Mahabharata: an Ideal Itihasa (History) of Ancient India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Applications Received During 1 to 31 January, 2020

Applications received during 1 to 31 January, 2020 The publication is a list of applications received during 1 to 31 January, 2020. The said publication may be treated as a notice to every person who claims or has any interest in the subject matter of Copyright or disputes the rights of the applicant to it under Rule 70 (9) of Copyright Rules, 2013. Objections, if any, may be made in writing to copyright office by post or e-mail within 30 days of the publication. Even after issue of this notice, if no work/documents are received within 30 days, it would be assumed that the applicant has no work / document to submit and as such, the application would be treated as abandoned, without further notice, with a liberty to apply afresh. S.No. Diary No. Date Title of Work Category Applicant 1 1/2020-CO/L 01/01/2020 TAGORE-2 Literary/ Dramatic RANGANATHA.Y.C SHRI BHRIGUSANHITA 2 10/2020-CO/L 01/01/2020 NASHTAJANMANG Literary/ Dramatic DR. GHANSHYAM CHANDRA UPADHYAY VIDHAN SHRI BHRIGUSANHITA 3 11/2020-CO/L 01/01/2020 Literary/ Dramatic DR. GHANSHYAM CHANDRA UPADHYAY STRIPHALIT PRAKARAN KNOWLEDGE 4 12/2020-CO/L 01/01/2020 MANAGEMENT MODEL Literary/ Dramatic DR.AVINASH SHIVAJI KHAIRNAR FOR THE MSME SHRI BHRIGUSANHITA 5 13/2020-CO/L 01/01/2020 PHALIT PRASANG Literary/ Dramatic DR. GHANSHYAM CHANDRA UPADHYAY DWITIYA PRABHAG SHRI BHRIGUSANHITA 6 14/2020-CO/L 01/01/2020 PHALIT PRASANG Literary/ Dramatic DR. GHANSHYAM CHANDRA UPADHYAY TRITIYA PRABHAG SHRI BHRIGUSANHITA 7 15/2020-CO/L 01/01/2020 Literary/ Dramatic DR. -

The Stotra - a Literary Form © 2017 IJSR Received: 14-05-2017 Accepted: 15-06-2017 Sailaja Kaipa

International Journal of Sanskrit Research 2017; 3(4): 77-79 International Journal of Sanskrit Research2015; 1(3):07-12 ISSN: 2394-7519 IJSR 2017; 3(4): 77-79 The stotra - A literary form © 2017 IJSR www.anantaajournal.com Received: 14-05-2017 Accepted: 15-06-2017 Sailaja Kaipa Sailaja Kaipa 1. The Glory of Sanskrit Literature Sri Venkatesvara University, Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh, India The Classical Sanskrit literature has inherited the spirit of the Vedas. Almost all the literary forms of classical period have been greatly inspired by the earlier literature existent in assuming new external forms. The epics have played a greater role of transmission by bringing down the ideal content of the Vedas and the Upanishads in the form of genealogical accounts of the rulers of both Solar and Lunar races. While the depiction of an ideal man has assumed the shape of the first poetic piece in the world (adikavya) in the name of Ramayana, the day today conflicts between the vice and virtue took the shape of the Mahabharata. The stress on moral teachings in the latter lead it to reckon as the fifth Veda (pancamaveda). The appealing technique of expression kindled the inquisitive and creative faculty of the man to give expression to their own feelings and ideas. The creator (poet) in man gave verbal expressions to abstract ideas and visible nature leading to the creation of poetry (kavya). Mammata succinctly expresses in a nutshell the effectiveness of the poetry (kavya) in the following lines- “Kavya is that which touches the in most cords of the human mind and diffuses itself into the crevices of the heart working up a lasting sense of delight. -

Bhagavad Gita

BHAGAVAD GITA The Global Dharma for the Third Millennium Chapter Ten Translations and commentaries compiled by Parama Karuna Devi Copyright © 2012 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved. Title ID: 4173075 ISBN-13: 978-1482548501 ISBN-10: 148254850X published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center phone: +91 94373 00906 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com © 2011 PAVAN Correspondence address: PAVAN House Siddha Mahavira patana, Puri 752002 Orissa Chapter 10: Vibhuti yoga The Yoga of powers The word vibhuti contains many meanings, such as "powers", "opulences", "glories", "magic". Every living being has some of such "magic powers" - a special ability, or strength, or beauty - but not everyone has the same powers, or a power to an absolute degree. Among the materially embodied beings, such powers are always conditioned by circumstances and exhausted when they are used. Through the correct practice of yoga, a sadhaka can develop special vibhutis up to the level of siddhi ("perfection"), usually listed as being able to become extremely small (anima siddhi), extremely large (mahima siddhi), extremely light (laghima siddhi), reconfiguring the patterns of material atoms (vasitva siddhi), materializing things by attracting atoms from other places (prapti siddhi), controlling the minds of others (isitva siddhi), assuming any shape or form (kamavasayita siddhi), and manifesting all kinds of wonders (prakamya siddhi). Another of such powers consists in entering and controlling the body of another, living or dead (parakaya pravesa). Also, the knowledge of genuine yoga enables the serious sadhaka to control the material elements (such as fire, water, air etc), control the weather (call or dispel storms and lightning, bring or withhold rain, etc), travel in different dimensions and planets without any vehicle, call the dead back into their old body (usually temporarily), and so on. -

De La Biblioteca Vaisnava

# Titulo Autor Co-autores Edicion Idioma Carpeta Bhakti Vigyan Nityananda Book 1 Bhagavad Gita Krsna Dvaipayana Bhakti Vaibhav Puri Maharaj Trust I Adi-sastras 2 Bhagavad Gita Krsna Dvaipayana Krsna Balaram Svami Bhagavat Press I Adi-sastras 3 Bhagavad Gita Krsna Dvaipayana Bhaktivinoda Thakura Ras Bihari Lal & Sons I Adi-sastras Narayan Maharaj/Visvanatha 4 Bhagavad Gita Krsna Dvaipayana Cakravarti Gaudiya Vedanta Publications I Adi-sastras 5 Bhagavad Gita Krsna Dvaipayana Sridhar Maharaj Sri Caitanya Saraswat Math E Adi-sastras 6 Bhagavad Gita Krsna Dvaipayana Sridhar Maharaj Sri Caitanya Saraswat Math I Adi-sastras 7 Bhagavad Gita Krsna Dvaipayana Swami Tripurari Mandala Publishing I Adi-sastras Bhagavad Gita 'El Dulce Canto del 8 Infinito Absoluto' Krsna Dvaipayana Atulananda Acharya E Adi-sastras Atulananda Acharya/Paramadvaiti 9 Bhagavad Gita 'La Ciencia Suprema' Krsna Dvaipayana Maharaj Seva Editorial E Adi-sastras 10 Bhagavad Gita 'Rindete a mi' Krsna Dvaipayana Bhurijana dasa VIHE E Adi-sastras Bhagavad Gita 'Study Guide of 11 Bhagavat Gita' Krsna Dvaipayana I Adi-sastras 12 Bhagavad Gita 'Tal como es' Krsna Dvaipayana Swami Prabhupada Iskcon E Adi-sastras Bhagavad Gita Mahatmyam 'Las 13 Glorias del Bhagavat Gita' Krsna Dvaipayana E Adi-sastras 14 Bhagavat arka marici mala Bhaktivinoda Thakur Iskcon Media Library I Adi-sastras 15 Brahma Samhita Brahma Bhaktivinoda Thakur Iskcon Media Library I Adi-sastras 16 Brahma Samhita Brahma Jiva Goswami Iskcon Media Library I Adi-sastras Bhaktivinoda 17 Brahma Samhita Brahma Thakur/Bhaktisiddhanta -

Year II-Chap.3-RAMAYANA

CHAPTER THREE Rama, Sita, Lakshmana and Hanuman in RAMAYANA Year II Chapter 3-RAMAYANA THE RAMAYANA Introduction Valmiki is known as Adi Kabi, the first poet. He wrote an epic in Sanskrit, the Ramayana, which depicts the life of Rama, the hero of the story. Sage Narada narrated the story of Rama to Valmiki. Ramayana is divided into the following: o Balakanda (Book of Youth) - Boyhood of Rama, o Ayodhya Kanda (Book of Ayodhya) - Life in Ayodhya after Rama and Sita’s wedding, o Aranya Kanda (Book of Forest) – Rama’s forest life and abduction of Sita by Ravana, o Kishkindha Kanda (Book of Holy Monkey Empire) – Rama’s stay in Kishkindha after meeting Hanuman and Sugriva, o Sundara Kanda (Book of Beauty) – Hanuman’s Prank-locating Sita in Ashoka grove, and o Yuddha Kanda (Book of War) – Rama’s victory over Ravana in the war and Rama’s coronation. The period after coronation of Rama is considered in the last book - Uttara Kanda. The feature story Dasaratha was the king of Kosala, an ancient kingdom that was located in present day Uttar Pradesh. Ayodhya was its capital- located on the banks of the river Sarayu. Dasaratha was loved by one and all. His subjects were happy and his kingdom was prosperous. Even though Dasaratha had everything that he desired, he was very sad at heart; he had no children. During the same time, there lived a powerful Rakshasa (demon) king in the island of Sri Lanka (Ceylon), located just south of India. He was called Ravana. He had ten heads. -

Department of Sanskrit General

1 SREE SANKARACHARYA UNIVERSITY OF SANSKRIT, KALADY RESRUCTURED SYLLABI FOR B.A PROGRAMME IN SANSKRIT GENERAL 2015 ONWARDS Faculty of Sanskrit Literature Department of Sanskrit General 2 RESRUCTURED SYLLABI FOR B.A PROGRAMME IN SANSKRIT GENERAL 2015 ONWARDS Semester I Sl. Course Title of the course No. of Hour per No. Code Credits week 1. I.A.101.En. Common English I 4 5 2. I.A.102.En. Common English II 3 4 3. I.A.107.Sg Additional Language 4 4 I- Prose, Poetry and Drama 4. I.B.111.Sg Fundamentals of 3 4 Sanskrit Language 5. I.C.124.Sg A Survey of Classical 3 4 Sanskrit Literature 6. I.C.125.Sg Modern 3 4 Sanskrit Literature 3 Semester II Sl. Course Code Title of the course No. of Hour per No. Credits week 1. II.A.103.En. Common English III 4 5 2. II.A.104.En. Common English IV 3 4 3. II.A.108.Sg Additional Language II- 4 4 Communication Skills in Sanskrit 4. II.B.112.Sg Ancient Indian Metanarrative - 3 4 Bhāsa & Kālidāsa 5. II.C.126.Sg Methodology of Sanskrit 3 4 Learning - Tantrayukti 6. II.C.127.Sg Vṛtta and Alaṅkāra 3 4 Semester III Sl. Course Title of the course No. of Hour per No. Code Credits week 1. III.A.105.En. Common English V 4 5 2. III.A.109.Sg Additional Language III – 4 5 Perennial poetry: Kālidāsa and O.N.V.Kurup 3. III.B.113.Sg Literary appreciation: Indian 4 5 perspectives 4. -

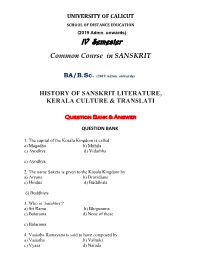

IV Semester Common Course in SANSKRIT

UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION (2019 Admn. onwards) IV Semester Common Course in SANSKRIT BA/B.Sc. (2019 Admn. onwards) HISTORY OF SANSKRIT LITERATURE, KERALA CULTURE & TRANSLATI Question Bank & Answer QUESTION BANK 1. The capital of the Kosala Kingdom is called a) Magadha b) Mithila c) Ayodhya d) Vidarbha c) Ayodhya 2. The name Saketa is given to the Kosala Kingdom by a) Aryans b) Dravidians c) Hindus d) Buddhists d) Buddhists 3. Who is ‘halabhrt’? a) Sri Rama b) Bhrgurama c) Balarama d) None of these c) Balarama 4. Vasistha Ramayana is said to have composed by a) Vasistha b) Valmiki c) Vyasa d) Narada School of Distance Education b) Valmiki 5. Adhyatma Ramayana is an extract from a) Visnu Purana b) Brahmanda Purana c) Agni Purana d) Matsya Purana . b) Brahmandapurana 6. Mula Ramayana describes the importance of a) Rama b) Sita c) Ravana d) Hanuman . d) Hanuman 7. The most well known commentary on the Ramayana is a) Valmiki Ramayana b) Bhusanam c) Dharmakuta d) Ramayananvayi b) Bhusanam 8. Ramayanadipika is written by a) Maheswaratirtha b) Vidyanatha Diksita c) Hari Pandita d) Nagesa b) Vidyanatha Dikshita 9. Valmikihrdayam is a commentary on the Ramayana written by a) Ahobala b) Govindaraja . a) Ahobala 10. ………….. is a splendid critique on the Ramayana. a) Dharmakutam b) Ramayanabhusanam c) Tirthiyam d) None of these . a) Dharmakutam 11. The author of Dharmakutam is a) Tryambaka Makhin b) Gangadhara c) Nrsimha d) Venkatacarya . a) Tryambaka Makhin History of Sanskrit Literature, Kerala Culture & Translation Page 2 School of Distance Education 12. How many verses are there in the Ramayana? a) 24,000 b) 25,000 c) 1, 00,000 d) 22,000 . -

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL of RESEARCH INSTINCT Special

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH INSTINCT SRIMAD ANDAVAN ARTS & SCIENCE COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) IN COLLABORATION WITH COMPARATIVE LITERATURE ASSOCIATION OF INDIA Special Issue: April 2015 Report of the Conference The International Conference on New Perspectives on Comparative Literature and Translation Studies in collaboration with Comparative Literature Association of India was inaugurated by Dr. Dorothy Fegueira, Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature, University of Georgia, Athens, USA, on 07.03.2015 in Srimad Andavan Arts & Science College, Tiruchirappalli 05. Dr. J. Radhika, the Principal of the college welcomed the gathering. The meeting was presided over by Mr. N.Kasturirangan, the secretary of the college who was also the patron of the conference. Dr. S. Ramamurthy, Dean of Academics and Director of the conference introduced the theme of the conference and said that the conference seeks to take stock of the pedagogical developments in Comparative Literature all over the world in order to map the Indian context in terms of the same. He added that the conference proposes to discuss the state of Comparative Literature today and will explore how the discipline has responded to the pressures of a globalised educational matrix. Dr. Dorothy Fegueira in her keynote address referred to some theoretical and ethical concerns in the study of Comparative Literature and inaugurated the conference. Dr. Chandra Mohan, General Secretary, Comparative Literature Association of India & Former Vice-President International Comparative Literature Association, presided over the plenary session of the first day and traced the activities of Comparative Literature Association of India. Prof. Seighild Bogumil, Eminent Professor in French and German Comparative Literature from Ruhr University at Bochum delivered her special address on the Comparative Literature Scenarios in Europe with reference to France and Germany. -

Introduction

Cracow lndological Studies vol. XV (2013) 10.12797/CIS. 15. 2013. 15. 01 Introduction The present volume of Cracow lndological Studies contains arti cles addressing different issues pertaining to a broadly formulated sub ject History and Society as Described in Indian Literature and Art. Its first part (Cracow lndological Studies, vol. 14) was devoted to visu al and performing arts, as obviously the interpretation of sculptures, paintings, objects of craft as well as film art cannot be neglected while searching for pieces of information providing a better insight into the ancient and modem history of India. The articles presented in the second part use literary sources in order to examine diverse aspects of the past and present. Similarly to the first part, which con tains in its subtitle the Sanskrit word drsya—‘what should be looked at’—and in this way brings together the varied phenomena which can be described by this term, starting from ancient Indian theatrical art and finishing with modem Indian cinematography, the present volume’s subtitle also refers to the indigenous Indian theory of literature, using the Sanskrit word srdvya or ‘what should be listened to’, ‘what is worth listening to’. This term covers both poetry and prose compositions. The authors of this particular volume bring manifold literary works, among them also scientific treatises and scriptures, which ‘should be listened to’ to readers’ attention and analyse them in order to have viii Lidia Sudyka, Anna Nitecka a better understanding of Indian society and culture. The essentially plural identity of Indian literature is represented in this volume by the pan-Indian Sanskrit literary tradition, Hindi literary culture encom passing the North of India and the most important and ancient among the South Indian Dravidic literatures, namely Tamil writings. -

Updated Oriental Lang 1 .Docx

Effective from the academic year 2012-2013 SANSKRIT I Semester Sanskrit - I paper (Poetry and History of Kavya Literature) Code No. LS 1082 Category – RL No.of credits: 03 No.of hrs. 06 per week Objectives Ø To develop the skill of Language acquisition. Ø To enhance writing skill and skill on analyzing the poetic concepts of ancient and modern literature. Ø To make aware of the moral values of ancient Indian literature. Ø To inculcate historical knowledge on our ancient kavya literature and culture of India. Ø To provide basic knowledge on the origin and development of Kavya Literature Course Content (Text Books) Ancient Poetry (i) kumarasambhava Mahakavya Canto-I slokas Nos 1 to 17 By Mahakavi Kalidasa (ii) “ Kim Karaniyam Kimakaraniyam ” _ Viduraniti –Slokas 1to 18 . (Taken from Mahabharatha by Vyasa) Modern poetry (iii) Kristhubhagavatam Mahakavya – Bhagavato yasoravatarah Canto VII Slokas 1 to 13 By Prof. P.C.Devassia (iv) Mahakavyas –Origin and development (Taken from A Short History of Sanskrit Literature By T.K.Ramachandra Aiyar) -2- Unit – 1 1.1 Introduction on epics 1.2 Introduction on Kalidasa 1.3 Kumarasambhava Slokas 1to 10 Unit – 2 2.1 Kumarasambhava Slokas 11to 17 2.2 Kim karaniyam Kimakaraniyam Slokas 1to 18 Unit – 3 3.1 Introduction on modern poetry 3.2 Contribution of Prof.P.C.Devassia 3.3 Christubhagavatam Slokas 1 to 13 Unit – 4 4.1 Introduction on Pre-kalidasa period 4.2 Kalidasa and his works Unit – 5 5.1 Asvaghosa, Bharavi and Magha 5.2 Vasudeva,Kshemendra and Sriharsha Books for Reference 1.Kalidasa,Kumarasambhava Mahakavya , R.S.Vadhyar&Sons, Palghat,2002 2. -

A History of Telugu Literature;

Jf THE HERITAGE OF INDIA SERIES Planned by J. N. FARQUHAR, M.A., D.Litt. (Oxon.), D.D. (Aberdeen). /The Right Reverend V. S. AZARIAH, LL.D of Dornakal. Joint (Cantab.), Bishop E. C. M.A. Editors DEWICK, (Cantab.) J. N. C. GANGULY, M.A., (Birmingham), Darsan-Sastri. Already published. The Heart of Buddhism. K. J. SAUNDERS, M.A., D.Litt. (Cantab.) A History of Kanarese Literature, 2nd ed. E. P. RICE, B.A. The Sarhkhya System, 2nd ed. A. BERRIEDALE KEITH, D.C.L., D.Litt. (Oxon.) ASoka, 2nd ed. JAMES M. MACPHAIL, M.A., M.D. Indian Painting. _2nd ed. Principal PERCY BROWN, Calcutta. Psalms of Maratha Saints. NICOL MACNICOL, M.A., D.Litt. A History of Hindi Literature. F. E, KEAY, M.A., D.Litt. The Karma-MImamsa. A. BERRIEDALE KEITH, D.C.L., D.Litt.(Oxon.) Hymns of the Tamil Saivite Saints. F. KINGSBURY, B.A., and G. E. PHILLIPS, M.A. Rabindranath Tagore. EDWARD THOMPSON, M.A. (Oxon.), Ph.D. Hymns from the Rigveda. A. A. MACDONELL, M.A., Ph.D., Hon. LL.D. Gautama Buddha. K. J. SAUNDERS, M.A., D.Litt. (Cantab.) The Coins of India. C. J. BROWN, M.A. Indian Poems by Women. ^ MRS. MACNICOL. Bengali Religious Lyrics, Sakta. EDWARD THOMPSON, M.A. (Oxon.), Ph.D., and A. M. SPENCER. Classical Sanskrit Literature, 2nd ed. A. BERRIEDALE KEITH, D.C.L., D.Litt. (Oxon.) The Music of India. H. A. POPLEY, B.A. Subjects proposed and volumes under preparation. HISTORY AND THE HERITAGE. The Early Period. The Gupta Period. The Mogul Period. -

The First English Translation of Mahabharata: Authorship, Authority, Translation and Utility Matters

Research Articles The First English Translation of Mahabharata: Authorship, Authority, Translation and Utility Matters Nandini Bhattacharya* “As Professor Max Mueller noted ‘printing is now the only from its immediate past and being congealed into a means of saving your Sanskrit literature from inevitable standard text/edition. This also meant The Mahabharata destruction’.” being textualized with auteurs that were now claiming P.C. Roy: “Preface” The Mahabharata of ‘authority’ of their ‘translation’ into modern Sanskrit; or/ Krishna Dwaipayana Vyasa: p. 30 and into the modern Indic and European vernaculars. Such translations now also clearly state the original This essay explores the issues associated with the authorship of The Mahabharata (following the inexorable fraught entry of The Mahabharata into the domain of logic of print modernity) as belonging to a person called print modernity in India. It focuses on the twin issues ‘Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa.’ of authority-authorization and utility-realism as they These vast transnational processes of The Mahabharata inform and colour such entries. I describe The Mahabharata entering within print modernity cultures also meant in India, before the 18th century, as a vast, complex and ‘fixing’ the ‘event’ genealogically, that is, within intermedially worked-out ‘event’ rather than a ‘text’ in the non-permeable generic categories. While one set of modern sense of the term. The critical distinction made individuals (Indologists such as Albrecht Weber and between a ‘work’ as self-contained and ‘text’ as porous, Friedrich Max Mueller) described The Mahabharata as enabling reader-response, must take into account that mahakavya and mahakavya as signifying ‘epic poetry,’ both (‘work’ and ‘text’) operate within, and are produced another set (Sanskritists, such as Pundit Shashadhar by the overarching operations of print modernity.