1 Genewatch UK Response to the Nuffield Council on Bioethics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A DNA Database in the NHS: Your Freedom up for Sale?

A DNA database in the NHS: Your freedom up for sale? May 2013 In April 2013, the Caldicott Committee, including Government Chief Scientist Sir Mark Walport, proposed new rules for data-sharing which would allow the Government to build a DNA database of the whole population of England in the NHS by stealth.1 The plan is to make NHS medical records and people’s genetic information available to commercial companies and to use public-private partnerships to build a system where all private information about every citizen is also accessible to the police, social workers, security services and Government. The Wellcome Trust, which was involved in the Human Genome Project and was led by Walport for ten years, has produced a plan which involves including a variant file, containing the whole genome of every person minus the reference genome, as an attachment to every medical record in the NHS in England.2 This data would be made available to ‘researchers’ (including commercial companies) for data-mining in the cloud and personalised risk assessments would be returned to individuals. The aim is to transform the NHS in line with proposals developed more than a decade ago by former GlaxoSmithKline Chairman Sir Richard Sykes. This is expected to massively expand the market for medicines, medical tests and other products, such as supplements and cholesterol-lowering margarines, by allowing products to be marketed to individuals based on personal risk assessments, created using statistical analysis of genetic data, medical records and other health information. The proposal to build a DNA database in the NHS was endorsed by the Human Genomics Strategy Group in 20123,4 and the Government (led by Prime Minister David Cameron) has quietly adopted this recommendation without telling members of the public. -

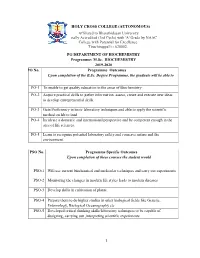

2019-2020 PO No

HOLY CROSS COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) Affiliated to Bharathidasan University Nationally Accredited (3rd Cycle) with 'A' Grade by NAAC College with Potential for Excellence. Tiruchirappalli - 620002. PG DEPARTMENT OF BIOCHEMISTRY Programme: M.Sc. BIOCHEMISTRY 2019-2020 PO No. Programme Outcomes Upon completion of the B.Sc. Degree Programme, the graduate will be able to PO-1 To enable to get quality education in the areas of Biochemistry PO-2 Acquire practical skills to gather information, assess, create and execute new ideas to develop entrepreneurial skills. PO-3 Gain Proficiency in basic laboratory techniques and able to apply the scientific method on lab to land PO-4 Inculcate a domestic and international perspective and be competent enough in the area of life sciences. PO-5 Learn to recognize potential laboratory safety and conserve nature and the environment. PSO No. Programme Specific Outcomes Upon completion of these courses the student would PSO-1 Will use current biochemical and molecular techniques and carry out experiments PSO-2 Monitoring the changes in modern life styles leads to modern diseases PSO-3 Develop skills in cultivation of plants. PSO-4 Prepare them to do higher studies in other biological fields like Genetic, Entomology, Biological Oceanography etc PSO-5 Developed critical thinking skills/laboratory techniques to be capable of designing, carrying out ,interpreting scientific experiments 1 HOLY CROSS COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) PG DEPARTMENT OF BIOCHEMISTRY (Students admitted from the year 2018 onwards) M.Sc. Biochemistry-Course -

Wellcome Trust Annual Report and Financial Statements 2019 Is © the Wellcome Trust and Is Licensed Under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 UK

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2019 Table of contents Report from Chair 3 Report from Director 5 Trustee’s Report 7 What we do 8 Review of Charitable Activities 9 Review of Investment Activities 21 Financial Review 31 Structure and Governance 36 Social Responsibility 40 Risk Management 42 Remuneration Report 44 Remuneration Committee Report 46 Nomination Committee Report 47 Investment Committee Report 48 Audit and Risk Committee Report 49 Independent Auditor’s Report 52 Financial Statements 61 Consolidated Statement of Financial Activities 62 Consolidated Balance Sheet 63 Statement of Financial Activities of the Trust 64 Balance Sheet of the Trust 65 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 66 Notes to the Financial Statements 67 Alternative Performance Measures and Key Performance Indicators 114 Glossary of Terms 115 Reference and Administrative Details 116 Table of Contents Wellcome Trust Annual Report 2019 | 2 Report from Chair During my tenure at Wellcome, which ends in The macro environment is increasingly challenging, 2020, I count myself lucky to have had the which has created volatility in financial markets. opportunity to meet inspiring people from a rich Q4 2018 was a very difficult quarter, but the diversity of sectors, backgrounds, specialisms resumption of interest rate cuts by the US Federal and scientific fields. Reserve underpinned another year of gains for our portfolio. We recognise that the cycle is extended, Wellcome’s achievements belong to the people and that the portfolio is likely to face more who work here and to the people we fund – it is challenging times ahead. a partnership that continues to grow stronger, more influential and more ambitious, spurred by The team is working hard to ensure that our independence. -

OVER £140 Prime Minister, the Rt Hon David Came

PRIME MINISTER QUARTERLY INFORMATION: 1 APRIL – 30 JUNE 2011 GIFTS (RECEIVED) OVER £140 Prime Minister, The Rt Hon David Cameron MP Date gift From Gift Value Outcome received April 2011 Prime Minister of Furniture Over Held by Department Pakistan limit April 2011 Prime Minister of Rug Over Held by BHC Pakistan limit Islamabad April 2011 Italian Aeronautica Leather jacket Over Held by Department Militare limit April 2011 Portmeirion Potteries China Over Held by Department Group limit May 2011 President Obama and Silver jewellery and Over Held by Department Mrs Obama First Edition Book limit May 2011 President of Russia Painting Over Held by Department limit May 2011 President of France Pen Set and Over Held by Department Glassware limit June 2011 Prime Minister of Picture Over Held by Department Malaysia limit GIFTS (GIVEN) OVER £140 Prime Minister, The Rt Hon David Cameron MP Date gift From Gift Value Outcome given Nil return HOSPITALITY1 Prime Minister, The Rt Hon David Cameron MP Date Name of Organisation Type of Hospitality Received NIL RETURN 1 Does not normally include attendance at functions hosted by HM Government; ‘diplomatic’ functions in the UK or abroad, hosted by overseas governments; minor refreshments at meetings, receptions, conferences, and seminars; and offers of hospitality which were declined. OVERSEAS TRAVEL Prime Minister Date(s) of trip Destination Purpose of ‘No 32 (The Number of Total cost trip Royal) officials including travel Squadron’ accompanying and or ‘other Minister, where accommodation of RAF’ or non-scheduled -

Understanding the an English Agribusiness Lobby Group

Understanding the NFU an English Agribusiness Lobby Group Ethical Consumer Research Association December 2016 Understanding the NFU - an English Agribusiness Lobby-group ECRA December 2016 1 Contents 1. Introduction – The NFU an English Agribusiness Lobby group 3 2. Economic Lobbying – undermining the smaller farmer 2.1 NFU and farm subsidies – promoting agribusiness at the expense of smaller farmers 11 2.2 NFU and TTIP – favouring free trade at the expense of smaller farms 15 2.3 NFU and supermarkets – siding with retailers and opposing the GCA 17 2.4 NFU and foot and mouth disease – exports prioritised over smaller producers 20 3. Environmental Lobbying – unconcerned about sustainability 3.1 NFU, bees and neonicotinoids – risking it all for a few pence more per acre 24 3.2 NFU and soil erosion – opposing formal protection 28 3.3 NFU and air pollution – opposing EU regulation 31 3.4 NFU, biodiversity and meadows – keeping the regulations away 33 3.5 NFU and Europe – keeping sustainability out of the CAP 41 3/6 NFU and climate change – a mixed response 47 3.7 NFU and flooding – not listening to the experts? 51 4. Animal interventions – keeping protection to a minimum 4.1 Farm animal welfare – favouring the megafarm 53 4.2 NFU, badgers and bovine TB – driving a cull in the face of scientific evidence 60 4.3 The Red Tractor label – keeping standards low 74 5. Social Lobbying – passing costs on to the rest of us 5.1 NFU and Organophosphates in sheep dip – failing to protect farmers’ health 78 5.2 NFU and road safety – opposing regulations 82 5.3 NFU and workers’ rights – opposing the Agricultural Wages Board 86 5.4 NFU and Biotechnology – Supporting GM crops 89 6. -

Alagappa University M. Sc. Biotechnology

ANNEXURE I M. Sc., Biotechnology (Specialization: Marine Biotechnology) CBCS Course Structure & Syllabus (For those who joined in July 2011 or after) Department of Biotechnology (UGC-SAP and DST-FIST & PURSE Sponsored Department) Alagappa University (A State University Accredited with “A” Grade by NAAC) Karaikudi 630 003 1 DEPARTMENT OF BIOTECHNOLOGY (UGC-SAP and DST-FIST & PURSE Sponsored Department) ALAGAPPA UNIVERSITY (A State University Accredited with “A” Grade by NAAC) M. Sc., Biotechnology Programme Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) For those who joined in July 2011 or after Course Structure S. Code Name of the Course Credits Marks No SEMESTER – I Int. Ext. Total 1. 501101 Core 1: Biochemistry 4 25 75 100 2. 501102 Core 2: Microbiology 4 25 75 100 3. 501103 Core 3: Molecular Biology and Genetics 4 25 75 100 4. 501104 Core 4: Cell Biology 4 25 75 100 5. 501105 Core 5: Lab I: Analytical Biochemistry 4 25 75 100 6. 501106 Core 6: Lab II: Microbiology 4 25 75 100 7. Elective 1 5 25 75 100 29 175 525 700 SEMESTER – II Int. Ext. Total 8. 501201 Core 7: Immunobiology 4 25 75 100 9. 501202 Core 8: Recombinant DNA Technology 4 25 75 100 10. 501203 Core 9: Plant Molecular Biology 4 25 75 100 11. 501204 Core 10: Lab III: Molecular Genetics 4 25 75 100 12. 501205 Core 11:Lab IV: Immunotechnology 4 25 75 100 13. Elective 2 5 25 75 100 25 150 450 600 SEMESTER – III Int. Ext. Total 14. 501301 Core 12: Bioinformatics 4 25 75 100 15. -

LIST of CONFIRMED SPEAKERS 9Th FEBRUARY

SPEAKERS CONFIRMED AS OF FEBRUARY 9th 2011 - Françoise Barré-Sinoussi , Nobel Prize in Medicine 2008, Professor , Head of Unit of regulation of retroviral infections, Institut Pasteur, Paris, INSERM, France - Zhu Chen , Health Minister, People’s Republic of China - José Angel Cordoba Villalobos , Health Minister, Mexico - Jean-Marie Lehn , Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1987, Professor, University Louis Pasteur, France - Antonio Tajani , Vice president, European Commission, in charge of Industry and Entrepreneurship - Roger Tsien , Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2008, HHMI Investigator, Professor of Pharmacology and of Chemistry & Biochemistry, University of California, San Diego, USA - Ada Yonath , Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2009, Professor, Weizmann Institute, Israel - Bernard Bigot , Chairman and CEO, French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA), France - Luis Cantarell , President & CEO Nestlé Health Science S.A., Switzerland - Esther Duflo , Professor, MIT, USA - Catherine Geslain-Lanéelle , Executive Director, European Food Safety Authority - Unni Karunakara , International President, MSF, Switzerland - Vishwa Mohan Katoch , Director, Indian Council of Medical Research - Michel Kazaktchkine , Executive Director, The Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria - Thomas Lönngren , Executive Director, European Medicines Agency (EMA) - Alain Mérieux , President, Institut Mérieux, France - Feike Sijbesma , CEO & Chairman Managing Board, Royal DSM NV, The Netherlands - Paul Stoffels, M.D., Worldwide Chairman, Janssen, Pharmaceutical -

Lstm Annual Report

LSTM ANNUAL REPORT 2019/20 2019/2020 Vision To save lives in resource poor countries through research, education and capacity strengthening Mission To reduce the burden of sickness and mortality in disease endemic countries through the delivery of effective interventions which improve human health and are relevant to the poorest communities Values • Making a difference to health and wellbeing • Excellence in innovation, leadership and science • Achieving and delivering through partnership • An ethical ethos founded on respect, accountability and honesty • Creating a great place to work and study 2 2019/2020 Contents Chair’s Foreword 4 Director’s Foreword 5 Treasurer’s Report 6 LSTM’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic 7 Introduction to the Feature Articles 14 FEATURE ARTICLE: Neglected Tropical Diseases 15 Department of Tropical Disease Biology 19 FEATURE ARTICLE: Malaria and other Vector Borne Diseases 22 Department of Vector Biology 26 FEATURE ARTICLE: Resistance Research and Management 28 Department of Clinical Sciences 30 FEATURE ARTICLE: Lung Health and TB 33 Department of International Public Health 36 FEATURE ARTICLE: HIV 39 Partnerships 41 FEATURE ARTICLE: Maternal, Newborn and Child Health 46 Public Engagement 50 FEATURE ARTICLE: Innovations, Discovery and Development 51 Going Virtual 54 FEATURE ARTICLE: Health Policy and Health Systems Research 56 Finance, Procurement and Research Services (FPRS) 59 Education 60 Research Governance and Ethics 62 Clinical Diagnostic Parasitology Laboratory (CDPL) 64 Well Travelled Clinics 65 Liverpool Insect Testing Establishment (LITE) 66 IVCC 67 Far East Prisoners of War (FEPOW) 68 LSTM in the Media 69 Fundraising 70 Estates 71 People and Culture 73 Staff Overview 75 Governance and Business Continuity Management 76 Officers 2019/20 77 Awards and Honours 78 Lectures and Seminars 79 Publications 80 LSTM Pioneers 81 Research Consortia Hosted and Managed by LSTM 82 Public Benefit Statement 84 Opposite page: An IMPROVE trial participant checks on her sleeping child under a bednet in western Kenya. -

Wellcome Trust Joins 'Academic Spring' to Open up Science

Printing sponsored by: Wellcome Trust joins 'academic spring' to open up science Wellcome backs campaign to break stranglehold of academic journals and allow all research papers to be shared free online Alok Jha, science correspondent guardian.co.uk, Monday 9 April 2012 20.44 BST larger | smaller Article history Wellcome's move adds weight to the campaign for open access to academic knowledge, which could lead to benefits across a broad range of research fields. Photograph: Mauricio Lima/AFP/Getty Images One of the world's largest funders of science is to throw its weight behind a growing campaign to break the stranglehold of academic journals and allow all research papers to be shared online. Nearly 9,000 researchers have already signed up to a boycott of journals that restrict free sharing as part of a campaign dubbed the "academic spring" by supporters due to its potential for revolutionising the spread of knowledge. But the intervention of the Wellcome Trust, the largest non-governmental funder of medical research after the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, is likely to galvanise the movement by forcing academics it funds to publish in open online journals. Sir Mark Walport, the director of Wellcome Trust, said that his organisation is in the final stages of launching a high calibre scientific journal called eLife that would compete directly with top-tier publications such as Nature and Science, seen by scientists as the premier locations for publishing. Unlike traditional journals, however, which cost British universities hundreds of millions of pounds a year to access, articles in eLife will be free to view on the web as soon as they are published. -

All-Party Parliamentary Group on Medical Research Summer Reception

All-Party Parliamentary Group on Medical Research Summer Reception Showcasing UK medical research – working together for patients, society and the economy 19 July 2010 The All-Party Parliamentary Group on Medical Research includes MPs and peers from across the political parties. Established in December 2005, it provides a network for Parliamentarians with an interest in the medical research sector. The APPG is supported by the Medical Research Council (MRC), The Academy of Medical Sciences (AMS), the Association of Medical Research Charities (AMRC), Cancer Research UK, and the Wellcome Trust. The theme of this year’s Summer Reception is the lifecycle of medical research, from underpinning science to clinical practice, encompassing epidemiology, applied and translational research, influencing policy and supporting infrastructure projects. Researchers from across the country are coming together in Parliament to talk about how they are working together to develop the drugs and treatments that will go on to transform patients’ lives. This will be a great opportunity to find out more about how they do this and where you, as Parliamentarians, can help. Event Programme Speakers: Lord Turnberg – Chair of the APPG on Medical Research David Willetts – Minister of State for Universities & Science Sir Mark Walport – Director of the Wellcome Trust Claire Daniels – cancer survivor Julian Huppert – MP for Cambridge and member of the APPG on Medical Research Cover image: a cluster of nerve cells called cerebellar granule cells, growing in culture. Ludovic Collin/Wellcome Images Welcome to the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Medical Research’s summer reception 2010. This is a critically important year for medical and health research. -

History of UK Biobank, Electronic Medical Records in the NHS, and the Proposal for Data-Sharing Without Consent

Bioscience for Life? Appendix A The history of UK Biobank, electronic medical records in the NHS, and the proposal for data-sharing without consent January 2009 1 Bioscience for Life? Appendix A Table of contents 1. Introduction................................................................... 12 2. Summary........................................................................ 12 3. What is UK Biobank?...................................................... 13 4. Concerns about UK Biobank and genetic ‘prediction and prevention’ of disease........................................................ 14 5. Timeline......................................................................... 15 1995................................................................................... 15 The Foresight report................................................................................ 15 1997................................................................................... 16 The biotech economy......................................................... 16 The European directive and gene patenting........................17 A new NHS........................................................................ 17 1998.................................................................................. 17 Claims that genetics will transform medicine.................... 17 The Government partners with the Wellcome Trust........... 18 The McKinsey Report......................................................... 18 An increasing role for the Wellcome Trust........................ -

Characterization of the Monocyte to Macrophage Differentiation (MMD) Protein and Its Homologue MMD2

Characterization of the Monocyte to Macrophage Differentiation (MMD) protein and its homologue MMD2 Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Naturwissenschaften (Dr.rer.nat.) der Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät III - Biologie und vorklinische Medizin der Universität Regensburg vorgelegt von Carol El Chartouni aus Beirut - Libanon Juni 2006 The work presented in this thesis was carried out in the Department of Hematology and Oncology at the University Hospital Regensburg from June 2002 to Februar 2006. Die vorliegende Arbeit entstand in der Zeit von Juni 2002 bis Februar 2005 in der Abteilung für Hämatologie und Internistische Onkologie des Klinikums der Universität Regensburg. Promotionsgesuch eingereicht am: 27.06.2006 Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 8.09.2006 Die Arbeit wurde angeleitet von: PD Dr. Michael Rehli - Prof. Dr. Stephan Schneuwly. Prüfungsausshuß: Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. Christoph Oberprieler 1. Prüfer (Erstgutachten): Prof: Dr. Stephan Schneuwly 2. Prüfer (Zweitgutachten): PD. Dr. Michael Rehli 3. Prüfer: Prof. Dr. Karl Kunzelmann Table of contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Mononuclear phagocytes in the immune system ............................................................1 1.1.1. Monocyte heterogeneity and differentiation..............................................................2 1.1.1.1. Monocyte heterogeneity...................................................................................2 1.1.1.2. Monocyte