Genomic Characterisation and Conservation Genetics of the Indigenous Irish Kerry Cattle Breed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In This Issue

the Practical Farmer A quarterly publication of Practical Farmers of Iowa Vol. 27, No. 1 | Winter 2012 Wyatt Wheeler hides in the hay at a pasture walk held at Jake and Amber Wheeler’s farm near Monroe this winter. In this issue How specialty crops can supplement farm income Savings Incentive Program: 25 new farmers embark on 2-year quest Field crops: Profit more by using less, without sacrificing yield Special 2012 PFI Annual Conference photo section Solar PV pays off for PFI members PFI Board of Directors We love to hear from you! Please feel free to contact your board members or PFI staff . Contents DISTRICT 1 (NORTHWEST) Gail Hickenbottom, Treasurer David Haden 810 Browns Woods Dr . Letter from the Director . 3 4458 Starling Ave . West Des Moines, IA 50265 Primghar, IA 51245 515 .256 .7876 712 .448 .2012 Horticulture . 4–5 highland33@tcaexpress .net ADVISORY BOARD Dan Wilson, PFI Vice-President Larry Kallem 2011 Beginning Farmer Retreat . .6–7 4375 Pierce Ave . 12303 NW 158th Ave . Paullina, IA 51046 Madrid, IA 50156 712 .448 .3870 515 .795 .2303 PFI Leaders . 8–9 the7wilsons@gmail .com Dick Thompson 2035 190th St . DISTRICT 2 (NORTH CENTRAL) Boone, IA 50036 Savings Incentive Program . .10–11 Sara Hanson 515 .432 .1560 2505 220th Ave . Field Crops . .12–13 Wesley, IA 50483 PFI STAFF 515 .928 .7690 dancingcarrot@yahoo .com For general information and staff Climate Change . 14–15. connections, call 515.232.5661. Tim Landgraf, PFI President Individual extensions are listed in 1465 120th St . 2012 PFI Annual Conference . 16-19 Kanawha, IA 50447 parentheses after each name. -

"First Report on the State of the World's Animal Genetic Resources"

Country Report of Australia for the FAO First Report on the State of the World’s Animal Genetic Resources 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................................5 CHAPTER 1 ASSESSING THE STATE OF AGRICULTURAL BIODIVERSITY THE FARM ANIMAL SECTOR IN AUSTRALIA.................................................................................7 1.1 OVERVIEW OF AUSTRALIAN AGRICULTURE, ANIMAL PRODUCTION SYSTEMS AND RELATED ANIMAL BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY. ......................................................................................................7 Australian Agriculture - general context .....................................................................................7 Australia's agricultural sector: production systems, diversity and outputs.................................8 Australian livestock production ...................................................................................................9 1.2 ASSESSING THE STATE OF CONSERVATION OF FARM ANIMAL BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY..............10 Major agricultural species in Australia.....................................................................................10 Conservation status of important agricultural species in Australia..........................................11 Characterisation and information systems ................................................................................12 1.3 ASSESSING THE STATE OF UTILISATION OF FARM ANIMAL GENETIC RESOURCES IN AUSTRALIA. ........................................................................................................................................................12 -

Jan 32013.Qxd 7/28/2017 3:06 PM Page 1

Aug 3, 2017_Jan 32013.qxd 7/28/2017 3:06 PM Page 1 South Carolina MARKET BULLETIN South Carolina Department of Agriculture Volume 91 August 3, 2017 Number 15 Next Ad Deadline: August 8, 2017, Noon agriculture.sc.gov Market Bulletin Office: 803-734-2536 Seasonal Featured Products Hugh E. Weathers Commissioner South Carolina Photo by Jill Derrick State Farmers Market The Land family not only grow their own fruit, they also ferment it, distill it, bottle it, label it 3483 Charleston Hwy. and sell it at the Chattooga Belle Farm Distillery, which is one of the many facets of their farm. West Columbia, SC 29172 Advocates 803-737-4664 cantaloupes, peaches, squash, Chattooga Belle Farm: Paradise in the Upstate for Agriculture tomatoes, watermelons LONG CREEK--Chattooga Belle Farm’s of more caregivers, so Land is continuously Twelve years ago, an effort Greenville most valuable assets are intangible: the joy seeking more farm workers and creating jobs to establish a coalition of State Farmers Market 1354 Rutherford Rd. and commitment of the family who own it, the in the Upstate. industry organizations to Greenville, SC 29609 stunning views, and the diversity that keeps Land manages the farming, building, retail help market and promote 864-244-4023 people coming back to this paradise. and service divisions of the business. He says South Carolina products bedding plants, dairy products, When Ed Land decided in 2008 that it was when you are operating a business, it is beyond the normal scope flowers, peaches, watermelons time for a career change, he turned his eyes your job to be a part of every aspect of that of the Department was towards 138 acres of land in Oconee County. -

2001 Fall ADCA Dexter Bulletin

Regional Directors Aane.. ic a n Region I Missouri and Jllinoi. J ohn Knoche. RR # I, Box 214A, LaGrange, MO 63448 Dexte.. Cattle (573) 655-4152 knot:[email protected] Term Expires: 11/2003 Association Region 2 Oregon and Idaho Anna Poole, 13474 Agate Road, Eagle Point. OR 97524 26804 Ebenezel" (541) 826-3467 [email protected] Term Expjres: I 1/2003 Concol"dia, MO 64020 Region 3 Washington, British Columbia, Hawaii, and Alaska Mark Youngs, 19919 - 80th Avenue, N.E., Bothell, WA 98011 (206) 489-1492 Term Expires: 11/2003 2001 Officers Region 4 Colorado, Nebraska. Wyoming, and Utah President Carol Am1 Trayno1·, 749 24 3/4 Road, Grand Junction, CO g 1505 Patrick Mitchell (970) 241-2005 [email protected] Term Expires: 11/2003 7164 Barry Street Hudsonvill e. M l 49426 Region 5 Montana, Alberta, and Saskatchawan (616) 875-7494 Allyn Nelson, Box 2. Colinton, Alberta, Canada TOG ORO shamrockacres@ hotmai I .com (780) 675-9295 [email protected] Term Expires: I I /2003 Vice President Region 6 Kansas. Oklahoma. and Texas Kathleen Smith Marvin Johnson . P.O. Box 441. Elkhart. KS 67950 351 Lighthall Road (580) 696-4836 papnjohn @clkhart.com Term Expires: I 1/200 I Ft. Plain, NY 13339 (5 18) 993-2823 Region 7 lndiana, KenLucky. and Ohio Kesmith @telenct.nct Sta n Cass. 19338 Pigeon Roost Rd., Howard. OH 43028 (740) 599-2928 [email protected] Term Expires: 11/200 I Secretarv- Treasurer Rosemary Fleharty Region 8 Alabama. Arkansas. Georgia. Florida. Louisiana. Mississippi. N. Carolina. 26804 Ebenezer S. Carolina, and Tenne~see Concordia. -

Detecting and Managing Suspected Admixture and Genetic Drift in Domestic Livestock: Modern Dexter Cattle - a Case Study

Detecting and managing suspected admixture and genetic drift in domestic livestock: modern Dexter cattle - a case study Timothy C Bray Cardiff University C a r d if f UNIVERSITY PRIFYSCOL C a e RDY|§> A dissertation submitted to Cardiff University in candidature for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy UMI Number: U585124 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U585124 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Table of Contents Page Number Abstract I Declaration II Acknowledgements III Table of Contents IV Chapter 1. Introduction 1 1. introduction 2 1.1. Molecular genetics in conservation 2 1.2. Population genetic diversity 3 1.2.1. Microsatellites 3 1.2.2. Within-population variability 4 1.2.3. Population bottlenecks 5 1.2.4. Population differentiation 6 1.3. Assignment of conservation value 8 1.4. Genetic admixture 10 1.4.1. Admixture affecting conservation 12 1.5. Quantification of admixture 13 1.5.1. Different methods of determining admixture proportions 14 1.5.1.1. Gene identities 16 1.5.1.2. -

1998 September-October ADCA Dexter Bulletin

The Dexter Bulletin September I October, 1998 A chronological account of the World Dexter Congress by Wes and Jane Patton Note' The following is information taken from our notes taken during the congress and may vary somewhat from the written proceedings when they arrive. We thought that our members who were not able to attend might like to know about some of the things we experienced during this well planned and expertly conducted conference. AUGUST 27 -Jane and I arrived at Cirencester, England and the Royal Agricultural College on the evening of August 27 after enjoying the b·eauty and heritage of the Cotswold area of England. We had arrived in London on the 24th and rented a car and headed north to the center of sheep country. Driving on the left side of the road proved to be a challenge, but with some good maps and Jane's expert copiloting we soon were enjoying a new The chamr>ion cow with her owner Di Smith of Dover. scene at every turn. Upon arrival at the Congress we finally met "the other" Rosemary, Rosemary Brown, who played a major part in the expert job of organizing the first World Dexter Congress. What a delightful person she is and immediately she started to introduce us to countless people we had heard about but had never met. Soon we were settled in our college dormitory room, which brought back memories to us all. Later that evening we met up with other members of the ADCA contingent, along with other delegates from the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, S. -

A Guide to Dogs on the Farm

The magazine of modern homesteading & Small Stock Journal Volume 101 • Number 4 JULY/AUGUST 2017 PLUS: How to Use a Pressure Canner A Guide WELDING to Dogs on BASICS FOWL FALACIES EXPOSED the Farm BEE A GOOD NOTE TAKER Unique’s DC Solar Fridges Harnessts thehe sun -l- livivege grreeen!en! Unique’s nneeww solar powereddf fridge/ridge/freezers lead the wwayay in energy efficiencyyi inntn thehe DC rreefrigerfrigeration market. Designed ffoorro optimalptimal energy savings and easy, dependable use,U, Unique’nique’s ssolarolar refrigerators boasttt thehe woworld’rld’s lleadingeading DC cocomprmpressor (Secop/Danfoss), thick insulation throughout and LARGEST IN THETHE WORLD simple effortless controls. NEW! Unique 10 cu/ftDt DCCr refrigerefrigerator Unique 9c9 cu/fu/ftDt DCCr refrigerefrigerator Unique 16.6 cu/ftDt DCCr refrigerefrigerator UGP 290L1 B UGP 260L1 W UGP 470L1 Call us todayfor details andadealer near you! 1-877-427-2266 [email protected] www.UniqueOffGrid.com ©2017 Unique Off-Grid Appliances. All rights reserved. No power, no problem® is aregisteredtrademark of Unique Off-Grid Appliances. Never LoseElectricity Again! Ownthe #1 Brand in Home StandbyPower. 7out of 10 buyers choose Generac CALL TODAYfor Home Standby Generators to automatically provide electricity FREE Generator Guide, to their homes during power DVD, and Limited Time Offer. outages. GENERAC Home Standby Generators start at just $1,899.* *Price does not include installation. $695 BONUS OFFER! TOLL 017 FREE 877-200-6706 ©2 FreeGeneratorGuide.com 96758X I AM COUNTRYSIDE Show us what homesteading means to you! There are as many different reasons and ways to homestead as there are homesteaders today. -

Subchapter H—Animal Breeds

SUBCHAPTER HÐANIMAL BREEDS PART 151ÐRECOGNITION OF Book of record. A printed book or an BREEDS AND BOOKS OF RECORD approved microfilm record sponsored OF PUREBRED ANIMALS by a registry association and contain- ing breeding data relative to a large number of registered purebred animals DEFINITIONS used as a basis for the issuance of pedi- Sec. gree certificates. 151.1 Definitions. Certificates of pure breeding. A certifi- CERTIFICATION OF PUREBRED ANIMALS cate issued by the Administrator, for 151.2 Issuance of a certificate of pure breed- Bureau of Customs use only, certifying ing. that the animal to which the certifi- 151.3 Application for certificate of pure cate refers is a purebred animal of a breeding. recognized breed and duly registered in 151.4 Pedigree certificate. a book of record recognized under the 151.5 Alteration of pedigree certificate. regulations in this part for that breed. 151.6 Statement of owner, agent, or im- porter as to identity of animals. (a) The Act. Item 100.01 in part 1, 151.7 Examination of animal. schedule 1, of title I of the Tariff Act of 151.8 Eligibility of an animal for certifi- 1930, as amended (19 U.S.C. 1202, sched- cation. ule 1, part 1, item 100.01). Department. The United States De- RECOGNITION OF BREEDS AND BOOKS OF RECORD partment of Agriculture. Inspector. An inspector of APHIS or 151.9 Recognized breeds and books of record. 151.10 Recognition of additional breeds and of the Bureau of Customs of the United books of record. States Treasury Department author- 151.11 Form of books of record. -

Animal Genetic Resources Information Bulletin

The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Les appellations employées dans cette publication et la présentation des données qui y figurent n’impliquent de la part de l’Organisation des Nations Unies pour l’alimentation et l’agriculture aucune prise de position quant au statut juridique des pays, territoires, villes ou zones, ou de leurs autorités, ni quant au tracé de leurs frontières ou limites. Las denominaciones empleadas en esta publicación y la forma en que aparecen presentados los datos que contiene no implican de parte de la Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación juicio alguno sobre la condición jurídica de países, territorios, ciudades o zonas, o de sus autoridades, ni respecto de la delimitación de sus fronteras o límites. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and the extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Information Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy. Tous droits réservés. Aucune partie de cette publication ne peut être reproduite, mise en mémoire dans un système de recherche documentaire ni transmise sous quelque forme ou par quelque procédé que ce soit: électronique, mécanique, par photocopie ou autre, sans autorisation préalable du détenteur des droits d’auteur. -

Commission Decision of 26 August 2009 Amending Decision 2006/139

27.8.2009 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 224/15 COMMISSION DECISION of 26 August 2009 amending Decision 2006/139/EC as regards its period of applicability and the list of authorities in Canada approved for keeping a herdbook or register of certain animals (notified under document C(2009) 6522) (Text with EEA relevance) (2009/623/EC) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, (3) The entry for Bulgaria in the Annex to Decision 2006/139/EC became obsolete with the accession of Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European that Member State and should therefore be deleted for Community, the sake of legal clarity. (4) In addition, Canada has requested to update several Having regard to Council Directive 94/28/EC of 23 June 1994 entries for that country in the Annex to Decision laying down the principles relating to the zootechnical and 2006/139/EC. genealogical conditions applicable to imports from third countries of animals, their semen, ova and embryos, and (5) Canada has provided guarantees regarding compliance amending Directive 77/504/EEC on pure-bred breeding with the relevant requirements laid down in 1 animals of the bovine species ( ), and in particular Article 3 Community legislation and, in particular those laid thereof, down in Directive 94/28/EC. Whereas: (6) Decision 2006/139/EC should therefore be amended accordingly. (1) Commission Decision 2006/139/EC of 7 February 2006 implementing Council Directive 94/28/EC as regards a (7) The measures provided for in this Decision are in list of authorities in third countries approved for the accordance with the opinion of the Standing keeping of a herdbook or register of certain animals ( 2 ) Committee on Zootechnics, provides that Member States are to authorise the importation of breeding animals of certain species, their HAS ADOPTED THIS DECISION: semen, ova and embryos as ‘pure-bred’ or ‘hybrid’ only if they are entered or registered in a herdbook or register Article 1 kept by an authority approved for that purpose. -

GLAS SPECIFICATION for GLAS Tranche 2

DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND THE MARINE GLAS SPECIFICATION for GLAS Tranche 2 30th December 2015 Revised 17/9/2020 Eastát Chaisleáin Bhaile Sheáin, Co. Loch Garman, Y35 PN52 Johnstown Castle Estate, Co Wexford, Y35 PN52 T +353 53 9163400; Lo Call 0761 06 4415 www.gov.ie/agriculture Contents: Introduction 4 Abbreviations: 6 Actions: Minimum/ Maximum Units, Completion deadlines and Payment Rate 7 Arable Grass Margins 9 Bat Boxes 11 Bird Boxes 13 Conservation of Solitary Bees (Boxes) 15 Conservation of Solitary Bees (Sand) 17 Conservation of Farmland Birds 18 1. Breeding Wader and Curlew Specification 18 2. Chough 21 3. Corncrake 23 4. Geese and Swans 25 5. Grey Partridge 27 6. Hen Harrier 31 7. Twite (A, B and C) 35 Catch Crops 41 Commonage Management Plan (CMP) & Commonage Farm Plan (CFP) 44 Coppicing of Hedgerows 47 Environmental Management of Fallow Land 49 Farmland Habitat (Private Natura) 51 Laying of Hedgerows 53 Low Emission Slurry Spreading 55 Low Input Permanent Pasture 57 Minimum Tillage 60 Planting a Grove of Native Trees 61 Planting New Hedgerow 63 Protection and Maintenance of Archaeological Monuments 65 Protection of Watercourses from Bovines 69 Rare Breeds 72 Riparian Margins 75 Traditional Dry Stone Wall Maintenance 77 2 Traditional Hay Meadow 79 Traditional Orchards 81 Wild Bird Cover 83 Appendix 1a: Diagram for spiral out mowing for Corncrake Meadows 86 Appendix 1b: Grey Partridge eligible land areas 87 Appendix 1c: Twite eligible land areas. 88 Appendix 2: Interaction between Organic Farming Scheme (OFS) and GLAS 89 Appendix 3: Approved Native Hedgerow Species 90 Appendix 4: Native Irish trees for Planting a Grove of Native Trees 91 Appendix 5: Example Provenance Declaration Form for Planting of a Grove of Native Trees 93 Appendix 6: Campaign for Responsible Rodenticide Use Code (CRRU) 95 Appendix 8: Example of Bird box dimensions 97 Appendix 9: Example of Bee box dimensions 98 Appendix 11: Rare Breed Societies 100 Appendix 12: Activities Requiring Consent (ARC) List 102 Appendix 13: Information note for certain Natura site types. -

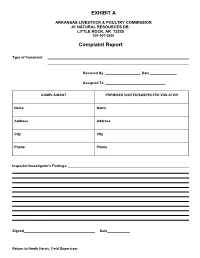

Complaint Report

EXHIBIT A ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK & POULTRY COMMISSION #1 NATURAL RESOURCES DR. LITTLE ROCK, AR 72205 501-907-2400 Complaint Report Type of Complaint Received By Date Assigned To COMPLAINANT PREMISES VISITED/SUSPECTED VIOLATOR Name Name Address Address City City Phone Phone Inspector/Investigator's Findings: Signed Date Return to Heath Harris, Field Supervisor DP-7/DP-46 SPECIAL MATERIALS & MARKETPLACE SAMPLE REPORT ARKANSAS STATE PLANT BOARD Pesticide Division #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 Insp. # Case # Lab # DATE: Sampled: Received: Reported: Sampled At Address GPS Coordinates: N W This block to be used for Marketplace Samples only Manufacturer Address City/State/Zip Brand Name: EPA Reg. #: EPA Est. #: Lot #: Container Type: # on Hand Wt./Size #Sampled Circle appropriate description: [Non-Slurry Liquid] [Slurry Liquid] [Dust] [Granular] [Other] Other Sample Soil Vegetation (describe) Description: (Place check in Water Clothing (describe) appropriate square) Use Dilution Other (describe) Formulation Dilution Rate as mixed Analysis Requested: (Use common pesticide name) Guarantee in Tank (if use dilution) Chain of Custody Date Received by (Received for Lab) Inspector Name Inspector (Print) Signature Check box if Dealer desires copy of completed analysis 9 ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK AND POULTRY COMMISSION #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 (501) 225-1598 REPORT ON FLEA MARKETS OR SALES CHECKED Poultry to be tested for pullorum typhoid are: exotic chickens, upland birds (chickens, pheasants, pea fowl, and backyard chickens). Must be identified with a leg band, wing band, or tattoo. Exemptions are those from a certified free NPIP flock or 90-day certificate test for pullorum typhoid. Water fowl need not test for pullorum typhoid unless they originate from out of state.