6 X 10.5 Three Line Title.P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Light on the Liao

A photo essay LIGHT ON THE LIAO n summer 2009, I was fortunate to participate in a summer seminar, ”China’s Northern Frontier,” co-sponsored I by the Silkroad Foundation, Yale University and Beijing University. Lecturers included some of the luminaries in the study of the Liao Dynasty and its history. In traveling through Gansu, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia and Lia- K(h)itan Abaoji in what is now Liaoning Province. At its peak, the Liao Empire controlled much of North China, Mongolia and territories far to the West. When it fell to the Jurchen in 1125, its remnants re-emerged as the Qara Khitai off in Central Asia, where they survived down to the creation of the Mongol empire (for their history, see the pioneering monograph by Michal Biran). While they began as semi-nomadic pastoralists, the Kitan/Liao in recent years from Liao tombs attest to their involvement in international trade and the sophistication of their cultural achievements. As with other states established in “borderlands” they drew on many different sources to create a distinctive culture which is now, after long neglect, being fully appreciated. These pictures touch but a few high points, leaving much else for separate exploration, which, it is hoped, they will stimulate readers to undertake on their own. The history and culture of the Kitan/Liao merit your serious attention, forming as they do an important chapter in the larger history of the silk roads. With the exception of the map and satellite image, the photos are all mine, a very few taken in collections outside of China, but the great majority during the seminar in 2009. -

The Khitans: Corner Stone of the Mongol Empire

ACTA VIA SERICA Vol. 6, No. 1, June 2021: 141–164 doi: 10.22679/avs.2021.6.1.006 The Khitans: Corner Stone of the Mongol Empire GEORGE LANE* The Khitans were a Turco-Mongol clan who dominated China north of the Yangtze River during the early mediaeval period. They adopted and then adapted many of the cultural traditions of their powerful neighbours to the south, the Song Chinese. However, before their absorption into the Mongol Empire in the late 13th century they proved pivotal, firstly in the eastward expansion of the armies of Chinggis Khan, secondly, in the survival of the Persian heartlands after the Mongol invasions of the 1220s and thirdly, in the revival and integration of the polity of Iran into the Chinggisid Empire. Da Liao, the Khitans, the Qara Khitai, names which have served this clan well, strengthened and invigorated the hosts which harboured them. The Liao willingly assimilated into the Chinggisid Empire of whose formation they had been an integral agent and in doing so they also surrendered their identity but not their history. Recent scholarship is now unearthing and recognising their proud legacy and distinct identity. Michal Biran placed the Khitans irrevocably and centrally in mediaeval Asian history and this study emphasises their role in the establishment of the Mongol Empire. Keywords: Khitans, Liao, Chinggids, Mongols, Ilkhanate * Dr. GEORGE LANE is a Research Associate at the School of History, Religion & Philosophy, SOAS University of London. 142 Acta Via Serica, Vol. 6, No. 1, June 2021 The Khitans: Corner Stone of the Mongol Empire The Turco-Mongol tribe that first settled the lands of northern China, north of the Huai River and adopted and adapted the cultural traditions of their domineering neighbour to the south, has only recently been acknowledged for their importance to the evolution of mediaeval Asian history, due in large part to the work of Michal Biran of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. -

The Mongols in Iran

chapter 10 THE MONGOLS IN IRAN george e. lane Iran was dramatically brought into the Mongol sphere of infl uence toward the end of the second decade of the thirteenth century. As well as the initial traumatic mili- tary incursions, Iran also experienced the start of prolonged martial rule, followed later by the domination and rule of the Mongol Ilkhans. However, what began as a brutal and vindictive invasion and occupation developed into a benign and cultur- ally and economically fl ourishing period of unity and strength. The Mongol period in Iranian history provokes controversy and debate to this day. From the horrors of the initial bloody irruptions, when the fi rst Mongol-led armies rampaged across northern Iran, to the glory days of the Ilkhanate-Yuan axis, when the Mongol- dominated Persian and Chinese courts dazzled the world, the Mongol infl uence on Iran of this turbulent period was profound. The Mongols not only affected Iran and southwestern Asia but they also had a devastating effect on eastern Asia, Europe, and even North Africa. In many parts of the world, the Middle East, Europe, and the Americas in particular, the Mongols’ name has since become synonymous with murder, massacre, and marauding may- hem. They became known as Tatars or Tartars in Europe and Western Asia for two reasons. Firstly, until Genghis Khan destroyed their dominance, the Tatars were the largest and most powerful of the Turco-Mongol tribes. And secondly, in Latin Tartarus meant hell and these tribes were believed to have issued from the depths of Hades. Their advent has been portrayed as a bloody “bolt from the blue” that left a trail of destruction, death, and horrifi ed grief in its wake. -

Pādshāh Khatun

chapter 14 Pādshāh Khatun An Example of Architectural, Religious, and Literary Patronage in Ilkhanid Iran bruno de nicola In comparison to sedentary societies, women in the Turkic-Mongol nomadic and seminomadic societies showed greater involvement in the political sphere, enjoyed a greater measure of financial autonomy, and generally had the freedom to choose their religious affiliations.1 Some women advanced to positions of immense power and wealth, even appointed as regent-empresses for the entire empire or regional khanates. Such examples included Töregene Khatun (r. 1242–46), Oghul Qaimish (r. 1248–50), and Orghina Khatun (r. 1251–59).2 Other women such as Qutui Khatun (d. 1284) in Mongol-ruled Iran accumulated great wealth from war booty, trade investment, and the allocation of tax revenues from the newly conquered territories.3 Through their unique prominence in the empire’s socio-economic system, elite women had an active role in financially supporting and protecting cultural and religious agents. Our understanding of the impact that Chinggisid women had on the flourishing of cultural life in the empire as a whole, and in the Ilkhanate of greater Iran in particular, remains poor, however. The historical record tells us little about the role that Chinggisid female members played as patrons of religious and cul- tural life, especially when comparted to the relative wealth of references to female influence in the political and economic arenas. However, abundant accounts show that female elite members from the local Turkic-Mongol dynasties who ruled as vassals for the Mongols, or had been incorporated into the ranks of the ruling Chinggisid household 270 Pādshāh Khatun | 271 through marriage, played a pivotal role as cultural and religious patrons. -

Inner Asian States and Empires: Theories and Synthesis

J Archaeol Res DOI 10.1007/s10814-011-9053-2 Inner Asian States and Empires: Theories and Synthesis J. Daniel Rogers Ó Springer Science+Business Media, LLC (outside the USA) 2011 Abstract By 200 B.C. a series of expansive polities emerged in Inner Asia that would dominate the history of this region and, at times, a very large portion of Eurasia for the next 2,000 years. The pastoralist polities originating in the steppes have typically been described in world history as ephemeral or derivative of the earlier sedentary agricultural states of China. These polities, however, emerged from local traditions of mobility, multiresource pastoralism, and distributed forms of hierarchy and administrative control that represent important alternative path- ways in the comparative study of early states and empires. The review of evidence from 15 polities illustrates long traditions of political and administrative organi- zation that derive from the steppe, with Bronze Age origins well before 200 B.C. Pastoralist economies from the steppe innovated new forms of political organization and were as capable as those based on agricultural production of supporting the development of complex societies. Keywords Empires Á States Á Inner Asia Á Pastoralism Introduction The early states and empires of Inner Asia played a pivotal role in Eurasian history, with legacies still evident today. Yet, in spite of more than 100 years of scholarly contributions, the region remains a relatively unknown heartland (Di Cosmo 1994; Hanks 2010; Lattimore 1940; Mackinder 1904). As pivotal as the history of Inner Asia is in its own right, it also holds special significance for how we interpret complex societies on a global basis. -

Climate in Medieval Central Eurasia

Climate in Medieval Central Eurasia Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Henry Misa Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2020 Thesis Committee Scott C. Levi, Advisor John L. Brooke 1 Copyrighted by Henry Ray Misa 2020 2 Abstract This thesis argues that the methodology of environmental history, specifically climate history, can help reinterpret the economic and political history of Central Eurasia. The introduction reviews the scholarly fields of Central Eurasian history, Environmental history and, in brief, Central Eurasian Environmental history. Section one introduces the methods of climate history and discusses the broad outlines of Central Eurasian climate in the late Holocene. Section two analyzes the rise of the Khitan and Tangut dynasties in their climatic contexts, demonstrating how they impacted Central Eurasia during this period. Section three discusses the sedentary empires of the Samanid and Ghaznavid dynasties in the context of the Medieval Climate Anomaly. Section four discusses the rise of the first Islamic Turkic empires during the late 10th and 11th century. Section five discusses the Qarakhitai and the Jurchen in the 12th century in the context of the transitional climate regime between the Medieval Quiet Period and the early Little Ice Age. The conclusion summarizes the main findings and their implications for the study of Central Eurasian Climate History. This thesis discusses both long-term and short-term time scales; in many cases small-scale political changes and complexities impacted how the long-term patterns of climate change impacted regional economies. -

Political Order in Pre-Modern Eurasia: Imperial Incorporation and the Hereditary Divisional System

Political Order in Pre-Modern Eurasia: Imperial Incorporation and the Hereditary Divisional System LHAMSUREN MUNKH-ERDENE1 Abstract Comparing the Liao, the Chinggisid and the Qing successive incorporations of Inner Asia, this article is prepared to argue that the hereditary divisional system that these Inner Asian empires employed to incorporate and administer their nomadic population was the engine that generated what scholars see either as ‘tribes’ or ‘aristocratic order’. This divisional system, because of its hereditary membership and rulership, invariably tended to produce autonomous lordships with distinct names and identities unless the central government took measures to curb the tendency. Whenever the central power waned, these divisions emerged as independent powers in themselves and their lords as contenders for the central power. The Chinggisid power structure did not destroy any tribal order; instead, it destroyed and incorporated a variety of former Liao politico-administrative divisions into its own decimally organized minqans and transformed the former Liao divisions into quasi-political named categories of populace, the irgens, stripping them of their own politico-administrative structures. In turn, the Qing, in incorporating Mongolia, divided the remains of the Chinggisid divisions, the tumens¨ and otogs,intokhoshuu and transformed them into quasi-political ayimaqs. Thus, it was the logic of the imperial incorporation and the hereditary divisional system that produced multiple politico-administrative divisions and quasi- political identity categories. Introduction Although many scholars consider the emergence of the Chinggisid power structure to have been a watershed in Eurasian political and social transformation because it appeared to have replaced the region’s ‘tribal’ order with a highly centralised state, some still regard it as a ‘supercomplex chiefdom’.2 Indeed, with the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Eurasia 1Lhamsuren Munkh-Erdene is currently a Humboldt Research Fellow at Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology. -

Download Article

AJA ONLINE PUBLICATIONS: MUSEUM REVIEW GILDED TREASURES OF A LOST EMPIRE BY VICTOR CUNRUI XIONG GILDED SPLENDOR: TREASURES OF area (present-day Xar Moron Valley, east Inner CHINA’S LIAO EMPIRE (907–1125), ASIA Mongolia).1 The Qidan became much more SOCIETY AND MUSEUM, NEW YORK, visible in history during the Tang dynasty 5 OCTOBER–31 DECEMBER 2006, orga- (618–907). One of the most meritorious Tang nized by Hsueh-man Shen, Adriana Proser, generals of the post–An Lushan rebellion era, and John H. Foster. Li Guangbi (708–764), was of Qidan descent, as was the military commissioner Wang Wujun GILDED SPLENDOR: TREASURES OF CHI- (735–801). Composed of eight tribes, the Qidan NA’S LIAO EMPIRE (907–1125), edited by had become a powerful tribal confederation by Hsueh-man Shen. Pp. 391, fi gs. 121. Asia Soci- 907, capturing territory in Manchuria and Mon- ety, New York 2006. $75. ISBN 8874393326. golia by way of conquest. At their head was Yelü Aboaji, who made himself a Chinese-style In the early 10th century, the Qidan ex- emperor in 916, having physically eliminated ploded onto the scene to build and success- his political rivals (the tribal chieftains who fully shape their extensive Qidan-Liao empire had been responsible for electing confedera- into the preeminent power in east Asia. About tion leaders).2 two centuries later, they became a subjugated In the chaotic subsequent era of the Five people as their empire crumbled. Under the Dynasties (907–979), Qidan was beyond doubt rule of the Jurchens, their written language the most formidable power in the Chinese went into oblivion. -

Shishi: a Stone Structure Associated with Abaoji in Zuzhou

stone structure in zuzhou nancy shatzman steinhardt Shishi: A Stone Structure Associated with Abaoji in Zuzhou t is hard to argue that the primary meaning of the first shi in the two- is anything but “stone.” The typeف I character combination shishi of stone is not specified in dictionary or encyclopedia definitions, but that the material is hard and permanent, is.1 The second shi is less ob- vious to translate. A primary meaning and frequent translation is room, or chamber, but there are other possibilities.2 Shishi is used in modern Chinese studies to name one of the most enigmatic structures in East Asia (figure 1, overleaf). Situated in Chi- feng ߧ county of Inner Mongolia, this building has been called shi- shi at least since the twentieth century.3 In 1922, Father Joseph Mullie referred to it as “la Maison de Pierre,” or Stone House, following, he wrote, the Mongolian name used by the local population.4 (In the pres- ent article, the capitalized words “Shishi” and “Stone House” are used to designate this specific stone structure in Inner Mongolia.) Mullie’s sketch of the outer walled area that confined la Maison de Pierre was remarkably accurate (figure 2). Except for battlements that project on three of its sides, one finds little difference between Mullie’s wall with five, simple straight segments and the plan pub- lished sixty-nine years later by the Chinese researchers who engaged The first version of this paper was presented at a conference at the University of Pennsyl- vania in December 2003 in honor of the sixtieth birthday of Victor H. -

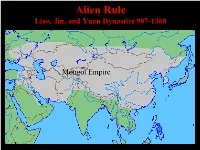

Alien Rule Liao, Jin, and Yuan Dynasties 907-1368

Alien Rule Liao, Jin, and Yuan Dynasties 907-1368 Alien Rule The Song dynasty defeated by the Mongols in 1276. Alien Rule Mongolian Steppe Alien Rule Khitan were the first major nomadic tribe with which China had to deal. Abaoji created the Liao dynasty. The Jurchens lead by Aguda founded the Jin dynasty, ousted the Khitans and then went after the Song dynasty. Chinggis Khan unites the Mongol tribes, and then he goes off to conquer the world. Alien Rule Expansion of Liao Dynasty 907 to 960 Alien Rule Examples of Mongol warriors Alien Rule Chinggis Khan (ca. 1162-1227) was extremely aggressive in making war with massive areas surrounding Mongolia. You would be given an option to be with him or else…. It is estimated that nearly 20 million Asian share Chinggis’ Y-chromosome pattern because of his alleged policy of impregnating of conquered women. Two interviews with people looking for Chinggis Khan’s burial site: •http://www.wolverton- mountain.com/interviews/people/woods.htm •http://www.wolverton- mountain.com/interviews/people/maury__kratvitz.htm Chinggis Khan Alien Rule Khubilai named his dynasty, Yuan. He succeeded in conquering the Song dynasty with the help of a massive river siege. Khubilai Khan Alien Rule Life in China Under Alien Rule • Mongols didn’t force a new culture on the Chinese. It was a laissez faire attitude paralleling the way the north dealt with new ideas. • However, life for the ordinary peasant was often harsh—especially taxes. • Massive inflation resulted. • On the brighter side, the Mongols reunited the north and south. • The Mongol societal caste system was very elaborate with each level treated differently than the ones above or below. -

The Qarakhanids' Eastern Exchange: Preliminary Notes on the Silk Roads

THE QARAKHANIDS’ EASTERN EXCHANGE: PRELIMINARY NOTES ON THE SILK ROADS IN THE ELEVENTH AND TWELFTH CENTURIES Michal Biran Despite the recent spike in Silk Road research, the period from the tenth to the twelfth century is often overlooked. Even recent studies, such as Liu Xinru’s “The Silk Road in World History” (2010, 110–111) or Christopher Beckwith’s voluminous “Empires of the Silk Roads” (2008, 165– 175) dedicate only a few pages to this timespan1. Squeezed in between the halcyon days of the Tang-Abbasid exchange and Mongol dominion, encumbered by political fragmentation, and sorely lacking in documentation, the years between the tenth and twelfth centuries indeed con- stitute one of the most neglected periods in the history of the Silk Roads. Common wisdom holds that the collapse of the Tang dynasty in 907, the weakening of the Abbasid Caliphate from the ninth century on, and the downfall of the Uyghur confederation in the mid-800s disrupted trade across the continental Silk Roads. With the land routes largely cut off by hostile states to the north, China re-oriented its foreign commerce to the sea. Maritime trade with Japan, Southeast Asia, and the Indian Ocean basin prospered throughout the Song period. In the process, the ports of Guangzhou and Quanzhou on China’s southern coast became home to large communities of Arab, Persian, Malay, and Tamil traders (von Glahn forthcoming). While the vim of the maritime routes is certainly well-documented, I argue that overland trade and cross-cultural exchanges not only endured throughout this period, but were substan- tial in their own right. -

Nomads and Settlement: New Perspectives in the Archaeology of Mongolia, by Daniel C

ISSN 2152-7237 (print) ISSN 2153-2060 (online) The Silk Road Volume 8 2010 Contents From the Editor’s Desktop ................................................................... 3 Images from Ancient Iran: Selected Treasures from the National Museum in Tehran. A Photographic Essay ............................................................... 4 Ancient Uighur Mausolea Discovered in Mongolia, by Ayudai Ochir, Tserendorj Odbaatar, Batsuuri Ankhbayar and Lhagwasüren Erdenebold .......................................................................................... 16 The Hydraulic Systems in Turfan (Xinjiang), by Arnaud Bertrand ................................................................................. 27 New Evidence about Composite Bows and Their Arrows in Inner Asia, by Michaela R. Reisinger .......................................................................... 42 An Experiment in Studying the Felt Carpet from Noyon uul by the Method of Polypolarization, by V. E. Kulikov, E. Iu. Mednikova, Iu. I. Elikhina and Sergei S. Miniaev .................... 63 The Old Curiosity Shop in Khotan, by Daniel C. Waugh and Ursula Sims-Williams ................................................. 69 Nomads and Settlement: New Perspectives in the Archaeology of Mongolia, by Daniel C. Waugh ................................................................................ 97 (continued) “The Bridge between Eastern and Western Cultures” Book notices (except as noted, by Daniel C. Waugh) The University of Bonn’s Contributions to Asian Archaeology