Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keenan Allen, Mike Williams and Austin Ekeler, and Will Also Have Newly-Signed 6 Sun ., Oct

GAME RELEASE PRESEASON WEEK 2 vs. SAN FRANCISCO 49ERS SUN. AUG. 22, 2021 | 4:30 PM PT bolts build under brandon staley 20212020 chargers schedule The Los Angeles Chargers take on the San Francisco 49ers for the 49th time ever PRESEASON (1-0) in the preseason, kicking off at 4:30 p m. PT from SoFi Stadium . Spero Dedes, Dan Wk Date Opponent TV Time*/Res. Fouts and LaDainian Tomlinson have the call on KCBS while Matt “Money” Smith, 1 Sat ., Aug . 14 at L .A . Rams KCBS W, 13-6 Daniel Jeremiah and Shannon Farren will broadcast on the Chargers Radio Network 2 Sun ., Aug . 22 SAN FRANCISCO KCBS 4:30 p .m . airwaves on ALT FM-98 7. Adrian Garcia-Marquez and Francisco Pinto will present the game in Spanish simulcast on Estrella TV and Que Buena FM 105 .5/94 .3 . 3 Sat ., Aug . 28 at Seattle KCBS 7:00 p .m . REGULAR SEASON (0-0) The Bolts unveiled a new logo and uniforms in early 2020, and now will be unveiling a revamped team under new head coach, Brandon Staley . Staley, who served as the Wk Date Opponent TV Time*/Res. defensive coordinator for the Rams in 2020, will begin his first year as a head coach 1 Sun ., Sept . 12 at Washington CBS 10:00 a .m . by playing against his former team in the first game of the preseason . 2 Sun ., Sept . 19 DALLAS CBS 1:25 p .m . 3 Sun ., Sept . 26 at Kansas City CBS 10:00 a .m . Reigning Offensive Rookie of the YearJustin Herbert looks to build off his 2020 season, 4 Mon ., Oct . -

Our School Preschool Songbook

September Songs WELCOME THE TALL TREES Sung to: “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” Sung to: “Frère Jacques” Welcome, welcome, everyone, Tall trees standing, tall trees standing, Now you’re here, we’ll have some fun. On the hill, on the hill, First we’ll clap our hands just so, See them all together, see them all together, Then we’ll bend and touch our toe. So very still. So very still. Welcome, welcome, everyone, Wind is blowing, wind is blowing, Now you’re here, we’ll have some fun. On the trees, on the trees, See them swaying gently, see them swaying OLD GLORY gently, Sung to: “Oh, My Darling Clementine” In the breeze. In the breeze. On a flag pole, in our city, Waves a flag, a sight to see. Sun is shining, sun is shining, Colored red and white and blue, On the leaves, on the trees, It flies for me and you. Now they all are warmer, and they all are smiling, In the breeze. In the breeze. Old Glory! Old Glory! We will keep it waving free. PRESCHOOL HERE WE ARE It’s a symbol of our nation. Sung to: “Oh, My Darling” And it flies for you and me. Oh, we're ready, Oh, we're ready, to start Preschool. SEVEN DAYS A WEEK We'll learn many things Sung to: “For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow” and have lots of fun too. Oh, there’s 7 days in a week, 7 days in a week, So we're ready, so we're ready, Seven days in a week, and I can say them all. -

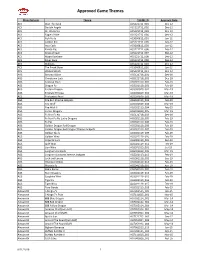

Approved Game Themes

Approved Game Themes Manufacturer Theme THEME ID Approval Date ACS Bust The Bank ACS121712_001 Dec-12 ACS Double Angels ACS121712_002 Dec-12 ACS Dr. Watts Up ACS121712_003 Dec-12 ACS Eagle's Pride ACS121712_004 Dec-12 ACS Fish Party ACS060812_001 Jun-12 ACS Golden Koi ACS121712_005 Dec-12 ACS Inca Cash ACS060812_003 Jun-12 ACS Karate Pig ACS121712_006 Dec-12 ACS Kings of Cash ACS121712_007 Dec-12 ACS Magic Rainbow ACS121712_008 Dec-12 ACS Silver Fang ACS121712_009 Dec-12 ACS Stallions ACS121712_010 Dec-12 ACS The Freak Show ACS060812_002 Jun-12 ACS Wicked Witch ACS121712_011 Dec-12 AGS Bonanza Blast AGS121718_001 Dec-18 AGS Chinatown Luck AGS121718_002 Dec-18 AGS Colossal Stars AGS021119_001 Feb-19 AGS Dragon Fa AGS021119_002 Feb-19 AGS Eastern Dragon AGS031819_001 Mar-19 AGS Emerald Princess AGS031819_002 Mar-19 AGS Enchanted Pearl AGS031819_003 Mar-19 AGS Fire Bull Xtreme Jackpots AGS021119_003 Feb-19 AGS Fire Wolf AGS031819_004 Mar-19 AGS Fire Wolf II AGS021119_004 Feb-19 AGS Forest Dragons AGS031819_005 Mar-19 AGS Fu Nan Fu Nu AGS121718_003 Dec-18 AGS Fu Nan Fu Nu Lucky Dragons AGS021119_005 Feb-19 AGS Fu Pig AGS021119_006 Feb-19 AGS Golden Dragon Red Dragon AGS021119_008 Feb-19 AGS Golden Dragon Red Dragon Xtreme Jackpots AGS021119_007 Feb-19 AGS Golden Skulls AGS021119_009 Feb-19 AGS Golden Wins AGS021119_010 Feb-19 AGS Imperial Luck AGS091119_001 Sep-19 AGS Jade Wins AGS021119_011 Feb-19 AGS Lion Wins AGS071019_001 Jul-19 AGS Longhorn Jackpots AGS031819_006 Mar-19 AGS Longhorn Jackpots Xtreme Jackpots AGS021119_012 Feb-19 AGS Luck -

Spectral Distortions of the Cosmic Microwave Background Dissertation

Spectral Distortions of the Cosmic Microwave Background Dissertation der Fakult¨at fur¨ Physik der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universit¨at Munc¨ hen angefertigt von Jens Chluba aus Tralee (Irland) Munc¨ hen, den 31. M¨arz 2005 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Rashid Sunyaev, MPA Garching 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Viatcheslav Mukhanov, LMU Munc¨ hen Tag der mundlic¨ hen Prufung:¨ 19. Juli 2005 Die Sterne Ich sehe oft um Mitternacht, wenn ich mein Werk getan und niemand mehr im Hause wacht, die Stern am Himmel an. Sie gehn da, hin und her, zerstreut als L¨ammer auf der Flur; in Rudeln auch, und aufgereiht wie Perlen an der Schnur; und funkeln alle weit und breit, und funkeln rein und sch¨on; ich seh die große Herrlichkeit, und kann nicht satt mich sehn... Dann saget unterm Himmelszelt mein Herz mir in der Brust; Es gibt was Bessers in der Welt als all ihr Schmerz und Lust. Matthias Claudius Contents Abstract ix 1 Introduction 1 1.1 General introduction on CMB . 1 1.2 Spectral distortions of the CMB . 5 1.2.1 The SZ effect . 5 1.2.2 Spectral distortion due to energy release in the early Universe . 8 1.3 In this Thesis . 10 2 SZ clusters of galaxies: influence of the motion of the Solar System 13 2.1 General transformation laws . 14 2.2 Transformation of the cluster signal . 16 2.3 Multi-frequency observations of clusters . 18 2.3.1 Dipolar asymmetry in the number of observed clusters . 19 2.3.2 Estimates for the dipolar asymmetry in the cluster number counts . -

George Paynter Career

Paner Family Baseball Family The Professional Baseball Life & Times of George W. Paynter (Paner) (“the ball player”) So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past - The thing that connects us is love. 1 My Grandfather, George W. Paynter (Paner), was on his own from about age 13 (1884), after his Father died at age 31. 1800s generations spelling of Paner varied, but in Germanic Cincinnati they likely sounded alike. Throughout his pro baseball playing he was Paynter. He died when I was in the 4th Grade (1950). I only knew him from our one or two visits each year to see extended family in Cincinnati. I often heard - “ So you’re the Grandson of George Paner - the ball player”. Though his single game in the Major Leagues was 50+ years earlier “the ball player” title stuck due to his zest for playing more than 20 years, in and out of town, in very competitive pro and semi-pro leagues until age 42, and rooting for the beloved home town Reds all his life. Kevin Costner’s line in Field of Dreams - "I only knew him later, after life beat him down.", spoke of my Grandfather to me. George Paynter’s baseball and life story is compelling: • Strong semi-pro years, then briefly in minors at Lynchburg VA. (April, 1894) • “Cup of coffee” career single game in the National League (August 12, 1894) • Devastating Southern League game beaning ( August, 1896) • Patient in the South’s first Hospital for the Insane in Tuscaloosa, AL (1896) • Wife’s (my Grandmother) trip to gain his release and, teach him skills again • Losing George Jr at age 11, in a gruesome homicide (1905) • Playing another 15 years of very competitive pro / semi-pro baseball and loving the game a lifetime. -

College Coaching Contracts: a Practical Perspective Martin J

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 1 Article 5 Issue 2 Spring College Coaching Contracts: A Practical Perspective Martin J. Greenberg Marquette University Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation Martin J. Greenberg, College Coaching Contracts: A Practical Perspective, 1 Marq. Sports L. J. 207 (1991) Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol1/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COLLEGE COACHING CONTRACTS: A PRACTICAL PERSPECTIVE* MARTIN J. GREENBERG I. COLLEGE COACHES CONTRACTS A. Introduction - "The Environment" When is a contract not a contract? Where is job security as fleeting as the last seconds of a basketball victory? In what field is an employment contract broken as easily as made? None other than in the world of college coaching. At the commencement of the 1988-89 college basketball season, a total of 39 schools or approximately 13.4% of the 294 Division I institu- tions had new coaches at the helm.1 This compares with an all-time high of 66 new coaches or approximately 22.8% of Division I schools during the previous season.2 During the 1980s, approximately 384 coaching changes have taken place in Division I schools.3 Approximately 53 basketball coaches have changed jobs since the end of the 1989-90 season.4 The Amer- ican Football Coaches Association indicates that head football coaches re- main in NCAA Division I-A football programs for an average of only 2.8 years.5 The number of coaches employed at the 279 schools that have played in Division I Men's Basketball for all of the past 15 seasons include: Copyright 1991 by Martin J. -

\0-9\0 and X ... \0-9\0 Grad Nord ... \0-9\0013 ... \0-9\007 Car Chase ... \0-9\1 X 1 Kampf ... \0-9\1, 2, 3

... \0-9\0 and X ... \0-9\0 Grad Nord ... \0-9\0013 ... \0-9\007 Car Chase ... \0-9\1 x 1 Kampf ... \0-9\1, 2, 3 ... \0-9\1,000,000 ... \0-9\10 Pin ... \0-9\10... Knockout! ... \0-9\100 Meter Dash ... \0-9\100 Mile Race ... \0-9\100,000 Pyramid, The ... \0-9\1000 Miglia Volume I - 1927-1933 ... \0-9\1000 Miler ... \0-9\1000 Miler v2.0 ... \0-9\1000 Miles ... \0-9\10000 Meters ... \0-9\10-Pin Bowling ... \0-9\10th Frame_001 ... \0-9\10th Frame_002 ... \0-9\1-3-5-7 ... \0-9\14-15 Puzzle, The ... \0-9\15 Pietnastka ... \0-9\15 Solitaire ... \0-9\15-Puzzle, The ... \0-9\17 und 04 ... \0-9\17 und 4 ... \0-9\17+4_001 ... \0-9\17+4_002 ... \0-9\17+4_003 ... \0-9\17+4_004 ... \0-9\1789 ... \0-9\18 Uhren ... \0-9\180 ... \0-9\19 Part One - Boot Camp ... \0-9\1942_001 ... \0-9\1942_002 ... \0-9\1942_003 ... \0-9\1943 - One Year After ... \0-9\1943 - The Battle of Midway ... \0-9\1944 ... \0-9\1948 ... \0-9\1985 ... \0-9\1985 - The Day After ... \0-9\1991 World Cup Knockout, The ... \0-9\1994 - Ten Years After ... \0-9\1st Division Manager ... \0-9\2 Worms War ... \0-9\20 Tons ... \0-9\20.000 Meilen unter dem Meer ... \0-9\2001 ... \0-9\2010 ... \0-9\21 ... \0-9\2112 - The Battle for Planet Earth ... \0-9\221B Baker Street ... \0-9\23 Matches .. -

2019-04-24 Edition

Vote Rocky Shanehsaz For Noblesville City Council on May 7! Visionary. Collaborative. Community Focused. Learn more at RockyforCouncil.com Paid for by the Rocky For Council Campaign EDNESDAY PRIL TODAy’s WeaTHER W , A 24, 2019 Today: Partly sunny. Tonight: Partly to mostly cloudy. SHERIDAN | NOBLESVILLE | CICERO | ARCADIA Scattered showers or storms. IKE ATLANTA | WESTFIELD | CARMEL | FISHERS NEWS GATHERING L & PARTNER FOLLOW US! HIGH: 68 LOW: 54 Churches to stream services . County partners with Noblesville Prayer IMS for 500 Days of May Breakfast canceled over legal worries The REPORTER watch the service for those The Noblesville Prayer interested. Breakfast scheduled for The prayer breakfast May 2 at White River is held in conjunction with Christian Church has been the National Day of Prayer. canceled. Following the 2018 No- In lieu of the tradition- blesville Mayor’s Prayer al breakfast, many local Breakfast, the city turned churches have offered to the event organization over stream a Facebook Live to Helping Hands of No- prayer service that morning. blesville after receiving out- Once the event has been side pressure and potential organized, social media litigation over separation of will be used to share de- church and state – and those tails of when and where to concerns have resurfaced. Westfield launches Photo provided SafeRoads campaign Hamilton County Tourism is working with the Indianapolis Motor Speedway to connect with Hamilton County and local cities and celebrate the month of May. The IMS requests that the county fly the The REPORTER • Education: The City Indianapolis 500 flag during the entire month of May. On Monday, the Indy 500 flag was raised over On Tuesday, May- will implement ongo- the Courthouse. -

Licensed Gambling Operators 9-30-2020

9/30/2020 PROVIDED BY THE MONTANA DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, GAMBLING CONTROL DIVISION LICENSED GAMBLING OPERATORS and LICENSEES for FISCAL YEAR 2021 GROUPED BY COUNTY, CITY AND FINALLY BY LOCATION NAME. COUNTY: BEAVERHEAD CITY: DILLON 4040442-004-GOA 15 Licensed Machine(s) BLACKTAIL STATION 26 S MONTANA ST DILLON MT 59725 Licensee: BLACKTAIL STATION INC 4065304-003-GOA 2 Licensed Machine(s) CLUB BAR 134 N MONTANA ST DILLON MT 59725 Licensee: CLUB BAR 6429929-004-GOA 5 Licensed Machine(s) GATEWAY CANYON TRAVEL PLAZA 4055 REBICH LN DILLON MT 59725 Licensee: GATEWAY CANYON TRAVEL PLAZA INC. 6665116-003-GOA 9 Licensed Machine(s) GOLDEN BAR & CASINO 8 N MONTANA ST DILLON MT 59725 Licensee: GOLDEN BAR & CASINO, LLC 6329932-002-GOA 11 Licensed Machine(s) KLONDIKE INN 33 E BANNACK ST DILLON MT 59725 Licensee: CKI, LLC 6460969-004-GOA 5 Licensed Machine(s) KNOTTY PINE TAVERN 17 E BANNACK ST DILLON MT 59725 Licensee: B & R ENTERPRISES LLC 4091300-008-GOA 20 Licensed Machine(s) LUCKY LIL'S CASINO OF DILLON 635 N MONTANA ST DILLON MT 59725 Licensee: DILLON CASINO INC 4145194-013-GOA 20 Licensed Machine(s) MAGIC DIAMOND CASINO OF DILLON 101 E HELENA ST DILLON MT 59725 Licensee: TOWN PUMP OF HARLOWTOWN INC WEB-MT_mr011 Page 1 of 191 9/30/2020 PROVIDED BY THE MONTANA DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, GAMBLING CONTROL DIVISION LICENSED GAMBLING OPERATORS and LICENSEES for FISCAL YEAR 2021 GROUPED BY COUNTY, CITY AND FINALLY BY LOCATION NAME. COUNTY: BEAVERHEAD CITY: DILLON 6718975-003-GOA 4 Licensed Machine(s) OFFICE BAR 21 E BANNACK ST DILLON MT 59725 Licensee: ZTIK -

Karaoke Song Book Karaoke Nights Frankfurt’S #1 Karaoke

KARAOKE SONG BOOK KARAOKE NIGHTS FRANKFURT’S #1 KARAOKE SONGS BY TITLE THERE’S NO PARTY LIKE AN WAXY’S PARTY! Want to sing? Simply find a song and give it to our DJ or host! If the song isn’t in the book, just ask we may have it! We do get busy, so we may only be able to take 1 song! Sing, dance and be merry, but please take care of your belongings! Are you celebrating something? Let us know! Enjoying the party? Fancy trying out hosting or KJ (karaoke jockey)? Then speak to a member of our karaoke team. Most importantly grab a drink, be yourself and have fun! Contact [email protected] for any other information... YYOUOU AARERE THETHE GINGIN TOTO MY MY TONICTONIC A I L C S E P - S F - I S S H B I & R C - H S I P D S A - L B IRISH PUB A U - S R G E R S o'reilly's Englische Titel / English Songs 10CC 30H!3 & Ke$ha A Perfect Circle Donna Blah Blah Blah A Stranger Dreadlock Holiday My First Kiss Pet I'm Mandy 311 The Noose I'm Not In Love Beyond The Gray Sky A Tribe Called Quest Rubber Bullets 3Oh!3 & Katy Perry Can I Kick It Things We Do For Love Starstrukk A1 Wall Street Shuffle 3OH!3 & Ke$ha Caught In Middle 1910 Fruitgum Factory My First Kiss Caught In The Middle Simon Says 3T Everytime 1975 Anything Like A Rose Girls 4 Non Blondes Make It Good Robbers What's Up No More Sex.... -

Notre Dame Scholastic, Vol. 109, No. 08

SCHOLASTIC NOVEMBER 17^ 1967 AU)Abiv gYBirgirg B'0'0'o"o'oT^Tro"oT>TyrgTnnnnnn: lamptti^^hop i"o"6 0 60 0 0 oinnnnnnrB o"o"a"o"6"aoa"6"o"a"o"OTii;; Perfect for the weather that's here . i and the weather to come THE GENUINE Lonoon F06 MAINCOAT ® Weather, even Michiana weather, poses no ]Droblem for the Maincoat® with its zip-in liner of 100% Alpaca. The shell is 65% Dacron*/35% cotton for wash and wear convenience and, as an added feature, the entire coat is treated with Ze Pel* for re sistance to stains. This coat serves you long and well. In Oyster, Natural and Black. $60 *DuPont's reg. T.M. Stop m and browse . it's YOUR store! ldL9JL9.ft.9.g..9.9.9.g ft 9 9 ft I GILBERT'S 19.9.9.9.9.9,9.9 9 9.9.9.9,9,9JU>J>^ ON THE CAMPUS . NOTRE DAME yaTa'a~o"tfTro"o"o"a"a~o~gTnnTnnmnnnnnjTn n ro'o'o'o'o'oo 0 0 0 0 eiro'o~o'o'o'o'o'o'o"o'o oo o o a Ox Ifs a small price to pay . PALM BEACH 4-PIECE TRIP-L-AIRE A complete wardrobe! You enjoy a 100% Avool, natural shoulder herring bone suit, with vest, plus a pair of solid color-coordinated slacks ... by mixing and matching you have an outfit for sports, dress or leisure. Choose yours from Gray or Olive tones. $85 Trip-L-Aire engineered by Palm Beach We invite you to select and wear your apparel now . -

2006 Inductees

HALL OF HONOR The University of Houston Hall of Honor was es- 1978 2002 tablished in 1971 to recognize and honor those Tom Paciorek (BB, ‘66-68) Danny Davis (FB, ‘76-78) whose particpation and contributions enriched Homero Blancas (Golf, ‘60-62) Dwight Jones (MBB, ‘71-73) COACHING STAFF and strengthened the Athletics Department. Carol Lewis (TR, ‘82-85) 1981 Bruce Lietzke (Golf, ‘70-73) All student-athletes are required to wait five Johnny Goyen (City Councilman) Jim Nantz (Broadcasting) years after they complete their eligibility before Don Chaney (MBB, ‘65-68) Tom Tellez (TR Coach, ‘76-98) they qualify for the honor. Bill Rogers (Golf, ‘70-73) 2004 1971 1982 Billy Ray Brown (Golf, ‘82-85) Guy V. Lewis (MBB, ‘46-47) Alden Pasche (MBB Coach, ‘46-56) Ollan Cassel (TR, ‘60-61) Rex Baxter, Jr. (Golf, ‘55-57) Bo Burris (FB, ‘64-66) Carin Cone (Swimming, ‘58-60) Gene Shannon (FB, ‘49-51) Richard Crawford (Golf, ‘59-61) 1983 Lovette Hill (BB Coach, ‘50-74) 1972 Harry Fouke (AD, ‘45-79) Jolanda Jones (TR, ‘85-88) Gary Phillips (MBB, ‘58-61) Warren McVea (FB, ‘65-67) John E. Hoff (Tennis coach, ‘46-66) 1998 Ted Nance (SID, ‘56-79, 87-93) Clyde Drexler (MBB, ‘80-83) Michael Young (MBB, ‘80-84) 1973 Sue Garrison (Director of Women’s Athletics, ‘45-79) J.D. Kimmel (FB, ‘52) Flo Hyman (VB, ‘74-76) 2006 Carl Lewis (TR, ‘80-81) Dwight Davis (MBB, ‘69-72) 1974 Guy V Lewis (MBB Coach, ‘56-86) Joe DeLoach (TR, ‘87-88) Hogan Wharton (FB, ‘57-58) Hakeem Olajuwon (MBB, ‘81-84) Marty Fleckman (Golf, ‘64-66) Dick Post (FB, ‘64-66) Ken Spain (MBB, ‘66-69) Leonard Hilton (TR, ‘67-71) Elvin Hayes (MBB, ‘65-68) Wilson Whitley (FB, ‘73-76) David Hodge (FB, ‘75-79) Dave Williams (Golf Coach, ‘52-87) Dianne Johannigman (Swimming, ‘78-81) 1975 Bill Yeoman (FB Coach, ‘62-86) Margaret Redfearn (Kitchen) (Tennis, ‘82-85) Corbin J.