Beginning of Modern Nationalism in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Série Antropologia 103 Three Essays on Anthropology in India

Universidade de Brasília Instituto de Ciências Humanas Departamento de Antropologia 70910.900 – Brasília, DF Fone: +55 61 3307 3006 Série Antropologia 103 Three essays on anthropology in India Mariza Peirano This issue brings together the translation into English of numbers 57, 65 and 83 of Série Antropologia. The present title replaces the former “Towards Anthropo- logical Reciprocity”, its designation from 1990 to 2010. 1990 Table of contents Introduction .............................................................................. 2 Acknowledgements .................................................................. 7 Paper 1: On castes and villages: reflections on a debate.............. 8 Paper 2: “Are you catholic?” Travel report, theoretical reflections and ethical perplexities ………………….. 26 Paper 3: Anthropological debates: the India – Europe dialogue ...................................................... 54 1 Introduction The three papers brought together in this volume of Série Antropologia were translated from Portuguese into English especially to make them available for an audience of non- Brazilian anthropologists and sociologists. The papers were written with the hope that a comparison of the Brazilian with the Indian academic experience could enlarge our understanding of the social, historical and cultural implications of the development of anthropology in different contexts. This project started in the late 1970’s when, as a graduate student at Harvard University, I decided to take a critical look at the dilemmas that face -

Chapter 9. the Programme and Achievements of the Early Nationalist

Chapter 9. The Programme and Achievements of the Early Nationalist Very Short Questions Question 1: Name the sections into which the Congress was divided from its very inception. Answer: The Moderates and the Assertives. Question 2: During which period did the Moderates dominate the Congress? Answer: The Moderates dominated the Congress from 1885 to 1905. Question 3: Name any three important leaders of the Moderates. Or Name two leaders of the Moderates. Answer: The three important leaders of the moderates were: (i) Dadabhai Naoroji (ii) Surendra Nath Banerjee (iii) Gopal Krishna Gokhale. Question 4: What were the early nationalists called? Answer: They were called the ‘Moderates’. Question 5: Why were the early nationalists called ‘Moderates’? Answer: The early nationalists had full faith in the sense of justice of the British. For this reason their demands as well as there methods help them in winning the title of ‘Moderates’. Question 6: Who were the Moderates ? Answer: They were the early nationalists, who believed that the British always show a sense of justice in all spheres of their Government. Question 7: State any two demands of the Moderates in respect of economic reforms. Answer: (i) Protection of Indian industries. (ii) Reduction of land revenue. Question 8: State any two demands of the Moderates in respect of political reforms. Answer: (i) Expansion of Legislative Councils. (ii) Separation between the Executive and the Judiciary. Question 9: Mention two demands of the Moderates in respect of administrative reforms. Answer: (i) Indianisation of Civil Services. (ii) Repeal of Arms Act. Question 10: What did the Moderates advocate in the field of civil rights? Answer: The Moderates opposed the curbs imposed on freedom of speech, press and association. -

A Crisis of Commitment: Socialist Internationalism in British Columbia During the Great War

A Crisis of Commitment: Socialist Internationalism in British Columbia during the Great War by Dale Michael McCartney B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2004 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of History © Dale Michael McCartney 2010 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2010 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for Fair Dealing. Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. APPROVAL Name: Dale Michael McCartney Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: A Crisis of Commitment: Socialist Internationalism in British Columbia during the Great War Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Emily O‘Brien Assistant Professor of History _____________________________________________ Dr. Mark Leier Senior Supervisor Professor of History _____________________________________________ Dr. Karen Ferguson Supervisor Associate Professor of History _____________________________________________ Dr. Robert A.J. McDonald External Examiner Professor of History University of British Columbia Date Defended/Approved: ________4 March 2010___________________________ ii Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. -

The Intersection of Racial and Sexual Marginalisation and Repression in Rex Vs Singh (2008) and Seeking Single White Male (2010) by Yilong (Louie) Liu

Confronting Ambiguity: The Intersection of Racial and Sexual Marginalisation and Repression in Rex vs Singh (2008) and Seeking Single White Male (2010) By Yilong (Louie) Liu A major research paper presented to OCAD University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Contemporary Art, Design, and New Media Art Histories Toronto, Ontario, Canada, April 2018 ©Yilong Liu, 2018 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this major research paper. This is a true copy of the major research paper, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorise OCAD University to lend this major research paper to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my major research paper may be made electronically available to the public. I further authorise OCAD University to reproduce this major research paper by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. Signature___________ ii Abstract This MRP examines how Canadian filmmakers and artists explore racial and sexual marginalisation in Canada. Two films in particular exemplify different forms of racism towards South Asian immigrants. The first, Rex vs Singh (2008), an experimental documentary produced by John Greyson, Richard Fung, and Ali Kazimi, showcases the ambiguous application of immigration policies to repress South Asian immigration. Through different reconstructed montages, the film confronts these ambiguities in relation to the court case. The second, Seeking Single White Male (2010), a performance-video work by Toronto-based artist Vivek Shraya—South Asian descent, demonstrates not only the dominant racial norms and white normativity in queer communities in Toronto, but also the ambivalence in performing racial identification. -

A.R. Desai: Social Background of Indian Nationalism

M.A. (Sociology) Part I (Semester-II) Paper III L .No. 2.2 Author : Prof. B.K. Nagla A.R. Desai: Social Background of Indian Nationalism Structure 2.2.0 Objectives 2.2.1 Introduction to the Author 2.2.2 Writing of Desai 2.2.3 Nationalism 2.2.3.1 Nation : E.H. Carr's definition 2.2.3.2 National Sentiment 2.2.3.3 Study of Rise and Growth of Indian Nationalism 2.2.3.4 Social Background of Indian Nationalism 2.2.4 Discussion 2.2.5 Nationalism in India, Its Chief Phases 2.2.5.1 First Phase 2.2.5.2 Second Phase 2.2.5.3 Third Phase 2.2.5.4 Fourth Phase 2.2.5.5 Fifth Phase 2.2.6 Perspective 2.2.7 Suggested Readings 2.2.0 Objectives: After going through this lesson you will be able to : • introduce the Author. • explain Nationalism. • discuss rise and growth of Indian Nationalism. • know Nationalism in India and its different phases. 2.2.1 Introduction to the Author A.R.Desai: (1915-1994) Akshay Ramanlal Desai was born on April 16, 1915 at Nadiad in Central Gujarat and died on November 12, 1994 at Baroda in Gujarat. In his early ears, he was influenced by his father Ramanlal Vasantlal Desai, a well-known litterateur who inspired the youth in Gujarat in the 30s. A.R.Desai took part in student movements in Baroda, Surat and Bombay. He graduated from the university of M.A. (Sociology) Part I 95 Paper III Bombay, secured a law degree and a Ph.D. -

Modern Indian Political Thought Ii Modern Indian Political Thought Modern Indian Political Thought Text and Context

Modern Indian Political Thought ii Modern Indian Political Thought Modern Indian Political Thought Text and Context Bidyut Chakrabarty Rajendra Kumar Pandey Copyright © Bidyut Chakrabarty and Rajendra Kumar Pandey, 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. First published in 2009 by SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd B1/I-1 Mohan Cooperative Industrial Area Mathura Road, New Delhi 110 044, India www.sagepub.in SAGE Publications Inc 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, California 91320, USA SAGE Publications Ltd 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP, United Kingdom SAGE Publications Asia-Pacifi c Pte Ltd 33 Pekin Street #02-01 Far East Square Singapore 048763 Published by Vivek Mehra for SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd, typeset in 10/12 pt Palatino by Star Compugraphics Private Limited, Delhi and printed at Chaman Enterprises, New Delhi. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chakrabarty, Bidyut, 1958– Modern Indian political thought: text and context/Bidyut Chakrabarty, Rajendra Kumar Pandey. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Political science—India—Philosophy. 2. Nationalism—India. 3. Self- determination, National—India. 4. Great Britain—Colonies—India. 5. India— Colonisation. 6. India—Politics and government—1919–1947. 7. India— Politics and government—1947– 8. India—Politics and government— 21st century. I. Pandey, Rajendra Kumar. II. Title. JA84.I4C47 320.0954—dc22 2009 2009025084 ISBN: 978-81-321-0225-0 (PB) The SAGE Team: Reema Singhal, Vikas Jain, Sanjeev Kumar Sharma and Trinankur Banerjee To our parents who introduced us to the world of learning vi Modern Indian Political Thought Contents Preface xiii Introduction xv PART I: REVISITING THE TEXTS 1. -

Contributions of Lala Har Dayal As an Intellectual and Revolutionary

CONTRIBUTIONS OF LALA HAR DAYAL AS AN INTELLECTUAL AND REVOLUTIONARY ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF ^ntiat ai pijtl000pi{g IN }^ ^ HISTORY By MATT GAOR CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2007 ,,» '*^d<*'/. ' ABSTRACT India owes to Lala Har Dayal a great debt of gratitude. What he did intotality to his mother country is yet to be acknowledged properly. The paradox ridden Har Dayal - a moody idealist, intellectual, who felt an almost mystical empathy with the masses in India and America. He kept the National Independence flame burning not only in India but outside too. In 1905 he went to England for Academic pursuits. But after few years he had leave England for his revolutionary activities. He stayed in America and other European countries for 25 years and finally returned to England where he wrote three books. Har Dayal's stature was so great that its very difficult to put him under one mould. He was visionary who all through his life devoted to Boddhi sattava doctrine, rational interpretation of religions and sharing his erudite knowledge for the development of self culture. The proposed thesis seeks to examine the purpose of his returning to intellectual pursuits in England. Simultaneously the thesis also analyses the contemporary relevance of his works which had a common thread of humanism, rationalism and scientific temper. Relevance for his ideas is still alive as it was 50 years ago. He was true a patriotic who dreamed independence for his country. He was pioneer for developing science in laymen and scientific temper among youths. -

Nationalism in India Lesson

DC-1 SEM-2 Paper: Nationalism in India Lesson: Beginning of constitutionalism in India Lesson Developer: Anushka Singh Research scholar, Political Science, University of Delhi 1 Institute of Lifelog learning, University of Delhi Content: Introducing the chapter What is the idea of constitutionalism A brief history of the idea in the West and its introduction in the colony The early nationalists and Indian Councils Act of 1861 and 1892 More promises and fewer deliveries: Government of India Acts, 1909 and 1919 Post 1919 developments and India’s first attempt at constitution writing Government of India Act 1935 and the building blocks to a future constitution The road leading to the transfer of power The theory of constitutionalism at work Conclusion 2 Institute of Lifelog learning, University of Delhi Introduction: The idea of constitutionalism is part of the basic idea of liberalism based on the notion of individual’s right to liberty. Along with other liberal notions,constitutionalism also travelled to India through British colonialism. However, on the one hand, the ideology of liberalism guaranteed the liberal rightsbut one the other hand it denied the same basic right to the colony. The justification to why an advanced liberal nation like England must colonize the ‘not yet’ liberal nation like India was also found within the ideology of liberalism itself. The rationale was that British colonialism in India was like a ‘civilization mission’ to train the colony how to tread the path of liberty.1 However, soon the English educated Indian intellectual class realised the gap between the claim that British Rule made and the oppressive and exploitative reality of colonialism.Consequently,there started the movement towards autonomy and self-governance by Indians. -

The Ghadar Movement: Why Socialists Should Learn About It

Socialist Studies / Études socialistes 13 (2) Fall 2018 Copyright © 2018 The Author(s) Article THE GHADAR MOVEMENT: WHY SOCIALISTS SHOULD LEARN ABOUT IT RADHA D’SOUZA University of Westminster KASIM ALI TIRMIZEY York University Exile did not suit me, I took it for my homeland When the noose of my net tightened, I called it my nest. Mirza Asadullah Khan “Ghalib” [b. December 1797, Agra, India, d. February 1869, Delhi, India]1 I In May 2016 Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau formally apologized on behalf of the Government of Canada for the 1914 Komagata Maru incident, a singular event in the anti-colonial struggle against the British Empire launched by the newly formed Ghadar Party in North America. The apology came even as the anti-migrant vitriol in the wider society amplified. In late 2013 and again in early 2014, a memorial for the Ghadar martyrs in Harbour Green Park in Vancouver was vandalised twice within months. Notwithstanding the antagonism against immigrants in the public domain, Trudeau’s apology had settled Canada’s accounts with history and able to “move on.” The Trudeau government appointed Harjit Sajjan, a retired Lieutenant Colonel and war veteran in the Canadian Army as the defence minister, the first South Asian to hold the position. In 2011, Harjit Singh was interestingly made the commanding officer of one of the Canadian Army regiments that was historically involved in preventing passengers aboard the Komagata Maru from disembarking. Harjit Sajjan was deployed in Afghanistan where he used his familiarity with language, culture and traditions of the region in favour of imperialist agendas in the region, the very Afghanistan where the Ghadarites from his home state were instrumental in establishing the first government-in-exile of free India a hundred years ago. -

Bipin Chandra Pal

Bipin Chandra Pal March 15, 2021 In news : Recently, Union Minister of Information and Broadcasting (IB) inaugurated a photo-exhibition to showcase the struggles of various freedom fighters Bipin Chandra Pal is one of them A brief History of Bipin Chandra Pal He was an Indian nationalist, writer, orator, social reformer and Indian independence movement freedom fighter Birth: 7th November 1858, Habiganj Sylhet district, Bangladesh Bipin ji He was one third of the “Lal Bal Pal” triumvirat Education: He studied and taught at the Church Mission Society College (now the St. Paul’s Cathedral Mission College), an affiliated college of the University of Calcutta Brahmo Samaj: After his first wife died, he married a widow and joined the Brahmo Samaj He was also associated with Indian National Congress and India House His Contributions: He known as the Father of Revolutionary Thoughts in India and was one of the freedom fighters of India Pal stood against the partition of Bengal by the colonial British government. 1887: He made a strong plea for repeal of the Arms Act which was discriminatory in nature He was one of the main architects of the Swadeshi movement along with Sri Aurobindo. He popularized the concepts of swadeshi (exclusive use of Indian-made goods) and swaraj His programme consisted of Swadeshi, boycott and national education. He preached and encouraged the use of Swadeshi and the boycott of foreign goods to eradicate poverty and unemployment. Bipin wanted to remove social evils from the form and arouse the feelings of nationalism through national criticism. He also set up a school called Anushilan Samiti and began a tour of the country to propagate his philosophy. -

History & Civics the Indian National Congress Originated in 1885 A.D.At That Time,The Leaders of the Indian National Congres

History & Civics The Indian National Congress originated in 1885 A.D.At that time,the leaders of the Indian National Congress were the Moderates.But during the rule of Lord Curzon due to repressive policy of the British,the differences were created among the leaders of the INC.A group of leaders came into existence who did not believe in sympathy and justice of the British Government in India.They were called the Assertive Nationalists.Lala Lajpat Rai,Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Bipin Chandra Pal were the main leaders of the Assertives. Objectives:Achievement of Swaraj,Disestablishment of the relations between India and England.The Assertive Nationalist used self reliance and self sacrifice,sufferings and hardships for achieving their aim. The Early Nationalists did not fully approve the resolutions passed by the Assertive Nationalist in 1906,as a result this led to a split in the Congress in 1907. Bal Gangadhar Tilak:He was also known as Lokmanya.He organized Akharas and Lathi Clubs.His famous slogan was ‘Swaraj is my birthright and I will have it’.Through the Ganapati festival and revival of Shivaji festival in Maharashtra he installed a spirit of glory and patriotism. Bipin Chandra Pal:He was a great supporter of National Education.He opposed the partition of Bengal by spreading the message of boycott,swadeshi and national education.He also championed the cause of women education and opposed caste system. Lala Lajpat Rai:He was influenced by Tilak’s philosophy.His courage and determination have earned him the title of ‘Sher-i-Punjab’.He is remembered for his patriotism,courage and revolutionary ideas. -

Checkpoint History Civics X Answers

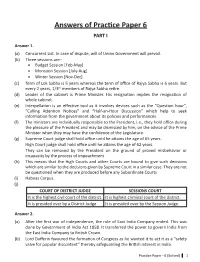

Answers of Practice Paper 6 PART I Answer 1. (a) Concurrent List. In case of dispute, will of Union Government will prevail. (b) Three sessions are:- • Budget Session [Feb-May] • Monsoon Session [July-Aug] • Winter Session [Nov-Dec] (c) Term of Lok Sabha is 5 years whereas the term of office of Rajya Sabha is 6 years. But every 2 years, 1/3rd members of Rajya Sabha retire. (d) Leader of the cabinet is Prime Minister. His resignation implies the resignation of whole cabinet. (e) Interpellation is an effective tool as it involves devices such as the “Question hour”, “Calling Attention Notices” and “Half-an-Hour Discussion” which help to seek information from the government about its policies and performances. (f) The ministers are individually responsible to the President, i.e., they hold office during the pleasure of the President and may be dismissed by him, on the advice of the Prime Minister when they may have the confidence of the Legislature. (g) Supreme Court judge shall hold office until he attains the age of 65 years. High Court judge shall hold office until he attains the age of 62 years. They can be removed by the President on the ground of proved misbehavior or incapacity by the process of impeachment. (h) This means that the High Courts and other Courts are bound to give such decisions which are similar to the decisions given by Supreme Court in a similar case. They are not be questioned when they are produced before any Subordinate Courts. (i) Habeas Corpus. (j) COURT OF DISTRICT JUDGE SESSIONS COURT It is the highest civil court of the district.