Computer Program for Diagnosing and Teaching Geographic Me Dic Ine Stephen A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diagnostic Code Descriptions (ICD9)

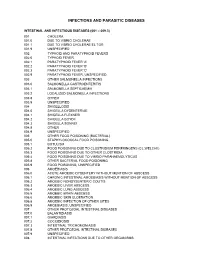

INFECTIONS AND PARASITIC DISEASES INTESTINAL AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES (001 – 009.3) 001 CHOLERA 001.0 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE 001.1 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE EL TOR 001.9 UNSPECIFIED 002 TYPHOID AND PARATYPHOID FEVERS 002.0 TYPHOID FEVER 002.1 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'A' 002.2 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'B' 002.3 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'C' 002.9 PARATYPHOID FEVER, UNSPECIFIED 003 OTHER SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.0 SALMONELLA GASTROENTERITIS 003.1 SALMONELLA SEPTICAEMIA 003.2 LOCALIZED SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.8 OTHER 003.9 UNSPECIFIED 004 SHIGELLOSIS 004.0 SHIGELLA DYSENTERIAE 004.1 SHIGELLA FLEXNERI 004.2 SHIGELLA BOYDII 004.3 SHIGELLA SONNEI 004.8 OTHER 004.9 UNSPECIFIED 005 OTHER FOOD POISONING (BACTERIAL) 005.0 STAPHYLOCOCCAL FOOD POISONING 005.1 BOTULISM 005.2 FOOD POISONING DUE TO CLOSTRIDIUM PERFRINGENS (CL.WELCHII) 005.3 FOOD POISONING DUE TO OTHER CLOSTRIDIA 005.4 FOOD POISONING DUE TO VIBRIO PARAHAEMOLYTICUS 005.8 OTHER BACTERIAL FOOD POISONING 005.9 FOOD POISONING, UNSPECIFIED 006 AMOEBIASIS 006.0 ACUTE AMOEBIC DYSENTERY WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.1 CHRONIC INTESTINAL AMOEBIASIS WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.2 AMOEBIC NONDYSENTERIC COLITIS 006.3 AMOEBIC LIVER ABSCESS 006.4 AMOEBIC LUNG ABSCESS 006.5 AMOEBIC BRAIN ABSCESS 006.6 AMOEBIC SKIN ULCERATION 006.8 AMOEBIC INFECTION OF OTHER SITES 006.9 AMOEBIASIS, UNSPECIFIED 007 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.0 BALANTIDIASIS 007.1 GIARDIASIS 007.2 COCCIDIOSIS 007.3 INTESTINAL TRICHOMONIASIS 007.8 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.9 UNSPECIFIED 008 INTESTINAL INFECTIONS DUE TO OTHER ORGANISMS -

WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 31/05 (2006.01) A61P 31/02 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (21) International Application Number: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, PCT/CA20 14/000 174 DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 4 March 2014 (04.03.2014) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, (25) Filing Language: English OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (26) Publication Language: English SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, (30) Priority Data: ZW. 13/790,91 1 8 March 2013 (08.03.2013) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (71) Applicant: LABORATOIRE M2 [CA/CA]; 4005-A, rue kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, de la Garlock, Sherbrooke, Quebec J1L 1W9 (CA). GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, (72) Inventors: LEMIRE, Gaetan; 6505, rue de la fougere, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, Sherbrooke, Quebec JIN 3W3 (CA). -

Rhinoscleroma in an Immigrant from Egypt: a Case Report

387 BRIEF COMMUNICATION Rhinoscleroma in an Immigrant From Egypt: A Case Report Edgardo Bonacina, MD,∗ Leonardo Chianura, MD, DTM&H,† Maurizio Sberna, MD,‡ Giuseppe Ortisi, MD,§ Giovanna Gelosa, MD,|| Alberto Citterio, MD,‡ Giovanni Gesu, MD,§ and Massimo Puoti, MD† Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jtm/article/19/6/387/1795562 by guest on 23 September 2021 Departments of ∗Pathological Anatomy; †Infectious Diseases; ‡Neuroradiology; §Microbiology, and; ||Otorinolaringoiatry, Niguarda Ca` Granda Hospital, Milano, Italy DOI: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2012.00659.x Rhinoscleroma is a chronic indolent granulomatous infection of the nose and the upper respiratory tract caused by Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis; this condition is endemic to many regions of the world including North Africa. We present a case of rhinoscleroma in a 51-year-old Egyptian immigrant with 1-month history of epistaxis. We would postulate that with increased travel from areas where rhinoscleroma is endemic to other non-endemic areas, diagnosis of this condition will become more common. hough rarely observed, rhinoscleroma has to be nasal fossae and ethmoid sinuses with complete bony T taken into consideration in travelers returning destruction of bilateral nasal turbinates (Figure 1). with ear, nose, and throat presentations, particularly Endoscopic biopsy was performed under local anesthe- after traveling to developing countries or regions where sia. Histopathologic examination revealed numerous this condition is endemic.1,2 foamy macrophages (Mikulicz cells) containing bacteria (Figure 2); no fungal hyphae were found.3 Staphylococcus Case Report aureus and Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis were isolated by culture of the tissue biopsy. A diagnosis of rhinoscle- A 51-year-old Egyptian male immigrant presented on roma was made. -

Unusual Presentation of Rhinoscleroma Dehadaray A1, Patel M2, Kaushik M3, Agrawal D4

Case Report Unusual presentation of Rhinoscleroma Dehadaray A1, Patel M2, Kaushik M3, Agrawal D4 ABSTRACT Rhinoscleroma or respiratory scleroma is a chronic, slowly progressive, inflammatory disease of the upper respiratory tract. Here we present a 35 year old male presenting with unilateral orbital complaints and non- specific findings on radiological examination, diagnosed only by histopathology as Rhinoscleroma. Due to the low incidence of this disease and its rare presentation in this case, diagnosis was a challenge, but outcome was successful. Keywords- Rhinoscleroma, Orbit 1 MS ENT, Professor, 2 MS DNB ENT, Assistant Professor, 3 MS ENT, Professor and Head, 4 PG student, Department of ENT and HNS, Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed University Medical College, Pune-411043. Corresponding Author: Dr. Monika Patel, Assistant Professor, Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed University Medical College, Pune, Maharashtra. Mob: +919028738326 Email: [email protected] 32 The Indian Practitioner q Vol.70 No.11. November 2017 Case Report Introduction hinoscleroma is a chronic progressive, specific granulomatous infectious disease affecting the Rupper respiratory tract associated with Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis infection. It is endemic in Central and South America, Central Africa, Middle East, parts of Europe, India, and Indonesia [1]. It most commonly af- fects the nose [2]. Cases of Rhinoscleroma with invasion into the or- bits are rare, with very few cases reported in litera- ture. Ophthalmologists should also be aware of the Fig 1a Fig 1b disease and the problems in its management. We pres- ent a case of Rhinoscleroma which posed difficulty in with reduced movements in all directions, and vision diagnosing due to its clinical resemblance with other of 6/18. -

Rhinoscleroma

Eur J Rhinol Allergy 2020; 3(2): 53-4 Image of Interest Rhinoscleroma Seepana Ramesh , Satvinder Singh Bakshi Department of ENT and Head & Neck Surgery, AIIMS Mangalagiri, Guntur, India A 22-year-old man presented with a 6-month history of bilateral nasal obstruction and nasal discharge that was associated with intermittent mild episodes of blood-tinged nasal discharge since 2 months. On examination, a pinkish irregular mass was observed in both the nostrils with complete obstruction of the right nostril. Computed tomography revealed a non-en- hanced homogeneous mass in the left frontal, ethmoid, and maxillary sinuses that extended to both the nasal cavities (Figure 1). Histopathology revealed fragments of granulation tissue with inflammatory cells comprising several foamy to vacuolated histiocytes and plasma cells, suggestive of rhinoscleroma (Figure 2). The patient underwent surgical debridement of the mass and received ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily for 6 weeks. He was asymptomatic at 4 months of follow-up. Rhinoscleroma is a chronic granulomatous disease affecting the region between the nose and the subglottis. It is caused by the gram-negative bacillus Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis and spreads by inhalation of contaminated droplets (1). The symptoms depend on the stage of the disease. In the atrophic stage, patients present with fetid nasal dis- charge and crusting, followed by the granulomatous stage, wherein patients develop epistaxis and nasal deformity, secondary to the destruction of the nasal cartilages (1). The final stage is the sclerotic stage, in which patients present with thick dense scars in the nose and upper airway, leading to complete nasal obstruction and even stridor due to laryngeal stenosis (1). -

A Novel Murine Model of Rhinoscleroma Identifies Mikulicz Cells, the Disease Signature, As IL-10 Dependent Derivatives of Inflammatory Monocytes

OPEN TRANSPARENT Research Article ACCESS PROCESS IL-10 controls maturation of Mikulicz cells A novel murine model of rhinoscleroma identifies Mikulicz cells, the disease signature, as IL-10 dependent derivatives of inflammatory monocytes Cindy Fevre1y, Ana S. Almeida2,3y, Solenne Taront2,3, Thierry Pedron2,3, Michel Huerre4, Marie-Christine Prevost5, Aure´lie Kieusseian6,7, Ana Cumano6,7, Sylvain Brisse1, Philippe J. Sansonetti2,3,8,Re´gis Tournebize2,3* Keywords: IL-10; inflammatory Rhinoscleroma is a human specific chronic disease characterized by the monocytes; Klebsiella; Mikulicz cell; formation of granuloma in the airways, caused by the bacterium Klebsiella rhinoscleroma pneumoniae subspecies rhinoscleromatis, a species very closely related to K. pneumoniae subspecies pneumoniae. It is characterized by the appearance of specific foamy macrophages called Mikulicz cells. However, very little is known DOI 10.1002/emmm.201202023 about the pathophysiological processes underlying rhinoscleroma. Herein, we Received September 14, 2012 characterized a murine model recapitulating the formation of Mikulicz cells in Revised January 31, 2013 lungs and identified them as atypical inflammatory monocytes specifically Accepted February 14, 2013 recruited from the bone marrow upon K. rhinoscleromatis infection in a CCR2- independent manner. While K. pneumoniae and K. rhinoscleromatis infections induced a classical inflammatory reaction, K. rhinoscleromatis infection was characterized by a strong production of IL-10 concomitant to the appearance of Mikulicz cells. Strikingly, in the absence of IL-10, very few Mikulicz cells were observed, confirming a crucial role of IL-10 in the establishment of a proper environment leading to the maturation of these atypical monocytes. This is the first characterization of the environment leading to Mikulicz cells maturation and their identification as inflammatory monocytes. -

Lecture 1 ― INTRODUCTION INTO MICROBIOLOGY

МИНИСТЕРСТВО ЗДРАВООХРАНЕНИЯ РЕСПУБЛИКИ БЕЛАРУСЬ УЧРЕЖДЕНИЕ ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ «ГОМЕЛЬСКИЙ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫЙ МЕДИЦИНСКИЙ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ» Кафедра микробиологии, вирусологии и иммунологии А. И. КОЗЛОВА, Д. В. ТАПАЛЬСКИЙ МИКРОБИОЛОГИЯ, ВИРУСОЛОГИЯ И ИММУНОЛОГИЯ Учебно-методическое пособие для студентов 2 и 3 курсов факультета по подготовке специалистов для зарубежных стран медицинских вузов MICROBIOLOGY, VIROLOGY AND IMMUNOLOGY Teaching workbook for 2 and 3 year students of the Faculty on preparation of experts for foreign countries of medical higher educational institutions Гомель ГомГМУ 2015 УДК 579+578+612.017.1(072)=111 ББК 28.4+28.3+28.073(2Англ)я73 К 59 Рецензенты: доктор медицинских наук, профессор, заведующий кафедрой клинической микробиологии Витебского государственного ордена Дружбы народов медицинского университета И. И. Генералов; кандидат медицинских наук, доцент, доцент кафедры эпидемиологии и микробиологии Белорусской медицинской академии последипломного образования О. В. Тонко Козлова, А. И. К 59 Микробиология, вирусология и иммунология: учеб.-метод. пособие для студентов 2 и 3 курсов факультета по подготовке специалистов для зарубежных стран медицинских вузов = Microbiology, virology and immunology: teaching workbook for 2 and 3 year students of the Faculty on preparation of experts for foreign countries of medical higher educa- tional institutions / А. И. Козлова, Д. В. Тапальский. — Гомель: Гом- ГМУ, 2015. — 240 с. ISBN 978-985-506-698-0 В учебно-методическом пособии представлены тезисы лекций по микробиоло- гии, вирусологии и иммунологии, рассмотрены вопросы морфологии, физиологии и генетики микроорганизмов, приведены сведения об общих механизмах функциони- рования системы иммунитета и современных иммунологических методах диагности- ки инфекционных и неинфекционных заболеваний. Приведены сведения об этиоло- гии, патогенезе, микробиологической диагностике и профилактике основных бакте- риальных и вирусных инфекционных заболеваний человека. Может быть использовано для закрепления материала, изученного в курсе микро- биологии, вирусологии, иммунологии. -

Diagnosis One To

Diagnosis One-to-One I9cm I9 Long Desc I10cm I10 Long Desc 0010 Cholera due to vibrio cholerae A000 Cholera due to Vibrio cholerae 01, biovar cholerae 0011 Cholera due to vibrio cholerae el tor A001 Cholera due to Vibrio cholerae 01, biovar eltor 0019 Cholera, unspecified A009 Cholera, unspecified 0021 Paratyphoid fever A A011 Paratyphoid fever A 0022 Paratyphoid fever B A012 Paratyphoid fever B 0023 Paratyphoid fever C A013 Paratyphoid fever C 0029 Paratyphoid fever, unspecified A014 Paratyphoid fever, unspecified 0030 Salmonella gastroenteritis A020 Salmonella enteritis 0031 Salmonella septicemia A021 Salmonella sepsis 00320 Localized salmonella infection, unspecified A0220 Localized salmonella infection, unspecified 00321 Salmonella meningitis A0221 Salmonella meningitis 00322 Salmonella pneumonia A0222 Salmonella pneumonia 00323 Salmonella arthritis A0223 Salmonella arthritis 00324 Salmonella osteomyelitis A0224 Salmonella osteomyelitis 0038 Other specified salmonella infections A028 Other specified salmonella infections 0039 Salmonella infection, unspecified A029 Salmonella infection, unspecified 0040 Shigella dysenteriae A030 Shigellosis due to Shigella dysenteriae 0041 Shigella flexneri A031 Shigellosis due to Shigella flexneri 0042 Shigella boydii A032 Shigellosis due to Shigella boydii 0043 Shigella sonnei A033 Shigellosis due to Shigella sonnei 0048 Other specified shigella infections A038 Other shigellosis 0049 Shigellosis, unspecified A039 Shigellosis, unspecified 0050 Staphylococcal food poisoning A050 Foodborne staphylococcal -

Infectious Diseases of the Philippines

INFECTIOUS DISEASES OF THE PHILIPPINES Stephen Berger, MD Infectious Diseases of the Philippines - 2013 edition Infectious Diseases of the Philippines - 2013 edition Stephen Berger, MD Copyright © 2013 by GIDEON Informatics, Inc. All rights reserved. Published by GIDEON Informatics, Inc, Los Angeles, California, USA. www.gideononline.com Cover design by GIDEON Informatics, Inc No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission from the publisher. Contact GIDEON Informatics at [email protected]. ISBN-13: 978-1-61755-582-4 ISBN-10: 1-61755-582-7 Visit http://www.gideononline.com/ebooks/ for the up to date list of GIDEON ebooks. DISCLAIMER: Publisher assumes no liability to patients with respect to the actions of physicians, health care facilities and other users, and is not responsible for any injury, death or damage resulting from the use, misuse or interpretation of information obtained through this book. Therapeutic options listed are limited to published studies and reviews. Therapy should not be undertaken without a thorough assessment of the indications, contraindications and side effects of any prospective drug or intervention. Furthermore, the data for the book are largely derived from incidence and prevalence statistics whose accuracy will vary widely for individual diseases and countries. Changes in endemicity, incidence, and drugs of choice may occur. The list of drugs, infectious diseases and even country names will vary with time. Scope of Content: Disease designations may reflect a specific pathogen (ie, Adenovirus infection), generic pathology (Pneumonia - bacterial) or etiologic grouping (Coltiviruses - Old world). Such classification reflects the clinical approach to disease allocation in the Infectious Diseases Module of the GIDEON web application. -

PCR-Based Identification of Klebsiella Pneumoniae Subsp

PCR-based identification of Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis, the agent of rhinoscleroma. Cindy Fevre, Virginie Passet, Alexis Deletoile, Valérie Barbe, Lionel Frangeul, Ana Almeida, Philippe Sansonetti, Régis Tournebize, Sylvain Brisse To cite this version: Cindy Fevre, Virginie Passet, Alexis Deletoile, Valérie Barbe, Lionel Frangeul, et al.. PCR-based identification of Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis, the agent of rhinoscleroma.. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, Public Library of Science, 2011, 5 (5), pp.e1052. 10.1371/jour- nal.pntd.0001052. inserm-00691408 HAL Id: inserm-00691408 https://www.hal.inserm.fr/inserm-00691408 Submitted on 26 Apr 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. PCR-Based Identification of Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis, the Agent of Rhinoscleroma Cindy Fevre1, Virginie Passet1, Alexis Deletoile1, Vale´ rie Barbe2, Lionel Frangeul3, Ana S. Almeida4,5, Philippe Sansonetti4,5,Re´gis Tournebize4,5, Sylvain Brisse1* 1 Institut Pasteur, Genotyping of Pathogens and Public Health, Paris, France, 2 CEA-IG, Genoscope, Evry, France, 3 Institut Pasteur, Inte´gration et Analyse Ge´nomique, Paris, France, 4 Institut Pasteur, Unite´ de Pathoge´nie Microbienne Mole´culaire, Paris, France, 5 Unite´ INSERM U786, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France Abstract Rhinoscleroma is a chronic granulomatous infection of the upper airways caused by the bacterium Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. -

Infectious Diseases of the Dominican Republic

INFECTIOUS DISEASES OF THE DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Stephen Berger, MD 2018 Edition Infectious Diseases of the Dominican Republic Copyright Infectious Diseases of the Dominican Republic - 2018 edition Stephen Berger, MD Copyright © 2018 by GIDEON Informatics, Inc. All rights reserved. Published by GIDEON Informatics, Inc, Los Angeles, California, USA. www.gideononline.com Cover design by GIDEON Informatics, Inc No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission from the publisher. Contact GIDEON Informatics at [email protected]. ISBN: 978-1-4988-1759-2 Visit www.gideononline.com/ebooks/ for the up to date list of GIDEON ebooks. DISCLAIMER Publisher assumes no liability to patients with respect to the actions of physicians, health care facilities and other users, and is not responsible for any injury, death or damage resulting from the use, misuse or interpretation of information obtained through this book. Therapeutic options listed are limited to published studies and reviews. Therapy should not be undertaken without a thorough assessment of the indications, contraindications and side effects of any prospective drug or intervention. Furthermore, the data for the book are largely derived from incidence and prevalence statistics whose accuracy will vary widely for individual diseases and countries. Changes in endemicity, incidence, and drugs of choice may occur. The list of drugs, infectious diseases and even country names will vary with time. Scope of Content Disease designations may reflect a specific pathogen (ie, Adenovirus infection), generic pathology (Pneumonia - bacterial) or etiologic grouping (Coltiviruses - Old world). Such classification reflects the clinical approach to disease allocation in the Infectious Diseases Module of the GIDEON web application. -

Report for the Hemodialysis Vascular Access: Standardized Fistula Rate

ESRD Quality Measure Development, Maintenance, and Support Contract Number HHSM-500-2013-13017I Report for the Hemodialysis Vascular Access: Standardized Fistula Rate (SFR) NQF #2977 Submitted to CMS by the University of Michigan Kidney Epidemiology and Cost Center June 21, 2017 Produced by UM-KECC Submitted: 6.21.2017 1 ESRD Quality Measure Development, Maintenance, and Support Contract Number HHSM-500-2013-13017I Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methods ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Overview ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Data Sources ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Outcome Definition .................................................................................................................................. 4 Denominator Definition ............................................................................................................................ 5 Risk Adjustment ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Choosing Adjustment Factors