Thomas Bernhard and the “Air Crash“ on Tettelham in 1944.*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

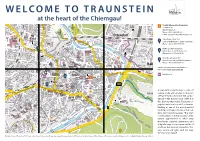

Welcome to Traunstein

r. S t tr c S rs traße h f- ue e s u rf a ß ß O n e a ol l l- K e r F L s ar hS ß t h r S u t r c c C e s a c d r a h w a i E i r Z S u l s t i ß le a s r s g e e ep . t r e c - Ka tr s l s h T n ns ra . il . lle n - Sc h b h hl e ß c S o ß ßs o e Z t a S n t ra r s A B ße r C r D E F G H I J K m e e t a u t t r . e m . s c a n aß e h tr e d - n s i ß S eder Su .- s i E t Fl R S S r t i o . r fs c l o r h a o t h d r e s g K s a Hurt n c e e w ß w r ß S K n n r e e e e me e h B ir s lu i c g c P t B s a a h fa r s Z c b r . t h e r r m e rg h a a ß o i a Zweckham str. R ß e tr Partenhausen f e a rs s s a bu t g t if ß m r. -

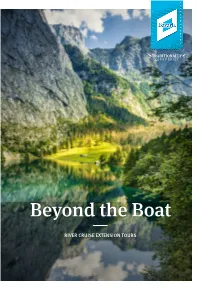

Beyond the Boat

Beyond the Boat RIVER CRUISE EXTENSION TOURS Welcome! We know the gift of travel is a valuable experience that connects people and places in many special ways. When tourism closed its doors during the difficult months of the COVID-19 outbreak, Germany ranked as the second safest country in the world by the London Deep Knowled- ge Group, furthering its trust as a destination. When you are ready to explore, river cruises continue to be a great way of traveling around Germany and this handy brochure provides tour ideas for those looking to venture beyond the boat or plan a stand-alone dream trip to Bavaria. The special tips inside capture the spirit of Bavaria – traditio- nally different and full of surprises. Safe travel planning! bavaria.by/rivercruise facebook.com/visitbavaria instagram.com/bayern Post your Bavarian experiences at #visitbavaria. Feel free to contact our US-based Bavaria expert Diana Gonzalez: [email protected] TIP: Stay up to date with our trade newsletter. Register at: bavaria.by/newsletter Publisher: Photos: p. 1: istock – bkindler | p. 2: BayTM – Peter von Felbert, Gert Krautbauer | p. 3: BayTM – Peter von Felbert, fotolia – BAYERN TOURISMUS herculaneum79 | p. 4/5: BayTM – Peter von Felbert | p. 6: BayTM – Gert Krautbauer | p. 7: BayTM – Peter von Felbert, Gert Kraut- Marketing GmbH bauer (2), Gregor Lengler, Florian Trykowski (2), Burg Rabenstein | p. 8: BayTM – Gert Krautbauer | p. 9: FC Bayern München, Arabellastr. 17 Burg Rabenstein, fotolia – atira | p. 10: BayTM – Peter von Felbert | p. 11: Käthe Wohlfahrt | p. 12: BayTM – Jan Greune, Gert Kraut- 81925 Munich, Germany bauer | p. -

Freizeit- Und Bildungsprogramm

August 2016 bis Januar 2017 Freizeit- und Bildungsprogramm für Menschen mit und ohne Behinderung und deren Angehörige Fotos v.li.o.: pixelio.de: Bernd von Dahlen, Joujou, www.reisen-sehenswuerdigkeiten.de, Sturm Joujou, Rainer Lanznaster, Dahlen, Maria von Bernd pixelio.de: v.li.o.: Fotos 02 Seite Seite 03 03 Vorwort Monatliches Programm Liebe Leser, liebe Nutzer, 04 Organisatorisches 15 • August 05 Geschäfts-Bedingungen / 23 • September Sie halten unser Freizeit- und Bildungsheft Wie wäre es mit der zweitägigen Fahrt in Zeichenerklärung 31 • Oktober mit weiteren Überraschungen in der Hand. den Bayerischen Wald oder haben Sie Lust 40 • November Wir wollen Sie mit neuen Ideen und kreativen das neue Programm mit zu gestalten? Angebote 47 • Dezember Seiten begeistern. Dann ist die Presse-Werkstatt genau das 06 • Offene Treffs 51 • Januar 2017 Richtige ... Die Angebote in diesem Heft sind vielfältig 08 Erläuterung Gruppe/Werkstatt Mehrtägige Freizeiten und abwechslungsreich. Für ein schönes Viel Spaß beim Blättern und Gestalten 55 Fahrt in den Bayerischen Wald buntes Leben braucht es ein schönes buntes wünscht Ihnen Gruppen Programm! 09 • EM-Fieber 2016 56 Liebe & so Sachen Schöne Veranstaltungen freuen sich auf ihren Das Team der Offenen Hilfen 10 • Eishockey-Spiele Besuch und ihre Teilnahme. Neuburg-Schrobenhausen 11 • JuZe Schrobenhausen Geschäfts-Bedingungen 58 Betreuungskosten / Fahrtkosten Werkstatt 59 Reisen: Kosten / Abmeldung Wir sind auf facebook Freizeit-Sprechstunde 12 • Basteln in Neuburg 60 Kontakt jeden Donnerstag 13 • Presse-Werkstatt -

Daten Und Fakten

Chiemgau Tourismus e.V. Claudia Kreier Stadtplatz 32 D-83278 Traunstein Tel.: +49(0)861 909590-15 Fax: +49(0)861 909590-20 [email protected] www.chiemsee-chiemgau.info/presse Daten und Fakten Stand März 2021 Der Chiemgau ist eine historisch-kulturell gewachsene Landschaft im Süd- osten Bayerns mit dem Chiemsee im Zentrum und einer Größe von rund 2500 Quadratkilometern. Der Name Chiemgau ist seit dem 8. Jahrhundert belegt. Nicht-Einheimische bestehen gerne auf „das Chiemgau“, weil das Gau eine landschaftliche Einheit bezeichnet. Womöglich hat sich der Name Chiemgau aber auch vor Jahrhunderten von der „schönen Au bei Chieming“ abgeleitet – was für „die Chiemg-au“ spräche. Bei den Einheimischen heißt es jedoch un- verrückbar „der Chiemgau“. Namensgebend für Chieming wiederum war ein Gaugraf namens „Chiemo“ (um 744). Nach dem Verständnis des Bayerischen Landesamtes für Umwelt sind die Grenzen der historisch gewachsenen Region Chiemgau wie folgt: im Wes- ten der Inn, im Süden die österreichische Staatsgrenze, Osten der Rupertiwin- kel, im Norden das Alz-Hügelland. Demnach reicht der Chiemgau im Westen bis Rosenheim. (Geschichtliche Entwicklung siehe Seite 5.) Die nachfolgenden Zahlen und Daten gelten explizit für das Verbandsge- biet von Chiemgau Tourismus e.V., den Landkreis Traunstein. Touristische Basiszahlen Übernachtungen 2019: 4,282 Millionen Übernachtungen 2020: 4,049 Millionen Gäste 2019: 933.112 Gäste 2020: 777.122 (Hotels, Pensionen, Urlaub auf dem Bauernhof, Privatvermieter, Camping, Reha-Kliniken, gewerblich + privat) -

Demographisches Profil Für Den Landkreis Ostallgäu

Beiträge zur Statistik Bayerns, Heft 553 Regionalisierte Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung für Bayern bis 2039 x Demographisches Profil für den xLandkreis Ostallgäu Hrsg. im Dezember 2020 Bestellnr. A182AB 202000 www.statistik.bayern.de/demographie Zeichenerklärung Auf- und Abrunden 0 mehr als nichts, aber weniger als die Hälfte der kleins- Im Allgemeinen ist ohne Rücksicht auf die Endsummen ten in der Tabelle nachgewiesenen Einheit auf- bzw. abgerundet worden. Deshalb können sich bei der Sum mierung von Einzelangaben geringfügige Ab- – nichts vorhanden oder keine Veränderung weichun gen zu den ausgewiesenen Endsummen ergeben. / keine Angaben, da Zahlen nicht sicher genug Bei der Aufglie derung der Gesamtheit in Prozent kann die Summe der Einzel werte wegen Rundens vom Wert 100 % · Zahlenwert unbekannt, geheimzuhalten oder nicht abweichen. Eine Abstimmung auf 100 % erfolgt im Allge- rechenbar meinen nicht. ... Angabe fällt später an X Tabellenfach gesperrt, da Aussage nicht sinnvoll ( ) Nachweis unter dem Vorbehalt, dass der Zahlenwert erhebliche Fehler aufweisen kann p vorläufiges Ergebnis r berichtigtes Ergebnis s geschätztes Ergebnis D Durchschnitt ‡ entspricht Publikationsservice Das Bayerische Landesamt für Statistik veröffentlicht jährlich über 400 Publikationen. Das aktuelle Veröffentlichungsverzeich- nis ist im Internet als Datei verfügbar, kann aber auch als Druckversion kostenlos zugesandt werden. Kostenlos Publikationsservice ist der Download der meisten Veröffentlichungen, z.B. von Alle Veröffentlichungen sind im Internet Statistischen -

Erlaubnis Zur Wasserrechtlichen Abteufung Von Bohrungen

Anzeige nach § 49 WHG i. V. m. Art. 30 des Bayerischen Wassergesetzes (BayWG ) für Bohrungen und Bodenaufschlüsse, die nur das erste, nicht gespannte Grundwasservorkommen erschließen bzw . Antrag auf wasserrechtliche Erlaubnis zur Abteufung von Bohrungen nach § 8 Wasserhaushaltsgesetz (WHG) Anlagen: Lageplan M 1 : 25.000 Lageplan M 1 : 1.000 (mit Bohrpunkten) voraussichtliches Bohrprofil mit Ausbauplanvorschlag Befreiung vom Anschluss- und Benutzungszwang des Trägers der öffentlichen Wasserversorgung (erforderlich bei Errichtung eines Brauchwasserbrunnens) Bestätigung des Wasserversorgers, dass kein Anschluss an die öff. Wasserversorgung vorliegt bzw. in absehbarer Zeit errichtet wird (erforderlich bei Trinkwasserbrunnen) Es werden folgende Arbeiten angezeigt: Die Arbeiten dienen folgendem späteren Zweck: Grundlagenermittlung, Beweissicherung o. ä. Versuchs-/Aufschlussbohrung Grundlagenermittlung für Bohrarbeiten Errichtung einer Grundwassermessstelle Grundwasserwärmepumpe Niederbringung einer Brunnenbohrung Grundwassermessstelle Verlegung von Flächenkollektoren Brauchwasserbrunnen Erdarbeiten im Grundwasserschwankungsbereich Trinkwasserbrunnen sonstige Aufschlüsse des Grundwassers Sonstiger Zweck:____________________________ Art:__________________________________________ Vorhabensträger Erreichbarkeit: Beauftragte Bohrfirma: Firma: Firma: Name: Tel.Nr.: Straße: Vorname: Fax-Nr.: PLZ, Ort: Straße: E-Mail: Tel.Nr.: PLZ: Ort: Fax-Nr.: Ort des Vorhabens Straße: PLZ/Ort: Fl.Nr.: Gemarkung: Gemeinde: Ortsteil: Das Grundstück liegt in einem -

Resistance Or Acceptance? the Voice of Local Cross-Border Organizations in Times of Re- Bordering

Journal of Borderlands Studies ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjbs20 Resistance or Acceptance? The Voice of Local Cross-Border Organizations in Times of Re- Bordering Sara Svensson To cite this article: Sara Svensson (2020): Resistance or Acceptance? The Voice of Local Cross-Border Organizations in Times of Re-Bordering, Journal of Borderlands Studies, DOI: 10.1080/08865655.2020.1787190 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2020.1787190 © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 03 Jul 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 38 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjbs20 JOURNAL OF BORDERLANDS STUDIES https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2020.1787190 Resistance or Acceptance? The Voice of Local Cross-Border Organizations in Times of Re-Bordering Sara Svensson a,b aEuropean University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, Florence, Italy; bSchool of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences, Halmstad University, Halmstad, Sweden ABSTRACT KEYWORDS National borders in Europe are increasingly subject to re-bordering Border control; cross-border processes, including the external and internal borders of the cooperation; refugee crisis; European Union. This article asks if and how local cross-border Euroregions; multi-level organizations (Euroregions) have reacted to to the recent governance hardening of these borders. The Austrian-German border is one where border controls have been re-introduced in the wake of the 2015 refugee crisis, and which also has significant local cross- border institutional activity. -

Collective Marketing of the Murnau Werdenfelser Cattle

WP 2 – Identification of Best Practices in the Collective Commercial Valorisation of Alpine Food ICH WP leader: Kedge Business School Activity A.T2.2 Field Study of Relevant Cases of Success: Collective Marketing of the Murnau Werdenfelser Cattle Involved partners: Florian Ortanderl Munich University of Applied Sciences This project is co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund through the Interreg Alpine Space programme. Abstract In Upper Bavaria, a network of farmers, butchers, restaurants, NGOs and a specially developed trade company cooperate in the safeguarding and valorisation of the endangered cattle breed Murnau Werdenfelser. The company MuWe Fleischhandels GmbH manages large parts of the value creation chain, from the butchering and packaging, to the distribution and marketing activities for the beef products. It pays the farmers a price premium and manages to achieve higher prices for both beef products and beef dishes in restaurants. The activities of the network significantly contributed to the safeguarding and livestock recovery of the endangered cattle breed. Kurzfassung In Oberbayern arbeitet ein Netzwerk aus Landwirten, Metzgern, Restaurants, NGOs und einem speziell dafür entwickelten Unternehmen an der Erhaltung und In-Wert-Setzung der bedrohten Rinderrasse Murnau-Werdenfelser. Das Unternehmen MuWe Fleischhandels GmbH organisiert große Teile der Wertschöpfungskette, von der Metzgerei und der Verpackung, bis zur Distribution und allen Marketing Aktivitäten für die Rindfleischprodukte. Es zahlt den Landwirten einen Preiszuschlag und erzielt Premiumpreise für die Rindfleischprodukte, als auch für Rindfleischgerichte in Restaurants. Die Aktivitäten des Netzwerks haben entscheidend zur Erhaltung und Erholung der Bestände der bedrohten Rinderrasse beigetragen. 1.1 Case typology and historical background This case report analyses a network-based marketing approach for beef products and dishes of the endangered Bavarian cattle breed Murnau Werdenfelser. -

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 As of December, 2009 Club Fam

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 as of December, 2009 Club Fam. Unit Fam. Unit Club Ttl. Club Ttl. District Number Club Name HH's 1/2 Dues Females Male TOTAL District 111BS 21847 AUGSBURG 0 0 0 35 35 District 111BS 21848 AUGSBURG RAETIA 0 0 1 49 50 District 111BS 21849 BAD REICHENHALL 0 0 2 25 27 District 111BS 21850 BAD TOELZ 0 0 0 36 36 District 111BS 21851 BAD WORISHOFEN MINDELHEIM 0 0 0 43 43 District 111BS 21852 PRIEN AM CHIEMSEE 0 0 0 36 36 District 111BS 21853 FREISING 0 0 0 48 48 District 111BS 21854 FRIEDRICHSHAFEN 0 0 0 43 43 District 111BS 21855 FUESSEN ALLGAEU 0 0 1 33 34 District 111BS 21856 GARMISCH PARTENKIRCHEN 0 0 0 45 45 District 111BS 21857 MUENCHEN GRUENWALD 0 0 1 43 44 District 111BS 21858 INGOLSTADT 0 0 0 62 62 District 111BS 21859 MUENCHEN ISARTAL 0 0 1 27 28 District 111BS 21860 KAUFBEUREN 0 0 0 33 33 District 111BS 21861 KEMPTEN ALLGAEU 0 0 0 45 45 District 111BS 21862 LANDSBERG AM LECH 0 0 1 36 37 District 111BS 21863 LINDAU 0 0 2 33 35 District 111BS 21864 MEMMINGEN 0 0 0 57 57 District 111BS 21865 MITTELSCHWABEN 0 0 0 42 42 District 111BS 21866 MITTENWALD 0 0 0 31 31 District 111BS 21867 MUENCHEN 0 0 0 35 35 District 111BS 21868 MUENCHEN ARABELLAPARK 0 0 0 32 32 District 111BS 21869 MUENCHEN-ALT-SCHWABING 0 0 0 34 34 District 111BS 21870 MUENCHEN BAVARIA 0 0 0 31 31 District 111BS 21871 MUENCHEN SOLLN 0 0 0 29 29 District 111BS 21872 MUENCHEN NYMPHENBURG 0 0 0 32 32 District 111BS 21873 MUENCHEN RESIDENZ 0 0 0 22 22 District 111BS 21874 MUENCHEN WUERMTAL 0 0 0 31 31 District 111BS 21875 -

Landkreis Freyung-Grafenau

DATENBLATT HANDEL Landkreis Freyung-Grafenau KAUFKRAFTSTROMANALYSE UND EINZELHANDELSUNTERSUCHUNG 2014 Die Ausführungen und Grafiken auf diesem Datenblatt Broschüre „Starke Handelszentren“, die die erarbeiteten basieren auf der in den Jahren 2013 und 2014 durch- Ergebnisse und wichtigsten Aussagen zusammenfasst. geführten Kaufkraftstrom- und Einzelhandelsstruktur- untersuchung Niederbayern-Oberösterreich, die von der Ein Vergleich zwischen diesen Standorten ist nicht IHK Niederbayern, der WKO Oberösterreich sowie vom immer sinnvoll, da das Auswahlkriterium für die Analyse Land Oberösterreich initiiert und mit EU-Mitteln aus der Einkaufsstandorte weniger eine vergleichbare Struk- dem INTERREG-Programm Bayern-Österreich (2007 - tur der Städte und Gemeinden war, sondern vielmehr die 2013) finanziert wurde. Es zeigt schlagwortartig Auszüge Nähe zum oberösterreichischen Grenzraum und damit zu von Handelskennzahlen in den drei Handelsstandorten den oberösterreichischen Konsument(inn)en. Freyung, Grafenau und Waldkirchen und untersetzt die Inhaltsverzeichnis Kaufkraft-Eigenbindung .............................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Kaufkraft-Zu- und Abflüsse – Landkreis Deggendorf ......................................................................................................................... 4 Verkaufsfläche pro Einwohner ................................................................................................................................................................. -

Rebuilding the Soul: Churches and Religion in Bavaria, 1945-1960

REBUILDING THE SOUL: CHURCHES AND RELIGION IN BAVARIA, 1945-1960 _________________________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _________________________________________________ by JOEL DAVIS Dr. Jonathan Sperber, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2007 © Copyright by Joel Davis 2007 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled REBUILDING THE SOUL: CHURCHES AND RELIGION IN BAVARIA, 1945-1960 presented by Joel Davis, a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. __________________________________ Prof. Jonathan Sperber __________________________________ Prof. John Frymire __________________________________ Prof. Richard Bienvenu __________________________________ Prof. John Wigger __________________________________ Prof. Roger Cook ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe thanks to a number of individuals and institutions whose help, guidance, support, and friendship made the research and writing of this dissertation possible. Two grants from the German Academic Exchange Service allowed me to spend considerable time in Germany. The first enabled me to attend a summer seminar at the Universität Regensburg. This experience greatly improved my German language skills and kindled my deep love of Bavaria. The second allowed me to spend a year in various archives throughout Bavaria collecting the raw material that serves as the basis for this dissertation. For this support, I am eternally grateful. The generosity of the German Academic Exchange Service is matched only by that of the German Historical Institute. The GHI funded two short-term trips to Germany that proved critically important. -

Allgemeinverfügung Des Landratsamtes Garmisch-Partenkirchen Vom 16.06.2006 – Abt

A M T S B L A T T FÜR DEN LANDKREIS TRAUNSTEIN Herausgegeben vom Landratsamt Traunstein Erscheint i. d. Regel wöchentlich Bezugspreis vierteljährlich 0,60 € zzgl. Porto Einzelpreis 0,05 € Zu beziehen unmittelbar beim Landratsamt Traunstein oder über die Gemeindeverwaltungen Nr. 25 83278 Traunstein, den 23. Juni 2006 Seite 123 Inhaltsverzeichnis: Sitzung des Jugendhilfeausschusses 66/25 Allgemeinverfügung des Landratsamtes Garmisch-Partenkirchen vom 16.06.2006 – Abt. 5 – im Fall des Braunbären „JJ1“; 67/25 Allgemeinverfügung des Landratsamtes Garmisch-Partenkirchen vom 16.06.2006 – Abt. 5 – im Fall des Braunbären „JJ1“; 68/25 Seite 124 Amtsblatt für den Landkreis Traunstein Nr. 25 ............................................................................................................................................................................................................ 66/06 23-421/111 Sitzung des Jugendhilfeausschusses gemäß §§ 70 Abs. 1 und 71 Abs. 2 SGB VIII sowie § 6 Abs. 7 der Satzung für das Amt für Kinder, Jugend und Familie des Landkreises Traunstein habe ich den Jugendhilfeausschuss für Dienstag, den 27.06.2006, 9.00 Uhr zu einer ordentlichen Sitzung eingeladen. Tagesordnung: TOP 1 Kreisjugendring Traunstein – Grundlagenvertrag – TOP 2 Raumvorgaben für Kindertageseinrichtungen TOP 3 Richtlinien für Vollzeit- und Tagespflege TOP 4 Kooperation zwischen Jugendhilfe und Suchthilfe TOP 5 Jugendsozialarbeit an Schulen TOP 6 Bericht über das Mütterzentrum Traunstein TOP 7 Verschiedenes/Wünsche/Anträge Georg Klausner Stellvertreter des Landrats --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 67/06 SG 35-B 131/1-1 Allgemeinverfügung des Landratsamtes Garmisch-Partenkirchen vom 13.06.2006 – Abt. 5 - bezüglich des Suchens, des Stellens, des Fangens und des Tötens des Braunbären „JJ1“; Das Landratsamt Garmisch-Partenkirchen hat am 13.06.2006 – Az.: Abt. 5 - u. a. auch für den Bereich des Landkreises Traunstein folgende Allgemeinverfügung erlassen: Allgemeinverfügung: 1.