Resistance Or Acceptance? the Voice of Local Cross-Border Organizations in Times of Re- Bordering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

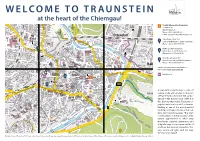

Welcome to Traunstein

r. S t tr c S rs traße h f- ue e s u rf a ß ß O n e a ol l l- K e r F L s ar hS ß t h r S u t r c c C e s a c d r a h w a i E i r Z S u l s t i ß le a s r s g e e ep . t r e c - Ka tr s l s h T n ns ra . il . lle n - Sc h b h hl e ß c S o ß ßs o e Z t a S n t ra r s A B ße r C r D E F G H I J K m e e t a u t t r . e m . s c a n aß e h tr e d - n s i ß S eder Su .- s i E t Fl R S S r t i o . r fs c l o r h a o t h d r e s g K s a Hurt n c e e w ß w r ß S K n n r e e e e me e h B ir s lu i c g c P t B s a a h fa r s Z c b r . t h e r r m e rg h a a ß o i a Zweckham str. R ß e tr Partenhausen f e a rs s s a bu t g t if ß m r. -

Daten Und Fakten

Chiemgau Tourismus e.V. Claudia Kreier Stadtplatz 32 D-83278 Traunstein Tel.: +49(0)861 909590-15 Fax: +49(0)861 909590-20 [email protected] www.chiemsee-chiemgau.info/presse Daten und Fakten Stand März 2021 Der Chiemgau ist eine historisch-kulturell gewachsene Landschaft im Süd- osten Bayerns mit dem Chiemsee im Zentrum und einer Größe von rund 2500 Quadratkilometern. Der Name Chiemgau ist seit dem 8. Jahrhundert belegt. Nicht-Einheimische bestehen gerne auf „das Chiemgau“, weil das Gau eine landschaftliche Einheit bezeichnet. Womöglich hat sich der Name Chiemgau aber auch vor Jahrhunderten von der „schönen Au bei Chieming“ abgeleitet – was für „die Chiemg-au“ spräche. Bei den Einheimischen heißt es jedoch un- verrückbar „der Chiemgau“. Namensgebend für Chieming wiederum war ein Gaugraf namens „Chiemo“ (um 744). Nach dem Verständnis des Bayerischen Landesamtes für Umwelt sind die Grenzen der historisch gewachsenen Region Chiemgau wie folgt: im Wes- ten der Inn, im Süden die österreichische Staatsgrenze, Osten der Rupertiwin- kel, im Norden das Alz-Hügelland. Demnach reicht der Chiemgau im Westen bis Rosenheim. (Geschichtliche Entwicklung siehe Seite 5.) Die nachfolgenden Zahlen und Daten gelten explizit für das Verbandsge- biet von Chiemgau Tourismus e.V., den Landkreis Traunstein. Touristische Basiszahlen Übernachtungen 2019: 4,282 Millionen Übernachtungen 2020: 4,049 Millionen Gäste 2019: 933.112 Gäste 2020: 777.122 (Hotels, Pensionen, Urlaub auf dem Bauernhof, Privatvermieter, Camping, Reha-Kliniken, gewerblich + privat) -

Rebuilding the Soul: Churches and Religion in Bavaria, 1945-1960

REBUILDING THE SOUL: CHURCHES AND RELIGION IN BAVARIA, 1945-1960 _________________________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _________________________________________________ by JOEL DAVIS Dr. Jonathan Sperber, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2007 © Copyright by Joel Davis 2007 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled REBUILDING THE SOUL: CHURCHES AND RELIGION IN BAVARIA, 1945-1960 presented by Joel Davis, a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. __________________________________ Prof. Jonathan Sperber __________________________________ Prof. John Frymire __________________________________ Prof. Richard Bienvenu __________________________________ Prof. John Wigger __________________________________ Prof. Roger Cook ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe thanks to a number of individuals and institutions whose help, guidance, support, and friendship made the research and writing of this dissertation possible. Two grants from the German Academic Exchange Service allowed me to spend considerable time in Germany. The first enabled me to attend a summer seminar at the Universität Regensburg. This experience greatly improved my German language skills and kindled my deep love of Bavaria. The second allowed me to spend a year in various archives throughout Bavaria collecting the raw material that serves as the basis for this dissertation. For this support, I am eternally grateful. The generosity of the German Academic Exchange Service is matched only by that of the German Historical Institute. The GHI funded two short-term trips to Germany that proved critically important. -

Germany (Territory Under Allied Occupation, 1945-1955 : U.S

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt0b69r4qg No online items An Inventory of the Germany (Territory under Allied occupation, 1945-1955 : U.S. Zone) Office of Military Government for Bavaria. Kreis Traunstein records Processed by Lyalya Kharitonova. Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 2010 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. XX416 1 An Inventory of the Germany (Territory under Allied occupation, 1945-1955 : U.S. Zone) Office of Military Government for Bavaria. Kreis Traunstein records Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Processed by: Lyalya Kharitonova Date Completed: 2010 Encoded by: Machine-readable finding aid derived from MARC record by David Sun and Supriya Wronkiewicz. © 2010 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Title: Germany (Territory under Allied occupation, 1945-1955 : U.S. Zone) Office of Military Government for Bavaria. Kreis Traunstein records Dates: 1945-1948 Collection Number: XX416 Creator: Germany (Territory under Allied occupation, 1945-1955 : U.S. Zone) Office of Military Government for Bavaria. Kreis Traunstein. Collection Size: 13 manuscript boxes (5.2 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: The records of American administration of occupied Germany (U.S. Zone), Kreis Traunstein relating to civil administration, including problems of public health and safety, administration of justice, allocation of economic recourses, organization of labor, denazification, and disposition of displaced persons contain memoranda, reports, correspondence, and office files. The collection also presents annual administrative reports on civilian relief efforts for other districts in Bavaria. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Languages: English German Access Collection is open for research. -

Die Fibelgräber Der Frühmittelalterlichen Nekropole Von Petting (Oberbayern)

Bayerische Vorgeschichtsblätter 78, 2013, S. 205–234 Die Fibelgräber der frühmittelalterlichen Nekropole von Petting (Oberbayern) Brigitte Haas-Gebhard und Franz Weindauer, München Der Fundort Petting spielte in der Erforschung der früh- Fundgeschichte mittelalterlichen Siedlungsentwicklung Südbayerns bis- lang kaum eine Rolle. Grund dafür ist eine ausgespro- chen problematische Fundgeschichte, die dazu führte, Die Ausgrabung des frühmittelalterlichen Gräberfeldes dass das Gräberfeld im Rahmen einer archäologisch-his- von Petting wurde notwendig, weil das Areal als Bau- torischen Auswertung nur unzureichend zur Kenntnis gebiet ausgewiesen worden war. Da die Grundstücke genommen werden konnte. für den Bau von Einfamilienhäusern bereits vor der Grabung an verschiedene Bauherren verkauft worden waren, ergab sich aufgrund der in Bayern bestehenden Rechtslage der Fall, dass der Freistaat Bayern als Finder Lage und Ausgrabung (= Ausgräber) den hälftigen Anteil an allen Fundstücken erworben hatte. Die andere Hälfte des Fundanteiles lag dagegen in den Händen von insgesamt 19 Grundei- Der Ort Petting befindet sich etwa 1 km südlich des Süd- gentümern, mit denen Verhandlungen über den end- ufers des Waginger Sees (Abb. 1). Der Abstand zu den gültigen Verbleib der Funde zu führen waren. Diese nördlichsten Ausläufern der Berchtesgadener Alpen be- Situation war zugegebenermaßen nicht ganz einfach trägt rund 10 km, zur Salzach 8 km, bis Salzburg sind es und konnte erst nach mehreren Anläufen von der Ar- etwa 25 km und bis nach Waging am See 7 km. chäologischen Staatssammlung und dem Bayerischen Das Bayerische Landesamt für Denkmalpflege Landesamt für Denkmalpflege im Jahr 2010 gelöst wer- führte in den Jahren 1991 bis 1993 eine großflächige den. Nur Dank des Einsatzes des Ersten Bürgermeisters archäologische Grabung auf der Flur „Am Mühlfeld“ in von Petting, Karl Lanzinger, und seinen Mitarbeitern Petting durch. -

Fahrplan Timetable

FAHRPLAN TIMETABLE Maiergschwendt Blicken Vorderbrand 9532 9532 Freizeitpark Haßlberg Guglberger Au Dorflinie Ruhpolding 9532 9532 9532 9532 9532 Westernberg/Chiemgau Coaster Gstatter Au Brand 9532 RVO Oberbayernbus Mühlwinkl 9532 Schwimmbadstraße Wasen 9532 9532 9532 9532 Geiern 9532 DBRuhpolding-Traunstein Bärngschwendt Unternberg- Bibelöd-Bahnhof Reit im bahn Vita Alpina 9532 Winkl Chiemgau-Arena 9532 Parkplatz Zentrum / Edeka Linie Biathlonzentrum Fritz Zug 9506 Weitsee Lödensee am Sand Fuchsau Eisenärzt Train Bahnhof DB Seegatterl Mittersee Seehaus Laubau Hinterpoint Schwaig Bibelöd Siegsdorf Traunstein Ortnerhof/ Bojernsteg M’bacher Str. Campingplatz Fischerwirt 9533 9533 9533 9533 9533 Egglbrücke Im Speck Vorder- Grashof St. Valentin Pennymarkt Chiemgau-Arena miesenbach Biathlonzentrum Ortnerhof/ 9533 9533 9533 9533 St. Valentin 9533 Campingplatz Grashof Fischerwirt 9533 Laubau Hinterpoint 9533 Zell / aja-Resort 9533 9533 Dorflinie Fritz 9533 am Sand 9533 Rauschberg- Häusler/Infang RVO-Bus bahn Linie Zug | Train 9506 Gnaig LabenbachAschenau Schmelz Inzell Fahrplan gültig – Timetable valid 19.12.2020 – 02.05.2021| 12.12.2020 – 11.04.2021 Dorflinie Ruhpolding | Local town bus - täglich | daily Linie 9533: Gültig vom| valid from 19.12.2020 - 02.05.2021 Egglbrücke - Im Speck -St. Valentin - Zell - Rauschberg - Laubau - Chiemgau Arena - Ortnerhof kk Linie 9533 Regionalbahn Traunstein - Ruhpoldingan 08:10 09:08 09:42 09:42 11:42 Bahnhof Ruhpolding ab 08:45 09:15 09:45 10:20 11:50 Egglbrücke / Pennymarkt 08:47 09:17 09:47 10:22 11:52 -

Exposé Reit Im Winkl

BAYERISCHE STAATSFORSTEN • AöR Telefon +49-8663-8887-0 Forstbetrieb Ruhpolding Telefax +49-8663-8887-20 [email protected] • www.baysf.de Exposé ehemaliges Forsthaus Weitseestraße 48, 83242 Reit im Winkl Mit der Verwertung dieses Grundstücks ist betraut: Mit der Vermarktung dieses Objektes betraut ist: Forstbetrieb Ruhpolding Zellerstraße 10 83324 Ruhpolding Herr Josef Kreuz Tel.: 08663 – 8887-0 Fax: 08663 – 8887-20 [email protected] Bayerische Staatsforsten AöR – Forstbetrieb Ruhpolding Zellerstraße 10, 83324 Ruhpolding Seite 1 von 16 BAYERISCHE STAATSFORSTEN • AöR Telefon +49-8663-8887-0 Forstbetrieb Ruhpolding Telefax +49-8663-8887-20 [email protected] • www.baysf.de 83242 Reit im Winkl, Weitseestraße 48 Ehem. Forstamtsanwesen Objektart: Freistehendes Wohnhaus mit Nebengebäuden Grundstück: FlNr. 818, Gemarkung Reit im Winkl zu 1.960 m² Grundbuchstand: Keine Belastung Grundstücks- und Gebäudebeschreibung: Bebauung: Wohngebäude, Gebäude- und Freifläche Planungs- und Liegt nicht im Geltungsbereich eines Baurecht: Bebauungsplans. Erschließung: Erfolgt bisher über das Nachbargrundstück FlNr. 121/11, Gemarkung Reit im Winkl Baujahr des Gebäudes: 1925 Denkmalschutz: nein Die Vergabe des Grundstücks erfolgt im Wege eines Erbbaurechts. Schriftliche Angebote werden bis zum 21.05.2021 um 12:00 Uhr in einem verschlossenen Kuvert mit dem Stichwort „Gebot Reit im Winkl“ erbeten. Objektbesichtigung nach telefonischer Vereinbarung. Ansprechpartner: Herr Josef Kreuz Tel.: 08663 – 8887 -0 Bayerische Staatsforsten AöR – Forstbetrieb Ruhpolding Zellerstraße 10, 83324 Ruhpolding Seite 2 von 16 BAYERISCHE STAATSFORSTEN • AöR Telefon +49-8663-8887-0 Forstbetrieb Ruhpolding Telefax +49-8663-8887-20 [email protected] • www.baysf.de 1. Standort 1.1 Makrolage Bundesland Bayern Regierungsbezirk Oberbayern Gemeinde Reit im Winkl, ca. 2.300 Einwohner Nächstgelegene Orte Kössen (Österreich), ca. -

Achental-Buslinie (Z.B

Linie 9 5 0 9 (Traunstein C) Grabenstätt C Wichtige Hinweise: Übersee C Grassau CStaudach CMarquartstein CUnterwössen CSchleching ( CReit im Winkl) Ö K L O A Liegt der Start oder das Ziel der Fahrt M T O E N Haltestellen S A F/S S,C A A C A A F S A ; A A ; A D E L L A C H außerhalb des Gebietes der Orte Ober- wössen, Unterwössen, Schleching, Traunstein Bahnhof ab 6.40 7.30 8.35 9.35 11.35 12.25 13.20 14.45 14.45 15.45 16.45 17.45 18.45 Kostenlose Staudach-Egerndach, Marquartstein, Grassau, Rottau, Grabenstätt und Übersee Erlstätt Ort 6.47 7.37 8.42 9.42 11.42 12.32 13.27 14.52 14.52 15.52 16.52 17.52 18.52 achental-buslinie (z.B. Prien, Traunstein, Reit im Winkl), wird Grabenstätt Marktplatz 6.54 7.44 8.49 9.49 11.49 12.39 13.34 14.59 14.59 15.59 16.59 17.59 18.59 ein ermäßigter Sonderpreis von € 4,- pro Schiff von Fraueninsel/Herreninsel (24.05.-21.09.2014) an Feldwies Dampfersteg (ca. 5 Min. Fussweg zur Bushaltestelle) 15.50 17.50 Sommer 2014 (Fahrplan gültig ab 01.05.2014) Person für Hin- und Rückfahrt berechnet. Feldwies Dampfersteg 16.05 18.05 Feldwies Abzweigung Autobahn 7.00 7.50 8.55 9.55 11.55 12.45 13.40 15.05 15.05 16.07 17.05 18.07 19.05 In Marquartstein, Haltestellenknoten „Rathaus“ besteht Umsteigemöglichkeit in Feldwies Abzweig. -

Announcement the Organizing Committee Would Like to Be Informed About the Time of Arrival and Departure (Incl

BOARD AND LODGING In accordance with ISU Communication No. 1752, paragraph 10.7, the Organizing Committee will cover room and meal expenses at the offi cial Hotel(s) for up to two (2) persons from each ISU Mem- ber with participating Competitors, beginning with dinner on the evening of Friday, February 08, 2013 and ending with breakfast on the morning of Monday, February 11, 2013 (See attachment for more information and hotel costs). HOTEL RESERVATION / OFFICIAL HOTEL(S) The Organizing Committee will make hotel reservation for the Competitors in the following hotels: Hotel Chiemgauer Hof Hotel Falkenstein Lärchenstraße 5 Kreuzfeldstraße 2 83334 Inzell / Germany 83334 Inzell / Germany Phone: 0049 (0) 8665 - 6700 Phone: 0049 (0) 8665 - 98890 Fax: 0049 (0) 8665 - 67070 Fax: 0049 (0) 8665 - 988965 [email protected] [email protected] Chiemgau Appartements Aparthotel Seidel Lärchenstraße 7 Lärchenstraße 17 83334 Inzell / Germany 83334 Inzell / Germany Phone: 0049 (0) 8665 - 6740 Phone: 0049 (0) 8665 - 98440 Fax: 0049 (0) 8665 - 674333 Fax: 0049 (0) 8665 - 984444 [email protected] [email protected] The Organizing Committee reserves the right to limit the number of hotel rooms available to each team at the of- fi cial hotel(s). The organizer is not obliged to provide services (accommodation, accredited entrance to the ice rink, transportation, etc.) for an excessive number of team offi cials or other accompanying persons from participating ISU Members. Names and functions of all team offi cials must be submitted together with the fi nal entries for the competition, in accordance with ISU Communication No. -

Thomas Bernhard and the “Air Crash“ on Tettelham in 1944.*

1 Michael Weithmann Thomas Bernhard and the “air crash“ on Tettelham in 1944.* “It was a spectacle of unrelieved tragedy.” The work of Thomas Bernhard (1931-1989), throughout his literary life controversial “negative state poet of Austria”, is not just marked by philanthropy and compassion. His autobiographical novel “A Child“ (“Ein Kind” 1982) is a sarcastic sequence of early experienced personal disappointments and injuries - interrupted only by warmhearted recollections of his grandfather Johann Freumbichler (1881-1949), a critical regional writer and therefore not very successful. There is one particular episode in his lifetime which stands out of the ordinary - not even Thomas Bernhard himself mentions an exact date – though, historic combinations resume it might have been in February 1944. Thomas Bernhard: “A Child“: From January 1938 to 1945, Bernhard lived in Traunstein, Upper Bavaria, together with his mother and his stepfather. Their dwelling in Schaumburgerstrasse 4 / corner Tauben- (Pigeon) market still exists. When moving from their former home in Seekirchen, Upper Austria, Thomas Bernhard was a child of only six years of age. In 2009, the city administration attached a memorial tablet at their house in Traunstein – an action, the author probably would have filled with smug wrath, were his Traunstein childhood years yet filled with humiliations in his parental home and at school! Only visiting his grandfather who lived close by in the village of Ettendorf kept him from committing suicide - provided that one gives real faith to his claims in “Ein Kind” (“A Child”). 2 “It was winter, cold as ice Thomas Bernhard remembers in that autobiographical story “Ein Kind”, when he sat with his grandmother in the Traunstein flat “in a marvellous, deep blue one Midday when the roar of a a bomber formation swelled: “The American planes, in formations of six, gleamed in the sky on their rigid course towards Munich. -

Seniorenwegweiser

Seniorenwegweiser Informationen Angebote Freizeit Adressen Ausgabe 2018 Ärzte/Apotheken Informationen Ärzte: Zahnärzte: Kirchen: Rathaus: Dr. med. dent. Hermann Katholische Kirche Lentner „Zum kostbaren Blut“ Marquartstein Lanzinger Str. 2 Loitshauser Str. 7 Rathausplatz 1 Allgemeinarzt Christoph Tel. 08641 / 75 26 Gottesdienste: 83250 Marquartstein Bader SO 10.00 Uhr Tel. 08641 / 69 95-0 Loitshauser Str. 33 A Dr. med. dent. Wolfgang Pfarrbüro: [email protected] Tel. 08641 / 83 33 Schwabe Unterer Mühlfeldweg 3 www.marquartstein.de Loitshauser Str. 18 Tel. 08641 / 82 19 Allgemeinarzt Tel. 08641 / 75 74 Dr. Christian Freund MO/DO 9.00 - 12.00 Uhr MO/DI/DO/FR 7.30 - 12.00 Lanzinger Str. 6 Zahnärztlicher Notdienst: DI 14.30 - 17.00 Uhr MI 9.00 - 12.00 Tel. 08641 / 61 387 Siehe Gemeindezeitung und 13.00 -17.30 Allgemeinärztin Apotheken: Evangelische Erlöserkirche Dr. med. Miriam v. Legat Loitshauser Str. 14 Tourist-Information: Pettendorfer Str. 1 Gottesdienste: MO-FR 8.30 - 12.00 Tel. 08641 / 97 88 0 SO 9.30 Uhr Achental Apotheke Pfarrbüro: Änderungen und zusätzliche - Pettendorfer Str. 1A Tel. 08641 / 84 07 Zeiten siehe Gemeindezei- dienst (24-Std.) Tel. 08641 / 69 72 77 Sprechzeiten: tung. Tel. 116 117 MO/DI/DO 9.00 - 10.30 Uhr Kannen Apotheke Alte Dorfstr. 7 Freundeskreis Diakonie Tel. 08641 / 8392 „Hilfe im Alltag“ Tel. 08641 / 78 10 Apothekennotdienst: Sprechzeiten: Siehe Gemeindezeitung Mo 18.00 - 19.00 Uhr Informationen Bildung Buslinien: Volkshochschulen: Paketdienste: Haltestelle vor dem Rathaus Volkshochschule Traunstein Volkshochschule Chiemsee Linie 9509: Fahrtrichtung Reit Stadtplatz 38a, Traunstein Hochfellnstr. 16, Prien im Winkl über Schleching und Tel. 0861 / 90 97 166-0 Tel. -

Chiemsee Radweg

Chiemsee Rundweg Wegstreckenangaben in Kilometer Chiemsee 1 : 50.000 Chiemseeringlinie Rad- und Wanderbus – RVO 9586 täglich von 3. Juni bis 8. Oktober 2017 Gäste mit Kurkarte fahren Fahrplan 2017 kostenlos! siehe Innenseite Chiemsee Rundweg Chiemsee Radweg www.chiemseeringlinie.de Chiemsee Radweg Tourentipps Wegstreckenangaben in Kilometer zur Chiemseeringlinie Neuauflage zum 10-jährigen Jubiläum! Die Broschüre „Rund um den Chiemsee – mit der Chiemseeringlinie wandern, radeln, Natur & Kultur erleben“ für 2,00 Euro ist auch im Bus der Chiemseeringlinie erhältlich. www.naturerlebnis-chiemsee.de 10 JAHRE CHIEMSEERINGLINIE Im Rahmen des Priener Marktfestes feiern wir das Jubiläum der Chiemseeringlinie! Am 13.08.2017 14.00 – 16.00 Uhr (Ausweichtermin 15.08.2017) Informationen zur Chiemsee-Region Chiemsee-Alpenland Tourismus www.chiemsee-alpenland.de • Tel. 08051 96 555 0 Felden 10 • 83233 Bernau am Chiemsee Chiemgau Tourismus e.V. www.chiemsee-chiemgau.info • Tel. 0861 909590 0 Haslacher Str. 30 • 83278 Traunstein Herausgeber: Chiemsee-Alpenland Tourismus GmbH & Co. KG, Felden 10, 83233 Bernau am Chiemsee, Tel. 08051 965550, Fax -30, [email protected], www.chiemsee-alpenland.de, Gestaltung: AZV Chiemsee/MBS, Chiemseeagenda/C. Linke, Karte: Kartographischer Verlag Huber GbR, 83088 Kiefersfelden, Fotos: Chiemsee-Alpenland Tourismus GmbH & Co. KG, Chiemgau Tourismus e.V., Chiemsee-Schifffahrt Ludwig Feßler KG, A. Hötzelsperger, A. Jacob, C. Linke, RVO/D. Bauer, J. Zimmermann, Druck: OrtmannTeam GmbH, 83404 Ainring, Auflage: 120.000, Stand: Dezember 2016, Irrtum und Änderungen vorbehalten. 161227/1p Lc Die Chiemseeringlinie – Fahrplan der Chiemseeringlinie für die Saison 2017 — vom 3. Juni bis 8. Oktober 2017 Die Chiemseeringlinie wird barrierefrei! einzigartig in Oberbayern Die Busse der Chiemseeringlinie sowie die meisten Haltestellen sind barrierefrei (zertifiziert im September 2016).