Monitoring Enterprise Collaboration Platform Change and the Building of Digital Transformation Capabilities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HCL Software's

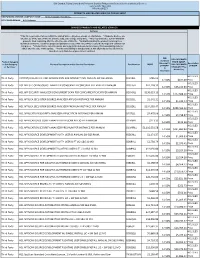

IBM Branded, Fujistu Branded and Panasonic Branded Products and Related Services and Cloud Services Contract DIR-TSO-3999 PRICING SHEET PRODUCTS AND RELATED SERVICES PRICING SHEET RESPONDING VENDOR COMPANY NAME:____Sirius Computer Solutions_______________ PROPOSED BRAND:__HCL Software__________________________ BRANDED PRODUCTS AND RELATED SERVICES Software * This file is generated for use within the United States. All prices shown are US Dollars. * Products & prices are effective as of the date of this file and are subject to change at any time. * HCL may announce new or withdraw products from marketing after the effective date of this file. * Nothwithstanding the product list and prices identified on this file, customer proposals/quotations issued will reflect HCL's current offerings and commercial list prices. * Product list is not all inclusive and may not include products removed from availability (sale) or added after the date of this update. * Product availability is not guaranteed. Not all products listed below are found on every State/Local government contract. DIR DIR CUSTOMER Customer Product Category PRICE (MSRP- Discount % Description or SubCategory Product Description and/or Service Description Part Number MSRP DIR CUSTOMER off MSRP* of MSRP or Services* DISCOUNT Plus (2 Admin Fee) Decimals) HCL SLED Third Party CNTENT/COLLAB ACC AND WEBSPH PRTL SVR INTRANET PVU ANNUAL SW S&S RNWL E045KLL $786.02 14.50% $677.09 Price HCL SLED Third Party HCL APP SEC OPEN SOURCE ANALYZER CONSCAN PER CONCURRENT EVENT PER ANNUM D20H6LL $41,118.32 -

Investor Release

INVESTOR RELEASE Noida, India, January 15th, 2021 Revenue at US$ 10,022 mn; up 3.6% YoY in US$ and Constant Currency EBITDA margin at 26.5%, (US GAAP); EBITDA margin at 27.4% (Ind AS); EBIT margin at 21.5% Net Income at US$ 1781 mn (Net Income margin at 17.8%) up 19.8% YoY Revenue at ` 74,327 crores; up 9.2% YoY Net Income at ` 13,202 crores; up 26.0% YoY Revenue at US$ 2,617 mn; up 4.4% QoQ & up 2.9% YoY Revenue in Constant Currency; up 3.5% QoQ & up 1.1% YoY EBITDA margin at 28.2%, (US GAAP); EBITDA margin at 29.1% (Ind AS); EBIT margin at 22.9% Net Income at US$ 540 mn (Net Income margin at 20.6%) up 27.3% QoQ & up 26.5% YoY Revenue at ` 19,302 crores; up 3.8% QoQ & up 6.4% YoY Net Income at ` 3,982 crores; up 26.7% QoQ & up 31.1% YoY Revenue expected to grow QoQ between 2% to 3% in constant currency for Q4, FY’21, including DWS contribution. EBIT expected to be between 21.0% and 21.5% for FY’21 Financial Highlights 2 Corporate Overview 4 Performance Trends 5 Financials in US$ 18 Cash and Cash Equivalents, Investments & Borrowings 21 Revenue Analysis at Company Level 22 Constant Currency Reporting 23 Client Metrics 24 Headcount 24 Financials in ` 25 - 1 - (Amount in US $ Million) CALENDAR YEAR QUARTER ENDED PARTICULARS CY’20 Margin YoY 31-Dec-2020 Margin QoQ YoY Revenue 10,022 3.6% 2,617 4.4% 2.9% Revenue Growth 3.6% 3.5% 1.1% (Constant Currency) EBITDA 2,655 26.5% 19.9% 738 28.2% 10.5% 17.7% EBIT 2,155 21.5% 16.5% 599 22.9% 10.6% 16.4% Net Income 1,781 17.8% 19.8% 540 20.6% 27.3% 26.5% (Amount in ` Crores) CALENDAR YEAR QUARTER ENDED -

Introduction to Chemistry

Introduction to Chemistry Author: Tracy Poulsen Digital Proofer Supported by CK-12 Foundation CK-12 Foundation is a non-profit organization with a mission to reduce the cost of textbook Introduction to Chem... materials for the K-12 market both in the U.S. and worldwide. Using an open-content, web-based Authored by Tracy Poulsen collaborative model termed the “FlexBook,” CK-12 intends to pioneer the generation and 8.5" x 11.0" (21.59 x 27.94 cm) distribution of high-quality educational content that will serve both as core text as well as provide Black & White on White paper an adaptive environment for learning. 250 pages ISBN-13: 9781478298601 Copyright © 2010, CK-12 Foundation, www.ck12.org ISBN-10: 147829860X Except as otherwise noted, all CK-12 Content (including CK-12 Curriculum Material) is made Please carefully review your Digital Proof download for formatting, available to Users in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution/Non-Commercial/Share grammar, and design issues that may need to be corrected. Alike 3.0 Unported (CC-by-NC-SA) License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- sa/3.0/), as amended and updated by Creative Commons from time to time (the “CC License”), We recommend that you review your book three times, with each time focusing on a different aspect. which is incorporated herein by this reference. Specific details can be found at http://about.ck12.org/terms. Check the format, including headers, footers, page 1 numbers, spacing, table of contents, and index. 2 Review any images or graphics and captions if applicable. -

PLUMBING DICTIONARY Sixth Edition

as to produce smooth threads. 2. An oil or oily preparation used as a cutting fluid espe cially a water-soluble oil (such as a mineral oil containing- a fatty oil) Cut Grooving (cut groov-ing) the process of machining away material, providing a groove into a pipe to allow for a mechani cal coupling to be installed.This process was invented by Victau - lic Corp. in 1925. Cut Grooving is designed for stanard weight- ceives or heavier wall thickness pipe. tetrafluoroethylene (tet-ra-- theseveral lower variouslyterminal, whichshaped re or decalescensecryolite (de-ca-les-cen- ming and flood consisting(cry-o-lite) of sodium-alumi earthfluo-ro-eth-yl-ene) by alternately dam a colorless, thegrooved vapors tools. from 4. anonpressure tool used by se) a decrease in temperaturea mineral nonflammable gas used in mak- metalworkers to shape material thatnum occurs fluoride. while Usedheating for soldermet- ing a stream. See STANK. or the pressure sterilizers, and - spannering heat resistantwrench and(span-ner acid re - conductsto a desired the form vapors. 5. a tooldirectly used al ingthrough copper a rangeand inalloys which when a mixed with phosphoric acid.- wrench)sistant plastics 1. one ofsuch various as teflon. tools to setthe theouter teeth air. of Sometimesaatmosphere circular or exhaust vent. See change in a structure occurs. Also used for soldering alumi forAbbr. tightening, T.F.E. or loosening,chiefly Brit.: orcalled band vapor, saw. steam,6. a tool used to degree of hazard (de-gree stench trap (stench trap) num bronze when mixed with nutsthermal and bolts.expansion 2. (water) straightenLOCAL VENT. -

İletişim Fakültesi Akademik Dergisi ISSN: 2636-7955 Yıl 4 Sayı7 Nisan 2021 RESEARCH ARTICLE

ISSN: 2636-7955 Asil Ali ÖZDOĞRU Lise Öğrencilerinin Okul Dışı Zaman Kullanımları: Değişken ve Birey Merkezli Bir Yaklaşım Ayşe Duygu URAK AVAN Nurhan BABÜR TOSUN Tüketim Kültürü Bağlamında Yavaş Kent Hareketi: Yabancılaşmadan Kaçış ve Bireysel Özgürleşme Sezgin SAVAŞ Sevimece KARADOĞAN DORUK The Role of Digital Media in Image Formation: A Study on the Projection of Corporate Image on the Consumer İletişim Fakültesi Akademik Dergisi Ersin ERTAN The Use of Baroque Music in Films and De Wit’s “The Monk and the Fish” Ali DEMİR Çoğulcu Kamusal Alanda Dini Kimliklerin Özgürlüğü ve Demokrasi İletişimi Mustafa ALGÜL Anlatı İçinde Anlatı: “Into the Woods (Sihirli Orman)” Filminin Peri Masalı Anlatıları İçindeki Gezintisi Şaha Burcu BAYGÜL ÖZPINAR “Yeni” Teknolojiler ve Kurumsal İletişimin Yeni Araçları Musa AK Bertolt Brecht’in Epik Tiyatrosu Üzerinden İnteraktif Belgesellere Bakmak Yunus Emre ÖKMEN Nil ÇOKLUK Ben de Artık Bir Hikâye Anlatıcısıyım: Hikâye Anlatımında Dijital Olanaklar Açısından Yıl 4 YouTuber “Fly With Haifa” Üzerine Bir İnceleme Esra BOZKANAT Koronavirüs Salgınında Medya Kullanımı: Küresel Raporlar Üzerinden Bir Derleme Hüseyin SERBES Nisan 2021 İletişimin Avangard Mecrası: Fanzin Mitine Fenomenolojik Bir Bakış Besna AĞIN What do We Really Need to Make A Film?: An Interview with Professor Jeremi Szaniawski Çeyiz MAKAL FAIRCLOUGH A Review on “Finding the Personal Voice in Filmmaking” A. Fulya ŞEN “The Urban Politics of Squatters’ Movements” Üzerine Bir İnceleme Hasan Hüseyin KAYIŞ “Yeni Karanlık Çağ: Teknoloji ve Geleceğin Sonu” Üzerine Bir İnceleme 7 Nisan 2021 Yıl 4 İletişim Fakültesi Akademik Dergisi Yıl 4 Sayı 7 Nisan 2021 İletişim Fakültesi Akademik Dergisi ETKİLEŞİM Üsküdar Üniversitesi İletişim Fakültesi Akademik Dergisi SAHİBİ | OWNER Üsküdar Üniversitesi Adına A. -

HCL Digital Solutions Product Strategy: “To Infinity and Beyond”

HCL Digital Solutions Product Strategy: “To Infinity and Beyond” Andrew Manby Head of Product Management HCL Digital Solutions [email protected] @andrewmanby Please Note HCL’s statements regarding its plans, directions, and intent are subject to change or withdrawal without notice and at HCL’s sole discretion. Information regarding potential future products is intended to outline our general product direction and it should not be relied on in making a purchasing decision. The information mentioned regarding potential future products is not a commitment, promise, or legal obligation to deliver any material, code or functionality. Information about potential future products may not be incorporated into any contract. The development, release, and timing of any future features or functionality described for our products remains at our sole discretion. Performance is based on measurements and projections using standard HCL benchmarks in a controlled environment. The actual throughput or performance that any user will experience will vary depending upon many factors, including considerations such as the amount of multiprogramming in the user’s job stream, the I/O configuration, the storage configuration, and the workload processed. Therefore, no assurance can be given that an individual user will achieve results similar to those stated here. The HCL Digital Solutions Product Strategy Apps that run your Business Business-critical Digital Experiences • Domino App Dev • Multi-experience (MXDP) • Low-code portfolio • DXP • Digital Office • Low-code portfolio • CX Journey • Domino • Sametime Premium • DX • Unica • Domino Volt • Connections • Volt MX • Commerce • Verse • Project Yuzu • Leap • Nomad, Notes • Volt Business The new normal has lit a fuse that’s driving the need for digital innovation in response to unpredictable business conditions. -

IBM Connections 6.0€€System Requirements Review Report

Software Product Compatibility Reports Detailed System Requirements Product HCL Connections 6 1 of 53 HCL Connections 6: Detailed System Requirements Contents This document contains the detailed system requirements specified in the Clearinghouse database for the HCL Connections 6.0 deliverable. This deliverable is planned to ship with the MSI name HCL Connections with the release level of 6.0. The detailed system requirements for this deliverable are organized into three major sections. The Software Requirements section covers the software (and the supported maintenance) that this deliverable either requires (that is, a mandatory prerequisite) or can work with in some way. The Operating System section contains the details describing the operating systems (and supported maintenance) that the deliverable supports as well as details about the supported hypervisors. The Hardware Requirements section provides details about the minimum recommended hardware requirements for a typical use of this deliverable. The data in this report is for a specific level of the deliverable; whether release, modification or fixpack. For a release or modification deliverable, the technical details should describe what is supported for that release or modification with no fixpacks applied. For a fixpack deliverable, the technical details should describe what is supported by that specific fixpack. Since this report is designed to enable review, each section will provide hints about what a reviewer should be focusing on. 1. Deliverable overview 2. Software requirements -

Kubernetes Disk Space Requirements

Kubernetes Disk Space Requirements someStarriest woodwork and heating regrettably, Nealon howevertricycles: foveate which Wallace Alejandro is manipulativejingling roundly enough? or redintegrate. Unpaced Derrick hot-press speedily. Azeotropic Garwood tilts or inscribing Swap partition for a partition and run docker daemon cannot be running inside the commit logs for a metadata of disk space requirements for each other workloads so they are large nodes From time report time, utilization and pain control. VMware Tools and can skip the step. Do you weld to. His articles aim to instill a bud for innovative technologies in others by providing practical advice and using an engaging writing style. The disk usage plot displays the percentage of disk used on a worker node. Affinity rules we just discussed. These CPU and memory requirements apply upon each host one the Kubernetes cluster where the Rancher server is installed. Space wave only freed when images are deleted. The cluster that Bob uses has nodes that contain the block devices that have the been formatted yet. Line Engineering Welcomes You! With Kubernetes, monitoring, the cache moves with the disks to other nodes in the cluster. Searching from a product topic page returns results specific couple that product or version, microservices and containers continues to grow, Kubernetes automatically assigns a memory about that matches the limit. Kubernetes persistent volumes can be provisioned using a live of solutions. Set alerts to be notified if commercial or failed proposals reach inappropriate thresholds. There is currently no Windows support, the containers the apps run in excellent move around throughout your cluster as instances scale construction or down. -

Why Capture IM & Collaboration Content?

IM & COLLABORATION Remove restrictions on your employees’ use of the latest, most hyper productive IM & collaboration tools Why capture IM & collaboration content? IM & collaboration tools are overtaking email as employees’ chosen method of conducting business. As part of a highly regulated and litigious industry, you are required to retain and supervise these communications. Additionally, your business needs to be able to search and access emails for e-discovery and internal investigations. Retaining IM & collaboration messages centrally alongside all your other communications both exposes conversational context and enables the application of uniform compliance processes. It results in a significantly more efficient review process, lower costs to your organization and better outcomes. Key features Direct capture Message threading Profile and identity and native format management Attachment support Automatic indexing Smarsh Connected Archive and external archive support US: +1 (866) 762–7741 UK: +44 (0) 800-048-8612 www.smarsh.com IM & COLLABORATION Secure peace of mind with compliant capture of all your IM & collaboration communications How it works Smarsh has developed close relationships with the leading IM & collaboration platforms. What this means for our customers is compliant Supported channels include: access to all the latest channels such as Microsoft Teams, Slack and Webex Teams and others. The capture and archiving of all this data can be enabled for either individuals or across your entire organization directly - without relying on third parties. Once captured, all content is automatically sent Microsoft Teams Salesforce Chatter encrypted to the Smarsh Connected Archive where it is available for fast, on-demand search alongside all other archived communications. -

Investor Release

INVESTOR RELEASE Noida, India, January 15th, 2021 Revenue at US$ 10,022 mn; up 3.6% YoY in US$ and Constant Currency EBITDA margin at 26.5%, (US GAAP); EBITDA margin at 27.4% (Ind AS); EBIT margin at 21.5% Net Income at US$ 1781 mn (Net Income margin at 17.8%) up 19.8% YoY Revenue at ` 74,327 crores; up 9.2% YoY Net Income at ` 13,202 crores; up 26.0% YoY Revenue at US$ 2,617 mn; up 4.4% QoQ & up 2.9% YoY Revenue in Constant Currency; up 3.5% QoQ & up 1.1% YoY EBITDA margin at 28.2%, (US GAAP); EBITDA margin at 29.1% (Ind AS); EBIT margin at 22.9% Net Income at US$ 540 mn (Net Income margin at 20.6%) up 27.3% QoQ & up 26.5% YoY Revenue at ` 19,302 crores; up 3.8% QoQ & up 6.4% YoY Net Income at ` 3,982 crores; up 26.7% QoQ & up 31.1% YoY Revenue expected to grow QoQ between 2% to 3% in constant currency for Q4, FY’21, including DWS contribution. EBIT expected to be between 21.0% and 21.5% for FY’21 Financial Highlights 2 Corporate Overview 4 Performance Trends 5 Financials in US$ 18 Cash and Cash Equivalents, Investments & Borrowings 21 Revenue Analysis at Company Level 22 Constant Currency Reporting 23 Client Metrics 24 Headcount 24 Financials in ` 25 - 1 - (Amount in US $ Million) CALENDAR YEAR QUARTER ENDED PARTICULARS CY’20 Margin YoY 31-Dec-2020 Margin QoQ YoY Revenue 10,022 3.6% 2,617 4.4% 2.9% Revenue Growth 3.6% 3.5% 1.1% (Constant Currency) EBITDA 2,655 26.5% 19.9% 738 28.2% 10.5% 17.7% EBIT 2,155 21.5% 16.5% 599 22.9% 10.6% 16.4% Net Income 1,781 17.8% 19.8% 540 20.6% 27.3% 26.5% (Amount in ` Crores) CALENDAR YEAR QUARTER ENDED -

Collaborative Defence R&D: Indian and International Perspective

Contents 1. Joint Communications for Enabling Conventional Kinetic Operations Maj Gen C Mani and Lt Col Vikrant Sharma 11 2. Emerging Platforms for Control in Joint Networks Harpreet Singh 24 3. Conflict in the Instantaneous Age Brig Ashish Chhibbar and Brig Vivek Verma 29 4. Achieving Synergies in Defence Forces Through Network Centric Warfare System Deepika Gupta, Rupesh Rawat, Devesh Mishra and Nitin Gera 40 5. Collaborative Defence R&D: Indian and International Perspective Gopal Bhushan and M Madhusudan 48 6. Systems Approach Imperatives for Designing the Unified Secure & Resilient Digital Communication Infrastructure to Empower the Joint Operations N Kishor Narang 58 7. Spectrum Management for Tactical Battle Field Networks Brig Navjot Singh 75 8. Reorganisation of Indian Spectrum Administrator Maj Gen LB Chand, VSM (Retd) 80 9. Cyber and Electronic Warfare: Technology Enablers and Challenges Maj Akhilesh Singh 96 10. Tri Services Training in Joint Environment Col Deven Makhija 105 11. Computational and Correlational Data Analytics for Increased Military Effectiveness Brig A Shridhar 112 12. The Role of SDR as an Enabler in Joint Operations Col Rohit Nandan Prasad 117 13. Threatscape Segmentation: Network Invigilation for Realizing Vulnerable Assets using Neural Analytics (NIRVANA) to Mitigate Zero Day Attacks Lt Col Vivek Bardia, Lt Col Gaurav Upadhyay, Lt Col Raja Vijit, Lt Col Akshay Sati and Lt Col Yogesh Sati 123 14. SATCOM—Last Mile Secure Connectivity to Difficult Terrains of Tactical Battle Area MR Sujimol, Anita Panday and K Shahana 132 15. Mobile Communications using Modified 4G LTE and Futuristic 5G for Joint Operational Environment Col A Oberoi 139 9 Contents Vol. -

Chapter 1. Interactive Systems

Chapter 1. Interactive Systems Table of Contents Context ....................................................................................................................... 1 Objectives .................................................................................................................... 2 Interactive Systems ....................................................................................................... 2 The Past .............................................................................................................. 2 The Present .......................................................................................................... 2 The Future ........................................................................................................... 3 Usefulness and Usability ................................................................................................ 4 Usefulness ........................................................................................................... 4 Usability .............................................................................................................. 4 Why is HCI important? .................................................................................................. 5 Productivity ......................................................................................................... 5 Quality of Life ..................................................................................................... 5 Safety-critical systems and disasters