Copies of Mcgovern's Poems Were

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

O Klahoma City

MEDIA GUIDE O M A A H C L I K T Y O T R H U N D E 2 0 1 4 2 0 1 5 THUNDER.NBA.COM TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION ALL-TIME RECORDS General Information .....................................................................................4 Year-By-Year Record ..............................................................................116 All-Time Coaching Records .....................................................................117 THUNDER OWNERSHIP GROUP Opening Night ..........................................................................................118 Clayton I. Bennett ........................................................................................6 All-Time Opening-Night Starting Lineups ................................................119 2014-2015 OKLAHOMA CITY THUNDER SEASON SCHEDULE Board of Directors ........................................................................................7 High-Low Scoring Games/Win-Loss Streaks ..........................................120 All-Time Winning-Losing Streaks/Win-Loss Margins ...............................121 All times Central and subject to change. All home games at Chesapeake Energy Arena. PLAYERS Overtime Results .....................................................................................122 Photo Roster ..............................................................................................10 Team Records .........................................................................................124 Roster ........................................................................................................11 -

Henry Bessemer and the Mass Production of Steel

Henry Bessemer and the Mass Production of Steel Englishmen, Sir Henry Bessemer (1813-1898) invented the first process for mass-producing steel inexpensively, essential to the development of skyscrapers. Modern steel is made using technology based on Bessemer's process. Bessemer was knighted in 1879 for his contribution to science. The "Bessemer Process" for mass-producing steel, was named after Bessemer. Bessemer's famous one-step process for producing cheap, high-quality steel made it possible for engineers to envision transcontinental railroads, sky-scraping office towers, bay- spanning bridges, unsinkable ships, and mass-produced horseless carriages. The key principle is removal of impurities from the iron by oxidation with air being blown through the molten iron. The oxidation also raises the temperature of the iron mass and keeps it molten. In the U.S., where natural resources and risk-taking investors were abundant, giant Bessemer steel mills sprung up to drive the expanding nation's rise as a dominant world economic and industrial leader. Why Steel? Steel is the most widely used of all metals, with uses ranging from concrete reinforcement in highways and in high-rise buildings to automobiles, aircraft, and vehicles in space. Steel is more ductile (able to deform without breakage) and durable than cast iron and is generally forged, rolled, or drawn into various shapes. The Bessemer process revolutionized steel manufacture by decreasing its cost. The process also decreased the labor requirements for steel-making. Prior to its introduction, steel was far too expensive to make bridges or the framework for buildings and thus wrought iron had been used throughout the Industrial Revolution. -

6 X 10 Long Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-15382-9 - Heroes of Invention: Technology, Liberalism and British Identity, 1750-1914 Christine MacLeod Index More information Index Acade´mie des Sciences 80, 122, 357 arms manufacturers 236–9 Adam, Robert 346 Armstrong, William, Baron Armstrong of Adams, John Couch 369 Cragside Aikin, John 43, 44, 71 arms manufacturer 220 Airy, Sir George 188, 360 as hero of industry 332 Albert, Prince 24, 216, 217, 231, 232, 260 concepts of invention 268, 269, 270 Alfred, King 24 entrepreneurial abilities of 328 Amalgamated Society of Engineers, knighted 237–8 Machinists, Millwrights, Smiths and monument to 237 Pattern Makers 286–7 opposition to patent system 250, 267–8 ancestor worship, see idolatry portrait of 230 Anderson’s Institution, Glasgow 113, 114, president of BAAS 355 288, 289 Punch’s ‘Lord Bomb’ 224–5 Arago, Franc¸ois 122, 148, 184 Ashton, T. S. 143 Eloge, to James Watt 122–3, 127 Athenaeum, The 99–101, 369 Arkwright, Sir Richard, Atkinson, T. L. 201 and scientific training 359 Atlantic telegraph cables 243, 245, 327 as national benefactor 282 Arthur, King 15 as workers’ hero 286 Askrill, Robert 213 commemorations of, 259 Associated Society of Locomotive Cromford mills, painting of 63 Engineers and Firemen 288 enterprise of 196, 327, 329 era of 144 Babbage, Charles 276, 353, 356–7, factory system 179 375, 383 in Erasmus Darwin’s poetry 67–8 Bacon, Sir Francis in Maria Edgeworth’s book 171 as discoverer 196 in Samuel Smiles’ books 255, 256 as genius 51, 53, 142 invention of textile machinery 174, 176 bust of 349 knighthood 65 n. -

City of Youngstown Police Department's Weed and Seed

City of Youngstown Police Department’s Weed and Seed Strategy Year Four Evaluation Report Project Manager: Heidi B. Hallas, BSAS Research Associate I/Evaluator Youngstown State University Center for Human Services Development Student Assistants: Julie Robinson, Student Assistant Susan Skelly, Student Assistant Center for Human Services Development Ricky S. George, MS, Associate Director Center for Human Services Development April 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………….1 Methodology…………………………………………………………………………………...1 Weed and Seed Partnerships-Linkages………………………………………………………...2 Highlights………………………………………………………………………………………5 Law Enforcement Goals………………………………………………………………………..6 Community Policing Goals…………………………………………………………………...23 Prevention/Intervention/Treatment Goals…………………………………………………….27 Neighborhood Restoration Goals……………………………………………………………..41 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………44 APPENDIX…………………………………………………………………………………...47 Appendix One - Community Survey Results…………………………………………………48 Appendix Two - Business Survey Results……………………………………………………68 Appendix Three - Block Watch Survey Results……………………………………………...79 Introduction The Center for Human Services Development at Youngstown State University was contracted by the Youngstown Police Department to conduct a program evaluation of the Youngstown Weed and Seed Strategy. The purpose of the evaluation is to provide data for those involved with the Weed and Seed Strategy in order to determine the overall strengths and weaknesses of the program. The goals of -

Keenan Allen, Mike Williams and Austin Ekeler, and Will Also Have Newly-Signed 6 Sun ., Oct

GAME RELEASE PRESEASON WEEK 2 vs. SAN FRANCISCO 49ERS SUN. AUG. 22, 2021 | 4:30 PM PT bolts build under brandon staley 20212020 chargers schedule The Los Angeles Chargers take on the San Francisco 49ers for the 49th time ever PRESEASON (1-0) in the preseason, kicking off at 4:30 p m. PT from SoFi Stadium . Spero Dedes, Dan Wk Date Opponent TV Time*/Res. Fouts and LaDainian Tomlinson have the call on KCBS while Matt “Money” Smith, 1 Sat ., Aug . 14 at L .A . Rams KCBS W, 13-6 Daniel Jeremiah and Shannon Farren will broadcast on the Chargers Radio Network 2 Sun ., Aug . 22 SAN FRANCISCO KCBS 4:30 p .m . airwaves on ALT FM-98 7. Adrian Garcia-Marquez and Francisco Pinto will present the game in Spanish simulcast on Estrella TV and Que Buena FM 105 .5/94 .3 . 3 Sat ., Aug . 28 at Seattle KCBS 7:00 p .m . REGULAR SEASON (0-0) The Bolts unveiled a new logo and uniforms in early 2020, and now will be unveiling a revamped team under new head coach, Brandon Staley . Staley, who served as the Wk Date Opponent TV Time*/Res. defensive coordinator for the Rams in 2020, will begin his first year as a head coach 1 Sun ., Sept . 12 at Washington CBS 10:00 a .m . by playing against his former team in the first game of the preseason . 2 Sun ., Sept . 19 DALLAS CBS 1:25 p .m . 3 Sun ., Sept . 26 at Kansas City CBS 10:00 a .m . Reigning Offensive Rookie of the YearJustin Herbert looks to build off his 2020 season, 4 Mon ., Oct . -

Our School Preschool Songbook

September Songs WELCOME THE TALL TREES Sung to: “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” Sung to: “Frère Jacques” Welcome, welcome, everyone, Tall trees standing, tall trees standing, Now you’re here, we’ll have some fun. On the hill, on the hill, First we’ll clap our hands just so, See them all together, see them all together, Then we’ll bend and touch our toe. So very still. So very still. Welcome, welcome, everyone, Wind is blowing, wind is blowing, Now you’re here, we’ll have some fun. On the trees, on the trees, See them swaying gently, see them swaying OLD GLORY gently, Sung to: “Oh, My Darling Clementine” In the breeze. In the breeze. On a flag pole, in our city, Waves a flag, a sight to see. Sun is shining, sun is shining, Colored red and white and blue, On the leaves, on the trees, It flies for me and you. Now they all are warmer, and they all are smiling, In the breeze. In the breeze. Old Glory! Old Glory! We will keep it waving free. PRESCHOOL HERE WE ARE It’s a symbol of our nation. Sung to: “Oh, My Darling” And it flies for you and me. Oh, we're ready, Oh, we're ready, to start Preschool. SEVEN DAYS A WEEK We'll learn many things Sung to: “For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow” and have lots of fun too. Oh, there’s 7 days in a week, 7 days in a week, So we're ready, so we're ready, Seven days in a week, and I can say them all. -

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU of MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT by WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. WS 1417 Witness Martin Ryan, Kilcroan

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. 1417 DOCUMENT NO. W.S. Witness Martin Ryan, Kilcroan, Kilsallagh, Castlerea, Co. Galway. Identity. Battalion Vice-Commandant. Subject. Activities of Ballymoe Company, Glenamaddy Battalion, North Galway Brigade, 1917-1921. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil. File No S.2749. Form B.S.M.2 STATEMENT BY MR. MARTIN RYAN Kilcroan, Kilsallagh, Castlerea, Co. Galway. I was born in the month of June 1889, at Kilcroan, Kilsallagh, Castlerea, Co. Galway, and educated at Kilcroan National School until I reached the age of about 15 years. I attended the same school during winter months for a few years afterwards. My first association with the Irish Volunteers was in the year 1917. I cannot be more exact with regard to the date. The place was Roscommon town. I remember that I got an invitation to attend a meeting there called for the purpose of reorganising the Volunteers. Accompanied by John Harte from my own locality and Owen O'Neill and Michael Hurley from the Glynsk area, I attended the meeting which on a was held Sunday in a hall in the town. The organisers, as far as I remember; were either Dublin men or they came to the meeting from Dublin. I remember distinctly that there was a force of about 20 R.I.C. outside the hall while the meeting was in progress. They did not interfere with us during or after the meeting, but of course they would know us again. The Ballymoe company was formed soon after, and I became a member of it. -

The Irish Catholic Episcopal Corps, 1657 – 1829: a Prosopographical Analysis

THE IRISH CATHOLIC EPISCOPAL CORPS, 1657 – 1829: A PROSOPOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS VOLUME 1 OF 2 BY ERIC A. DERR THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERISTY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH SUPERVISOR OF RESEARCH: DR. THOMAS O’CONNOR NOVEMBER 2013 Abstract This study explores, reconstructs and evaluates the social, political, educational and economic worlds of the Irish Catholic episcopal corps appointed between 1657 and 1829 by creating a prosopographical profile of this episcopal cohort. The central aim of this study is to reconstruct the profile of this episcopate to serve as a context to evaluate the ‘achievements’ of the four episcopal generations that emerged: 1657-1684; 1685- 1766; 1767-1800 and 1801-1829. The first generation of Irish bishops were largely influenced by the complex political and religious situation of Ireland following the Cromwellian wars and Interregnum. This episcopal cohort sought greater engagement with the restored Stuart Court while at the same time solidified their links with continental agencies. With the accession of James II (1685), a new generation of bishops emerged characterised by their loyalty to the Stuart Court and, following his exile and the enactment of new penal legislation, their ability to endure political and economic marginalisation. Through the creation of a prosopographical database, this study has nuanced and reconstructed the historical profile of the Jacobite episcopal corps and has shown that the Irish episcopate under the penal regime was not only relatively well-organised but was well-engaged in reforming the Irish church, albeit with limited resources. By the mid-eighteenth century, the post-Jacobite generation (1767-1800) emerged and were characterised by their re-organisation of the Irish Church, most notably the establishment of a domestic seminary system and the setting up and manning of a national parochial system. -

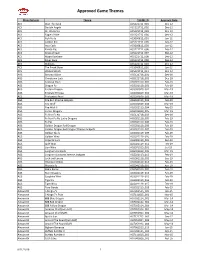

Approved Game Themes

Approved Game Themes Manufacturer Theme THEME ID Approval Date ACS Bust The Bank ACS121712_001 Dec-12 ACS Double Angels ACS121712_002 Dec-12 ACS Dr. Watts Up ACS121712_003 Dec-12 ACS Eagle's Pride ACS121712_004 Dec-12 ACS Fish Party ACS060812_001 Jun-12 ACS Golden Koi ACS121712_005 Dec-12 ACS Inca Cash ACS060812_003 Jun-12 ACS Karate Pig ACS121712_006 Dec-12 ACS Kings of Cash ACS121712_007 Dec-12 ACS Magic Rainbow ACS121712_008 Dec-12 ACS Silver Fang ACS121712_009 Dec-12 ACS Stallions ACS121712_010 Dec-12 ACS The Freak Show ACS060812_002 Jun-12 ACS Wicked Witch ACS121712_011 Dec-12 AGS Bonanza Blast AGS121718_001 Dec-18 AGS Chinatown Luck AGS121718_002 Dec-18 AGS Colossal Stars AGS021119_001 Feb-19 AGS Dragon Fa AGS021119_002 Feb-19 AGS Eastern Dragon AGS031819_001 Mar-19 AGS Emerald Princess AGS031819_002 Mar-19 AGS Enchanted Pearl AGS031819_003 Mar-19 AGS Fire Bull Xtreme Jackpots AGS021119_003 Feb-19 AGS Fire Wolf AGS031819_004 Mar-19 AGS Fire Wolf II AGS021119_004 Feb-19 AGS Forest Dragons AGS031819_005 Mar-19 AGS Fu Nan Fu Nu AGS121718_003 Dec-18 AGS Fu Nan Fu Nu Lucky Dragons AGS021119_005 Feb-19 AGS Fu Pig AGS021119_006 Feb-19 AGS Golden Dragon Red Dragon AGS021119_008 Feb-19 AGS Golden Dragon Red Dragon Xtreme Jackpots AGS021119_007 Feb-19 AGS Golden Skulls AGS021119_009 Feb-19 AGS Golden Wins AGS021119_010 Feb-19 AGS Imperial Luck AGS091119_001 Sep-19 AGS Jade Wins AGS021119_011 Feb-19 AGS Lion Wins AGS071019_001 Jul-19 AGS Longhorn Jackpots AGS031819_006 Mar-19 AGS Longhorn Jackpots Xtreme Jackpots AGS021119_012 Feb-19 AGS Luck -

Smythe-Wood Series B

Mainly Ulster families – “B” series – Smythe-Wood Newspaper Index Irish Genealogical Research Society Dr P Smythe-Wood’s Irish Newspaper Index Selected families, mainly from Ulster ‘SERIES B’ The late Dr Patrick Smythe-Wood presented a large collection of card indexes to the IGRS Library, reflecting his various interests, - the Irish in Canada, Ulster families, various professions etc. These include abstracts from various Irish Newspapers, including the Belfast Newsletter, which are printed below. Abstracts are included for all papers up to 1864, but excluding any entries in the Belfast Newsletter prior to 1801, as they are fully available online. Dr Smythe-Wood often found entries in several newspapers for the one event, & these will be shown as one entry below. Entries dealing with RIC Officers, Customs & Excise Officers, Coastguards, Prison Officers, & Irish families in Canada will be dealt with in separate files. In most cases, Dr Smythe-Wood has recorded the exact entry, but in some, marked thus *, the entries were adjusted into a database, so should be treated with more caution. There are further large card indexes of Miscellaneous notes on families which are not at present being digitised, but which often deal with the same families treated below. ACR: Acadian Recorder LON The London Magazine ANC: Anglo-Celt LSL Londonderry Sentinel ARG Armagh Guardian LST Londonderry Standard BAA Ballina Advertiser LUR Lurgan Times BAI Ballina Impartial MAC Mayo Constitution BAU Banner of Ulster NAT The Nation BCC Belfast Commercial Chronicle NCT -

Causes and Technologies of the Industrial Revolution

FCPS World II SOL Standards: WHII 9a Causes and Technologies of the Industrial Revolution You Mean Most People Used to Live on Farms? Farms to Factories Starting in the middle of the 18th century, technology and lifestyles in many parts of the world changed dramatically. Factories were built, technology developed, populations increased and many people moved from farms to cities to work in a new economy. We call these changes the Industrial Revolution. This began in England but spread to the rest of Western Europe and the United States. Causes of the Industrial Revolution The Industrial Revolution began in England for several reasons. First, there was a large supply of natural resources. Coal and other fossil fuels were used to Spread of Industrialization in Europe create power for factories. Iron ore was used to build Source: http://althistory.wikia.com/wiki/File:OTL_Europe_Industrial_Revolution_Map.png factory equipment and manufactured goods. Another key reason was the British enclosure movement. In England rich landowners bought the farms of poor peasants and separated them with fences. This increased food production but decreased the need for labor on the farms. More people could move to cities and work in factories. During the Industrial Revolution, new technologies and inventions transformed society in many ways. -The spinning jenny was invented by James Hargreaves. It helped turn cotton and wool into thread, speeding the production of textiles. -The steam engine was invented by James Watt. It used burning coal to turn water into steam and generate electricity. This electricity was used to power factories. -Englishman Edward Jenner invented a smallpox vaccine, saving people from this terrible disease. -

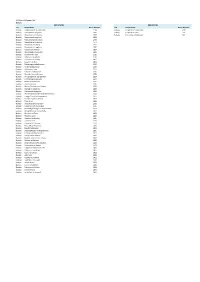

RTP Route Listing Per TCU Galway TCU Route Name Route Number

RTP Route listing per TCU Galway DRT ROUTES RRS ROUTES TCU Route Name Route Number TCU Route Name Route Number Galway Ballymacward to Ballinasloe 1599 Galway Loughrea to Ballinasloe 6081 Galway Portumna to Loughrea 1583 Galway Loughrea to Gort 934 Galway Woodford to Portumna 1593 Galway Portumna to Ballinasloe 547 Galway Portumna to Loughrea 1592 Galway Portumna to Ballinasloe 1573 Galway Woodford to Portumna 1572 Galway Woodford to Galway 1650 Galway Woodford to Loughrea 1587 Galway Portumna to Athlone 1604 Galway Glenamaddy Commuter 1631 Galway Dunmore to Tuam 1620 Galway Athenry to Loughrea 1596 Galway Kilchreest to Galway 1601 Galway Loughrea to Gort 1602 Galway Cappataggle to Ballinasloe 1547 Galway Caltra to Ballinasloe 1584 Galway Ballinasloe Town 1603 Galway Killimor to ballinasloe 1540 Galway Mountbellew to Galway 1575 Galway Annaghdown to Claragalway 1614 Galway Clarinbridge to Galway 1607 Galway Maree to Oranmore 1606 Galway Oranmore Area 1589 Galway Maree/Oranmore to Galway 1590 Galway Mullagh to Loughrea 1608 Galway Kilchreest to Loughrea 1600 Galway Williamstown/Ballymoe to Roscommon 1633 Galway Creggs/Glinsk to Roscommon 1632 Galway Clonbern to Roscommon 1617 Galway Tuam Area 1616 Galway Abbeyknockmoy to Tuam 1531 Galway Killererin Community Bus 1525 Galway Newbridge/Ballygar to Roscommon 1612 Galway Annaghdown to Corrundulla 1624 Galway Headford to Tuam 1622 Galway Headford Area 1623 Galway Headford to Galway 5036 Galway Carna to Casia 1797 Galway Carna to Cill Chiarain 1798 Galway Roscahill to Moycullen 1799 Galway Spiddle