Crisis in Mali: Ambivalent Popular Attitudes on the Way Forward Massa Coulibaly* and Michael Bratton†

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mali: Éviter L'escalade

MALI : EVITER L’ESCALADE Rapport Afrique N°189 – 18 juillet 2012 TABLE DES MATIERES SYNTHESE ET RECOMMANDATIONS ............................................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. LES DETOURS OPAQUES DE LA POLITIQUE NORDISTE D’ATT ..................... 2 A. REBELLIONS TOUAREG, PACTE NATIONAL ET ACCORDS D’ALGER ................................................ 2 B. IMPLANTATION DURABLE D’AQMI AU NORD-MALI ................................................................... 5 C. LE DERNIER AVATAR DE LA POLITIQUE SECURITAIRE D’ATT : LE PROGRAMME SPECIAL POUR LA PAIX, LA SECURITE ET LE DEVELOPPEMENT AU NORD-MALI ....................................................... 6 D. DU MNA AU MNLA : LA GESTATION D’UNE REBELLION ............................................................. 7 III. MAINTENANT OU JAMAIS ? LA RESURGENCE DE LA REBELLION ............. 9 A. LE FACTEUR LIBYEN : KADHAFI ET LE NORD-MALI ..................................................................... 9 B. LA MONTEE EN PUISSANCE DU MNLA ....................................................................................... 11 C. IYAD AG GHALI, SES AMBITIONS PERSONNELLES CONTRARIEES ET L’AGENDA ISLAMISTE .......... 12 IV. UNE DYNAMIQUE REBELLE ECLATEE ET VOLATILE.................................... 14 A. LA CAMPAGNE MILITAIRE FULGURANTE DES GROUPES ARMES DU NORD .................................... 14 B. LES EVENEMENTS D’AGUELHOC ET LES -

Adhésion 2019

Adhésion 2019 Archipel des Sciences vous invite à adhérer pour l’année 2019. La cotisation est de 30 €, 10 € pour les étudiants et 100 € pour les personnes morales. Vous avez désormais la possibilité d' adhérer en ligne sur le site d' Archipel des Sciences . Vous pouvez également télécharger le formulaire d’adhésion ici . Archipel des Sciences vous remercie de l’intérêt que vous porter à la culture scientifique, technique et industrielle. Demandez le catalogue ! Archipel des Sciences vous présente son catalogue d'outils pédagogiques et ses possibilités d'animations à destination du public scolaire. Depuis de nombreuses années, le Centre de Culture Scientifique, Technique et Industrielle (CCSTI) de Guadeloupe n'a cessé d'œuvrer dans le domaine de la culture scientifique. Les diverses thématiques qui sous- Le scientifique du mois Cheick Modibo Diarra Modibo Diarra est le fils d'un commis de l’administration coloniale ; ce dernier a quatre femmes et trois enfants. Après l'indépendance du Mali, il est déporté pour des motifs politiques. Le jeune Modibo grandit donc sans son père, où il alterne ses études à l'école et les travaux des champs. Il exerce plusieurs « petits métiers », comme vendeur de colliers dans la rue ou encore gérant de boîte de nuit. Après avoir obtenu son baccalauréat au Mali au lycée technique de Bamako, Modibo Diarra étudie les mathématiques, la physique et la mécanique analytique à Paris à l’université Pierre-et-Marie-Curie (grâce à une bourse), à l'École centrale, puis l’ingénierie aérospatiale aux États-Unis à l'université Howard (Washington D.C.). Débarqué en 1979, c'est par hasard qu'il intègre cette dernière université : plus jeune, Modibo s'était juré de ne jamais mettre les pieds dans l'Amérique de la ségrégation raciale. -

The Force of Action: Legitimizing the Coup in Bamako, Mali Bruce Whitehouse

● ● ● ● Africa Spectrum 2-3/2012: 93-110 The Force of Action: Legitimizing the Coup in Bamako, Mali Bruce Whitehouse Abstract: The coup d’état that occurred in Bamako in March 2012 brought a previously unknown army captain named Amadou Sanogo to power. This paper analyses Malian media reports to explore how Sanogo and his associ- ates sought to legitimize their takeover with reference to local conceptions of heroism, power and destiny, and how Sanogo’s public image resonated with time-honoured narratives about heroic figures in Malian culture. This case demonstrates that understanding religious worldviews is essential for understanding the workings of political power. Manuscript received 2 October 2012; accepted 7 October 2012 Keywords: Mali, coup d’état/military insurrection, political culture Bruce Whitehouse is an assistant professor of Anthropology at Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, where he also teaches courses in global studies and Africana studies. From August 2011 until May 2012 he was a Fulbright Scholar in Bamako, Mali, where he lectured at the Université des Lettres et des Sciences Humaines de Bamako. 94 Bruce Whitehouse When a coup d’état toppled Mali’s President Amadou Toumani Touré two months before the end of his second and final term of office, the man who led the putsch became the object of intense scrutiny by Malians and outside observers alike. This young army officer achieved overnight celebrity status in Bamako in the early morning of 22 March, when in his initial appearance on Mali’s ORTM state television, wearing camouflage fatigues and a cap pulled low over his forehead, he hoarsely read a terse appeal for calm. -

Ibrahim Boubacar Keita

Ibrahim Boubacar Keita Malí, Presidente de la República Duración del mandato: 04 de Septiembre de 2013 - En funciones Nacimiento: Koutiala, región de Sikasso, 29 de Enero de 1945 Partido político: RPM Profesión : Politólogo y consultor ResumenLas elecciones celebradas en Malí en julio y agosto de 2013, tras año y medio de gravísima crisis nacional, sentaron en la Presidencia de la República a Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, veterano dirigente político que ya había intentado ganar el mandato en las votaciones de 2002 y 2007. El respetado Keita, un experto en cuestiones del desarrollo y con buenas conexiones en el exterior, se distinguió en la oposición a la dictadura de Moussa Traoré (1968-1991) y luego fue uno de los pilares de la democracia malí, a la que sirvió como cofundador del partido ADEMA, primer ministro (1994-2000) con el presidente Alpha Oumar Konaré y jefe de la Asamblea Nacional (2002-2007) con Amadou Toumani Touré. Desde 2001 lidera una formación, el RPM, orientada al centro-izquierda.A los ojos de la comunidad internacional y de la gran mayoría de sus paisanos, Keita, llamado habitualmente IBK, con su reputación de hombre firme y a la vez pragmático, es la única figura capaz de asegurar la integridad de este empobrecido Estado del área sahelo-sahariana, que en enero de 2012 vio saltar por los aires dos décadas de estabilidad considerada modélica.La revuelta tuareg -la cuarta o quinta desde la independencia en 1960- en las vastas regiones desérticas del norte, el inicuo golpe del capitán Sanogo, que derrocó al presidente Touré, la proclamación por los rebeldes separatistas del Estado Independiente de Azawad y el auge espectacular de la subversión jihadista al socaire de todo lo anterior dibujaron un aciago escenario de guerra civil, usurpación castrense y partición territorial de facto que la intervención internacional por etapas, civil y militar, de los gobiernos de la región, de Francia y de la ONU pudo revertir en buena medida, aunque no del todo. -

2016 Country Review

Mali 2016 Country Review http://www.countrywatch.com Table of Contents Chapter 1 1 Country Overview 1 Country Overview 2 Key Data 5 Mali 6 Africa 7 Chapter 2 9 Political Overview 9 History 10 Political Conditions 12 Political Risk Index 66 Political Stability 81 Freedom Rankings 96 Human Rights 108 Government Functions 110 Government Structure 111 Principal Government Officials 121 Leader Biography 122 Leader Biography 122 Foreign Relations 131 National Security 143 Defense Forces 154 Chapter 3 156 Economic Overview 156 Economic Overview 157 Nominal GDP and Components 159 Population and GDP Per Capita 160 Real GDP and Inflation 161 Government Spending and Taxation 162 Money Supply, Interest Rates and Unemployment 163 Foreign Trade and the Exchange Rate 164 Data in US Dollars 165 Energy Consumption and Production Standard Units 166 Energy Consumption and Production QUADS 167 World Energy Price Summary 168 CO2 Emissions 169 Agriculture Consumption and Production 170 World Agriculture Pricing Summary 172 Metals Consumption and Production 173 World Metals Pricing Summary 175 Economic Performance Index 176 Chapter 4 188 Investment Overview 188 Foreign Investment Climate 189 Foreign Investment Index 193 Corruption Perceptions Index 206 Competitiveness Ranking 217 Taxation 226 Stock Market 227 Partner Links 227 Chapter 5 229 Social Overview 229 People 230 Human Development Index 232 Life Satisfaction Index 236 Happy Planet Index 247 Status of Women 256 Global Gender Gap Index 259 Culture and Arts 268 Etiquette 268 Travel Information 269 Diseases/Health Data 280 Chapter 6 287 Environmental Overview 287 Environmental Issues 288 Environmental Policy 288 Greenhouse Gas Ranking 290 Global Environmental Snapshot 301 Global Environmental Concepts 312 International Environmental Agreements and Associations 326 Appendices 350 Bibliography 351 Mali Chapter 1 Country Overview Mali Review 2016 Page 1 of 363 pages Mali Country Overview MALI Located in western Africa, the landlocked Mali is one of the poorest countries in the world. -

The Executive Survey General Information and Guidelines

The Executive Survey General Information and Guidelines Dear Country Expert, In this section, we distinguish between the head of state (HOS) and the head of government (HOG). • The Head of State (HOS) is an individual or collective body that serves as the chief public representative of the country; his or her function could be purely ceremonial. • The Head of Government (HOG) is the chief officer(s) of the executive branch of government; the HOG may also be HOS, in which case the executive survey only pertains to the HOS. • The executive survey applies to the person who effectively holds these positions in practice. • The HOS/HOG pair will always include the effective ruler of the country, even if for a period this is the commander of foreign occupying forces. • The HOS and/or HOG must rule over a significant part of the country’s territory. • The HOS and/or HOG must be a resident of the country — governments in exile are not listed. • By implication, if you are considering a semi-sovereign territory, such as a colony or an annexed territory, the HOS and/or HOG will be a person located in the territory in question, not in the capital of the colonizing/annexing country. • Only HOSs and/or HOGs who stay in power for 100 consecutive days or more will be included in the surveys. • A country may go without a HOG but there will be no period listed with only a HOG and no HOS. • If a HOG also becomes HOS (interim or full), s/he is moved to the HOS list and removed from the HOG list for the duration of their tenure. -

Freedom to Innovate

Freedom to Innovate Biotechnology in Africa’s Development Report of the High-Level African Panel on Modern Biotechnology Freedom to Innovate Biotechnology in Africa’s Development Report of the High-Level African Panel on Modern Biotechnology Calestous Juma Ismail Serageldin Co-Chairs Amadou Tidiane • Ba Mpoko Bokanga • Abdallah Daar • Cheikh Modibo Diarra • Tewolde Egziabher • Lydia Makhubu • Dawn Mokhobo • Lewis Mughogho • Samuel Nzietchueng • George Sarpong • Cyrie Sendashonga • Ahmed Shembesh Panel Members African Union • Union Africaine New Partnership for Africa's Development August 2007 www.africa-union.org • www.nepadst.org © 2007, African Union (AU) and New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) NON-COMMERCIAL REPRODUCTION Information in this publication may be reproduced in part or in whole. We ask only that: • Users notify the NEPAD secretariat. • Users exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced. • The African Union (AU) and the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) be identified as the source. • The reproduction is not represented as an official version of the materials reproduced, nor as having been made in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the AU and NEPAD. COMMERCIAL REPRODUCTION Reproduction of multiple copies of materials in this publication, in whole or in part, for the purposes of commercial redistribution is prohibited except with written permission from the AU and NEPAD. To obtain permission to reproduce materials from this publication for commercial purposes, please contact the NEPAD secretariat at: [email protected]. SUGGESTED CITATION: “Juma, C. and Serageldin, I. (Lead Authors) (2007). ‘Freedom to Innovate: Biotechnology in Africa’s Development’, A report of the High-Level African Panel on Modern Biotechnology. -

What If the Sun Also Rises in the West… the New Global Dynamics 6, 7 and 8 July 2012 List of Confirmed Speakers – 3 July 2012

What if the Sun also Rises in the West… The New Global Dynamics 6, 7 and 8 July 2012 List of Confirmed Speakers – 3 July 2012 POSITIVE ANSWERS Ronny ABRAHAM – Judge, International Court of Justice Philippe AGHION – Professor, Harvard University Michel AGLIETTA – Scientific Advisor, CEPII Mani Shankar AIYAR – Member of the Council of States, India Hippolyte d’ALBIS – Best Young French Economist 2012 Yukiya AMANO – Director General, International Atomic Energy Agency Kym ANDERSON – Professor, University of Adelaide Masahiko AOKI – Professor, Stanford University Jean-Paul BAILLY – CEO, LE GROUPE LA POSTE Mustapha BAKKOURY – Chairman, Moroccan Agency for Solar Energy Patricia BARBIZET – CEO, Artemis Michel BARNIER – Commissioner, European Commission Dominic BARTON – Managing Director, McKinsey Roland BENABOU – Professor, Princeton University Jean BEUNARDEAU – CEO, HSBC France Pascal BLANQUÉ –Deputy CEO, Amundi Cornelius BOERSCH – Member of the Board of Directors, Mountain Partners Gaby BONNAND – Consultant in prospective and social protection, Mutual Insurance Company Jean-Marc BORELLO – CEO, Groupe SOS Claudio BORIO – Deputy Head of the Monetary and Economic Department, Bank for International Settlements Jocelyne BOURGON – President, Public Governance International Stephen BREYER – Justice, US Supreme Court Sylvie BRUNEL – Professor, University of Paris IV Paris-Sorbonne Markus BRUNNERMEIER – Professor, Princeton University Michael BURDA – Professor, Humboldt University in Berlin Bruno CERCLEY – CEO, Rossignol Dominique CERUTTI – Deputy -

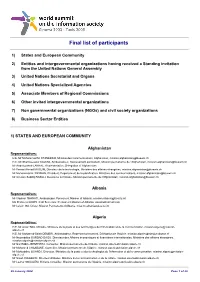

Final List of Participants

Final list of participants 1) States and European Community 2) Entities and intergovernmental organizations having received a Standing invitation from the United Nations General Assembly 3) United Nations Secretariat and Organs 4) United Nations Specialized Agencies 5) Associate Members of Regional Commissions 6) Other invited intergovernmental organizations 7) Non governmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society organizations 8) Business Sector Entities 1) STATES AND EUROPEAN COMMUNITY Afghanistan Representatives: H.E. Mr Mohammad M. STANEKZAI, Ministre des Communications, Afghanistan, [email protected] H.E. Mr Shamsuzzakir KAZEMI, Ambassadeur, Representant permanent, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Mr Abdelouaheb LAKHAL, Representative, Delegation of Afghanistan Mr Fawad Ahmad MUSLIM, Directeur de la technologie, Ministère des affaires étrangères, [email protected] Mr Mohammad H. PAYMAN, Président, Département de la planification, Ministère des communications, [email protected] Mr Ghulam Seddiq RASULI, Deuxième secrétaire, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Albania Representatives: Mr Vladimir THANATI, Ambassador, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Ms Pranvera GOXHI, First Secretary, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Mr Lulzim ISA, Driver, Mission Permanente d'Albanie, [email protected] Algeria Representatives: H.E. Mr Amar TOU, Ministre, Ministère de la poste et des technologies -

The Regional Impact of the Armed Conflict and French Intervention in Mali by David J

Report April 2013 The regional impact of the armed conflict and French intervention in Mali By David J. Francis Executive summary Despite the perceived threat to international peace and security presented by the crisis in Mali, the international community did not act to resolve it for nearly ten months, which allowed Islamists to militarily take control of the whole of northern Mali and impose sharia law. The French military intervention in Mali placed the country at the top of the international political agenda. But the conflict in Mali and the French intervention have wider implications not only for Mali and its neighbours, but also for Africa, the international community, and France’s national security and strategic interests at home and abroad. This report assesses the current crisis, the key actors and the nature of the complex conflict in Mali; the nature and scope of the military, political and diplomatic interventions in Mali by a range of actors; the regional implications of the conflict for the Sahel and West Africa; and the consequences of the French military intervention and its wider implications, including the debate about the risk of the “Afghanistanisation of Mali”. It concludes with policy-relevant recommendations for external countries and intergovernmental actors interested in supporting Mali beyond the immediate military- security stabilisation to long-term peacebuilding, state reconstruction and development. NOREF Report – April 2013 Mali: a complex conflict Mali fighting for a separate independent state. Secondly, Different from the simplistic international media’s portray- there is a political and constitutional crisis occasioned by al of the crisis, the conflict in Mali is a complex and the military overthrow of the democratically elected multidimensional mixture of long-term fundamental government by the army. -

Mali: Avoiding Escalation

MALI: AVOIDING ESCALATION Africa Report N°189 – 18 July 2012 Translation from French TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. THE OBSCURE TWISTS AND TURNS OF ATT’S NORTHERN POLICY ............ 2 A. TUAREG REBELLIONS, THE NATIONAL PACT AND THE ALGIERS ACCORDS ................................... 2 B. LONG-TERM, DEEPLY-ROOTED ESTABLISHMENT OF AQIM IN NORTHERN MALI .......................... 5 C. THE FINAL FAILURE OF ATT’S SECURITY POLICY: THE SPECIAL PROGRAM FOR PEACE, SECURITY AND DEVELOPMENT IN NORTHERN MALI ................................................................... 6 D. FROM THE MNA TO THE MNLA: A REBELLION IN THE MAKING ................................................. 7 III. NOW OR NEVER? THE RESURGENCE OF THE REBELLION ............................ 8 A. THE LIBYAN FACTOR: QADHAFI AND NORTHERN MALI ............................................................... 8 B. THE RISE OF THE MNLA ........................................................................................................... 10 C. IYAD AG GHALI’S THWARTED PERSONAL AMBITIONS AND THE ISLAMIST AGENDA .................. 12 IV. THE FRAGMENTED AND VOLATILE DYNAMICS OF THE REBEL MOVEMENT ................................................................................................................... 13 A. THE LIGHTNING MILITARY CAMPAIGN CONDUCTED BY THE ARMED GROUPS IN -

Mali: the Need for Determined and Coordinated International Action

Policy Briefing Africa Briefing N°90 Dakar/Brussels, 24 September 2012. Translation from French Mali: The Need for Determined and Coordinated International Action indulge in terrorism, jihadism and drug and arms traffick- I. OVERVIEW ing. But the use of force must be preceded by a political and diplomatic effort aiming at separating two different sets In the absence of rapid, firm and coherent decisions at the of issues: those related to communal antagonisms within regional (Economic Community of West African States, Malian society, political and economic governance of the ECOWAS), continental (African Union, AU) and interna- north and religious diversity management; and those re- tional (UN) levels by the end of September, the political, lated to collective security in the Sahel-Sahara region. security, economic and social situation in Mali will dete- Forces of the Malian army and ECOWAS are not capable riorate. All scenarios are still possible, including another of tackling the influx of arms and combatants between military coup and further social unrest in the capital, Libya and northern Mali through southern Algeria and/or which threaten to undermine the transitional institutions northern Niger. Minimal and sustainable security in and create a power vacuum that could allow religious ex- northern Mali cannot be reestablished without the clear tremism and terrorist violence to spread in Mali and be- involvement of Algerian political and military authorities. yond. None of the three actors sharing power – namely interim President Dioncounda Traoré, Prime Minister Following the 26 September high-level meeting on the Cheick Modibo Diarra, and the ex-junta leader, Captain Sahel, expected to take place on the margins of the UN Amadou Sanogo – has sufficient popular legitimacy or General Assembly in New York, Malian actors, their the ability to prevent the aggravation of the crisis.