Stem-Cell Scientists Mourn Loss of Brain Engineer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

With His Knack for Knowing What Stem Cells Want, Yoshiki Sasai Has Grown an Eye and Parts of a Brain in a Dish

THE BRAINMAKER BY DAVID CYRANOSKI With his knack for knowing what stem cells want, Yoshiki Sasai has grown an eye and parts of a brain in a dish. n December 2010, Robin Ali became suddenly coaxing neural stem cells to grow into elaborate structures. excited by the usually mundane task of reviewing As well as the optic cup1, he has cultivated the delicate tissue a scientific paper. “I was running around my room, layers of the cerebral cortex2 and a rudimentary, hormone- I waving the manuscript,” he recalls. The paper making pituitary gland3. He is now well on the way to growing described how a clump of embryonic stem cells had grown a cerebellum4 — the brain structure that coordinates move- into a rounded goblet of retinal tissue. The structure, called ment and balance. “These papers make for the most addictive an optic cup, forms the back of the eye in a growing embryo. series of stem-cell papers in recent years,” says Luc Leyns, a But this one was in a dish, and videos accompanying the paper stem-cell scientist at the Free University of Brussels. showed the structure slowly sprouting and blossoming. For Sasai’s work is more than tissue engineering: it tackles HANS SAUTTER Ali, an ophthalmologist at University College London who questions that have puzzled developmental biologists for has devoted two decades to repairing vision, the implications decades. How do the proliferating stem cells of an embryo were immediate. “It was clear to me it was a landmark paper,” organize themselves seamlessly into the complex structures he says. -

Acid Bath Offers Easy Path to Stem Cells

NEWS IN FOCUS that the pluripotent cells were converted mature cells and not pre-existing pluripotent cells. So she made pluripotent cells by stressing T cells, a type of white blood cell whose maturity is clear from a rearrangement that its genes undergo OBOKATA HARUKO during development. She also caught the con- version of T cells to pluripotent cells on video. Obokata called the phenomenon stimulus- triggered acquisition of pluripotency (STAP). The results could fuel a long-running debate. For years, various groups of scientists have reported finding pluripotent cells in the mam- malian body, such as the multipotent adult pro- genitor cells described4 by Catherine Verfaillie, a molecular biologist then at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. But others have had difficulty reproducing such findings. Obokata started the current project in the laboratory of tissue engineer Charles Vacanti at Harvard Uni- versity in Cambridge, Massachusetts, by looking at cells that Vacanti’s group thought to be pluri- potent cells isolated from the body5. But her A mouse embryo injected with cells made pluripotent through stress, tagged with a fluorescent protein. results suggested a different explanation: that pluripotent cells are created when the body’s REGENERATIVE MEDICINE cells endure physical stress. “The generation of these cells is essentially Mother Nature’s way of responding to injury,” says Vacanti, a co-author of the latest papers2,3. Acid bath offers easy One of the most surprising findings is that the STAP cells can also form placental tissue, something that neither iPS cells nor embryonic path to stem cells stem cells can do. -

Curriculum Vitae Kenji Mizuseki, M.D., Ph.D

Curriculum Vitae Kenji Mizuseki, M.D., Ph.D. Personal Information Office address Allen Institute for Brain Science 551 N 34th Street, Seattle, WA 98103, U.S.A. Office phone 1-206-548-8417 Cell phone 1-973-202-4325 E-mail [email protected] [email protected] Web http://www.alleninstitute.org/our-institute/our-team/profiles/kenji-mizuseki Research Experience Senior Scientist, September 2012 – present Allen Institute for Brain Science, WA, U.S.A Research Assistant Professor, March 2012 – August 2012 Neuroscience Institute, New York University, NY, U.S.A. Advisor: Prof. György Buzsáki Research Assistant Professor, March 2009 – March 2012 Center for Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience, Rutgers University, NJ, U.S.A. Advisor: Prof. György Buzsáki Post-doctoral Fellow, April 2004 – March 2009 Center for Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience, Rutgers University, NJ, U.S.A. Advisor: Prof. György Buzsáki Staff Research Scientist, March 2002 – March 2004 Center for Developmental Biology, RIKEN, Kobe, Japan Advisor: late Dr. Yoshiki Sasai, Group Leader Research Fellow, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, April 2000 – February 2002 Institute for Frontier Medical Sciences, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan Advisor: late Prof. Yoshiki Sasai Page 1 of 8 Kenji Mizuseki Education Ph.D. in Medicine, March 2000 Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan Advisors: Prof. Shigetada Nakanishi and late Associate Prof. Yoshiki Sasai M.D., March 1996 Faculty of Medicine, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan Publications Diba,K., Amarasingham. A., Mizuseki,K., and Buzsáki, G. (2014). Millisecond timescale synchrony among hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 34, 14984-14994. Schomburg, E.W., Fernández-Ruiz, A., Mizuseki, K., Berényi, A., Anastassiou, C.A., Koch, C., and Buzsáki, G. -

March 30, 2012, NIH Record, Vol. LXIV, No. 7

MARCH 30, 2012 The Second Best Thing About Payday VOL. LXIV, NO. 7 Brace for More BRAC-Related Commuting Challenges ou may have noticed some roadway changes to support the integration of Wal- ter Reed Army Medical Center with the National Naval Medical Center. Already ABOVE · What is IT? See p. 2 for hints. Y we experience long waits to exit onto Rockville Pike in the evenings and additional congestion in the mornings, adding time and frustration to our daily commute. For features the estimated 18,000 NIH staff who work on the Bethesda campus along with our patients and visitors, it will only get worse before it gets better. 1 Roadway construction to support Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) for the new NIH Urges Employees to Explore Alternatives to Car Commutes Walter Reed National Military Medical Center started earlier this month. Ex- 3 pect additional delays related to con- Collins To Keynote TEDMED Talks struction of new turn lanes and par- 5 tial widening of Wisconsin Ave., Jones ‘Feedback’ Features Child Care Bridge Rd., and Cedar Ln. Portions of Question Rockville Pike and Connecticut Ave. in 12 Bethesda and North Chevy Chase will NIH’s CFC Success Celebrated see construction work for 3 years. see brac, page 6 One of the busiest intersections in the nation— departments Rockville Pike at Cedar Lane— will get busier. Former NIH Colleagues Kuller Outlines Difficulties in Fighting Briefs 2 Daytons Collaborate on Novel of Iran The Obesity Epidemic Feedback 5 By Rich McManus By Trisha Comsti Digest 9 Dr. Andrew Imbrie Dayton, a senior investi- The rise and spread of obesity in the United Milestones 10 gator at FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation States is a serious concern for everyone, young Seen 12 and Research in Bldg. -

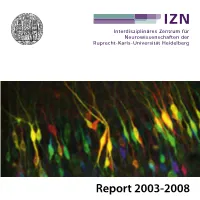

Report 2003-2008 Report 2003-2008 Editors

Report 2003-2008 Report 2003-2008 Editors: The Board of Directors Interdisciplinary Center for Neurosciences (IZN) University of Heidelberg Im Neuenheimer Feld 364 D-69120 Heidelberg www.izn.uni-heidelberg.de Concept, Coordination and Editorial Office: Dipl.-Biol. Ute Volbehr Susanne Kilian M.A. Cover illustration by Simon Wiegert, Neurobiology, IZN: Dr. Otto Bräunling Depth-coded maximum z-projection of hippocampal CA1- neurons expressing Dronpa-labelled ERK1. The colour-spectrum from violet to red was used to artificially colour-code the position Production and Layout: of neurons in z-direction. Rolf Nonnenmacher, Dipl. Designer (FH) Image Sources: Sven Weimann Images were provided by the IZN Investigators and the Heidelberg University Hospital Media Center, the University of Heidelberg, the German Cancer Research Institute, Photolab/European Printed by: Molecular Biology Laboratory, Max Planck Institute for Medical Research, and Central Institute for Mental Health Mannheim. CITY-DRUCK HEIDELBERG 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents Boards 5 Thomas Kuner 93 Siegfried Mense 96 Research groups / IZN-Investigators 6 Andreas Meyer-Lindenberg 99 Concept and strucure of the IZN 9 Hannah Monyer 101 Appointments 14 Ulrike Müller 104 Christof Niehrs 107 Awards 16 Sabina Pauen 110 IZN Funding and grant giving bodies 18 Gabriele Elisabeth Pollerberg 113 Gudrun Rappold 116 Guest scientists 19 André Rupp 119 Collaborations 21 Martin Schmelz 122 Research Groups 35 Gerhard Schratt 124 Detlev Arendt 36 Christoph Schuster 127 Hilmar Bading 39 Günther Schütz 130 Dusan Bartsch 42 Markus Schwaninger 134 Martin Bohus 45 Peter H. Seeburg 136 Francesca Ciccolini 48 Horst Simon 137 Andreas von Deimling 51 Thomas Söllner 140 Winfried Denk 54 Rainer Spanagel 143 Andreas Draguhn 55 Hartwig Spors 147 Uwe Ernsberger 58 Rolf Sprengel 150 Thomas Euler 61 Kerry Tucker 153 Christian Fiebach 64 Klaus Unsicker 156 Herta Flor 67 Wolfgang Wick 159 Stephan Frings 70 Otmar D. -

Minimization of Exogenous Signals in ES Cell Culture Induces Rostral Hypothalamic Differentiation

Minimization of exogenous signals in ES cell culture induces rostral hypothalamic differentiation Takafumi Wataya*†, Satoshi Ando‡, Keiko Muguruma*, Hanako Ikeda*, Kiichi Watanabe*, Mototsugu Eiraku*, Masako Kawada*, Jun Takahashi†, Nobuo Hashimoto†, and Yoshiki Sasai*§¶ *Organogenesis and Neurogenesis Group and ‡Division of Human Stem Cell Technology, RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology, Kobe 650-0047, Japan; and Departments of †Neurosurgery and §Medical Embryology, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan Edited by Shigetada Nakanishi, Osaka Bioscience Institute, Osaka, Japan, and approved June 6, 2008 (received for review March 28, 2008) Embryonic stem (ES) cells differentiate into neuroectodermal progen- 4, 6, 8, 11), contains bioactive (growth) factors such as a high itors when cultured as floating aggregates in serum-free conditions. concentration of insulin (6.7 g/ml in 10% KSR) and lipid-rich Here, we show that strict removal of exogenous patterning factors albumin partially purified from bovine serum (6) (PCT patent no. during early differentiation steps induces efficient generation of WO 98/30679). rostral hypothalamic-like progenitors (Rax؉/Six3؉/Vax1؉) in mouse In this report, we show that ES cell-derived neuroectodermal ES cell-derived neuroectodermal cells. The use of growth factor-free cells robustly differentiate into cells expressing regional markers of chemically defined medium is critical and even the presence of the embryonic rostral hypothalamus when cultured in a strictly exogenous insulin, which is commonly used in cell culture, strongly chemically defined medium (CDM; growth factor-free chemically inhibits the differentiation via the Akt-dependent pathway. The ES defined medium is gfCDM hereafter), free of KSR and other .cell-derived Rax؉ progenitors generate Otp؉/Brn2؉ neuronal precur- growth factors including insulin sors (characteristic of rostral–dorsal hypothalamic neurons) and sub- sequently magnocellular vasopressinergic neurons that efficiently Results release the hormone upon stimulation. -

Yoshiki Sasai (1962–2014) Stem-Cell Biologist Who Decoded Signals in Embryos

COMMENT OBITUARY Yoshiki Sasai (1962–2014) Stem-cell biologist who decoded signals in embryos. ow does a fertilized egg — a single which the brain’s cerebral cortex arises. By medicine. He thought that it could be cell — produce the myriad special carefully adding growth factors, he coaxed pushed even further, thinking of ways to ized cells that assemble into three- the organoids into forming the front or the generate multiple brain structures in vitro Hdimensional tissues and functioning back of the cortex. These advances provide that could become interconnected. organs? This fundamental secret has capti powerful tools for understanding healthy Sasai obtained his MD in 1986 and his vated generations of embryologists. Using and aberrant human brain development. PhD in 1993 from Kyoto University, where creative culture conditions and unmatched The methods that he developed may one he trained as a molecular biologist in the insight into the action of biological signals day be used to make replacement cells to laboratory of neuroscientist Shigetada that govern tissue development, Yoshiki treat currently uncurable diseases. Nakanishi. He then went to the Univer Sasai found ways to mimic these sity of California, Los Angeles, and mysterious processes in the labora worked with embryologist Edward tory. He leaves a legacy of remark De Robertis to discover chordin, able discoveries that expand the one of the key early inducers in frontiers of stem-cell research and the formation of the nervous sys tissue regeneration. tem. In 1996, Sasai moved back to Yoshiki struck me as a happy Kyoto University, where he began scientist. He spoke softly and with a his extraordinary work mimicking unique smile as he described Japanese embryonic development in a dish. -

Stem Cells in Neuroendocrinology

Research and Perspectives in Endocrine Interactions Donald Pfaff Yves Christen Editors Stem Cells in Neuroendocrinology Research and Perspectives in Endocrine Interactions More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/5241 Donald Pfaff • Yves Christen Editors Stem Cells in Neuroendocrinology Editors Donald Pfaff Yves Christen Department of Neurobiology & Behavior Fondation Ipsen The Rockefeller University Boulogne Billancourt New York, New York France USA ISSN 1861-2253 ISSN 1863-0685 (electronic) Research and Perspectives in Endocrine Interactions ISBN 978-3-319-41602-1 ISBN 978-3-319-41603-8 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-41603-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016946609 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016. This book is published open access. Open Access This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, a link is provided to the Creative Commons license and any changes made are indicated. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the work’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work’s Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt or reproduce the material. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. -

Top Japan Lab Dismisses Ground-Breaking Stem Cell Study 26 December 2014, by Kyoko Hasegawa

Top Japan lab dismisses ground-breaking stem cell study 26 December 2014, by Kyoko Hasegawa cells had been added in the process of the research, hammering Obokata's contention that she had found an easier way to generate new stem cells in the lab. "But we can't conclude whether the mixing was done on purpose or by mistake nor can we conclude who did it," probe team chief Isao Katsura, head of the National Institute of Genetics, told a news briefing in Tokyo. In January, Riken trumpeted Obokata's simple method to re-programme adult cells to work like stem cells. The study was top news in Japan, where the photogenic Obokata, a Harvard-trained scientist, Haruko Obokata, 31, a researcher at Japan's Riken became a phenomenon. institute, wipes away tears during a press conference in Osaka, western Japan, on April 9, 2014 Japan's top research institute on Friday hammered the final nail in the coffin of what was once billed as a ground-breaking stem cell study, dismissing it as flawed and saying the work could have been fabricated. The revelations come a week after a young researcher at the centre of the scandal, which has rocked the country's scientific establishment, said she would resign after failing to reproduce the successful conversion of an adult cell into a stem cell-like state, known as "STAP" cells. The failure marked a stunning fall from grace for Yoshiki Sasai, supervisor of Haruko Obokata, a scientist 31-year-old Haruko Obokata, whose co-researcher at Riken institute, answers questions during a press committed suicide amid the embarrassing scandal conference in Tokyo, on April 16, 2014 that prompted respected science journal Nature to retract an article detailing the research. -

Japanese Scientist Resigns As 'STAP' Stem-Cell Method Fails : Nature

Japanese scientist resigns as 'STAP' stem-cell method fails Haruko Obokata caused a sensation earlier this year with papers, now discredited, that claimed a simple method for creating stem cells. Alison Abbott 19 December 2014 JIJI PRESS/AFP/Getty A RIKEN team announced on 19 December that it was unable to reproduce Obokata's controversial results. Haruko Obokata, the stem-cell biologist whose papers caused a sensation earlier this year before being retracted, has resigned from the RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology in Kobe, Japan. Her emotional resignation letter was posted on RIKEN’s website on 19 December alongside results of the organization’s own investigation, which failed to confirm her claims of a simple method to create pluripotent stem cells. Such cells are scientifically valuable because they can develop into most other cells types, from brain to muscle. But they are difficult to make. Obokata’s method — known as stimulus-triggered acquisition of pluripotency, or STAP — was published in Nature in January1, 2. However, the results immediately came under suspicion, and the papers were retracted in July. A few weeks later, one of the paper’s co-authors, Yoshiki Sasai, took his own life. Obokata wrote she could not “find words enough to apologize... for troubling so many people at RIKEN and other places”. In an accompanying statement, RIKEN president Ryoji Noyori wrote that Obokata had been subject to extreme stress over the affair, and that in accepting her resignation he hoped to save her "further mental burden". Nature doi:10.1038/nature.2014.16631 References 1. Obokata, H. -

2002 Annual Report 2002 Annual Report

RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology 2002 Annual Report 2002 Annual Report http://www.cdb.riken.go.jp CENTER FOR DEVELOPMENTAL BIOLOGY (CDB) 2-2-3 MINATOJIMA-MINAMIMACHI, CHUO-KU KOBE, 650-0047 JAPAN PHONE: +81-78-306-0111 FAX: +81-78-306-0101 EMAIL: [email protected] Production Text Douglas Sipp Content Development Naoki Namba Douglas Sipp Design TRAIS K. K. Photography Yutaka Doi On The Cover Distribution of the ERM proteins ezrin (green) and moesin (red) in the forelimb bud of the mouse embryo. Photo: Shigenobu Yonemura All contents copyright (c) RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology, 2003. Printed in Japan Printed on recycled paper Contents ■ Organization ……………………………………………… 1 RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology ■ Message from the ……………… Director/Introduction 2/3 ■ 2002 Highlights …………………………………………… 4/5 Deputy Directors Core Program Shin-ichi Nishikawa Shinichi Aizawa ■ Cell Adhesion and Tissue Patterning (Masatoshi Takeichi) 8/9 ■ Stem Cell Biology (Shin-ichi Nishikawa) 10/11 Executive Advisor ■ Vertebrate Body Plan (Shinichi Aizawa) 12/13 Michio Seki ■ Morphogenetic Signaling (Shigeo Hayashi) 14/15 Director ■ Cell Asymmetry (Fumio Matsuzaki) 16/17 Masatoshi Takeichi ■ Organogenesis and Neurogenesis (Yoshiki Sasai) 18/19 Institutional Review Board ■ Evolutionary Regeneration Biology (Kiyokazu Agata) 20/21 Zentaro Kitagawa Vice-Director, International Institute for Advanced Studies Hiroko Ueno Creative Research Promoting Program Representative, Laboratory for Media and Communication -

Japanese Scientist in Research Scandal Found Dead (Update) 5 August 2014, by Mari Yamaguchi

Japanese scientist in research scandal found dead (Update) 5 August 2014, by Mari Yamaguchi Police and RIKEN said Sasai left what appeared to be suicide notes, but refused to disclose their contents. RIKEN spokesman Satoru Kagaya told a news conference that Sasai had three letters with him, each addressed to Haruko Obokata, a co-author of the research papers, as well as senior members of RIKEN and fellow researchers. Two other notes addressed to RIKEN officials were on Sasai's secretary's desk. Sasai's health had deteriorated over the past few months, and he had been receiving medical treatment. Kagaya said that Sasai started looking depressed in May, and that the two had hardly In this April 16, 2014 photo, Yoshiki Sasai, deputy chief seen each other recently. of the RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology, speaks during a press conference in Tokyo. Police said Sasai, 52, was found Tuesday, Aug. 5, 2014, at a government "He seemed exhausted. I could tell he was tired science institute RIKEN in Kobe, western Japan. Sasai even on the phone," Kagaya said, referring to one had supervised and co-authored stem-cell research of his last conversations with Sasai. papers that had to be retracted due to falsified contents. (AP Photo/Kyodo News) A senior Japanese scientist embroiled in a stem- cell research scandal has apparently committed suicide, police said Tuesday. Yoshiki Sasai, who supervised and co-authored stem-cell research papers that had to be retracted due to falsified contents, was found dead Tuesday at the government-affiliated science institute RIKEN in Kobe, in western Japan, according to Hyogo prefectural police.