Livestock Show Attendees' Attitudes About

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excel Jan-Dec2015.Xlsx

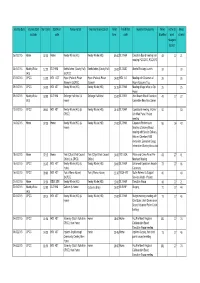

Journey Date Journey start Start time Start Post Places visited Journey finish location Finish Finish Post Reason/s for journey Miles Home to Miles location code time code travelled work claimed mileage to deduct 06.01.2015 Home 07:30 Home Newby Wiske (HQ) Newby Wiske (HQ) 09:00 DL7 9HA Executive Board meeting and 48 27 21 meeting PCC/CEO, PCC/CFO 06.01.2015 Newby Wiske 12:30 DL7 9HA Northallerton (County Hall) Northallerton (County Hall) 15:00 DL7 8AD Alcohol Strategy Launch 39 39 (HQ) (&OPCC) 07.01.2015 OPCC 13:30 HG1 4ST Ripon (Police & Prison Ripon (Police & Prison 14:00 HG4 1LE Meeting with Chairman of 26 26 Museum) (&OPCC) Museum) Ripon Museums Trust 09.01.2015 OPCC 14:30 HG1 4ST Newby Wiske (HQ) Newby Wiske (HQ) 16:15 DL7 9HA Meeting at legal office re Op 25 25 Hyson 09.01.2015 Newby Wiske 18:00 DL7 9HA Solberge Hall Hotel (& Solberge Hall Hotel 21:00 DL7 9ER Joint Branch Board Executive 49 27 22 (HQ) Home) Committee New Year Dinner 12.01.2015 OPCC 09:45 HG1 4ST Newby Wiske (HQ) (& Newby Wiske (HQ) 13:15 DL7 9HA Operational meeting; Victims' 50 50 OPCC) Unit Web Portal Project meeting 14.01.2015 Home 07:30 Home Newby Wiske (HQ) (& Newby Wiske (HQ) 17:00 DL7 9HA Corporate Performance 96 54 42 Home) Scrutiny & Delivery Board; meeting with Service Delivery Adviser; Cleveland/PSD discussion; Executive Group; Information Sharing discussion 15.01.2015 Home 07:15 Home York (City of York Council York (City of York Council 14:00 YO1 6GA Police and Crime Panel Pre- 68 27 41 Offices) (& OPCC) Offices) Meet and Meeting 15.01.2015 OPCC 16:45 -

Trade Stand Brochure 2021.Indd

Tuesday 13 - Friday 16 July 2021 TRADE STAND BROCHURE greatyorkshireshow.co.uk The Great Yorkshire Show was first held in 1838. Since then it has grown to become one of the Visitor Profile leading agricultural shows in the UK, consistently The Great Yorkshire Show delivers you a delivering you a quality audience of around consistently large audience: 130,000 visitors. Age 18-34 :- 24% of 35-54 :- 36% 55-74 :- 36% Visitor 75+ :- 4% Average value at show stands Transaction £89 SEG Profile AB C1 C2 DE 27% 46% 19% 8% Number of Visitors 2018 2019 2017 134,421 135,095 133,542 Statistics from independent research conducted by Buckley Consult at the Great Yorkshire Show 2017 Index of Contents 4 Trade Stand Options & Costs 11 Ocial Advertisement Booking Form 5 Shedding Diagrams 13 Electricity Booking Form 6 Tickets, Passes and Vehicle Labels 15 Water Booking Form 6 Caravan Park Details 16-23 Rules and Regulations 7 Classified Index 24-32 Health and Safety Policy 8-9 Map of 2019 Showground Index of Forms to Complete Return By Checklist Application Form Enclosed 16 April 2021 Risk Assessment Form Enclosed 16 April 2021 Advertisement Booking Form 16 April 2021 Water Booking Form 18 June 2021 (orders received after this date will be charged at a higher rate – please see booking form) Electricity Booking Form 18 June 2021 (orders received after this date will be charged at a higher rate – please see booking form) Show Sta Show & Trade Stands Coordinator Operations Manager Michelle Mackey Nigel Morgan 01423 546204 / [email protected] 01423 546205 / -

Class Records (Fmserver MALTON)

Yorkshire Agricultural Society Tuesday 13 July - Friday 16 July 2021 Patron: HRH The Prince of Wales President: Sir William Worsley Show Director: Charles Mills EQUINE SCHEDULE ENTRIES CLOSE TUESDAY 4 MAY 2021 LATE ENTRIES WILL BE RETURNED Please send your entries to: Livestock & Entries Dept., Yorkshire Agricultural Society, Regional Agricultural Centre, Harrogate, North Yorkshire, HG2 8NZ. Enquiries: Amanda Stoddart-West (01423 546231) [email protected] Jo-Anne Suddaby (01423 546236) [email protected] Jenny Robinson (01423 546206) [email protected] Tel: 01423 541000 Fax: 01423 541414 www.greatyorkshireshow.co.uk The Great Yorkshire Show raises funds for the Yorkshire Agricultural Society to help support farming and the countryside. Registered Charity No: 513238 Company Reg No:1666751 VAT Reg No: 613048081 PLEASE NOTE: THE SCHEDULE IS NOT IN NUMERICAL CLASS ORDER THIS YEAR, DUE TO ADDING THE FOURTH DAY. PLEASE USE THIS INDEX TO LOCATE YOUR SECTION Entry Fees and Prize Money 3 Ladies Side-Saddle Weds 26 Provisional Timetable 6-9 Lead Rein of Hunter Type Fri 40 Cleveland Bay Tues 10 Mini Show Ponies Clydesdale Tues 11 Lead Rein & First Ridden Fri 41 Cobs Weds 30 Mountain and Moorland Coloured Horse & Pony In-hand Weds 28 Ridden Tues 12 Ridden Thurs 38-39 Youngstock Weds 20 Lead Rein & First Ridden Thurs 37 Dales Thurs 34 Regulations 49-60 Dartmoor Weds 21 Retrained Racehorse Weds 29 Donkey Weds 22 Riding Horses Weds 32 Fell Thurs 35 Riding Pony Breeding & Heavy Horse Turnouts All 13 Youngstock Weds 33-34 Highland Thurs 36 Shetland Fri 42 In-Hand Sup. -

Class Records (Fmserver MALTON)

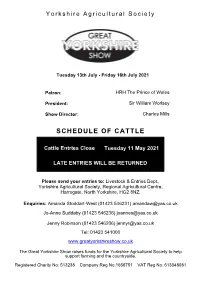

Yorkshire Agricultural Society Tuesday 13th July - Friday 16th July 2021 Patron: HRH The Prince of Wales President: Sir William Worlsey Show Director: Charles Mills SCHEDULE OF CATTLE Cattle Entries : Clos e Tuesday 11 May 2021 LATE ENTRIES WILL BE RETURNED Please send your entries to: Livestock & Entries Dept., Yorkshire Agricultural Society, Regional Agricultural Centre, Harrogate, North Yorkshire, HG2 8NZ. Enquiries: Amanda Stoddart-West (01423 546231) [email protected] Jo-Anne Suddaby (01423 546236) [email protected] Jenny Robinson (01423 546206) [email protected] Tel: 01423 541000 www.greatyorkshireshow.co.uk The Great Yorkshire Show raises funds for the Yorkshire Agricultural Society to help support farming and the countryside. Registered Charity No: 513238 Company Reg No:1666751 VAT Reg No: 613048081 IMPORTANT CHANGES FOR THE 2021 SHOW TUESDAY & WEDNESDAY DAIRY CATTLE & COMMERCIAL BEEF Dairy Cattle and Commercial Beef can arrive at the showground from 11am on Sunday 11th July. The Dairy Cattle and the Commercial Beef Cattle can be removed after 5pm on Wednesday 14th July. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ THURSDAY & FRIDAY PEDIGREE BEEF CLASSES Pedigree Beef Cattle can be brought to the showground from 7pm on Wednesday 14th July and must remain on the showground until 5pm on Friday 16th July. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Exhibitors must not arrive before Wednesday if their allotted judging days are Thursday and Friday or stay later than Wednesday if they were judged on Tuesday and Wednesday unless there are exceptional circumstances. Any request to do so must be made on the entry form stating clearly what the circumstances are and the decision of the Society will be final. -

Equine Schedule

Yorkshire Agricultural Society Tuesday 13 July - Friday 16 July 2021 Patron: HRH The Prince of Wales President: Sir William Worsley Show Director: Charles Mills EQUINE SCHEDULE ENTRIES CLOSE TUESDAY 4 MAY 2021 LATE ENTRIES WILL BE RETURNED Please send your entries to: Livestock & Entries Dept., Yorkshire Agricultural Society, Regional Agricultural Centre, Harrogate, North Yorkshire, HG2 8NZ. Enquiries: Amanda Stoddart-West (01423 546231) [email protected] Jo-Anne Suddaby (01423 546236) [email protected] Jenny Robinson (01423 546206) [email protected] Tel: 01423 541000 Fax: 01423 541414 www.greatyorkshireshow.co.uk The Great Yorkshire Show raises funds for the Yorkshire Agricultural Society to help support farming and the countryside. Registered Charity No: 513238 Company Reg No:1666751 VAT Reg No: 613048081 PLEASE NOTE: THE SCHEDULE IS NOT IN NUMERICAL CLASS ORDER THIS YEAR, DUE TO ADDING THE FOURTH DAY. PLEASE USE THIS INDEX TO LOCATE YOUR SECTION Entry Fees and Prize Money 3 Ladies Side-Saddle Weds 26 Provisional Timetable 6-9 Lead Rein of Hunter Type Fri 40 Cleveland Bay Tues 10 Mini Show Ponies Clydesdale Tues 11 Lead Rein & First Ridden Fri 41 Cobs Weds 30 Mountain and Moorland Coloured Horse & Pony In-hand Weds 28 Ridden Tues 12 Ridden Thurs 38-39 Youngstock Weds 20 Lead Rein & First Ridden Thurs 37 Dales Thurs 34 Regulations 49-60 Dartmoor Weds 21 Retrained Racehorse Weds 29 Donkey Weds 22 Riding Horses Weds 32 Fell Thurs 35 Riding Pony Breeding & Heavy Horse Turnouts All 13 Youngstock Weds 33-34 Highland Thurs 36 Shetland Fri 42 In-Hand Sup. -

POULTRY Schedule & Regulations

Yorkshire Agricultural Society Tuesday 13th - Friday 16th July 2021 Patron: HRH The Prince of Wales President: Sir William Worsley Show Director: Charles Mills POULTRY Schedule & Regulations Thursday 15 July - Poultry ENTRIES CLOSE Poultry – Tuesday 25 May Late entries will not be accepted www.greatyorkshireshow.co.uk The Great Yorkshire Show raises funds for the Yorkshire Agricultural Society to help support farming and the countryside Registered Charity No: 513238 Company Reg No: 1666751 VAT Reg No: 613048081 Regional Agricultural Centre, Harrogate, North Yorkshire, HG2 8NZ POULTRY To be judged on Thursday 15 July 2021 This Show is held in accordance with the rules of The Poultry Club. All Poultry must be penned by 8.30am on Thursday of Show. There is no access into the Showground for vehicles to deliver birds. Birds can be transported to the Poultry Building by trolley from the Poultry Gate at Grey Gate. Vehicles should be par d before birds are penned. This is a Regional Show for the Rare Breed Poultry Society JUDGES Mr A Dowden, Ruislip, MIddlesex Hard Feather Classes Classes 1–8, 29-48 Mr J Heeley, Bradford, West Yorkshire Heavy Breeds Classes Classes 9-15, 64-90 Mr M Barrett, Cum Dyserth, Denbighshire Light Breeds and Rare Breeds Classes Classes 16-28, 49-63 Mr S R Taylor, Preston, Lancashire True Bantam Classes Classes 91-112 Mr J I H Allonby, Kirkby Steven, Cumbria Waterfowl and Trio Classes Classes 113-114, 120-129 Mr I Simpson, Southwell, Nottinghamshire Championship and Egg Classes Classes 130-150 Mr M O’Hara, Cum Dyserth, Denbighshire Juveniles Classes Classes 115-119 ENTRY FEES & PRIZE MONEY A minimum entry fee of £12 has been introduced e.g. -

Yorkshire Agricultural Society Annual Report 2018

YORKSHIRE AGRICULTURAL SOCIETY ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Registered Company Number 1666751 Registered Charity Number 513238 Yorkshire Agricultural Society Report and financial statements for the year ended 31 December 2018 Yorkshire Agricultural Society Report and financial statements for the year ended 31 December 2018 Contents Legal and administrative information .................................................................................................. 1 Members of Council, Trustees, Committees and Subsidiaries ........................................................ 2-4 Trustees' Report .................................................................................................................. 5-17 Independent auditors’ report …………………………………………………………………………… 18-20 Consolidated statement of financial activities ................................................................................ 21 Consolidated and Society balance sheets .......................................................................................... 22 Statement of cashflows ....................................................................................................................... 23 Accounting policies......................................................................................................................... 24-28 Notes to the financial statements ................................................................................................... 29-47 Yorkshire Agricultural Society (Reg. no. 1666751) Legal and administrative information -

Trade Stand Brochure 2020.Indd

Tuesday 14 - Thursday 16 July 2020 TRADE STAND BROCHURE greatyorkshireshow.co.uk The Great Yorkshire Show was first held in 1838. Since then it has grown to become one of the Visitor Profile leading agricultural shows in the UK, consistently The Great Yorkshire Show delivers you a delivering you a quality audience of around consistently large audience: 130,000 visitors. Age 18-34 :- 24% of 35-54 :- 36% 55-74 :- 36% Visitor 75+ :- 4% Average value at show stands Transaction £89 SEG Profile AB C1 C2 DE 27% 46% 19% 8% Number of Visitors 2018 2019 2017 134,421 135,095 133,542 Statistics from independent research conducted by Buckley Consult at the Great Yorkshire Show 2017 Index of Contents 4 Trade Stand Options & Costs 11 Ocial Advertisement Booking Form 5 Shedding Diagrams 13 Electricity Booking Form 6 Tickets, Passes and Vehicle Labels 15 Water Booking Form 6 Caravan Park Details 16-23 Rules and Regulations 7 Classified Index 24-32 Health and Safety Policy 8-9 Map of 2019 Showground Index of Forms to Complete Return By Checklist Application Form Enclosed 06 December 2019 Risk Assessment Form Enclosed 06 December 2019 Advertisement Booking Form 17 April 2020 Water Booking Form 19 June 2020 (orders received after this date will be charged at a higher rate – please see booking form) Electricity Booking Form 19 June 2020 (orders received after this date will be charged at a higher rate – please see booking form) Show Sta Show & Trade Stands Coordinator Operations Manager Michelle Mackey Paul Mendham 01423 546204 / [email protected] 01423 546205 -

SHOW JUMPING Schedule and Regulations

Yorkshire Agricultural Society Tuesday 13th - Friday 16th July 2021 Patron: HRH The Prince of Wales President: Sir William Worsley Show Director: Charles Mills SHOW JUMPING Schedule and Regulations ENTRIES CLOSE Monday 14 June www.greatyorkshireshow.co.uk The Great Yorkshire Show raises funds for the Yorkshire Agricultural Society to help support farming and the countryside Registered CharityNo: 513238 Company Reg No:1666751 VAT Reg No:613048081 Regional Agricultural Centre, Harrogate, North Yorkshire, HG28NZ Tuesday SHOWJUMPING 13TH July THE WILLIAM HANSONSTAKES CLASS 1: Main Ring - Approx Start Time 13.10 Course Walk will be approx 20 minutes beforehand. Under Table A7 Speed 350 mpm. Maximum height of fences 1.50m. For Grade A registered horses, to be the property of, and to be ridden by current members of British Showjumping (Adult, Associate and Junior Members) No rider may ride more than one horse in this competition. This restriction has been imposed to allow as many exhibitors as possible to enter the class in the allocated ring time. Entries may be limited in this class. See Class 5 re selection for Mini Major. A Perpetual Silver Trophy, offered by the late Robert Hanson, in memory of the late William Hanson, will be awarded to the winner of this class. Prizes: 1st: £2,000; 2nd: £1,400; 3rd: £1,000; 4th: £650; 5th: £440; 6th: £300; 7th: £150; 8th: £60. Entry Fee - £60.00 (inc. VAT) Tuesday SHOWJUMPING 13TH July THE BADSWORTH STAKES ACCUMULATOR CLASS 2: Main Ring - Approx Start Time 16.10 Course Walk will be approx 20 minutes beforehand. As British Showjumping Rule 274. -

YAS Newsletter Spring 2019.Indd

Spring 2019 Newsletter At the heart of farming, food and the countryside. Unveiling a new look for the YAS Today the Yorkshire Now with over 130,000 visitors Society said: “A new logo and Agricultural Society can over three days, the iconic a new website will drive the event attracts the best of British Yorkshire Agricultural Society reveal a new look with the livestock and equine competitors forward as well as promoting launch of a contemporary as well as Royal guests and more prominently the work it new logo and new website industry leaders. does. While celebrating our to drive the charity forward. The YAS is at the heart of this heritage and tradition, we want and organising for the next Show to enhance the Society’s profile While the traditional YAS in an exciting and contemporary crest will still be used when begins as one ends. Look out for a new exhibition stand at this way and appeal to the next appropriate, the new logo will generation of farmers and give a modern look as well as year’s Show which will tell the story of YAS and the work it does stakeholders who will continue working across different media our legacy.” platforms including mobile throughout the year; from Farmer phones. Health Checks and education The new website opens with days to running our farm shop the story of the YAS, created Created in 1837, the YAS was and café Fodder, Pavilions of by Leeds animation studio created to celebrate and support Harrogate and Yorkshire Event Northforge. The two-minute film the farming industry, with its first Centre. -

Board of Directors Meeting (To Be Held in Public)

Agenda Board of Directors Meeting (to be held in Public) will be held on Wednesday, 31 March 2021 from 9.00am at the Pavilions, Great Yorkshire Show Ground, Harrogate North Yorkshire, HG2 8QZ AGENDA Item Item Lead Action Paper Time No. 1.0 Welcome and Apologies for Absence Chairman Note Verbal 9.00 2.0 Patient Story Deputy Chief Note Verbal Nurse 3.0 Declarations of Interest and Register of Chairman Note Attached Interests To declare any new interests and any interests in relation to open items on the agenda 4.0 Minutes of the Previous Board of Directors Chairman Approve Attached meeting held on 27 January 2021 5.0 Matters Arising and Chairman Discuss Verbal Action Log Attached 6.0 Overview by the Chairman Chairman Discuss/ Verbal 9.40 Note 7.0 Chief Executive Report Chief Executive Discuss/ Attached 9.45 Note 7.1 Corporate Risk Register/Board Assurance Executive Note/ Attached Framework Directors Discuss/ 7.2 Integrated Board Report Chief Executive Discuss/ Attached Note/ Approve 7.3 Senior Management Team Chair’s Report Chief Executive Note Attached 8.0 Integrating Care Update Report Chief Executive Discuss/ Attached 10.00 Note 8.1 Primary Care Networks/HARA Update Medical Director Discuss/ Attached Report Note 9.0 People and Culture Committee Chair’s People and Discuss/ Attached 10.10 Report Culture Note Committee Chair 9.1 Director of Workforce and Organisational Director of Note/ Attached Development Report Workforce and Discuss/ Organisational Agree Development Board of Directors Meeting -31 March 2021 - held in Public-31/03/21 1 -

Wool-Schedule-2021.Pdf

SHEEP The Showground will be open for the acceptance of MV Accredited sheep from 11am on Sunday 11th July. Animals entered in the MV Sheep classes must be in the Showground no later than 6pm on Monday 12th July and must remain until 5pm on Wednesday 14th July. Non Accredited Sheep can arrive after 7pm on Wednesday and must remain until 5pm on Friday 16th July. *Butchers Lambs see page 30 Please Note: Unless otherwise stated, untrimmed means no interference with the fleece at all. TIMETABLE (Subject to change) TUESDAY 8.30am MV Accredited Sheep Breed Classes WEDNESDAY 9.30am ,QWHUEUHHGMV 6XSUHPH&KDPSLRQVKLS followed by ,QWHUEUHHGMV 6KHHS3DLUV&KDPSLRQVKLSV 9.00am Wool Fleece Classes from Accredited breeds 12 noon Wool on the Hoof MV Accredited Competition 2.30pm Young Handlers MV Accredited Classes THURSDAY 8.30am Non Accredited Sheep Breed Classes 9.00am Wool Fleece Classes from Non Accredited Breeds 9.30am Commercial Female Championship followed by ,QWHUEUHHGNon Accredited 6XSUHPH&KDPSLRQVKLS FRIDAY followed by ,QWHUEUHHGNon Accredited 6KHHS3DLUV&KDPSLRQVKLSV 12 noon Wool on the Hoof Non Accredited Competition 2.30pm Young Handlers Non Accredited Classes PSGH SHEEP AND GOAT HEALTH SCHEME Please would exhibitors take careful note of the designation of each breed. MV Accredited Non Accredited AOP Continental/Native Breeds AOP Down Breeds Leicester Longwool (for 2021) Beltex AOP Longwool Breeds Lincoln Longwool Bleu Du Maine AOP Primitive Lonk Blue Texel AOP Pedigree Hill or Heath Masham Border Leicester Blackface Mule British Berrichon Bluefaced Leicester North Country Cheviot British Charollais Butchers Lambs Oxford Down British Rouge Clun Forest Rough Fell Dorset Horn/Poll Dorset Dalesbred Ryeland Dutch Spotted Derbyshire Gritstone Ryeland - Coloured Hampshire Down Halfbred Female x Term.