George Sarton: the Father of the History of Science. Part 1. Sarton's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Appear in Synthese Probability and Proximity in Surprise

Page 1 of 19 To appear in Synthese Probability and Proximity in Surprise Tomoji Shogenji1 Abstract This paper proposes an analysis of surprise formulated in terms of proximity to the truth, to replace the probabilistic account of surprise. It is common to link surprise to the low (prior) probability of the outcome. The idea seems sensible because an outcome with a low probability is unexpected, and an unexpected outcome often surprises us. However, the link between surprise and low probability is known to break down in some cases. There have been some attempts to modify the probabilistic account to deal with these cases, but they are still faced with problems. The new analysis of surprise I propose turns to accuracy (proximity to the truth) and identifies an unexpected degree of inaccuracy as reason for surprise. The shift from probability to proximity allows us to solve puzzles that strain the probabilistic account of surprise. Keywords Qualitative hypothesis ∙ Quantitative hypothesis ∙ Probabilistic hypothesis ∙ Inaccuracy ∙ Scoring rules ∙ Expected inaccuracy 1. Introduction This paper proposes an analysis of surprise formulated in terms of proximity to the truth, to replace the probabilistic account of surprise. It is common to link surprise to the low (prior) probability of the outcome.2 The idea seems sensible because an outcome with a low probability is unexpected, and an unexpected outcome often surprises us. However, the link between surprise and low probability is known to break down in some cases. There have been some attempts to modify the probabilistic account to deal with these cases, but as we shall see, they are still faced with problems. -

Hegel-Jahrbuch 2010 Hegel- Jahrbuch 2010

Hegel-Jahrbuch 2010 Hegel- Jahrbuch 2010 Begründet von Wilhelm Raimund Beyer (f) Herausgegeben von Andreas Arndt Paul Cruysberghs Andrzej Przylebski in Verbindung mit Lu De Vos und Peter Jonkers Geist? Erster Teil Herausgegeben von Andreas Arndt Paul Cruysberghs Andrzej Przylebski in Verbindung mit Lu De Vos und Peter Jonkers Akademie Verlag Redaktionelle Mitarbeit: Veit Friemert Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. ISBN 978-3-05-004638-9 © Akademie Verlag GmbH, Berlin 2010 Das eingesetzte Papier ist alterungsbeständig nach DIN/ISO 9706. Alle Rechte, insbesondere die der Übersetzung in andere Sprachen, vorbehalten. Kein Teil dieses Buches darf ohne schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages in irgendeiner Form - durch Photokopie, Mikroverfilmung oder irgendein anderes Verfahren - reproduziert oder in eine von Maschinen, insbesondere von Datenver- arbeitungsmaschinen, verwendbare Sprache übertragen oder übersetzt werden. Lektorat: Mischka Dammaschke Satz: Veit Friemert, Berlin Einbandgestaltung: nach einem Entwurf von Günter Schorcht, Schildow Druck: MB Medienhaus Berlin Printed in the Federal Republic of Germany VORWORT Das vorliegende Hegel-Jahrbuch umfasst den ersten Teil der auf dem XXVII. Internationalen He- gel-Kongress der Internationalen Hegel-Gesellschaft e.V. 2008 in Leuven zum Thema »Geist?« gehaltenen Referate. Den Dank an alle Förderer und Helfer, die den Kongress ermöglicht und zu dessen Gelingen beigetragen haben, hat Paul Cruysberghs - der zusammen mit Lu de Vos und Peter Jonkers das örtliche Organisationskomitee bildete - in seiner im folgenden abgedruckten Eröff- nungsrede abgestattet; ihm schließt sich der übrige Vorstand mit einem besonderen Dank an Paul Cruysberghs an. -

The Impact of Culture on Mindreading

Edinburgh Research Explorer The impact of culture on mindreading Citation for published version: Lavelle, JS 2019, 'The impact of culture on mindreading', Synthese, vol. N/A, pp. 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02466-5 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1007/s11229-019-02466-5 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Synthese General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 Synthese https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02466-5 FOLK PSYCHOLOGY: PLURALISTIC APPROACHES The impact of culture on mindreading Jane Suilin Lavelle1 Received: 8 July 2019 / Accepted: 4 November 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract The role of culture in shaping folk psychology and mindreading has been neglected in the philosophical literature. This paper shows that there are significant cultural dif- ferences in how psychological states are understood and used by (1) drawing on Spaulding’s recent distinction between the ‘goals’ and ‘methods’ of mindreading (2018) to argue that the relations between these methods vary across cultures; and (2) arguing that differences in folk psychology cannot be dismissed as irrelevant to the cognitive architecture that facilitates our understanding of psychological states. -

Pluralistic Perspectives on Logic: an Introduction

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Philosophy Faculty Publications Philosophy & Religious Studies 1-2020 Pluralistic Perspectives on Logic: An Introduction Colin R. Caret Teresa Kouri Kissel Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/philosophy_fac_pubs Part of the Logic and Foundations of Mathematics Commons, and the Philosophy of Science Commons Original Publication Citation Caret, C. R., & Kissel, T. K. Pluralistic perspectives on logic: An introduction. Synthese, 1-12. doi:10.1007/ s11229-019-02525-x This Editorial is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy & Religious Studies at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Synthese https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02525-x SI: PLURALISTIC PERSPECTIVES ON LOGIC Pluralistic perspectives on logic: an introduction Colin R. Caret1 · Teresa Kouri Kissel2 © Springer Nature B.V. 2020 1 Logic and logics Logical pluralism is the view that there are distinct, but equally good logics. Recent years have witnessed a sharp upswing of interest in this view, resulting in an impres- sive literature. We only expect this trend to continue in the future. More than one commentator has, however, expressed exasperation at the view: what can it mean to be a pluralist about logic of all things? [see, e.g., Eklund (2017); Goddu (2002); Keefe (2014)]. In this introduction, we aim to set out the basic pluralist position, identify some issues over which pluralists disagree amongst themselves, and highlight the topics at the heart of the ongoing debate. -

Chimpanzee Mind Reading: Don't Stop Believing

Received: 18 April 2016 Revised: 22 September 2016 Accepted: 24 October 2016 DOI 10.1111/phc3.12394 ARTICLE Chimpanzee mind reading: Don't stop believing Kristin Andrews York University, Canada Abstract Correspondence “ ” Kristin Andrews, Department of Philosophy, Since the question Do chimpanzees have a theory of mind? was York University, Toronto, Canada. raised in 1978, scientists have attempted to answer it, and Email: [email protected] philosophers have attempted to clarify what the question means and whether it has been, or could be, answered. Mindreading (a term used mostly by philosophers) or theory of mind (a term preferred by scientists) refers to the ability to attribute mental states to other individuals. Some versions of the question focus on whether chimpanzees engage in belief reasoning or can think about false belief, and chimpanzees have been given nonverbal versions of the false belief moved‐object task (also known as the Sally–Anne task). Other versions of the question focus on whether chimpanzees understand what others can see, and chimpanzees can pass those tests. From this data, some claim that chimpanzees know something about perceptions, but nothing about belief. Others claim that chimpanzees do not understand belief or perceptions, because the data fails to overcome the “logical problem,” and permits an alternative, non‐mentalistic interpretation. I will argue that neither view is warranted. Belief reasoning in chimpanzees has focused on examining false belief in a moved object scenario, but has largely ignored other functions of belief. The first part of the paper is an argument for how to best understand belief reasoning and offers suggestion for future investigation. -

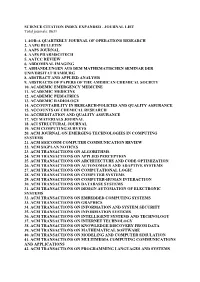

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total Journals: 8631

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total journals: 8631 1. 4OR-A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF OPERATIONS RESEARCH 2. AAPG BULLETIN 3. AAPS JOURNAL 4. AAPS PHARMSCITECH 5. AATCC REVIEW 6. ABDOMINAL IMAGING 7. ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG 8. ABSTRACT AND APPLIED ANALYSIS 9. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY 10. ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE 11. ACADEMIC MEDICINE 12. ACADEMIC PEDIATRICS 13. ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY 14. ACCOUNTABILITY IN RESEARCH-POLICIES AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 15. ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH 16. ACCREDITATION AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 17. ACI MATERIALS JOURNAL 18. ACI STRUCTURAL JOURNAL 19. ACM COMPUTING SURVEYS 20. ACM JOURNAL ON EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES IN COMPUTING SYSTEMS 21. ACM SIGCOMM COMPUTER COMMUNICATION REVIEW 22. ACM SIGPLAN NOTICES 23. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ALGORITHMS 24. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON APPLIED PERCEPTION 25. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ARCHITECTURE AND CODE OPTIMIZATION 26. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON AUTONOMOUS AND ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS 27. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTATIONAL LOGIC 28. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER SYSTEMS 29. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER-HUMAN INTERACTION 30. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DATABASE SYSTEMS 31. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DESIGN AUTOMATION OF ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS 32. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON EMBEDDED COMPUTING SYSTEMS 33. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON GRAPHICS 34. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION AND SYSTEM SECURITY 35. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION SYSTEMS 36. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS AND TECHNOLOGY 37. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTERNET TECHNOLOGY 38. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON KNOWLEDGE DISCOVERY FROM DATA 39. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MATHEMATICAL SOFTWARE 40. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MODELING AND COMPUTER SIMULATION 41. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MULTIMEDIA COMPUTING COMMUNICATIONS AND APPLICATIONS 42. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES AND SYSTEMS 43. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON RECONFIGURABLE TECHNOLOGY AND SYSTEMS 44. -

Download Curriculum Vitae

PAGE 1 Office of Academic Affairs DAVIS BAIRD Clark University, 950 Main St., Worcester, MA 01610 (508) 793-7673, FAX: 793-8834, [email protected] Education 1978-1981 Ph.D. Stanford University, Philosophy of Science, Philosophy of Language and Logic 1977-1978 A.M. Stanford University, Philosophy of Science 1972-1976 A.B. Brandeis University, Mathematics and Philosophy, cum laude, with High Honors in Philosophy Academic Positions 2010- Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs, Clark University 2010- Professor of Philosophy, Clark University 2010- Distinguished Professor Emeritus and Dean Emeritus, University of South Carolina 2005-2010 Dean, South Carolina Honors College, University of South Carolina 2004-2010 Louise Fry Scudder Professor, Department of Philosophy, University of South Carolina 1992-2005 Chair, Department of Philosophy 2001-2004 Professor, Department of Philosophy, University of South Carolina 1988-2001 Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy, University of South Carolina 1999-2000 Senior Fellow, Dibner Institute for the History of Science and Technology, M.I.T. 1982-1988 Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, University of South Carolina 1981-1982 Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, University of Arizona 1981 Instructor, Department of Philosophy, Stanford University Professional Service 2011- Fellow, American Association for the Advancement of Science 2013- Consulting Editor, NanoEthics 2013- Editorial Board, Acta Baltica Historae et Philosophiae Sciantiarum 2003- Grant reviewer -

Michael Rescorla

February 9, 2020 Michael Rescorla Department of Philosophy University of California Los Angeles, CA 90095 [email protected] Employment Professor, Summer 2016 to present Department of Philosophy, University of California, Los Angeles Professor, Summer 2015 to Spring 2016 Department of Philosophy, University of California, Santa Barbara Associate Professor, Summer 2009 to Spring 2015 Department of Philosophy, University of California, Santa Barbara Assistant Professor, Fall 2003 to Spring 2009 Department of Philosophy, University of California, Santa Barbara Education Harvard University, Ph.D., Philosophy, June 2003 Dissertation: Is Thought Explanatorily Prior to Language? Harvard University, B.A., Summa Cum Laude, Philosophy and Mathematics, June 1997 Senior Thesis: Forcing, Atoms, and Choice Published Papers “Reifying Representations,” What Are Mental Representations?, eds. Joulia Smorthchkova, Tobias Schlicht, and Krzysztof Dolega. Oxford: Oxford University Press (forthcoming). “An Improved Dutch Book Theorem for Conditionalization,” Erkenntnis (published on-line; print version forthcoming). “On the Proper Formulation of Conditionalization,” Synthese (published on-line; print version forthcoming). “How Particular Is Perception?”. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 100 (2020): pp. 721- 727. (Contribution to a book symposium on Susanna Schellenberg’s The Unity of Perception.) “Perceptual Co-Reference,” The Review of Philosophy and Psychology (published on-line; print version forthcoming). “A Realist Perspective on Bayesian Cognitive Science,” Inference and Consciousness, eds. Anders Nes and Timothy Chan. Routledge (2020): pp. 40-73. “A Dutch Book Theorem and Converse Dutch Book Theorem for Kolmogorov Conditionalization,” The Review of Symbolic Logic 11 (2018): pp. 705-735. “Motor Computation,” The Routledge Handbook of the Computational Mind, eds. Matteo Colombo and Mark Sprevak. Routledge (2018): pp. 424-435. -

Abbreviations of Names of Serials

Abbreviations of Names of Serials This list gives the form of references used in Mathematical Reviews (MR). ∗ not previously listed The abbreviation is followed by the complete title, the place of publication x journal indexed cover-to-cover and other pertinent information. y monographic series Update date: January 30, 2018 4OR 4OR. A Quarterly Journal of Operations Research. Springer, Berlin. ISSN xActa Math. Appl. Sin. Engl. Ser. Acta Mathematicae Applicatae Sinica. English 1619-4500. Series. Springer, Heidelberg. ISSN 0168-9673. y 30o Col´oq.Bras. Mat. 30o Col´oquioBrasileiro de Matem´atica. [30th Brazilian xActa Math. Hungar. Acta Mathematica Hungarica. Akad. Kiad´o,Budapest. Mathematics Colloquium] Inst. Nac. Mat. Pura Apl. (IMPA), Rio de Janeiro. ISSN 0236-5294. y Aastaraam. Eesti Mat. Selts Aastaraamat. Eesti Matemaatika Selts. [Annual. xActa Math. Sci. Ser. A Chin. Ed. Acta Mathematica Scientia. Series A. Shuxue Estonian Mathematical Society] Eesti Mat. Selts, Tartu. ISSN 1406-4316. Wuli Xuebao. Chinese Edition. Kexue Chubanshe (Science Press), Beijing. ISSN y Abel Symp. Abel Symposia. Springer, Heidelberg. ISSN 2193-2808. 1003-3998. y Abh. Akad. Wiss. G¨ottingenNeue Folge Abhandlungen der Akademie der xActa Math. Sci. Ser. B Engl. Ed. Acta Mathematica Scientia. Series B. English Wissenschaften zu G¨ottingen.Neue Folge. [Papers of the Academy of Sciences Edition. Sci. Press Beijing, Beijing. ISSN 0252-9602. in G¨ottingen.New Series] De Gruyter/Akademie Forschung, Berlin. ISSN 0930- xActa Math. Sin. (Engl. Ser.) Acta Mathematica Sinica (English Series). 4304. Springer, Berlin. ISSN 1439-8516. y Abh. Akad. Wiss. Hamburg Abhandlungen der Akademie der Wissenschaften xActa Math. Sinica (Chin. Ser.) Acta Mathematica Sinica. -

History of Biology in the Netherlands a Historical

HISTORY OF BIOLOGY IN THE NETHERLANDS A HISTORICAL SKETCH Bert Theunissen and Robert P.W. Visser As in most coimtries, the history of biology as an academic discipline is of relatively recent origin in the Netherlands. The first full-time professionals were appointed in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Their number has never been large, and one sometimes worries that the entire population may one day be wiped out by sheer 'drift'. Yet so far we've managed to stay alive - in fact, the prospects are not too bad at the moment. As elsewhere, the professional historians of biology in the Netherlands were preceded by generations of enthusiastic amateurs. We shall not even try to give all of them their due share in this overview, restricting our account to some general remarks on developments over the last century and to a few representative twen tieth-century figures. The historical genres to flourish the most in the pre-professional era were biographies, publications of the 'life and work' type, and commemorative volumes. A useful bibliography of the more important works published from the beginning of the century up to the early 1960s can be found in a review compiled by Frans Verdoorn in 1%3.' Among the Dutch biologists who showed more than a fleeting interest in the history of their discipline and whose works clearly transcend the status of occasional writings, two of the most outstanding are F.W.T. Hunger and A. Schierbeek. They paved the way for the professionalization of the discipline in the Netherlands, particularly in that their activities and pubHcations aroused a lasting interest in the history of biology in Dutch academic circles. -

Views of Western Scholars on George Sarton's Introduction to the History

International Journal of Business and Social Science Vol. 5, No. 7(1); June 2014 Views of Western Scholars on George Sarton’s Introduction to the History of Science Nabihah Liyana Salan Roziah Sidik @ Mat Sidek Department of Arabic Studies and Islamic Civilization Faculty of Islamic Studies Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Selangor, Malaysia. Abstract This article discusses an outstanding founder figure of the discipline of history of science, namely George Sarton who contributed many works, including books and articles. His most notable success is the three-volume Introduction to the History of Science. This work contains biographies of great scientists throughout time including scientists of the Islamic civilization. In fact, the writing of this work bears references to sources of authority in the Islamic civilization. This work has also been given a distinctive evaluation by Western scholars. Thus, the purpose of this article is to examine Western scholars’ views on Sarton’s work, Introduction to the History of Science. The research methodology used is a qualitative approach by content analysis as reference sources are document in form. Besides that, a hermeneutic approach is also used to make interpretations of the work. The scope of this research focuses on the work Introduction to the History of Science and Western scholars’ views on it. Research results find that Introduction to the History of Science had received a positive response from Western scholars such as E.G.B. and Francis R.Johnson even though George Sarton had in fact referred to authoritative sources in Arabic language, particularly when discussing scientific figures in the Islamic civilization. -

History and the History of Science in the Work of Hendrik De

History and t!" history of s$i"n$" in t!" %or& of H"ndri& '" (an CHRI)T*+H,-.,RBR/GG,N1 L"$t0r"r 1 /ni2"rsit"it G"nt L,3I) +4,N)*N 55555555555555555555555555555555555555555 +ro#"ssor 1 3"st"rn (i$!i6an /ni2"rsity H"ndri& '" (an 71885-1953) is r":":;"r" as one of t!" :ost si6ni#i$ant innovators in t!" (arxist tra ition 0ring t!" int"r%ar period. =n ind"#ati6a;>" and %i ">y tra2">>" t!"or"ti$ian, !" ":"r6" as a :a?or politi$a> >"a "r in t!" 1930s and t!"n ;"$a:" ;"st &nown #or his a$$om:odation %it! t!" G"r:an oc$upi"r during t!" )"$ond 3or> 3ar. '" (an's int">>"$tua> and po>iti$a> in#>0"nc" spr"a #ar ;"yond t!" bor "rs o# !is nati2" B">6i0:. His $ordia> r">ations!ip %it! t!" historian H"nri +ir"nn" 71862-1935) has ;""n obs"r2"d. Inde"d, '" (an %as one of +ir"nne@s :ost bri>>iant pupi>s. '" (an's $onne$tion %it! s$holars a>so "xt"nde to historian of s$i"nc" G"or6" )arton 71884-1956). In t!" #ol>owing pa6"s, %" dis$uss %hat-'" (an dr"%-#rom bot!-+ir"nn" and-)arton. H"nri +ir"nne, by 2irt0" of his socia> and "$onomi$ history 1 %hi$! >" dir"$t>y into (ar$ B>oc! and L0$i"n B";2r"@s Annales 1 provi " a :a?or int">>"$tua> i:petus #or t!" dis$ip>in" of history as it is pra$ti$" today 7Lyon C Lyon, 1991).