The Influence of Identity on Travel Behaviour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television Academy

Television Academy 2014 Primetime Emmy Awards Ballot Outstanding Directing For A Comedy Series For a single episode of a comedy series. Emmy(s) to director(s). VOTE FOR NO MORE THAN FIVE achievements in this category that you have seen and feel are worthy of nomination. (More than five votes in this category will void all votes in this category.) 001 About A Boy Pilot February 22, 2014 Will Freeman is single, unemployed and loving it. But when Fiona, a needy, single mom and her oddly charming 11-year-old son, Marcus, move in next door, his perfect life is about to hit a major snag. Jon Favreau, Director 002 About A Boy About A Rib Chute May 20, 2014 Will is completely heartbroken when Sam receives a job opportunity she can’t refuse in New York, prompting Fiona and Marcus to try their best to comfort him. With her absence weighing on his mind, Will turns to Andy for his sage advice in figuring out how to best move forward. Lawrence Trilling, Directed by 003 About A Boy About A Slopmaster April 15, 2014 Will throws an afternoon margarita party; Fiona runs a school project for Marcus' class; Marcus learns a hard lesson about the value of money. Jeffrey L. Melman, Directed by 004 Alpha House In The Saddle January 10, 2014 When another senator dies unexpectedly, Gil John is asked to organize the funeral arrangements. Louis wins the Nevada primary but Robert has to face off in a Pennsylvania debate to cool the competition. Clark Johnson, Directed by 1 Television Academy 2014 Primetime Emmy Awards Ballot Outstanding Directing For A Comedy Series For a single episode of a comedy series. -

Winter Escapes on Display

ISSUE 3 (133) • 21-27 JANUARY 2010 • €3 • WWW.HELSINKITIMES.FI DOMESTIC INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS CULTURE EAT & DRINK More Haiti Expat DocPoint: Testing options for left in forum Against ready-made first graders carnage gathers mainstream meals page 4 page 7 page 8 page 15 page 16 among others, those in danger of be- ing alienated with society should be Tighter helped while there is still time. Pent- Winter escapes on display ti Partanen, the Interior Ministry’s Director-General of the Department PETRA NYMAN ten includes trips abroad or within el encompasses literally of slower security for Rescue Services, also emphasised HELSINKI TIMES Finland,” she says. modes of travelling, such as biking that schools are not apart from the Nonetheless, the means of trav- or hiking, where speed travel refers for schools rest of society. “Actions related on- IT'S THAT time of year again, when elling have changed with the eco- to trips that take the holiday goer to ly to schools and educational institu- one can escape the winter and take nomic situation, with an increased his destination and back as swiftly PERTTI MATTILA – STT tions aren’t suffi cient. The prevention a trip to the Travel Fair, Matka 2010, emphasis on thrift. Domestic trav- as possible. MICHAEL NAGLER – HT of risks and risky behaviour requires at the Helsinki Fair Centre. Around el and trips to nearby countries are If there can be any positive out- broad socio-political action.” 1,200 exhibitors representing over popular choices at the moment. Also comes of the current economic SCHOOLS should have cameras and The report on the improvement of 70 countries will apppear at the fair. -

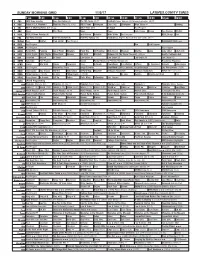

Sunday Morning Grid 11/5/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/5/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Denver Broncos at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Champion Give (TVG) Champion Nitro Circus Å Skating 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Los Angeles Rams at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Bulletproof Monk ›› 18 KSCI Paid Program The Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Martha Jazzy Julia Child Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Motown 25 (My Music Presents) (TVG) Å Huell’s California Adv 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Are Solar Panels Coming to Foley?

Serving the greater NORTH, CENTRAL AND SOUTH BALDWIN communities Fairhope residents paint rocks for positivity PAGE 5 City votes to establish resource The Onlooker officer PAGE 3 JUNE 14, 2017 | GulfCoastNewsToday.com | 75¢ Children meet a chocolate skunk at library’s summer reading event Are solar panels coming to Foley? Riviera Utilities in early talks early stages, DeBell and his core team at Riviera have already begun seeking out of bringing solar to the city locations that may be used for the solar array. By JESSICA VAUGHN “I just wanted to introduce this idea, [email protected] we’re not looking for any action today,” DeBell stressed. “We have to negotiate FOLEY — Could Foley soon be home some agreements on who’s going to own to a new array of solar panels? That is what, how the agreements are going the hope of Tom DeBell, the General to work, and what land it’s going to be Manager and CEO at Riviera Utilities. on. But as to what our message is with DeBell came before the Foley council on this project, it’s that we want to be the Monday, June 5, to introduce the idea of local leader in doing this, and I see this placing an array of solar panels at a yet as a great opportunity for us to partner undecided location. between Riviera, the city, and bring the “I just wanted to introduce this con- schools into it.” cept to you,” DeBell began. “We’ve got If the panels were to come, AMEA an opportunity to get the community would do an array like the one that they solar, and the good news about it is we set up in Montgomery, which is a 50KW can do it at practically no cost to us.” array. -

Sanction Snapback @Midnight Sept 20

TWITTER SPORTS @newsofbahrain WORLD 9 Hurricane Laura slams southwestern Louisiana INSTAGRAM Djokovic cruises /nobmedia 28 into semis at US LINKEDIN FRIDAY newsofbahrain AUGUST, 2020 Open tuneup 210 FILS WHATSAPP ISSUE NO. 8579 Novak Djokovic beat 3844 4692 Jan-Lennard Struff to FACEBOOK advance into the last /nobmedia four of the ATP and MAIL WTA Western & South- [email protected] ern Open| P 12 WEBSITE newsofbahrain.com Kate Winslet says ‘Contagion’ role helped her prepare for pandemic 11 CELEBS BUSINESS 8 BBK, Ithmaar Holding to discuss acquisition plans Israel’s top court rules for removal of settler homes from Sanction snapback Palestinian land Reuters | Jerusalem @midnight Sept 20 srael’s Supreme Court Iruled yesterday that a cluster of homes in a Jew- US Secretary of State tweets timing of Iran sanctions snapback ish settlement outpost in the occupied West Bank was built on privately owned TDT | agencies Palestinian land and must therefore be removed. ealing a heavy blow to Accepting a petition by Iran’s nuclear ambi- Palestinian plaintiffs, Isra- tions, the US Secretary Last week, the US triggered D the 30-day process to el’s top court overturned a of State Mike Pompeo yesterday 2018 District Court ruling confirmed that the US would restore virtually all @ which had broken judicial restore all UN sanctions on Iran UN sanctions on Iran after ground by recognising the at midnight GMT on September the Security Council failed Mitzpe Kramim settlers’ 20. to uphold its mission to claim to the land, despite “Last week, the US triggered maintain international it being owned by Palestin- the 30-day process to restore ians. -

Nelson's Hardware

NORTH WOODS A SPECIAL SECTION OF THE VILAS COUNTY NEWS-REVIEW POSTAL PATRON Nelson’s ACE ISTHEPLACE ACE AND THE THREE LAKES NEWS PRSRT STD ECRWSS U.S. Postage • HALLMARK CARDS • LAWN & GARDEN SUPPLIES • HAND & POWER TOOLS • PROPANE FILLING • VAST BATTERY SELECTION BATTERY FILLING •VAST •PROPANE & GARDENSUPPLIES•HANDPOWERTOOLS • HALLMARKCARDS • LAWN PAID • PLUMBING & ELECTRICAL SUPPLIES & FIXTURES • AUTOMOTIVE SUPPLIES • KEYS DUPLICATED •CLEANING SUPPLIES SUPPLIES•KEYSDUPLICATED AUTOMOTIVE SUPPLIES &FIXTURES• • PLUMBING&ELECTRICAL Saturday, Permit No. 13 Jan. 23, 2016 Eagle River STIHL (715) 479-4421 © Eagle River Publications, Inc. 1972 THE PAUL BUNYAN OF NORTH WOODS ADVERTISING When you need quality products and friendly, professionalservice. When youneedqualityproductsandfriendly, Depend on the people at Nelson’s forallyourneeds. Depend onthepeople atNelson’s VALSPAR PAINTS VALSPAR UpcomingUpcoming EventsEvents andand Hardware PromotionsPromotions PROGRESS ISSUE Deadline Jan. 29 PROPANE FILLING PROPANE 606 E. Wall, Eagle River 715-479-4496 606 E. Wall, Deadline for Open 7days aweektoserveyou HEADWATERS AREA GUIDE color pages is Feb. 24 11th Annual PONDPOND VISIT US SNOWBLOWERS Home of the Fastest Shaved Ice Track CHAMPIONSHIPSCHAMPIONSHIPS SOON in Wisconsin! Friday & Saturday, Feb. 12 & 13 F Held on the West Bay Dollar EB 7 Eagle of Little St. Germain Lake Lake . 5, 6 & River NORTH WOODS TRADER Saturday, Jan. 23, 2016 Page 2 UNDER NEW OWNERSHIP! FEATURED RESTAURANT OPEN DAILY AT 11 A.M. Char-Grilled Sandwiches • Made-to-Order Pizzas Tuesday Nights – Asian Appetizers Eagle Lanes and Lounge offers COSMIC BOWLING FRI. & SAT. NIGHTS HAPPY HOUR 4-6 p.m. Mon.-Fri. SATURDAY, JAN. 23 SUNDAY, JAN. 31 bowling, food, entertainment “SICK AND WRONG” “DIAMOND PEPPER” 8 p.m. -

Complete-Board-Packet-1.Pdf

AGENDA BOARD OF DIRECTORS Thursday, March 26, 2020 1. CALL TO ORDER AND ROLL CALL 2. AWARDS AND COMMENDATION 3. COMMITTEE CHAIRPERSON REPORTS Finance Committee – Richard Wilson Service Committee – Adairius Gardner 4. CONSENT AGENDA AGENDA ACTION ITEM A – 1: Consideration and Approval of Minutes from February 27, 2020 Board Meeting AGENDA ACTION ITEM A – 2: Consideration and Approval of Microsoft Licensing Annual Renewal AGENDA ACTION ITEM A – 3: Consideration and Approval of Environmental Services 5. REGULAR AGENDA AGENDA ACTION ITEM A – 4: Consideration and Approval of Temporary Tax Anticipation Borrowing of $20,000,000 AGENDA ACTION ITEM A – 5: Consideration and Approval of Emergency Authority AGENDA ACTION ITEM A – 6: Consideration and Approval of Ratification of Emergency Purchases 6. INFORMATION ITEMS INFORMATION ITEM I – 1: Consideration of Receipt of the Finance Report for February 2020 INFORMATION ITEM I – 2: COVID-19 Department Updates INFORMATION ITEM I – 3-7: Department Report 7. ADJOURN Indianapolis Public Transportation Corporation dba IndyGo 1501 W. Washington Street Indianapolis, IN 46222 www.IndyGo.net Awards & Commendation Recognition for March 2020 To: Indianapolis Public Transportation Corporation Board of Directors From: President/CEO, Inez P. Evans Date: March 26th, 2020 March 2020 Awards & Commendations Employee Position Recognition Stella Williams Fixed Route Operator Above & Beyond Service Darryl Carter Facility Maintenance Technician 35 Years of Service Charles Summers Vehicle Maintenance Supervisor 40 Years of -

Cutting Edge 3Rd Edition Pre-Intermediate Wordlist

Cutting Edge 3rd Edition Pre-intermediate Wordlist Cutting Edge 3rd Edition Pre-intermediate Wordlist Part of Headword Page speech Pronunciation German French Italian Example Unit 1 The town offers plenty of opportunities for sporting activity 6 n [C] /ækˈtɪvəti/ Aktivität activité attività activities. faire de la andare in cycle 6 v [I] /ˈsaɪkəl/ radfahren She cycles to school. bicyclette bicicletta diskutieren, discuss 6 v [T] /dɪˈskʌs/ discuter discutere I can always discuss my problems with my sister. besprechen evening class 6 n [C] /ˈiːvnɪŋ klɑːs/ Abendschule cours du soir scuola serale Next year, I'm going to do an evening class. /ˈfeɪvərət,ˈfeɪvrɪt favourite 6 adj Lieblings- préferé favorito We chose Joe's favourite music for the party. / free time 6 n [U] /friː taɪm/ freie Zeit temps libre tempo libero I never have any free time. go out 6 phr v /gəʊ aʊt/ ausgehen sortir uscire Did you go out with your friends last Friday? gym 6 n [C] /dʒɪm/ Fitnessstudio gym deporte I go to the gym twice a week. instrument 6 n [C] /ˈɪnstrəmənt/ Instrument instrument istrumento Do you play any musical instruments? tempo libero, leisure 6 n [U] /ˈleʒə/ Freizeit loisir How do you spend your leisure time? ricreativo… live 6 adj /laɪv/ live live, public live, in diretta You can see the band live tomorrow night. news 6 n [U] /njuːz/ Nachrichten les nouvelles notiziario I usually listen to the news on the radio. online 6 adj, adv /ˌɒnˈlaɪn/ online en ligne online an online teaching programme percent 6 adj, adv, n /pəˈsent/ Prozent pourcent percento He needs 70 percent of the vote to win. -

Graduate School of Arts and Sciences 2016–2017

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Programs and Policies 2016–2017 Graduate School ofGraduate Arts and Sciences 2016 –2017 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 112 Number 5 July 15, 2016 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 112 Number 5 July 15, 2016 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 status as a protected veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Kimberly M. Go≠-Crews University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and protected veterans. -

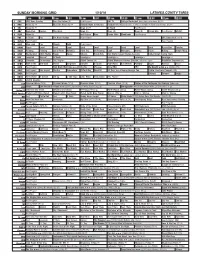

Sunday Morning Grid 1/10/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/10/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program OK! TV College Basketball Ohio State at Indiana. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å Football Night in America Football NFC Wildcard Game Seattle Seahawks at Minnesota Vikings. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC Rock-Park Explore This Week News (N) News (N) News (N) Ocean Mys. Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Pastor Mike Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Paid Program UFC Embedded (TV14) 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Cook Moveable Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Raggs Space Edisons Travel-Kids Doc Martin Seven Grumpy Seasons Father Brown Saving Souls 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Tigres República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Paul Blart: Mall Cop ›› (2009) (PG) Choques Zona NBA XRC We Bought a Zoo ›› (2011) (PG) 50 KOCE Odd Squad Odd Squad Martha Cyberchase Clifford-Dog WordGirl 21 Days to a Slimmer Younger You Il Volo: Live From Pompeii (TVG) 52 KVEA Paid Program Enfoque Enfoque Jungle 56 KDOC Perry Stone In Search Lift Up J. -

UNDER the SKIN Update on the Global Crisis for Donkeys and the People Who Depend on Them

UNDER THE SKIN Update on the global crisis for donkeys and the people who depend on them. NOVEMBER 2019 CONTENTS FOREWORD BY MIKE BAKER ........................................................................4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................6 THE EJIAO INDUSTRY .......................................................................................10 A CRISIS FACING GLOBAL DONKEY POPULATIONS ..........12 ANIMAL WELFARE ................................................................................................14 LIVELIHOODS ...........................................................................................................20 WOMEN .........................................................................................................................24 ENVIRONMENT .......................................................................................................26 OVERVIEW OF THE SKIN TRADE: A GLOBAL THREAT TO DONKEY WELFARE ..................................30 ILLEGALITY IN THE TRADE ...........................................................................32 LINKS TO OTHER CRIMINALITY ................................................................36 BIOSECURITY ............................................................................................................38 OPPOSITION TO THE TRADE .....................................................................42 FARMING .......................................................................................................................46 -

Homores Spar' Ersistent Sto,Pn Political Cam, ,Nteres

I PAC I Fie L U THE RAN U N I V E R 5 I T Y WINTER 2000 · 200 1 School of Education integrates cutting-edge technology without losing the human touch, page 5 Lutes give-and get-the gift of life through a lung lobe transplant, page 6 Fullbright Scholars gain a global perspective, page 7 .. spar' homores ersistent l cam, ,Pn politica ,nteresS tO - ohr , -- MiSS M omores n't st g Soph e( did '"'un e- verSl. t:¥ d essfu\l'l I Ini s�cc host a e� c . .. sentativ '"'::\te ntIal preside pus ---11 cam �r an a ,.. 1 \ I. I. PA CIFIC LUTHERAN UNI ...., E RS'ITY c ne c Ie � tTl\( ,Dll0 Greg Brewis I, Drew Brown w Drew Brown, Greg Brewis, Kalnerine Hedlond 'as and Lauro (Ritchie) GiHord '00 G r'HI( Dt (iN All concerts gre in Logerquln Cotlcert Coli 253-535-7762 Or email The Office 0' Admissions hos confirmed Cerrolyn Reed Barrill Hall unlu� otherwise noted. Times O1'Id comm,[email protected] regional receplion.$ in the following ticket pric� vory; contoct 253-536-5 ' '6 cities, ond more will � scheduled! Coli H OOR PHEA or '-877-254-700 J "Uncommon Wo men and Others" 253-535-71 5' or , -800-274-6758 for Chns TlJll1bllsch An Alpho Psi Omega production, pro more informor;on. CL; S �OlfS ja>Jua.,)' / / duced by senior Dahli Langer. Anchorage Joni Nien Northwest Wind Conductors Five performonces, including a student Bellevue/Seottle Symposium preview on Jon. 31 at 8 p.m., shows on on Billings Feb.