College Coaching Contracts: a Practical Perspective Martin J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Men's Basketball Coaching Records

MEN’S BASKETBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 NCAA Division I Coaching Records 4 Coaching Honors 31 Division II Coaching Records 36 Division III Coaching Records 39 ALL-DIVISIONS COACHING RECORDS Some of the won-lost records included in this coaches section Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. have been adjusted because of action by the NCAA Committee 26. Thad Matta (Butler 1990) Butler 2001, Xavier 15 401 125 .762 on Infractions to forfeit or vacate particular regular-season 2002-04, Ohio St. 2005-15* games or vacate particular NCAA tournament games. 27. Torchy Clark (Marquette 1951) UCF 1970-83 14 268 84 .761 28. Vic Bubas (North Carolina St. 1951) Duke 10 213 67 .761 1960-69 COACHES BY WINNING PERCENT- 29. Ron Niekamp (Miami (OH) 1972) Findlay 26 589 185 .761 1986-11 AGE 30. Ray Harper (Ky. Wesleyan 1985) Ky. 15 316 99 .761 Wesleyan 1997-05, Oklahoma City 2006- (This list includes all coaches with a minimum 10 head coaching 08, Western Ky. 2012-15* Seasons at NCAA schools regardless of classification.) 31. Mike Jones (Mississippi Col. 1975) Mississippi 16 330 104 .760 Col. 1989-02, 07-08 32. Lucias Mitchell (Jackson St. 1956) Alabama 15 325 103 .759 Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. St. 1964-67, Kentucky St. 1968-75, Norfolk 1. Jim Crutchfield (West Virginia 1978) West 11 300 53 .850 St. 1979-81 Liberty 2005-15* 33. Harry Fisher (Columbia 1905) Fordham 1905, 16 189 60 .759 2. Clair Bee (Waynesburg 1925) Rider 1929-31, 21 412 88 .824 Columbia 1907, Army West Point 1907, LIU Brooklyn 1932-43, 46-51 Columbia 1908-10, St. -

Eclectic Guests Highlight Record Dinner Turnout

Page 12 Thursday, February 15, 2018 The Westfield Leader and The Scotch Plains – Fanwood TIMES A WATCHUNG COMMUNICATIONS, INC. PUBLICATION Area stores that carry The Westfield Leader and The Scotch Plains – Fanwood TIMES Westfield Tobacco & News 7-11 of Westfield 7-11 of Mountainside Westfield Mini Mart Kwick Mart Food Store Mountain Deli 108 Elm St. (Leader) 1200 South Ave., W. (Leader/Times) 921 Mountain Ave. (Leader) 301 South Ave., W. (Leader) 190 South Ave. (Times) 2385 Mountain Ave. (Times) 7-11 of Garwood Shoprite Supermarket King's Supermarket Baron's Drug Store Scotch Hills Pharmacy Wallis Stationery Krauszer's 309 North Ave. (Leader) 563 North Ave. (Leader) 300 South Ave. (Leader) 243 E. Broad St. (Leader) 1819 East 2nd St. (Times) 441 Park Ave. (Leader/Times) 727 Central Ave. (Leader) Devil’s Den Eclectic Guests Highlight Record Dinner Turnout By BRUCE JOHNSON Specially Written for The Westfield Leader and The Times This week we’re going to take a Tillman, coach John Wooden. Eric Shaw, boys soccer coach. Johan one-week break from the rigors of Liz McKeon, girls basketball coach Cruyff, Alex Ferguson, Harry WHS athletics, and spend some time (’99). Tommy Hart (grandfather), McAlarney (grandfather). breaking bread with the school’s ath- Derek Jeter, Pat Summitt. Jillian Shirk, future athlete (’26). letes, coaches, alumni and fans. Steve Merrill, historian (’71). Gen- Antonio Brown, Steph Curry, Eli Tonight’s big event is the third erals Stonewall Jackson, Robert E. Manning. mythical Devil’s Den Dinner. We Lee, George Patton. Maria Shirk, future athlete (’29). asked WHS senior athletes, coaches, Don Mokrauer, fan (’63). -

MSU Gamenotes

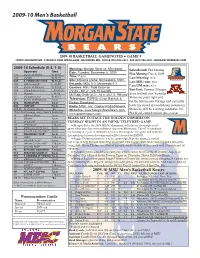

2009-10 Men’s Basketball 2009-10 BASKETBALL GAMENOTES ● GAME 9 SPORTS INFORMATION • 1700 EAST COLD SPRING LANE • BALTIMORE, MD • OFFICE (443) 885-3831 • FAX (443) 885-8307 • MORGANSTATEBEARS.COM 2009-10 Schedule (5-3, 1-0) Matchup: Morgan State vs. Minnesota Opponent Time Series Record: First Meeting Date: Tuesday, December 8, 2009 N13 @Univ. of Albany W, 69-65 First Meeting: Dec. 8, 2009 Time: 7 p.m. N15 @UMBC W, 72-57 Last Meeting: n/a Site: Williams Arena; Minneapolis, Minn. N19 E. TENNESSEE STATE W, 72-61 Last MSU win: n/a N22 @#22 Louisville L, 81-90 Records: MSU 5-3, Minnesota 5-3 n/a N24 @Univ. of Arkansas W, 97-94 Coaches: MSU- Todd Bozeman Last UM win: N28 @Appalachian State L, 93-92 OT (72-44 - 4th yr; 125-79 overall); Fast Fact: Former Morgan D1 @Loyola L, 66-78 UM Tubby Smith (45-28 - 3rd yr; 434-173, 19th year) State football star, Visanthe D5 @Coppin State* W, 80-67 Shiancoe plays tight end D8 @Univ. of Minnesota 7 p.m. Television: ESPNU (Clay Matvick & D12 MANHATTAN 4 p.m. Dickey Simpkins) for the Minnesota Vikings and currently D22 TOWSON 7 p.m. Radio: MSU: n/a; Gopher Radio Network leads his squad in touchdown receptions. D29-30 Dr. Pepper Classic TBA Websites: www.MorganStateBears.com; Shiancoe will be a strong candidate for (Tenn-Chattanooga, Long Island, E. Kentucky) Pro Bowl consideration this season. J4 @Robert Morris 7 p.m. www.gophersports.com J6 @Baylor 7 p.m. BEARS SET TO FACE THE GOLDEN GOPHERS ON J9 @Howard* 8 p.m. -

College of Charleston Coaches 1986-87 Georgia Tech 16-13 Coach Seasons Years W L Pct

COLLEGE OF CHARLE S TON I 2008-09 Cougars Roster NTRODUCT No. Name Pos. Ht. Wt. Class Hometown/Last School 1 Donavan Monroe G 6-1 180 So. Waxhaw, N.C./Fork Union Military Aca. 2 Matt Sundberg F 6-8 195 Fr. Kennnesaw, Ga./Harrison I 3 Andrew Goudelock G 6-1 170 So. Lilburn, Ga./Stone Mountain ON 5 Jermaine Johnson F 6-7 250 Sr. Los Angeles, Calif./Winchendon 11 Dustin Scott F 6-8 220 Sr. Jamestown, S.C./Tallahassee CC 12 Quasim Pugh G 5-11 165 Fr. Oakdale, Conn./St. Thomas More 20 Evan Turkish G 6-1 170 Fr. New Orleans, La./Isidore Newman 21 Jeremy Simmons F 6-8 225 So. Lithonia, Ga./Tucker P. George Benson 30 Tauras Skripkauskas G 6-5 200 So. Vilnius, Lithuania President 31 Marcus Hammond G 6-3 190 Sr. Memphis, Tenn./Brewster Academy S 32 Tony White, Jr. G 6-0 150 Jr. Knoxville, Tenn./Bearden OUTHERN 35 Jordan Turok G 6-0 180 So. Chapin, S.C./Chapin 40 Garrett Campbell F 6-8 230 Jr. Myrtle Beach, S.C./Myrtle Beach 42 Casaan Breeden F 6-8 205 Sr. Clio, S.C./Florida State C 44 Antwaine Wiggins F 6-7 180 So. Greeneville, Tenn./Greeneville ONFERENCE Quick Facts 2008-09 Schedule Location: ...........................................Charleston, S.C., 29409 Founded: ............................................................................. 1770 Date. Opponent Time Enrollment: ......................................................................11,617 Nov. 14 SIU-EDWARDSVILLE (CSS)$ 7 p.m. Nickname: ..................................................................... Cougars Nov. 15 TEMPLE/ETSU$ 11:30 a.m./2 p.m. Joe Hull Colors: ............................................ Maroon, Gold and White Director of Athletics President: ...............................................Dr. -

Coaches Vs Cancer

YOUTH & HIGH SCHOOL TOOLKIT coachesvscancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Coaches vs. Cancer Council LON KRUGER, CHAIR MIKE KRZYZEWSKI University of Oklahoma Duke University MIKE ANDERSON DAVID LEVY University of Arkansas Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. WARNER BAXTER Ameren PHIL MARTELLI St. Joseph’s University JAY BILAS ESPN FRAN MCCAFFERY Come and Play for Us University of Iowa JIM BOEHEIM The American Cancer Society and the National Association of Syracuse University GREG MCDERMOTT Creighton University Basketball Coaches (NABC) have teamed up in the fight against cancer. GARY BOWNE Hickory Christian Academy REGGIE MINTON Each year, youth and high school teams across the country have done NABC TAD BOYLE their part to raise funds and awareness in these efforts. Once again, we University of Colorado GARRY MUNSON Whitney Capital Company, invite schools and leagues to unite with basketball coaches across the MIKE BREY LLC country this season to raise funds to beat cancer. Teams have already University of Notre Dame DAVE PILIPOVICH signed up to participate. JIM CALHOUN Air Force Academy University of Saint Joseph As a coach and leader in your community, we’re asking you to use MICHAEL PIZZO BOBBY CREMINS GCA Advisors, LLC your influence to promote cancer awareness and raise funds for the Retired Head Coach DAVE R OSE American Cancer Society. FRAN DUNPHY Brigham Young University Temple University BO RYAN Don’t sit on the bench. Join in to make a difference in the fight DONNIE EPPLEY Retired Head Coach against cancer. International Association of Approved Basketball BOB SANSONE Officials, Inc. iTrust Advisors LLC ERAN GANOT MIKE SHULT What is Coaches vs. -

LSU Basketball Vs

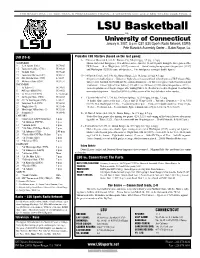

THE BRADY ERA | In 10th YEAR, 6 POSTSEASON TOURN., 3 WESTERN DIV. and 2 SEC TITLES; 2006 FINAL 4 LSU Basketball vs. University of Connecticut January 6, 2007, 8 p.m. CST (LSU Sports Radio Network, ESPN) Pete Maravich Assembly Center -- Baton Rogue, La. LSU (10-3) Probable LSU Starters (based on the last game): G -- 2Dameon Mason (6-6, 183, Jr., Kansas City, Mo.) 8.0 ppg, 3.5 rpg, 1.2 apg NOVEMBER Mason started last four games, 11 in all this season ... Had 14, 13 and 11 points during the three games of the 9 E. A. Sports (Exh.) W, 70-65 HCF Classic ... 14 vs. Wright State (12/27) season est ... Out of starting lineup against Oregon State (12/17) 15 Louisiana College (Exh.) W, 94-41 and Washington (12/20) because of migraines ... Five total games scoring in double figures. 17 Nicholls State W, 96-42 19 Louisiana-Monroe (CST) W, 88-57 G -- 14 Garrett Temple (6-5, 190, So., Baton Rouge, La.) 10.2 ppg, 2.8 rpg, 4.1 apg 25 #24 Wichita State (CST) L, 53-57 Six games in double figures ... Had career highs of seven assists in back-to-back games of HCF Classic (Miss. 29 McNeese State (CST) W, 91-57 Valley, 12/28; Samford 12/29) with just five combined turnovers ... In first seven games had 23 assists and just DECEMBER 7 turnovers ... Career high of 18 at Tulane (12/2) with 17 vs. McNeese (11/29) and at Oregon State (12/17) ... 2 At Tulane (1) W, 74-67 Earned reputation as defensive stopper after holding Duke’s J.J. -

Newsletter Fall 2005.Pmd

Fall 2005 Motor Development discussing a research project she is channel but the air date is not released conducting with overweight children yet. Center Makes News! in West Virginia. She is among the Dr. Carson was selected to be the The staff of the WV Motor first to study the benefits of playing keynote speaker and head trainer for a Development Center has been very Dance-Dance Revolution (DDR), an Cabinet level initiative mandated to busy this year. In addition to active video game that children play Head Start for childhood obesity conducting children’s physical activity with their feet instead of their hands. prevention. She has been working programs, the Center had a very Dr. Carson is studying the effects that with the six state, mid-Atlantic Region successful summer day camp under playing DDR will have on endothelial III of Head Start implementing a pilot the direction of Kerry McKenzie. function of arteries, cholesterol, program known as “I Am Moving, I Camp Choosy focused on good aerobic capacity, and percent fat. Am Learning.” The initiative is based nutrition, active play, and summer Preliminary findings are very on Dr. Carson’s preschool physical FUN. promising. The study has received education curriculum. A significant gift was presented to national attention and will be To learn more about the Motor Center Director, Linda Carson and showcased on the Discovery Health Development Center go to Program Coordinator, Kerry Channel on October 16th at 7:00 pm. It www.bechoosy.org McKenzie. In Spring 2005, Joyce will be re-aired on the Discovery Lang presented the center with a beautiful 6’x 6’ hand stitched red quilt. -

David Cutcliffe Named Walter Camp 2013 Coach of the Year

For Immediate Release: December 5, 2013 Contact: Al Carbone (203) 671-4421 - Follow us on Twitter @WalterCampFF Duke’s David Cutcliffe Named Walter Camp 2013 Coach of the Year NEW HAVEN, CT – David Cutcliffe, head coach of the Atlantic Coast Conference Coastal Division champion Duke University Blue Devils, has been named the Walter Camp 2013 Coach of the Year. The Walter Camp Coach of the Year is selected by the nation’s 125 Football Bowl Subdivision head coaches and sports information directors. Cutcliffe is the first Duke coach to receive the award, and the first honoree from the ACC since 2001 (Ralph Friedgen, Maryland). Under Cutcliffe’s direction, the 20th-ranked Blue Devils have set a school record with 10 victories and earned their first-ever berth in the Dr. Pepper ACC Championship Game. Duke clinched the Coastal Division title and championship game berth with a 27-25 victory over in-state rival North Carolina on November 30. Duke (10-2, 6-2 in the Coastal Division) will face top-ranked Florida State (12-0) on Saturday, December 7 in Charlotte, N.C. The Blue Devils enter the game with an eight-game winning streak – the program’s longest since 1941. In addition, the Blue Devils cracked the BCS standings for the first time this season, and were a perfect 4-0 in the month of November (after going 1-19 in the month from 2008 to 2012). Cutcliffe was hired as Duke’s 21st coach on December 15, 2007. Last season, he led the high- scoring Blue Devils to a school record 410 points (31.5 points per game) and a berth in the Belk Bowl – the program’s first bowl appearance since 1994. -

Grizzly Basketball Yearbook, 1967-1968

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Grizzly Basketball Yearbook, 1955-1992 University of Montana Publications 1-1-1967 Grizzly Basketball Yearbook, 1967-1968 University of Montana (Missoula, Mont. : 1965-1994). Athletics Department Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/grizzlybasketball_yearbooks_asc Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation University of Montana (Missoula, Mont. : 1965-1994). Athletics Department, "Grizzly Basketball Yearbook, 1967-1968" (1967). Grizzly Basketball Yearbook, 1955-1992. 4. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/grizzlybasketball_yearbooks_asc/4 This Yearbook is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Montana Publications at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Grizzly Basketball Yearbook, 1955-1992 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARCHIVES Grizzly Basketball 1 9 6 7 -6 8 University of Montana UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA GENERAL INFORMATION Founded ____________,__________________ ._____ 1893 E nrollm ent_________________________________ 6,500 President______________________ Robert T. Pantzer Nicknames___ ________________ Grizzlies, Silvertips C olors___________________ Copper, Silver and Gold ATHLETIC STAFF Athletic D irector__________________ Jack Swarthout Faculty Representative............ __Dr. Earl Lory Head Basketball Coach_________________ Ron Nord Assistant Basketball -

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee

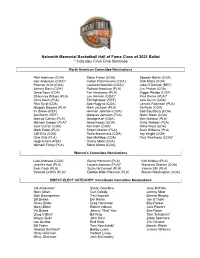

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee North American Committee Nominations Rick Adelman (COA) Steve Fisher (COA) Speedy Morris (COA) Ken Anderson (COA)* Cotton Fitzsimmons (COA) Dick Motta (COA) Fletcher Arritt (COA) Leonard Hamilton (COA)* Jake O’Donnell (REF) Johnny Bach (COA) Richard Hamilton (PLA) Jim Phelan (COA) Gene Bess (COA) Tim Hardaway (PLA) Digger Phelps (COA) Chauncey Billups (PLA) Lou Henson (COA)* Paul Pierce (PLA)* Chris Bosh (PLA) Ed Hightower (REF) Jere Quinn (COA) Rick Byrd (COA) Bob Huggins (COA) Lamont Robinson (PLA) Muggsy Bogues (PLA) Mark Jackson (PLA) Bo Ryan (COA) Irv Brown (REF) Herman Johnson (COA) Bob Saulsbury (COA) Jim Burch (REF) Marques Johnson (PLA) Norm Sloan (COA) Marcus Camby (PLA) George Karl (COA) Ben Wallace (PLA) Michael Cooper (PLA)* Gene Keady (COA) Chris Webber (PLA) Jack Curran (COA) Ken Kern (COA) Willie West (COA) Mark Eaton (PLA) Shawn Marion (PLA) Buck Williams (PLA) Cliff Ellis (COA) Rollie Massimino (COA) Jay Wright (COA) Dale Ellis (PLA) Bob McKillop (COA) Paul Westhead (COA)* Hugh Evans (REF) Danny Miles (COA) Michael Finley (PLA) Steve Moore (COA) Women’s Committee Nominations Leta Andrews (COA) Becky Hammon (PLA) Kim Mulkey (PLA) Jennifer Azzi (PLA) Lauren Jackson (PLA)* Marianne Stanley (COA) Swin Cash (PLA) Suzie McConnell (PLA) Valerie Still (PLA) Yolanda Griffith (PLA)* Debbie Miller-Palmore (PLA) Marian Washington (COA) DIRECT-ELECT CATEGORY: Contributor Committee Nominations Val Ackerman* Simon Gourdine Jerry McHale Marv -

Mallory Men Bullet Points

Mallory Men Bullet Points To: Loyal Mallory Men From: Andy Curtin RE: Letters of Recommendation for Bill Mallory’s Candidacy for College Football Hall of Fame My name is Andy Curtin. I created and ran the Legends Poll for 10 years from 2005 through 2014. We had 23 retired coaches participate over those years. Of this group 21 are in the HOF. Bill Mallory was a charter member and served all 10 years as a voter in the Legends Poll. The roster of Legends Poll coaches is stunning in its composition. Bobby Bowden, Tom Osborne, Frank Broyles, John Cooper, Fisher DeBerry, Bo Schembechler, Terry Donahue, Vince Dooley, Pat Dye, LaVell Edwards, Don James, Hayden Fry, John Ralston, Dick MacPherson, Don Nehlen, John Robinson, Bill Snyder, R.C. Slocum, Gene Stallings, George Welsh, Frank Kush, Bobby Ross…and Bill Mallory. Bobby Ross and Bill are the two non-HOF coaches. Everyone of our Legends Poll coaches believe Bill Mallory belongs in the HOF. However, since 2010 no coach has been granted a waiver for eligibility from the 60% winning percentage minimum rule, despite the fact that there are 31 non-60% coaches in the HOF with over 200 coaches enshrined there. I have been lobbying for Bill for over 4 years now to have the National Football Foundation reinstate the waiver procedure. I believe we have our best chance now because I have created an Index called the Curtin Coach Index (CCI) which I have provided to you herewith. It awards points to coaches for playing Top 25, Top 10 and Top 5 teams and is then averaged by years of service. -

When the Game Was Ours

When the Game Was Ours Larry Bird and Earvin Magic Johnson Jr. With Jackie MacMullan HOUGHTON MIFFLIN HARCOURT BOSTON • NEW YORK • 2009 For our fans —LARRY BIRD AND EARVIN "MAGIC" JOHNSON JR. To my parents, Margarethe and Fred MacMullan, who taught me anything was possible —JACKIE MACMULLAN Copyright © 2009 Magic Johnson Enterprises and Larry Bird ALL RIGHTS RESERVED For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003. www.hmhbooks.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bird, Larry, date. When the game was ours / Larry Bird and Earvin Magic Johnson Jr. with Jackie MacMullan. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-547-22547-0 1. Bird, Larry, date 2. Johnson, Earvin, date 3. Basketball players—United States—Biography. 4. Basketball—United States—History. I. Johnson, Earvin, date II. MacMullan, Jackie. III. Title. GV884.A1B47 2009 796.3230922—dc22 [B] 2009020839 Book design by Brian Moore Printed in the United States of America DOC 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Introduction from LARRY WHEN I WAS YOUNG, the only thing I cared about was beating my brothers. Mark and Mike were older than me and that meant they were bigger, stronger, and better—in basketball, baseball, everything. They pushed me. They drove me. I wanted to beat them more than anything, more than anyone. But I hadn't met Magic yet. Once I did, he was the one I had to beat. What I had with Magic went beyond brothers.