Bullets and Badges: Understanding the Relationships Between Cultural Commodities and Identity Formation in an Era of Gaza Vs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Vybz Kartel Kingston Story Album Free.Zip Download Vybz Kartel Kingston Story Album Free.Zip

download vybz kartel kingston story album free.zip Download vybz kartel kingston story album free.zip. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 66aecbef9fd1c401 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Kingston Story. As titles go, Kingston Story is merely a case of key track graduating to title track because this slow-rolling and electro-flavored album qualifies as Vybz Kartel's least "Jamaican" release to date, including his collaboration with Major Lazer. Recorded with Mixpak Records owner and tasty house music producer Dre Skull, enjoyment of the album relies on adjusting expectations as Skull's beats aren't the usual clever and Kartel's performance is at half-speed, a pace that causes him to crack less jokes and reflect more, even if heavy issues like jail time and arrests are not what Vybz cares to address right here. In fact, "My Crew" is lightweight stuff lyrically, with Vybz toasting champagne and rattling off porno video titles at a Southern, syrup-sipping, hip-hop pace, but it's also a highlight as Skull bangs the timpani and drops quirky bits of Vybz in full ecstasy. -

EINZELHANDEL NEUHEITEN-KATALOG NR. 129 RINSCHEWEG 26 IRIE RECORDS GMBH (CD/LP/10" & 12"/7"/Dvds/Books) D-48159 MÜNSTER KONTO NR

IRIE RECORDS GMBH IRIE RECORDS GMBH BANKVERBINDUNGEN: EINZELHANDEL NEUHEITEN-KATALOG NR. 129 RINSCHEWEG 26 IRIE RECORDS GMBH (CD/LP/10" & 12"/7"/DVDs/Books) D-48159 MÜNSTER KONTO NR. 31360-469, BLZ 440 100 46 (VOM 27.07.2003 BIS 08.08.2003) GERMANY POSTBANK NL DORTMUND TEL. 0251-45106 KONTO NR. 35 60 55, BLZ 400 501 50 SCHUTZGEBÜHR: 0,50 EUR (+ PORTO) FAX. 0251-42675 SPARKASSE MÜNSTERLAND OST EMAIL: [email protected] HOMEPAGE: www.irie-records.de GESCHÄFTSFÜHRER: K.E. WEISS/SITZ: MÜNSTER/HRB 3638 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ IRIE RECORDS GMBH: DISTRIBUTION - WHOLESALE - RETAIL - MAIL ORDER - SHOP - YOUR SPECIALIST IN REGGAE & SKA -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- GESCHÄFTSZEITEN: MONTAG/DIENSTAG/MITTWOCH/DONNERSTAG/FREITAG 13 – 19 UHR; SAMSTAG 12 – 16 UHR ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ *** CDs *** ALPHA BLONDY...................... PARIS BERCY................... EMI............ (FRA) (00/01). 19.99EUR GLADSTONE ANDERSON & THE MUDIE ALL STARS........................ GLADY UNLIMITED............... MOODISC........ (USA) (77/99). 21.99EUR HORACE ANDY....................... FEEL GOOD ALL OVER: ANTHOLOGY. TROJAN......... (USA) (--/02). 21.99EUR 2CD BADAWI............................ SOLDIER OF MIDIAN............. ROIR........... (USA) (01/01). 21.99EUR BEENIE MAN/BUJU BANTON/BOUNTY KILLER.......................... -

Dancehall Dossier.Cdr

DANCEHALL DOSSIER STOP M URDER MUSIC DANCEHALL DOSSIER Beenie Man Beenie Man - Han Up Deh Hang chi chi gal wid a long piece of rope Hang lesbians with a long piece of rope Beenie Man Damn I'm dreaming of a new Jamaica, come to execute all the gays I'm dreaming of a new Jamaica, come to execute all the gays Beenie Man Beenie Man - Batty Man Fi Dead Real Name: Anthony M Davis (aka ‘Weh U No Fi Do’) Date of Birth: 22 August 1973 (Queers Must Be killed) All batty man fi dead! Jamaican dancehall-reggae star Beenie All faggots must be killed! Man has personally denied he had ever From you fuck batty den a coppa and lead apologised for his “kill gays” music and, to If you fuck arse, then you get copper and lead [bullets] prove it, performed songs inciting the murder of lesbian and gay people. Nuh man nuh fi have a another man in a him bed. No man must have another man in his bed In two separate articles, The Jamaica Observer newspaper revealed Beenie Man's disavowal of his apology at the Red Beenie Man - Roll Deep Stripe Summer Sizzle concert at James Roll deep motherfucka, kill pussy-sucker Bond Beach, Jamaica, on Sunday 22 August 2004. Roll deep motherfucker, kill pussy-sucker Pussy-sucker:a lesbian, or anyone who performs cunnilingus. “Beenie Man, who was celebrating his Tek a Bazooka and kill batty-fucker birthday, took time to point out that he did not apologise for his gay-bashing lyrics, Take a bazooka and kill bum-fuckers [gay men] and went on to perform some of his anti- gay tunes before delving into his popular hits,” wrote the Jamaica Observer QUICK FACTS “He delivered an explosive set during which he performed some of the singles that have drawn the ire of the international Virgin Records issued an apology on behalf Beenie Man but within gay community,” said the Observer. -

United Reggae Magazine #7

MAGAZINE #14 - December 2011 INTERVIEW Ken Boothe Derajah Susan Cadogan I-Taweh Dax Lion King Spinna Records Tribute to Fattis Burrell - One Love Sound Festival - Jamaica Round Up C-Sharp Album Launch - Frankie Paul and Cocoa Tea in Paris King Jammy’s Dynasty - Reggae Grammy 2012 United Reggae Magazine #14 - December 2011 Want to read United Reggae as a paper magazine? Now you can... In addition to the latest United Reggae news, views and videos online each month you can now enjoy a SUMMARY free pdf version packed with most of United Reggae content from the last month. 1/ NEWS EDITORIAL by Erik Magni 2/ INTERVIEWS • Bob Harding from King Spinna Records 10 • I-Taweh 13 • Derajah 18 • Ken Boothe 22 • Dax Lion 24 • Susan Cadogan 26 3/ REVIEWS • Derajah - Paris Is Burning 29 • Dub Vision - Counter Attack 30 • Dial M For Murder - In Dub Style 31 • Gregory Isaacs - African Museum + Tads Collection Volume II 32 • The Album Cover Art of Studio One Records 33 Reggae lives on • Ashley - Land Of Dub 34 • Jimmy Cliff - Sacred Fire 35 • Return of the Rub-A-Dub Style 36 This year it has been five years since the inception of United Reggae. Our aim • Boom One Sound System - Japanese Translations In Dub 37 in 2007 was to promote reggae music and reggae culture. And this still stands. 4/ REPORTS During this period lots of things have happened – both in the world of reg- • Jamaica Round Up: November 2011 38 gae music and for United Reggae. Today United Reggae is one of the leading • C-Sharp Album Launch 40 global reggae magazines, and we’re covering our beloved music from the four • Ernest Ranglin and The Sidewalk Doctors at London’s Jazz Cafe 41 corners of the world – from Kingston to Sidney, from Warsaw to New York. -

Narco-Narratives and Transnational Form: the Geopolitics of Citation in the Circum-Caribbean

Narco-narratives and Transnational Form: The Geopolitics of Citation in the Circum-Caribbean Jason Frydman [email protected] Brooklyn College Abstract: This essay argues that narco-narratives--in film, television, literature, and music-- depend on structures of narrative doubles to map the racialized and spatialized construction of illegality and distribution of death in the circum-Caribbean narco-economy. Narco-narratives stage their own haunting by other geographies, other social classes, other media; these hauntings refract the asymmetries of geo-political and socio-cultural power undergirding both the transnational drug trade and its artistic representation. The circum-Caribbean cartography offers both a corrective to nation- or language-based approaches to narco-culture, as well as a vantage point on the recursive practices of citation that are constitutive of transnational narco-narrative production. A transnational field of narrative production responding to the violence of the transnational drug trade has emerged that encompasses music and film, television and journalism, pulp and literary fiction. Cutting across nations, languages, genres, and media, a dizzying narrative traffic in plotlines, character-types, images, rhythms, soundtracks, expressions, and gestures travels global media channels through appropriations, repetitions, allusions, shoutouts, ripoffs, and homages. While narco-cultural production extends around the world, this essay focuses on the transnational frame of the circum-Caribbean as a zone of particularly dense, if not foundational, narrative traffic. The circum-Caribbean cartography offers 2 both a corrective to nation- or language-based approaches to narco-culture, as well as a vantage point on incredibly recursive practices of citation that are constitutive of the whole array of narco-narrative production: textual, visual, and sonic. -

Popcaan Releases "Numbers Don't Lie" Video

POPCAAN RELEASES "NUMBERS DON'T LIE" VIDEO WATCH HERE VANQUISH MIXTAPE OUT NOW VIA UNRULY/OVO SOUND LISTEN HERE March 15, 2020 (Toronto, Ont.) – Jamaican dancehall artist Popcaan unveils a new video for "Numbers Don't Lie," which is featured on his debut mixtape Vanquish [Unruly/OVO Sound]. The alluring visual portrays Popcaan recounting a young man's climb to success while also showcasing the breathtaking sights Jamaican culture has to offer. Popcaan narrates the journey at every stage from "Growth," "The Hustle" and "The Come Up." Check it out now and be on the lookout for more to come. PHOTO BY JAMAL BURGER DOWNLOAD PRESS PHOTO HERE ABOUT POPCAAN Jamaica’s Popcaan is an international superstar who has become synonymous with dancehall for the better part of a decade. Having made an impact initially via his association with Vybz Kartel, he went on to become a global sensation and was culturally relevant in the United States by the time he released his debut album, the critically-lauded Where We Come From, which debuted at #2 on Billboard's Reggae Albums chart in 2014. Popcaan has collaborated with many notable artists, including appearances on high-profile tracks like Jamie xx's "I Know There's Gonna Be (Good Times)," Drake’s “Know Yourself,” as well as Gorillaz' track "Saturnz Barz.” In 2018, he released his acclaimed sophomore full-length album Forever, which also debuted at #2 on Billboard's Reggae Albums Chart. In 2019, it was announced at Popcaan’s popular Unruly Fest that he signed to OVO Sound. FOLLOW POPCAAN: Twitter | Instagram | Facebook | YouTube For more information, please contact: Warner Records Yash Zadeh [email protected] . -

IRIE RECORDS New Release Catalogue 06-11 #2

IRIE RECORDS GMBH IRIE RECORDS GMBH BANK CONNECTION: NEW RELEASE CATALOGUE NO. 313 RINSCHEWEG 26 IRIE RECORDS GMBH (CD/LP/10"&12"/7"/DVDs) 48159 MUENSTER ACC. NO. 35 60 55, (16.06.2011 - 27.06.2011) GERMANY SORT CODE 400 501 50 TEL. 0251-45106 SPARKASSE MUENSTERLAND OST HOMEPAGE: www.irie-records.de MANAGING DIRECTOR: K.E. WEISS IBAN: DE32 4005 0150 0000 3560 55 EMAIL: [email protected] REG. OFFICE: MUENSTER/HRB 3638 SWIFT-BIC: WELADED1MST ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ IRIE RECORDS GMBH: DISTRIBUTION - WHOLESALE - RETAIL - MAIL ORDER - SHOP - YOUR SPECIALIST IN REGGAE & SKA -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- OPENING HOURS: MONDAY/TUESDAY/WEDNESDAY/THURSDAY/FRIDAY 13 – 19; SATURDAY 12 – 16 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ CD CD CD 2CD CD CD 1) 1) 1) CD 2CD 2CD CD CD CD 1) PLEASE NOTE: SPECIAL SALE PRICE ONLY VALID FOR ORDERS RECEIVED UNTIL 22.07.2011! IRIE RECORDS GMBH NEW RELEASE-CATALOGUE 06/2011 #2 SEITE 2 *** CDs *** HOLLIE COOK....................... HOLLIE COOK................... MR BONGO....... (GBR) (11/11). 18.49EUR GREGORY ISAACS (50 TRACKS; 1968-95 ON 2 CD)..... ALL I HAVE IS LOVE ANTHOLOGY.. TAD'S.......... (USA) (--/11). 21.99EUR 2CD J RAS (OF SOULIFTED).............. CITY OF TREES................. SOULIFTED...... (USA) (11/11). 16.99EUR KEVIN KINSELLA (FOUNDER OF JOHN BROWN'S BODY AND 10 FT. GANJA PLANT).......... GREAT DESIGN.................. ROIR........... (USA) (11/11). 17.99EUR MIDNITE........................... THE WAY....................... RASTAR......... (USA) (11/11). 18.99EUR SIZZLA............................ THE SCRIPTURES: MUSIC IN MY SO JOHN JOHN...... (JAM) (11/11). 17.99EUR SLIMMAH SOUND & LYRICAL BENJIE.... FIRM IN JAH: VOCAL & DUB SHOWC ROOTS TRIBE.... (NED) (11/11). 16.99EUR DAVID SOLID GOULD vs BILL LASWELL. -

Untitled Will Be out in Di Near Near Future Tracks on the Matisyahu Album, I Did Something with Like Inna Week Time

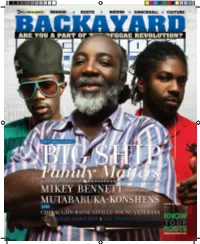

BACKAYARD DEEM TEaM Chief Editor Amilcar Lewis Creative/Art Director Noel-Andrew Bennett Managing Editor Madeleine Moulton (US) Production Managers Clayton James (US) Noel Sutherland Contributing Editors Jim Sewastynowicz (US) Phillip Lobban 3G Editor Matt Sarrel Designer/Photo Advisor Andre Morgan (JA) Fashion Editor Cheridah Ashley (JA) Assistant Fashion Editor Serchen Morris Stylist Judy Bennett Florida Correspondents Sanjay Scott Leroy Whilby, Noel Sutherland Contributing Photographers Tone, Andre Morgan, Pam Fraser Contributing Writers MusicPhill, Headline Entertainment, Jim Sewastynowicz, Matt Sarrel Caribbean Ad Sales Audrey Lewis US Ad Sales EL US Promotions Anna Sumilat Madsol-Desar Distribution Novelty Manufacturing OJ36 Records, LMH Ltd. PR Director Audrey Lewis (JA) Online Sean Bennett (Webmaster) [email protected] [email protected] JAMAICA 9C, 67 Constant Spring Rd. Kingston 10, Jamaica W.I. (876)384-4078;(876)364-1398;fax(876)960-6445 email: [email protected] UNITED STATES Brooklyn, NY, 11236, USA e-mail: [email protected] YEAH I SAID IT LOST AND FOUND It seems that every time our country makes one positive step forward, we take a million negative steps backward (and for a country with about three million people living in it, that's a lot of steps we are all taking). International media and the millions of eyes around the world don't care if it's just that one bad apple. We are all being judged by the actions of a handful of individuals, whether it's the politician trying to hide his/her indiscretions, to the hustler that harasses the visitors to our shores. It all affects our future. -

With Ty Dolla $Ign Is Finally Starting to Catch on with American Audiences, the Singer Only Sees His New Recording Home As a Tool to Push His Movement Forward

August 27, 2015 Kranium And Ty Dolla $ign Premiere The Video For "Nobody Has To Know" "This is not your typical dancehall video." Kranium's "Nobody Has To Know" is one of the most enduring dancehall songs this side of the aughts. Since it first dropped two years ago, it's been a bashment mainstay, perfect for dark corners and sweaty summer nights. The Atlantic signee recently recruited Ty Dolla $ign for a new version, and today he's dropping a video to go along with the DL-themed track. In the brightly hued video, Kranium skillfully evades paparazzi on a hoverboard before scooping his (presumably taken) woman and pulling up to a trailer for a middle-of- nowhere desert romp. Ty Dolla $ign is in the cut too, rolling through on a motorcycle with a fat blunt dangling from his lips. "Videos need to be creative and I think we pulled it off. This is not your typical dancehall video,” Kranium told The FADER over email. Accurate. Watch the video above, and hit the clip below for some behind-the-scenes views. June 15, 2015 Is Dancehall Going To Be Mainstream Again? 13 years after Dutty Rock, people in the music industry are ready to make dancehall pop again. Will they succeed? Once upon a time, Sean Paul was among the biggest pop stars in the world. His tour-de-force 2002 LP, Dutty Rock, charted in the Top 10 both in the US and in the UK. Singles like “Gimmie the Light” and “Get Busy” defined a slice of early aughts pop radio and earned the Jamaican singer a guest feature on Beyoncé’s debut album. -

JAMAICA MUSIC COUNTDOWN Jan 31

JAMAICA MUSIC COUNTDOWN By Richard ‘Richie B’ Burgess Jan 31 – Feb 6, 2020 TOP 25 DANCE HALL SINGLES TW LW WOC TITLE/ARTISTE/LABEL 01 3 9 W – Koffee feat. Gunna – Columbia Records (1wk@#1) U-2 02 2 16 Baller – TeeJay – Damage Musiq NM 03 1 16 Drone Dem – Vybz Kartel – Vybz Kartel Muzik (1wk@#1) D-2 04 5 11 Risky – Davido feat. Popcaan – Davido Worldwide U-1 05 4 11 Trust – Buju Banton – Gargamel Music (2wks@#1) D-1 06 7 13 Gyalis Story – Ding Dong – Dunwell Productions U-1 07 8 10 Find It – Elephant Man – Down Sound Records U-1 08 6 16 Leader – Masicka & Dexta Daps – Dunwell Productions (3wks@#1) D-2 09 13 7 Brik Pan Brik – Skillibeng – Claims Records U-4 10 11 8 Up Front – Govana – Chimney Records U-1 11 12 8 ADIADKING – Vybz Kartel – A-Team Lifestyle/Usain Bolt U-1 12 10 9 Like I’m Superman – Vybz Kartel & Sikka Rhymes – Frenz For Real (pp#10) D-2 13 16 6 Foreplay – Shenseea – Romeich Entertainment U-3 14 15 7 Aircraft – Aidonia – Chimney Records U-1 15 17 5 Then You…and Me – Vybz Kartel – Short Boss Muzik/ Vybz Kartel Muzik U-2 16 18 5 Bro Gad – Daddy 1 – Sky Bad Musiq U-2 17 9 15 Writing On The Wall – French Montana ft. Post Malone, Cardi B & Rvssian – Epic Records (pp#4) D-8 18 20 4 Top Shotta Is Back – Mavado – Chimney Records U-2 19 22 3 Under Vibes – Tommy Lee – Falmouth Dinesty /Boss Lady Muzik U-3 20 14 19 Dumpling ((Remix) – Stylo G feat. -

DJ Hero® 2 Unveils the Best Soundtrack in Entertainment

DJ Hero® 2 Unveils the Best Soundtrack in Entertainment --83 Original, Exclusive Mixes Feature Hand-Picked Roster of World-Renowned Musicians Highlighting the Biggest Names in Pop, Dance and Hip Hop Music Mixed by World's Hottest DJs --30-Second Video Clips of All 83 Mixes Now Available at www.djhero.com/music --Turntable Controller Bag by PUMA(R), MP3s of On-Disc Mixes and Character Unlock Cheats Among Pre-Order Offers at Retailers Online and Nationwide SANTA MONICA, Calif., Sept 21, 2010 /PRNewswire via COMTEX News Network/ -- In an all-new, unparalleled music experience featuring 83 original, exclusive mixes that spin together 105 speaker-blaring tracks and club-shaking anthems from over 100 of the biggest artists in pop, hip hop and dance, Activision Publishing, Inc. (Nasdaq: ATVI) today dropped the needle on DJ Hero (R) 2's full mix list that will transform living rooms into nightclubs with the best soundtrack in entertainment. Taking the soundtrack to "the most innovative and immersive music experience of 2009"* to the next level, when the party starts on October 19, budding beat chemists, singing sensations and all their friends will join together and experience these original, exclusive mixes such as Lady Gaga Mixed With Deadmau5, Iyaz Mixed With Rihanna, Eminem Mixed With Lil' Wayne, Kanye West Mixed With Metallica and a host of others magical musical creations. With in-game appearances, music and mixes from DJs keeping the speakers thumping in the world's hottest clubs, Deadmau5, David Guetta, DJ Qbert, DJ Shadow, DJ Z-Trip, RZA, and Tiesto among many others will start the DJ Hero 2 party off right. -

Songs by Title

Andromeda II DJ Entertainment Songs by Title www.adj2.com Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly A Dozen Roses Monica (I Got That) Boom Boom Britney Spears & Ying Yang Twins A Heady Tale Fratellis, The (I Just Wanna) Fly Sugar Ray A House Is Not A Home Luther Vandross (I'll Never Be) Maria Magdalena Sandra A Long Walk Jill Scott + 1 Martin Solveig & Sam White A Man Without Love Englebert Humperdinck 1 2 3 Miami Sound Machine A Matter Of Trust Billy Joel 1 2 3 4 I Love You Plain White T's A Milli Lil Wayne 1 2 Step Ciara & Missy Elliott A Moment Like This,zip Leona 1 Thing Amerie A Moument Like This Kelly Clarkson 10 Million People Example A Mover El Cu La Sonora Dinamita 10,000 Hours Dan + Shay, Justin Bieber A Night To Remember High School Musical 3 10,000 Nights Alphabeat A Song For Mama Boyz Ii Men 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters A Sunday Kind Of Love Reba McEntire 12 Days Of X Various A Team, The Ed Sheeran 123 Gloria Estefan A Thin Line Between Love & Hate H-Town 1234 Feist A Thousand Miles Vanessa Carlton 16 @ War Karina A Thousand Years Christina Perri 17 Forever Metro Station A Whole New World Zayn, Zhavia Ward 19-2000 Gorillaz ABC Jackson 5 1973 James Blunt Abc 123 Levert 1982 Randy Travis Abide With Me West Angeles Gogic 1985 Bowling For Soup About A Girl Sugababes 1999 Prince About You Now Sugababes 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The Abracadabra Steve Miller Band 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Nine Days 20 Years Ago Kenny Rogers Acapella Kelis 21 Guns Green Day According To You Orianthi 21 Questions 50 Cent Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus 21st Century Breakdown Green Day Act A Fool Ludacris 21st Century Girl Willow Smith Actos De Un Tonto Conjunto Primavera 22 Lily Allen Adam Ant Goody Two Shoes 22 Taylor Swift Adams Song Blink 182 24K Magic Bruno Mars Addicted To You Avicii 29 Palms Robert Plant Addictive Truth Hurts & Rakim 2U David Guetta Ft.