06 CHAPTER 2: THE RISE OF KÖPRÜLÜ MEHMED PASHA: RESTORATION OF THE AUTHORITY OF THE GRAND VIZIER (1651-1661) 2.1. Introduction In the year 1067 (1656) the courier of the Crimean sultan Mehmed Giray Khan, whose name was Colaq Dedeş Agha, arrived from the felicitous Threshold on his way back to the Crimea, bearing letters for our lord the pasha. “Amazing”, cried the Pasha when he read the letters. “My Evliya, have you heard?” he went on in his astonishment. “Boynu Egri Mehmed Pasha has been dismissed from the grand vizierate, and Köprülü Mehmed Pasha has been appointed in his place.” “Well, my sultan,” piped up the seal keeper, Osman Agha, “just see what an evil day the Ottoman state has reached, when we get as grand vizier a miserable wretch like Köprülü, who could not even give straw to a pair of oxen!”124 The famous traveler Evliya Çelebi recorded this dialogue in his voluminous travels-cum- memoirs when he accompanied in the Crimea his master Melek Ahmed Pasha, who was at the time the governor of Özi. The passage is important because it provides precious insights into how the appointment of Köprülü Mehmed Pasha was received by contemporary Ottoman observers. The reaction of Osman Aga indicates that Köprülü Mehmed Pasha did not have a positive public image. -

EVLIYA DEPARTS for Damascus with Its Governor Silihdar Murtaza Pasha

VOLUME THREE In the Retinue of Melek Ahmed Pasha VLIYA DEPARTS for Damascus with its governor Silihdar Murtaza Pasha Ein September 1648. On the way he stops briefly at Akşehir, home of Nasred- din Hoca, the legendary subject of so much Turkish humour. His peregrinations in the Holy Land include a stay in Safed (cf. Volume 9, selection 3) where he en- counters a community of Sephardic Jews. He considers Ladino (or Judaeo-Span- ish, which he had also heard in Istanbul and was later to hear in Salonica) to be the Jewish language par excellence. While in Damascus he has encounters with the colourful Sheikh Bekkar the Naked (cf. Volume 9, selection 5). A year later Murtaza Pasha is appointed governor of Sivas, and Evliya accom- panies him there. At the end of his long description of the city, we find the satir- ical story of the girl who gave birth to an elephant, and his description of the Armenian language. Stopping at Divriği, he sees the cats that he had found auc- tioned in Ardabil (Volume 2, selection 7). With the Pasha’s dismissal from office, Evliya returns to Istanbul in July 1650. He now attaches himself to another kinsman, Melek Ahmed Pasha. For the next twelve years Evliya is in Melek Pasha’s service, and his travel itinerary fol- lows the various posts to which the Pasha is assigned as governor (beylerbey). In this volume we hear about Evliya’s travels with Melek Pasha in Thrace and the Balkans. He reports on witchcraft in a Bulgarian village; on hot springs (cf. -

The Realization of Mehmed Iv's Ghazi Title at the Campaign of Kamaniçe

THE REALIZATION OF MEHMED IV'S GHAZİ TITLE AT THE CAMPAIGN OF KAMANİÇE By ÖZGÜN DENİZ YOLDAŞLAR Submitted to the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Sabancı University July 2013 THE REALIZATION OF MEHMED IV'S GHAZİ TITLE AT THE CAMPAIGN OF KAMANİÇE APPROVED BY: Tülay Artan …………………………. (Thesis Supervisor) İ. Metin Kunt …………………………. İzak Atiyas …………………………. DATE OF APPROVAL: …………………………. © Özgün Deniz Yoldaşlar 2013 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT THE REALIZATION OF MEHMED IV'S GHAZİ TITLE AT THE CAMPAIGN OF KAMANİÇE Özgün Deniz Yoldaşlar History, M. A. Thesis, Spring 2013 Thesis Supervisor: Tülay Artan Keywords: Mehmed IV, Ghazi Sultans, Abaza Hasan Paşa, Fazıl Ahmed Paşa, Kamaniçe. In 1658 Sultan Mehmed IV was officially given the title of Ghazi with a fatwa of the Şeyhülislam; but it was not until in 1672 that this title materialized in concrete manner. This was unique, as for the first time in Ottoman history a sultan was officially - not rhetorically- receiving the Ghazi title prior to actually taking part in a campaign. In examining this unique case, the present study poses the following questions: under what circumstances was the Ghazi title first given to Mehmed IV in 1658 and why did he join the Kamaniçe campaign in 1672? To answer these questions, it advances two arguments. First, it argues that Mehmed IV’s Ghazi title was launched by the ruling elites as a legitimization tool against Abaza Hasan Paşa, the provincial governor who had revolted against the rigid rule of the Grand Vizier Köprülü Mehmed Paşa in 1658. -

Osmanli Araştirmalari the Journal of Ottoman Studies

OSMANLI ARAŞTIRMALARI THE JOURNAL OF OTTOMAN STUDIES SAYI / ISSUE 55 • 2020 OSMANLI ARAŞTIRMALARI THE JOURNAL OF OTTOMAN STUDIES İSTANBUL 29 MAYIS ÜNİVERSİTESİ OSMANLI ARAŞTIRMALARI THE JOURNAL OF OTTOMAN STUDIES Yayın Kurulu / Editorial Board Prof. Dr. İsmail E. Erünsal – Prof. Dr. Heath Lowry Prof. Dr. Feridun M. Emecen – Prof. Dr. Ali Akyıldız Prof. Dr. Bilgin Aydın – Prof. Dr. Seyfi Kenan Prof. Dr. Jane Hathaway – Doç. Dr. Baki Tezcan İstanbul 2020 Bu dergi Arts and Humanities Citation Index – AHCI (Clarivate Analytics), Scopus (Elsevier),Turkologischer Anzeiger ve Index Islamicus tarafından taranmakta olup TÜBİTAK ULAKBİM Sosyal ve Beşeri Bilimler veri tabanında yer almaktadır. Articles in this journal are indexed or abstracted in Arts and Humanities Citation Index – AHCI (Clarivate Analytics), Scopus (Elsevier), Turkologischer Anzeiger, Index Islamicus and TÜBİTAK ULAKBİM Humanities Index. Baskı / Publication TDV Yayın Matbaacılık ve Tic. İşl. Ostim OSB Mahallesi, 1256 Cadde, No: 11 Yenimahalle / Ankara Tel. 0312. 354 91 31 Sertifika No. 15402 Sipariş / Order [email protected] Osmanlı Araştırmaları yılda iki sayı yayımlanan uluslararası hakemli bir dergidir. Dergide yer alan yazıların ilmî ve fikrî sorumluluğu yazarlarına aittir. The Journal of Ottoman Studies is a peer-reviewed, biannual journal. The responsibility of statements or opinions uttered in the articles is upon their authors. Elmalıkent Mah. Elmalıkent Cad. No: 4, 34764 Ümraniye / İstanbul Tel. (216) 474 08 60 Fax (216) 474 08 75 [email protected] © İslâm Araştırmaları Merkezi (İSAM), 2020 Osmanlı Araştırmaları / The Journal of Ottoman Studies Sayı / Issue LV · yıl / year 2020 Sahibi / Published under TDV İslâm Araştırmaları Merkezi ve İstanbul 29 Mayıs Üniversitesi adına the auspices of Prof. -

Köprülü Mehmed Pascha“ Konsolidierung Des Osmanischen Reiches Durch Zwei Außergewöhnliche Siege

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Köprülü Mehmed Pascha“ Konsolidierung des Osmanischen Reiches durch zwei außergewöhnliche Siege Verfasserin Şeyma Dönmez angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2011 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 386 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Turkologie Betreuerin: ao. Univ. -Prof. Dr. Claudia Römer 2 3 „Vergesst nicht, wer ihr seid“, mit diesen Worten schickte uns mein Onkel, der ein begeisterter Geschichtslehrer war und von dem ich die ersten Osmanischen Geschichten zu hören bekam, nach Österreich. Mein Onkel hat es nicht mehr erleben können, dass ich Turkologie studiere, aber ich möchte ihm sehr dafür danken, dass er mich dazu veranlasst hat. Einen großen Dank möchte ich auch an meine Familie und Freunde ausrichten, die mich in jeder Hinsicht unterstützt und an mich geglaubt haben. Mein ganz besonderer Dank gilt aber meiner Betreuerin ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Claudia Römer, die mich durch diese schwierige Zeit mit Ihren Ratschlägen und Anekdoten begleitet hat, immer Zeit für mich hatte und für mich viel mehr als nur eine Betreuerin gewesen ist. 4 EIDESSTATTLICHE ERKLÄRUNG Ich erkläre hiermit an Eides Statt, dass ich die vorliegende Diplomarbeit selbstständig verfasst und ohne Benutzung anderer als der angegebenen Hilfsmittel angefertigt habe. Die aus fremden Quellen direkt oder indirekt übernommenen Gedanken sind als solche kenntlich gemacht. Die Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form keiner anderen Prüfungsbehörde vorgelegt und auch noch nicht veröffentlicht. Wien, Juni 2011 Şeyma Dönmez 5 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 1. EINLEITUNG 7 2. KÖPRÜLÜ MEHMED PASCHAS LEBEN 16 3. SEIN CHARAKTER 18 4. SEIN BILDUNGSSTAND 23 5. DER BERUFSWEG VON KÖPRÜLÜ MEHMED PASCHA 25 6. ERNENNUNG ZUM GROSSWESIR 30 7. -

The Dream of a 17Th Century Ottoman Intellectual

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sabanci University Research Database THE DREAM OF A 17 TH CENTURY OTTOMAN INTELLECTUAL: VEYS İ AND HIS HABNAME by A. TUNÇ ŞEN Submitted to the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Sabancı University Spring 2008 THE DREAM OF A 17 TH CENTURY OTTOMAN INTELLECTUAL: VEYS İ AND HIS HABNAME APPROVED BY: Asst. Prof. Y. Hakan Erdem …………………………. (Thesis Supervisor) Asst. Prof. Hülya Canbakal …………………………. Asst. Prof. Hülya Adak …………………………. DATE OF APPROVAL: 06 / 08 / 2008 © A. Tunç Şen, 2008 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT THE DREAM OF A 17 TH CENTURY OTTOMAN INTELLECTUAL: VEYS İ AND HIS HABNAME A.Tunç Şen History, M.A. thesis, Spring 2008 Thesis Supervisor: Y. Hakan Erdem This thesis endeavors to present a literary-historical analysis of a seventeenth century work of prose, Habnâme , which was written by one of the prominent literary figures of his time, Veysî. He was born in Ala şehir in 1561/2, and died in 1628 in Skopje. Having been enrolled in medrese education, he worked as a kadı in various locations in both Anatolia and Rumeli including Ala şehir, Tire, Serez and Skopje. He is, however, better known for his literary abilities, and respected by both contemporary biographers and modern scholars as one of the leading figures of Ottoman ornamental prose. In his Habnâme, Veysî constructs a dream setting, in which the Alexander the Two- Horned has a conversation with Ahmed I regarding Ahmed’s concerns of the abuses in state apparatus. -

The Trip from Bursa to Edi̇rne to Join Him, He Agreed to Leave Him with the Grand Vizier

THE TRIP FROM BURSA TO EDİRNE In a peripatetic life that included forty years of sustained travel, Evliya Çelebi spent twelve years in the service of Melek Ahmed Pasha, governor of a number of Ottoman provinces and grand vizier between 1650–1651. Evliya traveled with his patron—a relative on his mother’s side—to postings in Ochakiv (Özü), Silistre, Van, Bitlis, and Sofia, remaining with him until the pasha’s death in 1662. Due to the circumstances described below, however, Evliya was away from his patron during the 1659 trip from Bursa to Edirne, traveling in the retinue of grand vizier Köprülü Mehmed Pasha. Evliya was deeply attached to his kinsman Melek Ahmed, and to his wife Qaya Sultan, a daughter of Sultan Murad IV (r. 1623–1640), who died in early 1659, a few months before Evliya’s journey. Twenty days after Melek Ahmed Pasha’s wife Qaya Sultan died, he was summoned before the young Sultan Mehmed IV along with the grand vizier Köprülü Mehmed Pasha. The sultan granted Melek Ahmed the governorship of Bosnia province and additional monetary allowances in what seems to have been an act of consolation; Evliya describes Köprülü’s astonishment at the sultan’s generosity toward Melek Ahmed. After leaving the sultan’s audi- ence, the two men quarreled over Köprülü’s recommendation that Melek Ahmed appoint one of Köprülü’s own protégés as an administrator in his newly acquired post. When Melek Ahmed Pasha set out toward Bosnia from Istanbul on 15 March 1659, Evliya was in his retinue. The pasha’s cortege quartered for a week on the Topcılar Plain to the northwest of the city as they acquired the necessary provisions for the journey.