Integration and Separation: the Framing of the Liao Dynasty (907–1125) in Chinese Sources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imagining a Universal Empire: a Study of the Illustrations of the Tributary States of the Myriad Regions Attributed to Li Gonglin

Journal of chinese humanities 5 (2019) 124-148 brill.com/joch Imagining a Universal Empire: a Study of the Illustrations of the Tributary States of the Myriad Regions Attributed to Li Gonglin Ge Zhaoguang 葛兆光 Professor of History, Fudan University, China [email protected] Abstract This article is not concerned with the history of aesthetics but, rather, is an exercise in intellectual history. “Illustrations of Tributary States” [Zhigong tu 職貢圖] as a type of art reveals a Chinese tradition of artistic representations of foreign emissaries paying tribute at the imperial court. This tradition is usually seen as going back to the “Illustrations of Tributary States,” painted by Emperor Yuan in the Liang dynasty 梁元帝 [r. 552-554] in the first half of the sixth century. This series of paintings not only had a lasting influence on aesthetic history but also gave rise to a highly distinctive intellectual tradition in the development of Chinese thought: images of foreign emis- saries were used to convey the Celestial Empire’s sense of pride and self-confidence, with representations of strange customs from foreign countries serving as a foil for the image of China as a radiant universal empire at the center of the world. The tra- dition of “Illustrations of Tributary States” was still very much alive during the time of the Song dynasty [960-1279], when China had to compete with equally powerful neighboring states, the empire’s territory had been significantly diminished, and the Chinese population had become ethnically more homogeneous. In this article, the “Illustrations of the Tributary States of the Myriad Regions” [Wanfang zhigong tu 萬方職貢圖] attributed to Li Gonglin 李公麟 [ca. -

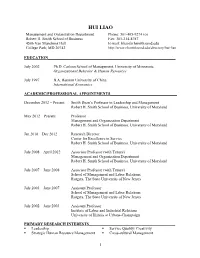

HUI LIAO Management and Organization Department Phone: 301-405-9274 (O) Robert H

HUI LIAO Management and Organization Department Phone: 301-405-9274 (o) Robert H. Smith School of Business Fax: 301-214-8787 4506 Van Munching Hall E-mail: [email protected] College Park, MD 20742 http://www.rhsmith.umd.edu/directory/hui-liao EDUCATION_________________________________________________________________ July 2002 Ph.D. Carlson School of Management, University of Minnesota Organizational Behavior & Human Resources July 1997 B.A. Renmin University of China International Economics ACADEMIC/PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS__________________________________ December 2012 – Present Smith Dean’s Professor in Leadership and Management Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland May 2012 – Present Professor Management and Organization Department Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland Jan 2010 – Dec 2012 Research Director Center for Excellence in Service Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland July 2008 – April 2012 Associate Professor (with Tenure) Management and Organization Department Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland July 2007 – June 2008 Associate Professor (with Tenure) School of Management and Labor Relations Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey July 2003 – June 2007 Assistant Professor School of Management and Labor Relations Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey July 2002 – June 2003 Assistant Professor Institute of Labor and Industrial Relations University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign PRIMARY RESEARCH INTERESTS____________________________________________ . Leadership . Service Quality/ Creativity . Strategic Human Resource Management . Cross-cultural Management 1 MAJOR SCHOLARLY AWARDS AND HONORS__________________________________ . 2012, Named an endowed professorship – Smith Dean’s Professor in Leadership and Management, Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland . 2012, Cummings Scholarly Achievement Award, OB Division, Academy of Management . -

Of Ouyang Xiu's Literary Work: from the Perspective of Emotion

The "World" of Ouyang Xiu's Literary Work: From the Perspective of Emotion By: Seong Lin Ding (Paper presented at the 4th International Conference of Literary Communication and Literary Reception held on 25-29 March 2010 in Hualien, Taiwan) The "World" of Ouyang Xiu's Literary Work: From the Perspective of Emotion Seong Lin Ding University of Malaya There are numerous researches on the biography of Ouyang Xiu; however the focus on his inner emotion is scarce. In my point of view, this aspect is actually the focal point of his life and is strongly reflected in most of his writings; from his memory of mentors and friends, his remembrance on the places visited, his writing on history, to his collections of ancient bronzes and stone tablets, his emotion is always the crucial part of his reflection and value judgment. This emotional state evolved continuously at his different period of life and different stages of writings. It was undoubtedly affected by his maturity in age and life experience but his physical, psychological and temperament conditions are the more prominent affecting factors. As a result, we can find a gap between the "Ouyang Xiu" shown in the biography and Chinese literary history compared with the "Ouyang Xiu" enshrined in his literary work. This might due to the objectivity underlined in biography and the emotional subjectivity underlined in literary works. More interestingly, the former is about reality of life and the latter is about "world" of literary works, which is not an objective reality, but was actually organized and experienced by an individual subject. -

Historiography and Narratives of the Later Tang (923-936) and Later Jin (936-947) Dynasties in Tenth- to Eleventh- Century Sources

Historiography and Narratives of the Later Tang (923-936) and Later Jin (936-947) Dynasties in Tenth- to Eleventh- century Sources Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie an der Ludwig‐Maximilians‐Universität München vorgelegt von Maddalena Barenghi Aus Mailand 2014 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Hans van Ess Zweitgutachter: Prof. Tiziana Lippiello Datum der mündlichen Prüfung: 31.03.2014 ABSTRACT Historiography and Narratives of the Later Tang (923-36) and Later Jin (936-47) Dynasties in Tenth- to Eleventh-century Sources Maddalena Barenghi This thesis deals with historical narratives of two of the Northern regimes of the tenth-century Five Dynasties period. By focusing on the history writing project commissioned by the Later Tang (923-936) court, it first aims at questioning how early-tenth-century contemporaries narrated some of the major events as they unfolded after the fall of the Tang (618-907). Second, it shows how both late- tenth-century historiographical agencies and eleventh-century historians perceived and enhanced these historical narratives. Through an analysis of selected cases the thesis attempts to show how, using the same source material, later historians enhanced early-tenth-century narratives in order to tell different stories. The five cases examined offer fertile ground for inquiry into how the different sources dealt with narratives on the rise and fall of the Shatuo Later Tang and Later Jin (936- 947). It will be argued that divergent narrative details are employed both to depict in different ways the characters involved and to establish hierarchies among the historical agents. Table of Contents List of Rulers ............................................................................................................ ii Aknowledgements .................................................................................................. -

Spotlight and Hot Topic Sessions Poster Sessions Continuing

Sessions and Events Day Thursday, January 21 (Sessions 1001 - 1025, 1467) Friday, January 22 (Sessions 1026 - 1049) Monday, January 25 (Sessions 1050 - 1061, 1063 - 1141) Wednesday, January 27 (Sessions 1062, 1171, 1255 - 1339) Tuesday, January 26 (Sessions 1142 - 1170, 1172 - 1254) Thursday, January 28 (Sessions 1340 - 1419) Friday, January 29 (Sessions 1420 - 1466) Spotlight and Hot Topic Sessions More than 50 sessions and workshops will focus on the spotlight theme for the 2019 Annual Meeting: Transportation for a Smart, Sustainable, and Equitable Future . In addition, more than 170 sessions and workshops will look at one or more of the following hot topics identified by the TRB Executive Committee: Transformational Technologies: New technologies that have the potential to transform transportation as we know it. Resilience and Sustainability: How transportation agencies operate and manage systems that are economically stable, equitable to all users, and operated safely and securely during daily and disruptive events. Transportation and Public Health: Effects that transportation can have on public health by reducing transportation related casualties, providing easy access to healthcare services, mitigating environmental impacts, and reducing the transmission of communicable diseases. To find sessions on these topics, look for the Spotlight icon and the Hot Topic icon i n the “Sessions, Events, and Meetings” section beginning on page 37. Poster Sessions Convention Center, Lower Level, Hall A (new location this year) Poster Sessions provide an opportunity to interact with authors in a more personal setting than the conventional lecture. The papers presented in these sessions meet the same review criteria as lectern session presentations. For a complete list of poster sessions, see the “Sessions, Events, and Meetings” section, beginning on page 37. -

Commissioner Li and Prefect Huang: Sino-Vietnamese Frontier Trade Networks and Political Alliances in the Southern Song

sino-vietnamese trade and alliances james a. anderson Commissioner Li and Prefect Huang: Sino-Vietnamese Frontier Trade Networks and Political Alliances in the Southern Song INTRODUCTION rom the 900s to the 1200s, political loyalties in the upland areas F along the Sino-Vietnamese frontier were a complicated matter. The Dai Viet 大越 kingdom, while adopting elements of the imperial Chinese system of frontier administration, ruled at less of a distance from their upland subjects. Marriage alliances between the local elite and the Ly 李 (1009–1225) and Tran 陳 (1225–1400) royal dynasties helped bind these upland areas more closely to the central court. By contrast, both the Northern and Southern Song courts (960–1279) were preoccupied with their northern frontiers, investing most of the courts’ resources in that region, while relying on a small contingent of officials situated in Yongzhou 邕州 (modern-day Nanning) to pursue imperial aims along the southern frontier. The behavior of the frontier elite was also closely linked to changes in the flow of trade across the Sino-Vietnamese bor- derlands, and the impact of changing patterns in trade will play a role in this study. Broadly speaking, this paper focuses on a triangular re- gion, the base of which stretches from the Song port of Qinzhou 欽州 to the inland frontier region at Longzhou 龍州 (Guangxi). (See the maps provided in the Introduction to this volume.) These two points at either end of the base in this territorial triangle meet at Yongzhou, which was the center of early-Song administration for the Guangnan West circuit (Guangnan xilu 廣南西路). -

The Eurasian Transformation of the 10Th to 13Th Centuries: the View from Song China, 906-1279

Haverford College Haverford Scholarship Faculty Publications History 2004 The Eurasian Transformation of the 10th to 13th centuries: The View from Song China, 906-1279 Paul Jakov Smith Haverford College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.haverford.edu/history_facpubs Repository Citation Smith, Paul Jakov. “The Eurasian Transformation of the 10th to 13th centuries: The View from the Song.” In Johann Arneson and Bjorn Wittrock, eds., “Eurasian transformations, tenth to thirteenth centuries: Crystallizations, divergences, renaissances,” a special edition of the journal Medieval Encounters (December 2004). This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Haverford Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Haverford Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Medieval 10,1-3_f12_279-308 11/4/04 2:47 PM Page 279 EURASIAN TRANSFORMATIONS OF THE TENTH TO THIRTEENTH CENTURIES: THE VIEW FROM SONG CHINA, 960-1279 PAUL JAKOV SMITH ABSTRACT This essay addresses the nature of the medieval transformation of Eurasia from the perspective of China during the Song dynasty (960-1279). Out of the many facets of the wholesale metamorphosis of Chinese society that characterized this era, I focus on the development of an increasingly bureaucratic and autocratic state, the emergence of a semi-autonomous local elite, and the impact on both trends of the rise of the great steppe empires that encircled and, under the Mongols ultimately extinguished the Song. The rapid evolution of Inner Asian state formation in the tenth through the thirteenth centuries not only swayed the development of the Chinese state, by putting questions of war and peace at the forefront of the court’s attention; it also influenced the evolution of China’s socio-political elite, by shap- ing the context within which elite families forged their sense of coorporate identity and calibrated their commitment to the court. -

A Dynamic Schedule Based on Integrated Time Performance Prediction

2009 First International Conference on Information Science and Engineering (ICISE 2009) Nanjing, China 26 – 28 December 2009 Pages 1-906 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP0976H-PRT ISBN: 978-1-4244-4909-5 1/6 TABLE OF CONTENTS TRACK 01: HIGH-PERFORMANCE AND PARALLEL COMPUTING A DYNAMIC SCHEDULE BASED ON INTEGRATED TIME PERFORMANCE PREDICTION ......................................................1 Wei Zhou, Jing He, Shaolin Liu, Xien Wang A FORMAL METHOD OF VOLUNTEER COMPUTING .........................................................................................................................5 Yu Wang, Zhijian Wang, Fanfan Zhou A GRID ENVIRONMENT BASED SATELLITE IMAGES PROCESSING.............................................................................................9 X. Zhang, S. Chen, J. Fan, X. Wei A LANGUAGE OF NEUTRAL MODELING COMMAND FOR SYNCHRONIZED COLLABORATIVE DESIGN AMONG HETEROGENEOUS CAD SYSTEMS ........................................................................................................................12 Wanfeng Dou, Xiaodong Song, Xiaoyong Zhang A LOW-ENERGY SET-ASSOCIATIVE I-CACHE DESIGN WITH LAST ACCESSED WAY BASED REPLACEMENT AND PREDICTING ACCESS POLICY.......................................................................................................................16 Zhengxing Li, Quansheng Yang A MEASUREMENT MODEL OF REUSABILITY FOR EVALUATING COMPONENT...................................................................20 Shuoben Bi, Xueshi Dong, Shengjun Xue A M-RSVP RESOURCE SCHEDULING MECHANISM IN PPVOD -

Kaiming Press and the Cultural Transformation of Republican China

PRINTING, READING, AND REVOLUTION: KAIMING PRESS AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF REPUBLICAN CHINA BY LING A. SHIAO B.A., HEFEI UNITED COLLEGE, 1988 M.A., PENNSYVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY, 1993 M.A., BROWN UNIVERSITY, 1996 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AT BROWN UNIVERSITY PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2009 UMI Number: 3370118 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform 3370118 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 © Copyright 2009 by Ling A. Shiao This dissertation by Ling A. Shiao is accepted in its present form by the Department of History as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date W iO /L&O^ Jerome a I Grieder, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date ^)u**u/ef<2coy' Richard L. Davis, Reader DateOtA^UT^b Approved by the Graduate Council Date w& Sheila Bonde, Dean of the Graduate School in Ling A. -

The Road to Literary Culture: Revisiting the Jurchen Language Examination System*

T’OUNG PAO 130 T’oung PaoXin 101-1-3 Wen (2015) 130-167 www.brill.com/tpao The Road to Literary Culture: Revisiting the Jurchen Language Examination System* Xin Wen (Harvard University) Abstract This essay contextualizes the unique institution of the Jurchen language examination system in the creation of a new literary culture in the Jin dynasty (1115–1234). Unlike the civil examinations in Chinese, which rested on a well-established classical canon, the Jurchen language examinations developed in close connection with the establishment of a Jurchen school system and the formation of a literary canon in the Jurchen language and scripts. In addition to being an official selection mechanism, the Jurchen examinations were more importantly part of a literary endeavor toward a cultural ideal. Through complementing transmitted Chinese sources with epigraphic sources in Jurchen, this essay questions the conventional view of this institution as a “Jurchenization” measure, and proposes that what the Jurchen emperors and officials envisioned was a road leading not to Jurchenization, but to a distinctively hybrid literary culture. Résumé Cet article replace l’institution unique des examens en langue Jurchen dans le contexte de la création d’une nouvelle culture littéraire sous la dynastie des Jin (1115–1234). Contrairement aux examens civils en chinois, qui s’appuyaient sur un canon classique bien établi, les examens en Jurchen se sont développés en rapport étroit avec la mise en place d’un système d’écoles Jurchen et avec la formation d’un canon littéraire en langue et en écriture Jurchen. En plus de servir à la sélection des fonctionnaires, et de façon plus importante, les examens en Jurchen s’inscrivaient * This article originated from Professor Peter Bol’s seminar at Harvard University. -

Mongols, Turks, and Others Brill’S Inner Asian Library

MONGOLS, TURKS, AND OTHERS BRILL’S INNER ASIAN LIBRARY edited by NICOLA DI COSMO DEVIN DEWEESE CAROLINE HUMPHREY VOLUME 11 MONGOLS, TURKS, AND OTHERS Eurasian Nomads and the Sedentary World EDITED BY REUVEN AMITAI AND MICHAL BIRAN BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2005 On the cover: Mongol horsemen in combat, from RashÊd al-DÊn’s J§mi" al-taw§rÊkh, MS Supp. Persan 1113, fol. 231v. © Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mongols, Turks, and others : Eurasian nomads and the sedentary world / edited by Reuven Amitai and Michal Biran. p. cm. — (Brill’s Inner Asian library ; vol. 11) Includes bibliographical references and index ISBN 90-04-14096-4 1. Mongols—History. 2. Turkic peoples—History. 3. Eurasia—History. I. Title : Eurasian nomads and the sedentary world. II. Amitai, Reuven. III. Biran, Michal. IV. Series. DS19.M648 2004 950’.04942—dc22 2004054503 ISSN 1566-7162 ISBN 90 04 14096 4 © Copyright 2005 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Academic Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. -

Histoire De L'extrême-Orient Prémoderne Et Épigraphie Chinoise

Annuaire de l'École pratique des hautes études (EPHE), Section des sciences historiques et philologiques Résumés des conférences et travaux 141 | 2011 2008-2009 Histoire de l’Extrême-orient prémoderne et épigraphie chinoise Pierre Marsone Édition électronique URL : https://journals.openedition.org/ashp/1063 DOI : 10.4000/ashp.1063 ISSN : 1969-6310 Éditeur Publications de l’École Pratique des Hautes Études Édition imprimée Date de publication : 2 février 2011 Pagination : 341-347 ISSN : 0766-0677 Référence électronique Pierre Marsone, « Histoire de l’Extrême-orient prémoderne et épigraphie chinoise », Annuaire de l'École pratique des hautes études (EPHE), Section des sciences historiques et philologiques [En ligne], 141 | 2011, mis en ligne le 25 février 2011, consulté le 06 juillet 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ashp/ 1063 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ashp.1063 Tous droits réservés : EPHE Résumés des conférences 341 HISTOIRE DE L’EXTRÊME-ORIENT PRÉMODERNE ET ÉPIGRAPHIE CHINOISE Maître de conférences : M. Pierre Marsone Programme de l’année 2008-2009 : I. Histoire des empires sinisés (Liao, Jin) et de la Chine sous les Mongols : textes historiques sur l’installation et la consolidation de l’empire des Khitan (IX e siècle). — II. Initiation à l’épigraphie chinoise : stèles de personnages mongols et d’Asie centrale sous les Yuan (suite). I. Fondation de l’empire khitan : la deuxième partie du règne d’Abaoji (916-926) Dans le cadre du programme historique des conférences, nous avons étudié en détail la deuxième partie du règne d’Abaoji (916-926) à travers une lecture intégrale, annotée et commentée, du deuxième chapitre de l’Histoire des Liao (Liaoshi).