UNIT 26 the WORKING CLASS* the Peasantry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 9. the Programme and Achievements of the Early Nationalist

Chapter 9. The Programme and Achievements of the Early Nationalist Very Short Questions Question 1: Name the sections into which the Congress was divided from its very inception. Answer: The Moderates and the Assertives. Question 2: During which period did the Moderates dominate the Congress? Answer: The Moderates dominated the Congress from 1885 to 1905. Question 3: Name any three important leaders of the Moderates. Or Name two leaders of the Moderates. Answer: The three important leaders of the moderates were: (i) Dadabhai Naoroji (ii) Surendra Nath Banerjee (iii) Gopal Krishna Gokhale. Question 4: What were the early nationalists called? Answer: They were called the ‘Moderates’. Question 5: Why were the early nationalists called ‘Moderates’? Answer: The early nationalists had full faith in the sense of justice of the British. For this reason their demands as well as there methods help them in winning the title of ‘Moderates’. Question 6: Who were the Moderates ? Answer: They were the early nationalists, who believed that the British always show a sense of justice in all spheres of their Government. Question 7: State any two demands of the Moderates in respect of economic reforms. Answer: (i) Protection of Indian industries. (ii) Reduction of land revenue. Question 8: State any two demands of the Moderates in respect of political reforms. Answer: (i) Expansion of Legislative Councils. (ii) Separation between the Executive and the Judiciary. Question 9: Mention two demands of the Moderates in respect of administrative reforms. Answer: (i) Indianisation of Civil Services. (ii) Repeal of Arms Act. Question 10: What did the Moderates advocate in the field of civil rights? Answer: The Moderates opposed the curbs imposed on freedom of speech, press and association. -

Modern Indian Political Thought Ii Modern Indian Political Thought Modern Indian Political Thought Text and Context

Modern Indian Political Thought ii Modern Indian Political Thought Modern Indian Political Thought Text and Context Bidyut Chakrabarty Rajendra Kumar Pandey Copyright © Bidyut Chakrabarty and Rajendra Kumar Pandey, 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. First published in 2009 by SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd B1/I-1 Mohan Cooperative Industrial Area Mathura Road, New Delhi 110 044, India www.sagepub.in SAGE Publications Inc 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, California 91320, USA SAGE Publications Ltd 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP, United Kingdom SAGE Publications Asia-Pacifi c Pte Ltd 33 Pekin Street #02-01 Far East Square Singapore 048763 Published by Vivek Mehra for SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd, typeset in 10/12 pt Palatino by Star Compugraphics Private Limited, Delhi and printed at Chaman Enterprises, New Delhi. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chakrabarty, Bidyut, 1958– Modern Indian political thought: text and context/Bidyut Chakrabarty, Rajendra Kumar Pandey. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Political science—India—Philosophy. 2. Nationalism—India. 3. Self- determination, National—India. 4. Great Britain—Colonies—India. 5. India— Colonisation. 6. India—Politics and government—1919–1947. 7. India— Politics and government—1947– 8. India—Politics and government— 21st century. I. Pandey, Rajendra Kumar. II. Title. JA84.I4C47 320.0954—dc22 2009 2009025084 ISBN: 978-81-321-0225-0 (PB) The SAGE Team: Reema Singhal, Vikas Jain, Sanjeev Kumar Sharma and Trinankur Banerjee To our parents who introduced us to the world of learning vi Modern Indian Political Thought Contents Preface xiii Introduction xv PART I: REVISITING THE TEXTS 1. -

History & Civics the Indian National Congress Originated in 1885 A.D.At That Time,The Leaders of the Indian National Congres

History & Civics The Indian National Congress originated in 1885 A.D.At that time,the leaders of the Indian National Congress were the Moderates.But during the rule of Lord Curzon due to repressive policy of the British,the differences were created among the leaders of the INC.A group of leaders came into existence who did not believe in sympathy and justice of the British Government in India.They were called the Assertive Nationalists.Lala Lajpat Rai,Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Bipin Chandra Pal were the main leaders of the Assertives. Objectives:Achievement of Swaraj,Disestablishment of the relations between India and England.The Assertive Nationalist used self reliance and self sacrifice,sufferings and hardships for achieving their aim. The Early Nationalists did not fully approve the resolutions passed by the Assertive Nationalist in 1906,as a result this led to a split in the Congress in 1907. Bal Gangadhar Tilak:He was also known as Lokmanya.He organized Akharas and Lathi Clubs.His famous slogan was ‘Swaraj is my birthright and I will have it’.Through the Ganapati festival and revival of Shivaji festival in Maharashtra he installed a spirit of glory and patriotism. Bipin Chandra Pal:He was a great supporter of National Education.He opposed the partition of Bengal by spreading the message of boycott,swadeshi and national education.He also championed the cause of women education and opposed caste system. Lala Lajpat Rai:He was influenced by Tilak’s philosophy.His courage and determination have earned him the title of ‘Sher-i-Punjab’.He is remembered for his patriotism,courage and revolutionary ideas. -

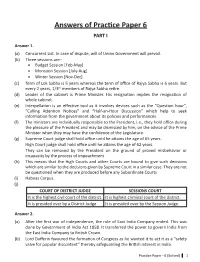

Checkpoint History Civics X Answers

Answers of Practice Paper 6 PART I Answer 1. (a) Concurrent List. In case of dispute, will of Union Government will prevail. (b) Three sessions are:- • Budget Session [Feb-May] • Monsoon Session [July-Aug] • Winter Session [Nov-Dec] (c) Term of Lok Sabha is 5 years whereas the term of office of Rajya Sabha is 6 years. But every 2 years, 1/3rd members of Rajya Sabha retire. (d) Leader of the cabinet is Prime Minister. His resignation implies the resignation of whole cabinet. (e) Interpellation is an effective tool as it involves devices such as the “Question hour”, “Calling Attention Notices” and “Half-an-Hour Discussion” which help to seek information from the government about its policies and performances. (f) The ministers are individually responsible to the President, i.e., they hold office during the pleasure of the President and may be dismissed by him, on the advice of the Prime Minister when they may have the confidence of the Legislature. (g) Supreme Court judge shall hold office until he attains the age of 65 years. High Court judge shall hold office until he attains the age of 62 years. They can be removed by the President on the ground of proved misbehavior or incapacity by the process of impeachment. (h) This means that the High Courts and other Courts are bound to give such decisions which are similar to the decisions given by Supreme Court in a similar case. They are not be questioned when they are produced before any Subordinate Courts. (i) Habeas Corpus. (j) COURT OF DISTRICT JUDGE SESSIONS COURT It is the highest civil court of the district. -

Women's Participation in Nationalist Movement : Moderate Phase. Personal Details Role Name Affiliation Principal Investigator Prof

Description of Module Subject Name Women’s Studies Paper Name Women’s Studies as an Academic Discipline Module Name/Title Women’s Participation in Nationalist Movement: Moderate Phase Module Id Pre-requisites The Reader is expected to have the knowledge of British Colonialism and Indian freedom struggle Objectives To make the reader understand the condition of Indian women, their issues and participation in public life Keywords Nationalist Movement, Indian National Congress, Moderates, Women Participation Women's Participation in Nationalist Movement : Moderate Phase. Personal Details Role Name Affiliation Principal Investigator Prof. Sumita Allahabad University, Allahabad Parmar Paper Coordinator Prof Chandrakala Chairperson ,IIAS, Shimla, Ex. Vice Padia Chancellor MGS University, Bikaner & Professor of Political Science, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi Content Writer/Author Dr. Afreen Khan Assistant Professor (CW) Department of Political Science & Public Administration Dr Harisingh Gour Vishwavidyalaya (A Central University) Sagar, Madhya Pradesh Content Reviewer (CR) Prof Chandrakala Chairperson ,IIAS, Shimla, Ex. Vice Padia Chancellor MGS University, Bikaner & Professor of Political Science, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi Language Editor (LE) Prof Chandrakala Chairperson ,IIAS, Shimla, Ex. Vice Padia Chancellor MGS University, Bikaner & Professor of Political Science, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi 1 Women’s Participation in Nationalist Movement: Moderate Phase 1.1 Nationalist Movement of India 1.2 Foundation of Indian National Congress 1.3 Moderate Character of Indian National Congress 1.4 Women Participation in nationalist movement 1.5 Women’s Organizations and activists 1.6 Moderate Phase of Congress and Womens Participation 1.7 Conclusion 1.8 References 1.1 Nationalist Movement of India The national movement covered a time span of sixty two years starting with the birth of the Indian National Congress in 1885 up to 1947. -

UNIT 1 CONTEXT and EMERGENCE of Gandhian Philosophy GANDHIAN PHILOSOPHY

Context and Emergence of UNIT 1 CONTEXT AND EMERGENCE OF Gandhian Philosophy GANDHIAN PHILOSOPHY Contents 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Context 1.3 Gandhi in the Indian Political Arena 1.4 Emergence as an All India Leader 1.5 Let Us Sum Up 1.6 Key Words 1.7 Further Readings and References 1.0 OBJECTIVES Gandhi is widely recognized as the preeminent theorist of nonviolent civil disobedience, the leader of India’s successful campaign for national independence and an architect of modern Indian self-identity. He never wrote a comprehensive and systematic political or philosophical work in the mode of Thomas Hobbes or Hegel, and the pamphlets and books he did write are extremely diverse in topic: they include criticisms of modern civilization, the place of religion in human life, the meaning of non-violence, social and economic programmes and even health issues. These works are constructed upon a series of concepts (satyagraha, swaraj, sarvodaya) which Gandhi elaborates into thematic strands. The Unit aims to throw some light on the unique context and the advent of Gandhi into a national leader. The emergence of Gandhi played a pivotal role in the history of Indian Nationalism. He took the country by storm with his novel political ideologies centered on the cardinal principles of ahimsa and satyagraha. Armed with these ideological tools Gandhi shouldered critical responsibilities in the momentous events that finally led India to the path of freedom. The emergence of Gandhi, on the Indian political scenario was not the mere instance of another emerging new leader, but it was the rise of a whole new philosophy that permeated into every sphere of the Indian psyche. -

Rise of Congress Moderates

Rise of Congress Moderates: The Early Nationalists also known as the Moderates, were a group of political leaders in India active between 1885 and 1907. Their emergence marked the beginning of the organised national movement in India.Dome of the important moderate leaders were pherozeshah Mehta and Dadabhai Naoroji.[5] With members of the group drawn from educated middle-class professionals including lawyers, teachers and government officials, many of them were educated in England. They are known as "Early Nationalists" because they believed in demanding reforms while adopting constitutional and peaceful means to achieve their aims The Early Nationalists had full faith in the British sense of justice, fair play, honesty, and integrity while they believed that British rule was a boon for India .The Early Nationalists were staunch believers in open-minded and moderate politics. Their successors, the "Assertives", existed from 1905 to 1919 and were followed by nationalists of the Gandhian era, which existed from 1919 until Indian Independence in 1947. Origins of the name "Moderates" The first session of the Early Nationalists of India in 1885 Focusing on demands for reform, the Early Nationalists adopted a constitutional and peaceful approach to achieve their objectives. They remained friendly towards the British rulers but believed that Indians should have a proper and legitimate role in the government of the country. Although they asked for constitutional and other reforms within the framework of British rule, they had full faith in that nation's sense of justice and fair play.[11] They further believed that continuation of the British connection with India was in the interests of both countries. -

Beginning of Modern Nationalism in India

Beginning of Modern Nationalism in India Temporal Context: 1850s and onwards Geographical Context: Indian subcontinent particularly presidency areas of Madras, Bombay and Calcutta Social context: Indian renaissance, social reform movement created an atmosphere conducive for the development of Modern Nationalism Political context: The growth of Modern Nationalism in India was influenced by 1. The worldwide upsurge of the concepts of nationalism and right of self-determination initiated by the French Revolution. 2. Modernisation initiated by the British in India. 3. British imperialist policies in India. Factors responsible for the growth of modern nationalism in India 1. Understanding of Contradictions in Indian and Colonial Interests 2. Political, Administrative and Economic Unification of the Country: Modern means of transport and communication brought people, especially the leaders, from different regions together. This was important for the exchange of political ideas and for mobilisation and organisation of public opinion on political and economic issues. 3. Western Thought and Education: The introduction of a modern system of education afforded opportunities for assimilation of modern Western ideas. This, in turn, gave a new direction to Indian political thinking. The liberal and radical thought of European writers like Milton, Shelley, John Stuart Mill, Rousseau, Paine, Spencer and Voltaire helped many Indians imbibe modern rational, secular, democratic and nationalist ideas. 4. Role of Press and Literature: The second half of the nineteenth century saw an unprecedented growth of Indian-owned English and vernacular newspapers, despite numerous restrictions imposed on the press by the colonial rulers from time to time. The press while criticising official policies, on the one hand, urged the people to unite, on the other. -

M.A. Part - I History Paper - II (Option - E) Indian National Movement (1857 A.D to 1947 A.D.)

1 M.A. Part - I History Paper - II (Option - E) Indian National Movement (1857 A.D to 1947 A.D.) Objectives : To enable students to understand the factors leading to the rise of Nationalism. To enable students to understand Gandhiji, his movements and movements of other organizations and to understand the constitutional development and the rise of new forces. Modules 1. Historiography of the Indian National Movement a) Nationalist, Marxist and Subaltern Schools b) Cambridge School c) Revolt of 1857 2. Rise of Socio-Political Consciousness a) Growth of Western Education and its impact on Socio Religious Movement b) British Economic Policies and their Impacts c) The founding of Indian National Congress, its Policies and Programme 3. Growth of Nationalism a) Gandhiji and his Movements b) All India Muslim League c) Hindu Mahasabha and Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh 2 4. Towards Independence a) Constitutional Developments b) Indian National Army, Naval Mutiny of 1946, Freedom and Partition c) The Depressed Classes and Women as New Forces Bibliography : K. Majumdar, Advent of Independence, Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan, Mumbai, 1969. R. Desai, Social Background of Indian Nationalism, 5th edition. Popular Prakashan, Mumbai, 1976. Anil Seal, The Emergence of Indian Nationalism : Competition and Collaboration in the Later Nineteenth Century, Cambridge University Press, 1971. Arvind Ganachari, Nationalism and Social Reform in a Colonial Situation, Kalpaz Publication New Delhi, 2005. R. Nanda (ed), Gokhale : The Indian Moderates and the British Raj, Princeton University Press, New Jerssy, 1977. Bimal Malhotra, Reform Reaction and nationalism, in Western India, 1855-190, Himalaya Publishing House, 2000. Bipin Chandra, The Rise and Growth of Economic Nationalism, in Western India, Economic Policies of the Indian National Leadership, 1850-1905 Peoples Publishing House, New Delhi, 1977. -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

"THE ROUTE TO YOUR ROOTS": HISTORY, HINDU NATIONALISM, AND COMICS IN INDIA AND SOUTH ASIAN DIASPORAS SAILAJA VATSALA KRISHNAMURTI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN SOCIAL & POLITICAL THOUGHT YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO MAY 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-39020-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-39020-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

National Movement - the Early Phase

11 National Movement - The Early Phase CHAPTER A 1885-1919 The National Movement in India forms British rule and fight to end it. This was the an important epoch in history as it helped beginning of the national movement in Fig 11A.1 : to weld diverse people and sections of India. Meeting at Surat society into one nation. All sections came The seeds of new consciousness began together to not only fight against the British in the second half of the 19 th century. The rule but also to build a new country. educated Indians after studying the nature Early Associations of the British rule and its impact on India became more and more critical of the In Class VII you have read about the British policies in India. They began to get consciousness and a key feature of (INC) at Bombay in December 1885. It revolt of 1857 in which the soldiers, together and discuss these issues and also nationalism. In other words, they believed was presided over by W. C. Banerjee and ordinary peasants, artisans and landlords formed associations for this. In 1866, that the Indian people should be attended by 72 delegates from different and even princes joined the struggle against Dadabhai Naoroji organized the “East India empowered to take decisions regarding the British rule. While the movement was parts of India. The early leaders – Dadabhai Association” in London to discuss the their affairs. Many of these intellectuals opposed to the British, it did not have any Nouroji, Pherozeshah Mehta, Badruddin Indian question. During 1866 to 1885, also led campaigns against some British new vision of the country. -

Dadabhai Naoroji and the Evolution of the Demand for Indian Self-Government

The Grand Old Man: Dadabhai Naoroji and the Evolution of the Demand for Indian Self-Government The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Patel, Dinyar Phiroze. 2015. The Grand Old Man: Dadabhai Naoroji and the Evolution of the Demand for Indian Self-Government. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17467241 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Grand Old Man: Dadabhai Naoroji and the Evolution of the Demand for Indian Self-Government A dissertation presented by Dinyar Patel to The Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 Dinyar Patel All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Sugata Bose Dinyar Patel The Grand Old Man: Dadabhai Naoroji and the Evolution of the Demand for Indian Self-Government Abstract This dissertation traces the thought and career of Dadabhai Naoroji, arguably the most significant Indian nationalist leader in the pre-Gandhian era. Naoroji (1825-1917) gave the Indian National Congress a tangible political goal in 1906 when he declared its objective to be self-government or swaraj. I identify three distinct phases in the development of his political thought.