Sanskrit Literature by V Raghavan 1959 From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sahitya Akademi Translation Prize 2013

DELHI SAHITYA AKADEMI TRANSLATION PRIZE 2013 August 22, 2014, Guwahati Translation is one area that has been by and large neglected hitherto by the literary community world over and it is time others too emulate the work of the Akademi in this regard and promote translations. For, translations in addition to their role of carrying creative literature beyond known boundaries also act as rebirth of the original creative writings. Also translation, especially of ahitya Akademi’s Translation Prizes for 2013 were poems, supply to other literary traditions crafts, tools presented at a grand ceremony held at Pragyajyoti and rhythms hitherto unknown to them. He cited several SAuditorium, ITA Centre for Performing Arts, examples from Hindi poetry and their transportation Guwahati on August 22, 2014. Sahitya Akademi and into English. Jnanpith Award winner Dr Kedarnath Singh graced the occasion as a Chief Guest and Dr Vishwanath Prasad Sahitya Akademi and Jnanpith Award winner, Dr Tiwari, President, Sahitya Akademi presided over and Kedarnath Singh, in his address, spoke at length about distributed the prizes and cheques to the award winning the role and place of translations in any given literature. translators. He was very happy that the Akademi is recognizing Dr K. Sreenivasarao welcomed the Chief Guest, and celebrating the translators and translations and participants, award winning translators and other also financial incentives are available now a days to the literary connoisseurs who attended the ceremony. He translators. He also enumerated how the translations spoke at length about various efforts and programmes widened the horizons his own life and enriched his of the Akademi to promote literature through India and literary career. -

Present Day Indian Fiction in English Interpretation

Malaya Journal of Matematik, Vol. S, No. 2, 3705-3707, 2020 https://doi.org/10.26637/MJM0S20/0961 Present day Indian fiction in English interpretation S. Mangayarkarasi1 and A. Annie Christy2 Abstract The seed of Indian Writing in English was planted during the time of the British standard in India. Presently the seed has bloomed into an evergreen tree, fragrant blossoms, and ready organic products. The natural products are being tested by the local individuals, yet they are additionally being ’bit and processed’ by the outsiders. It happened simply after the steady mindful, pruning, and taking care of. Nursery workers resemble Tagore, Sri Aurobindo, R.K.Narayan, Raja Rao – to give some examples, took care of the delicate plant night and day. In the present day time, it is protected by various scholars who are getting grants and honors everywhere throughout the world. Keywords Aurobindo, fragrant blossoms, culture, convention, social qualities. 1,2Department English, Bharath Institute for Higher Education and Research, Selaiyur, Chennai-600073, Tamil Nadu, India. Article History: Received 01 October 2020; Accepted 10 December 2020 c 2020 MJM. Contents English fiction has been attempting to offer articulation to the Indian experience of the advanced difficulties. There are pun- 1 Introduction......................................3705 dits and analysts in England and America who acknowledge 2 Interpretation in Telugu literature. .3705 Indian English books. Prof. M. K. Naik comments ”one of the most prominent endowments of English instruction to India 3 Interpretation in Kannada literature . 3706 is writing fiction for, however, India was likely a wellspring 4 Interpretation in Tamil literature . 3706 head of narrating, the novel as we probably are aware today 5 Interpretation in Malayalam literature . -

Aesthetics, Subjectivity, and Classical Sanskrit Women Poets

Voices from the Margins: Aesthetics, Subjectivity, and Classical Sanskrit Women Poets by Kathryn Marie Sloane Geddes B.A., The University of British Columbia, 2016 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2018 © Kathryn Marie Sloane Geddes 2018 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, a thesis/dissertation entitled: Voices from the Margins: Aesthetics, Subjectivity, and Classical Sanskrit Women Poets submitted by Kathryn Marie Sloane Geddes in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Asian Studies Examining Committee: Adheesh Sathaye, Asian Studies Supervisor Thomas Hunter, Asian Studies Supervisory Committee Member Anne Murphy, Asian Studies Supervisory Committee Member Additional Examiner ii Abstract In this thesis, I discuss classical Sanskrit women poets and propose an alternative reading of two specific women’s works as a way to complicate current readings of Classical Sanskrit women’s poetry. I begin by situating my work in current scholarship on Classical Sanskrit women poets which discusses women’s works collectively and sees women’s work as writing with alternative literary aesthetics. Through a close reading of two women poets (c. 400 CE-900 CE) who are often linked, I will show how these women were both writing for a courtly, educated audience and argue that they have different authorial voices. In my analysis, I pay close attention to subjectivity and style, employing the frameworks of Sanskrit aesthetic theory and Classical Sanskrit literary conventions in my close readings. -

Common Perspectives in Post-Colonial Indian and African Fiction in English

COMMON PERSPECTIVES IN POST-COLONIAL INDIAN AND AFRICAN FICTION IN ENGLISH ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Bottor of IN ENGLISH LITERATURE BY AMINA KISHORE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH ALIGARH MUSLIIVI UNIVERSITY ALIGARH 1995 Abstract The introduction of the special paper on Commonwealth Literature at the Post Graduate level and the paper called 'Novel other than British and American' at the Under Graduate level at AMU were the two major eventualities which led to this study. In the paper offered to the M A students, the grouping together of Literatures from atleast four of the Commonwealth nations into one paper was basically a makeshift arrangement. The objectives behind the formulation of such separate area as courses for special study remained vaguely described and therefore unjustified. The teacher and students, were both uncertain as to why and how to hold the disparate units together. The study emerges out of such immediate dilemma and it hopes to clarify certain problematic concerns related to the student of the Commonwealth Literature. Most Commonwealth criticism follows either (a) a justificatory approach; or (b) a confrontationist approach; In approach (a) usually a defensive stand is taken by local critics and a supportive non-critical, indulgent stand is adopted by the Western critic. In both cases, the issue of language use, nomenclature and the event cycle of colonial history are the routes by which the argument is moved. Approach (b) invariably adopts the Post-Colonial Discourse as its norm of presenting the argument. According to this approach, the commonness of Commonwealth Literatures emerges from the fact that all these Literatures have walked ••• through the fires of enslavement and therefore are anguished, embattled units of creative expression. -

Portrayal of Family Ties in Ancient Sanskrit Plays: a Study

Volume II, Issue VIII, December 2014 - ISSN 2321-7065 Portrayal of Family Ties in Ancient Sanskrit Plays: A Study Dr. C. S. Srinivas Assistant Professor of English Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Technology Hyderabad India Abstract The journey of the Indian dramatic art begins with classical Sanskrit drama. The works of the ancient dramatists Bhasa, Kalidasa, Bhavabhuti and others are the products of a vigorous creative energy as well as sustained technical excellence. Ancient Sanskrit dramatists addressed several issues in their plays relating to individual, family and society. All of them shared a common interest— familial and social stability for the collective good. Thus, family and society became their most favoured sites for weaving plots for their plays. Ancient Sanskrit dramatists with their constructive idealism always portrayed harmonious filial relationships in their plays by persistently picking stories from the two great epics Ramayana and Mahabharata and puranas. The paper examines a few well-known ancient Sanskrit plays and focuses on ancient Indian family life and also those essential human values which were thought necessary and instrumental in fostering harmonious filial relationships. Keywords: Family, Filial, Harmonious, Mahabharata, Ramayana, Sanskrit drama. _______________________________________________________________________ http://www.ijellh.com 224 Volume II, Issue VIII, December 2014 - ISSN 2321-7065 The ideals of fatherhood and motherhood are cherished in Indian society since the dawn of human civilization. In Indian culture, the terms ‘father’ and ‘mother’ do not have a limited sense. ‘Father’ does not only mean the ‘male parent’ or the man who is the cause of one’s birth. In a broader sense, ‘father’ means any ‘elderly venerable man’. -

Sanskrit Literature and the Scientific Development in India

SANSKRIT LITERATURE AND THE SCIENTIFIC DEVELOPMENT IN INDIA By : Justice Markandey Katju, Judge, Supreme Court of India Speech delivered on 27.11.2010 at Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi Friends, It is an honour for me to be invited to speak in this great University which has produced eminent scholars, many of them of world repute. It is also an honour for me to be invited to Varanasi, a city which has been a great seat of Indian culture for thousands of years. The topic which I have chosen to speak on today is : ‘Sanskrit Literature and the Scientific Development in India’. I have chosen this topic because this is the age of science, and to progress we must spread the scientific outlook among our masses. Today India is facing huge problems, social, economic and cultural. In my opinion these can only be solved by science. We have to spread the scientific outlook to every nook and corner of our country. And by science I mean not just physics, chemistry and biology but the entire scientific outlook. We must transform our people and make them modern minded. By modern I do not mean wearing a fine suit or tie or a pretty skirt or jeans. A person can be wearing that and yet be backward mentally. By being modern I mean having a modern mind, which means a logical mind, a questioning mind, a scientific mind. The foundation of Indian culture is based on the Sanskrit language. There is a misconception about the Sanskrit language that it is only a language for chanting mantras in temples or religious ceremonies. -

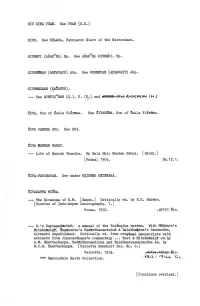

P. ) AV Gereaw (M.) Hitherto Unpublished. Critically Ed. From

SIU KING YUAN. See YUAN (S.K.) SIUD. See SULACA, Patriarch Elect of the Nestorians. SIUNECI (ARAKcEL) Bp. See ARAKcEL SIUNECI, Bp. SIURMEEAN (ARTAVAZD) Abp. See SURMEYAN (ARDAVAZT) Abp. SIURMELEAN (KOATUR). - -- See AVETIKcEAN (G.), S. (K.) and AUCIILR {P. ) AV GEREAw (M.) SIVA, Son of Sukla Visrama. See SIVARAMA, Son of Sukla Visrama. SIVA CANDRA GUI. See GUI. SIVA NANDAN SAHAY. - -- Life of Harish Chandra. By Balm Shio Nandan Sahai. [Hindi.] [Patna] 1905. Br.12.1. SIVA- PARINAYAH. See under KRISHNA RAJANAKA. SIVADATTA MISRA. - -- The Sivakosa of S.M. [Sansk.] Critically ed. by R.G. Harshe. [Sources of Indo -Aryan Lexicography, 7.] Poona, 1952. .49123 Siv. - -- S.'s Saptapadartht; a manual of the Vaisesika system. With Madhava's Mitabhasint, Sesananta's Padarthacandrika & Balabhaadra's Sandarbha, hitherto unpublished. Critically ed. from original manuscripts with extracts from Jinavardhana's commentary ... Text & Mitabhasint ed.by A.M. Bhattacharya, Padarthacandrika and Balabhadrasandarbha ed. by N.C.B. Bhattacharya. [Calcutta Sanskrit Ser. No. 8.] Calcutta, 1934. .6912+.1-4143 giv. * ** Berriedale Keith Collection. [Continued overleaf.] ADDITIONS SIU (BOBBY). - -- Women of China; imperialism and women's resistance, 1900 -1949. Lond., 1982. .3961(5103 -04) Siu. SIVACHEV (NIKOLAY V.). - -- and YAKOVLEV (NIKOLAY N.). - -- Russia and the United States. Tr. by O.A. Titelbaum. [The U.S. in the World: Foreign Perspectives.] Chicago, 1980. .327(73 :47) Siv. gIVADITYA MARA [continued]. - -- Saptapadartht. Ed. with introd., translation and notes by D. Gurumurti. With a foreword by Sir S. Radhakrishnan. [Devanagari and Eng.] Madras, 1932. .8712:.18143 LN: 1 S / /,/t *** Berriedale Keith Collection. 8q12: SIVADJIAN (J.). - -- Les fièvres et les médicaments antithermiques. -

C 61200 (Pages : 2)� Name � Reg

C 61200 (Pages : 2) Name Reg. No FOURTH SEMESTER B.A./B.Sc. DEGREE EXAMINATION APRIL 2019 (CUCBCSS—UG) Sanskrit SKT 4A 10—HISTORY OF SANSKRIT LITERATURE, KERALA CULTURE AND TRANSLATION Time ; Three Hours Maximum : 80 Marks Answers may be written either in Sanskrit or in English or in Malayalam. In writing Sanskrit, Devanagari script should be used. I. Answer any ten in one or two words : 1 Who is known as Adikavi ? 2 What does the term "Panivada" indicate ? 3 Who is the author of Raghunathanbhyudaya ? 4 Which temple art form is enacted only by women ? Fill in the blanks with suitable words : 5 is the longest poem ever known in literary history. 6 There are kandas in Ramayana. 7 Narayanabhatta represented school of Mimamsa. 8 Kutiyattam is performed at specially built Temple theatres known as Answer in one word : 9 Which text is composed by Manaveda for Krishnanattam ? .10 Who is the author of Darsanamala ? 11 Name the historical poem written by A.R. Rajaraja Varma ? 12 Mention the art form in which humour is of much importance ? (10 x 1 = 10 marks) II. Write short notes on any five of the following : 13 Valmiki. 14 Rajatarangini. 15 Bharatachampu. 16 Sree Narayana Guru. 17 Yasastilaka Champu. 18 Punnasseri Nambi. 19 Chakyarkuttu. (5 x 4 = 20 marks) Turn over 2 C 61200 III. Write short essays on any six of the following : 20 Date of Ramayana. 21 Content of Narayaneeya. 22 18 Parvas of Mahabharata. 23 Peculiarities of Champukavyas. 24 Musical instruments in Kutiyattam. 25 Works of Sankaracharya. 26 Difference between Chakyarkuttu and Nangiarkuttu. -

Applications Received During 1 to 31 January, 2020

Applications received during 1 to 31 January, 2020 The publication is a list of applications received during 1 to 31 January, 2020. The said publication may be treated as a notice to every person who claims or has any interest in the subject matter of Copyright or disputes the rights of the applicant to it under Rule 70 (9) of Copyright Rules, 2013. Objections, if any, may be made in writing to copyright office by post or e-mail within 30 days of the publication. Even after issue of this notice, if no work/documents are received within 30 days, it would be assumed that the applicant has no work / document to submit and as such, the application would be treated as abandoned, without further notice, with a liberty to apply afresh. S.No. Diary No. Date Title of Work Category Applicant 1 1/2020-CO/L 01/01/2020 TAGORE-2 Literary/ Dramatic RANGANATHA.Y.C SHRI BHRIGUSANHITA 2 10/2020-CO/L 01/01/2020 NASHTAJANMANG Literary/ Dramatic DR. GHANSHYAM CHANDRA UPADHYAY VIDHAN SHRI BHRIGUSANHITA 3 11/2020-CO/L 01/01/2020 Literary/ Dramatic DR. GHANSHYAM CHANDRA UPADHYAY STRIPHALIT PRAKARAN KNOWLEDGE 4 12/2020-CO/L 01/01/2020 MANAGEMENT MODEL Literary/ Dramatic DR.AVINASH SHIVAJI KHAIRNAR FOR THE MSME SHRI BHRIGUSANHITA 5 13/2020-CO/L 01/01/2020 PHALIT PRASANG Literary/ Dramatic DR. GHANSHYAM CHANDRA UPADHYAY DWITIYA PRABHAG SHRI BHRIGUSANHITA 6 14/2020-CO/L 01/01/2020 PHALIT PRASANG Literary/ Dramatic DR. GHANSHYAM CHANDRA UPADHYAY TRITIYA PRABHAG SHRI BHRIGUSANHITA 7 15/2020-CO/L 01/01/2020 Literary/ Dramatic DR. -

Prabuddha Bharata

2 THE ROAD TO WISDOM Swami Vivekananda on The Mechanics of Prana ll the automatic movements and all the Aconscious movements are the working of Prana through the nerves. It will be a very good thing to have control over the unconscious actions. Man is an infinite circle whose circumference is nowhere, but the centre is located in one spot; and God is an infinite circle whose circumference is nowhere, but whose centre is everywhere. man could refrain from doing evil. All the He works through all hands, sees through systems of ethics teach, ‘Do not steal!’ Very all eyes, walks on all feet, breathes through good; but why does a man steal? Because all all bodies, lives in all life, speaks through stealing, robbing, and other evil actions, as a every mouth, and thinks through every rule, have become automatic. The systematic brain. Man can become like God and robber, thief, liar, unjust man and woman, acquire control over the whole universe if are all these in spite of themselves! It is he multiplies infinitely his centre of self- really a tremendous psychological problem. consciousness. Consciousness, therefore, is We should look upon man in the most the chief thing to understand. Let us say charitable light. It is not easy to be good. that here is an infinite line amid darkness. What are you but mere machines until We do not see the line, but on it there is one you are free? Should you be proud because luminous point which moves on. As it moves you are good? Certainly not. -

The Dasarupa a Treatise on Hindu Dramaturgy Columbia University Indo-Iranian Series

<K.X-."»3« .*:j«."3t...fc". wl ^^*je*w £gf SANfiNlRETAN V1SWABHARAT1 UBRARY ftlO 72, T? Siali • <••«.•• THE DASARUPA A TREATISE ON HINDU DRAMATURGY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY INDO-IRANIAN SERIES EDITED R Y A. V. WILLIAMS JACKSON FaOFCSSOR OF INOO-IRANIAH LANGUAGES IN COLUMBIA UNtVERSITY Volume 7 Neto York COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS 1912 AU righis reserved THE DASARUPA A TREATISE ON HINDU DRAMATURGY By DHANAMJAYA NOW FIRST TRANSLATED KROM THE SANSKRIT WITH THE TEXT AND AN INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY GEORGE C. O. HAAS, A.M., Ph.D. SOMKT1MB PBLLOW IN INDO-IftANIAN LANCOAGES JN COLUMBIA UNIVBRSITY Nrto Yor* COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS 1912 Alt rights reserved 2 Copyright 191 By Columbia University Press Printed from type. Auffiut, 1913 r«t*« ©r tMC MtV EKA PHtMTI«« COHM«r tAMCUTM. I»».. TO MY FATHER PREFATORY NOTE In the present volume an important treatise on the canons of dramatic composition in early India is published for the first time in an English translation, with the text, explanatory notes, and an introductory account of the author and his work. As a con- tribution to our knowledge of Hindu dramaturgy, I am glad to accord the book a place in the Indo-Iranian Series, particularly as it comes from one who has long been associated with me as a co-worker in the Oriental field. A. V. Williams Jackson. V» PREFACE The publication of the present volume, originally planned for 1909, has been delayed until now by ^arious contingencies both unforeseen and unavoidable. While in some respects unfortu- nate, this delay has been of advantagc in giving me opportunities for further investigation and enabling me to add considerably to my collection of comparative material. -

The Journal Ie Music Academy

THE JOURNAL OF IE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS A QUARTERLY OTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MUSIC XIII 1962 Parts I-£V _ j 5tt i TOTftr 1 ®r?r <nr firerftr ii dwell not in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins, - the Sun; where my Bhaktas sing, there be I, ! ” EDITED BY V. RAGHAVAN, M.A., PH.D. 1 9 6 2 PUBLISHED BY HE MUSIC ACADEMY, MADRAS 115-E, M OW BRAY’S RO AD, M ADRAS-14. "iption—Inland Rs, 4. Foreign 8 sh. Post paid. i ADVERTISEMENT CHARGES I S COVER PAGES: if Back (outside) $ if Front (inside) i Back (D o.) if 0 if INSIDE PAGES: if 1st page (after cover) if if Ot^er pages (each) 1 £M E N i if k reference will be given to advertisers of if instruments and books and other artistic wares. if I Special position and special rate on application. Xif Xtx XK XK X&< i - XK... >&< >*< >*<. tG O^ & O +O +f >*< >•< >*« X NOTICE All correspondence should be addressed to Dr. V. R Editor, Journal of the Music Academy, Madras-14. Articles on subjects of music and dance are accep publication on the understanding that they are contribute) to the Journal of tlie Music Academy. All manuscripts should be legibly written or preferab written (double spaced—on one side of the paper only) and be signed by the writer (giving his address in full). The Editor of the Journal is not responsible for t1 expressed by individual contributors. All books, advertisement, moneys and cheque ♦ended for the Journal should be sent to D CONTENTS 'le X X X V th Madras Music Conference, 1961 : Official Report Alapa and Rasa-Bhava id wan C.