Understanding the an English Agribusiness Lobby Group

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Applications of Machine Learning in Common Agricultural Policy at the Rural Payments Agency

Applications of Machine Learning in Common Agricultural Policy at the Rural Payments Agency Sanjay Rana Senior GIS Analyst GI Technical Team Reading 1 What are you gonna find out? • Knowing me and RPA (and knowing you - aha ?!) • How are we using Machine Learning at the RPA? – Current Activities – Random Forest for Making Crop Map of England – Work in Progress Activities – Deep Learning for Crop Map of England, Land Cover Segmentation, and locating Radio Frequency Interference • I will cover more on applications of Machine Learning for RPA operations, and less about technical solutions. 2 My resume so far… Geology GIS GeoComputation Academics Researcher & Radio DJ Consultant Civil Servant Lecturer Profession 3 Rural Payments Agency Rural Payments Agency (RPA) is the Defra agency responsible for the distribution of subsidies to farmers and landowners in England under all the EU's Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) schemes. 4 Area Based Payments/Subsidies Claim Claim Validation Visual Checks Machine Learning Control Helpline 5 A bit more info on Controls • To calculate correct CAP payments, the RPA Land Parcel Information System (LPIS) is constantly being updated with information from customers, OS MasterMap, Aerial Photographs and Satellite Images. • But, in addition as per EU regulations, claims from approximately 5% of customers must be controlled (i.e. checked) annually. Failure to make correct payments lead to large penalties for Member States. France had a disallowance of 1 billion euro for mismanaging CAP funds during 2009- 2013. • Controls/Checks are done either through regular Field Inspections (20%), or Remotely with Very High Resolution Satellite Images (80%) for specific areas* to ascertain farmer declaration of agricultural (e.g. -

Is Factory Farming Making Us Sick? IS FACTORY FARMING MAKING US SICK?

Is Factory Farming making us sick? IS FACTORY FARMING MAKING US SICK? A Guide to Animal Diseases and their Impact on Human Health 1 Photo by Engin Akyurt Contents Introduction 4 Avian Influenza (Bird Flu) 6 Bovine TB 8 BSE 10 Campylobacter 12 E. Coli (O157: H7) 14 Foot and Mouth Disease 16 Johne’s Disease 18 Meningitis 20 MRSA 22 Nipah 24 Q Fever 25 Salmonella 26 Swine Flu 28 Other Zoonotic Diseases 30 We can change 32 References 34 2 Is Factory Farming making us sick? 3 Photo by Ethan Kent Introduction The majority of farmed animals in the UK In recent years, animal farming has are reared intensively, inside crowded, filthy brought us outbreaks of BSE, bovine sheds which are the perfect environment TB, foot and mouth, bird flu, swine flu, for bacteria and viruses to flourish. Stressed campylobacter, salmonella and many by their surroundings and their inability more devastating diseases. No wonder to display natural behaviours, forced to the United Nations Food and Agriculture live in their own excrement alongside sick Organization has warned that global and dying animals, it is not surprising that industrial meat production poses a serious farmed animals are vulnerable to infection. threat to human health3. Their immunity is further weakened by the industry breeding from just a few CREATING ANTIBIOTIC high-yielding strains, which has led to genetic erosion. This makes it easier for RESISTANCE disease to sweep swiftly through a group Instead of protecting of animals, who are likely to share near- ourselves by changing identical genetics with little immunological how we treat animals resistance. -

A DNA Database in the NHS: Your Freedom up for Sale?

A DNA database in the NHS: Your freedom up for sale? May 2013 In April 2013, the Caldicott Committee, including Government Chief Scientist Sir Mark Walport, proposed new rules for data-sharing which would allow the Government to build a DNA database of the whole population of England in the NHS by stealth.1 The plan is to make NHS medical records and people’s genetic information available to commercial companies and to use public-private partnerships to build a system where all private information about every citizen is also accessible to the police, social workers, security services and Government. The Wellcome Trust, which was involved in the Human Genome Project and was led by Walport for ten years, has produced a plan which involves including a variant file, containing the whole genome of every person minus the reference genome, as an attachment to every medical record in the NHS in England.2 This data would be made available to ‘researchers’ (including commercial companies) for data-mining in the cloud and personalised risk assessments would be returned to individuals. The aim is to transform the NHS in line with proposals developed more than a decade ago by former GlaxoSmithKline Chairman Sir Richard Sykes. This is expected to massively expand the market for medicines, medical tests and other products, such as supplements and cholesterol-lowering margarines, by allowing products to be marketed to individuals based on personal risk assessments, created using statistical analysis of genetic data, medical records and other health information. The proposal to build a DNA database in the NHS was endorsed by the Human Genomics Strategy Group in 20123,4 and the Government (led by Prime Minister David Cameron) has quietly adopted this recommendation without telling members of the public. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Tuesday Volume 551 23 October 2012 No. 54 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday 23 October 2012 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2012 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 813 23 OCTOBER 2012 814 Mr Bone: The Conservative-led coalition Government House of Commons are increasing spending on the NHS, unlike what Labour would do. In my constituency, we will get an urgent care Tuesday 23 October 2012 centre in a few months as a result of Tory health reforms. People in Corby already have an urgent care centre as a result of Tory reforms. Does the Secretary of The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock State agree that, while Labour talks about the NHS, Conservatives deliver on the NHS? PRAYERS Mr Hunt: I absolutely agree with my hon. Friend. Indeed, last week we announced that waiting times are [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] at near-record lows. The number of hospital-acquired infections continues to go down and mixed-sex wards have been virtually eliminated. I am very pleased that BUSINESS BEFORE QUESTIONS my hon. Friend has an urgent care centre, and am sure that Mrs Bone will appreciate it even more than he does. NEW WRITs Ordered, Grahame M. Morris (Easington) (Lab): Does the That the Speaker do issue his Warrant to the Clerk of the Secretary of State recognise that the Office for National Crown to make out a new Writ for the electing of a Member to Statistics survey shows that the -

This Document Was Withdrawn on 6 November 2017

2017. November 6 on understanding withdrawn was water for wildlife document This Water resources and conservation: the eco-hydrological requirements of habitats and species Assessing We are the Environment Agency. It’s our job to look after your 2017. environment and make it a better place – for you, and for future generations. Your environment is the air you breathe, the water you drink and the ground you walk on. Working with business, Government and society as a whole, we are makingNovember your environment cleaner and healthier. 6 The Environment Agency. Out there, makingon your environment a better place. withdrawn was Published by: Environment Agency Rio House Waterside Drive, Aztec West Almondsbury, Bristol BS32 4UD Tel: 0870document 8506506 Email: [email protected] www.environment-agency.gov.uk This© Environment Agency All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced with prior permission of the Environment Agency. April 2007 Contents Brief summary 1. Introduction 2017. 2. Species and habitats 2.2.1 Coastal and halophytic habitats 2.2.2 Freshwater habitats 2.2.3 Temperate heath, scrub and grasslands 2.2.4 Raised bogs, fens, mires, alluvial forests and bog woodland November 2.3.1 Invertebrates 6 2.3.2 Fish and amphibians 2.3.3 Mammals on 2.3.4 Plants 2.3.5 Birds 3. Hydro-ecological domains and hydrological regimes 4 Assessment methods withdrawn 5. Case studies was 6. References 7. Glossary of abbreviations document This Environment Agency in partnership with Natural England and Countryside Council for Wales Understanding water for wildlife Contents Brief summary The Restoring Sustainable Abstraction (RSA) Programme was set up by the Environment Agency in 1999 to identify and catalogue2017. -

Healthy Ecosystems East Anglia a Landscape Enterprise Networks Opportunity Analysis

1 Healthy Ecosystems East Anglia A Landscape Enterprise Networks opportunity analysis Making Landscapes work for Business and Society Message LENs: Making landscapes 1 work for business and society This document sets out a new way in which businesses can work together to influence the assets in their local landscape that matter to their bottom line. It’s called the Landscape Enterprise Networks or ‘LENs’ Approach, and has been developed in partnership by BITC, Nestlé and 3Keel. Underpinning the LENs approach is a systematic understanding of businesses’ landscape dependencies. This is based on identifying: LANDSCAPE LANDSCAPE FUNCTIONS ASSETS The outcomes that beneficiaries The features and depend on from the landscape in characteristics LANDSCAPE order to be able to operate their in a landscape that underpin BENEFICIARIES businesses. These are a subset the delivery of those functions. Organisations that are of ecosystem services, in that These are like natural capital, dependent on the they are limited to functions in only no value is assigned to landscape. This is the which beneficiaries have them beyond the price ‘market’. sufficient commercial interest to beneficiaries are willing to pay make financial investments in to secure the landscape order to secure them. functions that the Natural Asset underpins. Funded by: It provides a mechanism It moves on from It pulls together coalitions It provides a mechanism Benefits 1 for businesses to start 2 theoretical natural capital 3 of common interest, 4 for ‘next generation’ intervening to landscape- valuations, to identify pooling resources to share diversification in the rural of LENs derived risk in their real-world value propositions the cost of land management economy - especially ‘backyards’; and transactions; interventions; relevant post-Brexit. -

The UK & Europe

The UK & Europe: The UK & Europe: Costs, Benefits, Options. Options. Benefits, Costs, The UK & Europe: Costs, Benefits, Options. The Regent’s Report 2013 The Report 2013 Regent’s Regent’s University London is one of the UK’s most respected independent universities and one of the most internationally diverse, with around 140 different student nationalities on campus. To order additional copies or download a digital version please visit www.regents.ac.uk/europereport Web www.regents.ac.uk/europereport Email [email protected] Price £25 1 The UK & Europe: Costs, Benefits, Options. The Regent’s Report 2013 © Regent’s University London. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form by any means without permission of the publishers. Published as part of the Institute of Contemporary European Studies at Regent’s University London. ISSN 2040-6059 (paper) ISSN 2040-6517 (online) First published in Great Britain in 2013 as part by Regent’s University London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4NS Printed by Belmont Press Typeset in Baskerville / Gill Sans Design by External Relations at Regent’s University London The information in this publication is distributed on an “as is” basis, without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation, neither the authors nor Regent’s University London shall have any direct liability to any person or organisation with respect to loss or damage caused or allegedly caused by use of the information provided. For more information please contact [email protected] Errata: Any corrections of amendments made after publication can be found at regents.ac.uk/europereport/errata 2 Vice Chancellor’s Foreword I hope that you find this Report informative and illuminating, and that it helps you to contribute to this important debate over the next few years. -

Understanding the Elements and Adoption of Environmental Best Practice in Horticulture

Understanding the elements and adoption of environmental best practice in horticulture Arthur Andersen Project Number: AH00018 AH00018 This report is published by Horticulture Australia Ltd to pass on information concerning horticultural research and development undertaken for Australian Horticulture. The research contained in this report was funded by Horticulture Australia Ltd with the financial support of all levy paying industries. All expressions of opinion are not to be regarded as expressing the opinion of Horticulture Australia Ltd or any authority of the Australian Government. The Company and the Australian Government accept no responsibility for any of the opinions or the accuracy of the information contained in this report and readers should rely upon their own enquiries in making decisions concerning their own interests. ISBN 0 7341 0459 6 Published and distributed by: Horticultural Australia Ltd Level 1 50 Carrington Street Sydney NSW 2000 Telephone: (02) 8295 2300 Fax: (02) 8295 2399 E-Mail: [email protected] © Copyright 2002 Horticulture Australia Contents Part 1: Executive Summary Part 2: Report Part 3: A guide to implementation Part 4: Appendices • Horticulture Australia ANDERSEN Introduction Understanding the elements and adoption The expected outcomes of the best practice of environmental best practice in study were to: horticulture' is a joint initiative of Horticulture • Gather information on management Australia limited (HAL) and the National practices which help minimise the Land and Water Resources -

DSV Spring Crop Plots

400 700 20 401 702 800 806 900 24 701 40 17 17 18 Lemken Harper Adams 807 20 Omex 501 Landquip Crop 15 15 1107 14 500 Househam Sprayers Ltd 802 804 University J Brock & Sons 901 1100 Alpler Agricultural Sprayers Billericay Farm 202 201QPH 203 9 10 10 Catering 2 100 Ltd 8 Altek-Lechler 8 8 8 Soil Association KRM Ltd Machinery LH Agro Services Griffith Elder 6 Shufflebottom 6 6 / Certification Microgenetics 10 108 54 36 36 36 280 600 425 216 135 360 300 375 330 64 56 225 150 300 160 120 260 102 18 9 6 6 6 20 25 25 27 15 20 25 22 8 7 15 15 20 15 26 13 18 12 40 10 12 120 12 12 15 10 40 1 101 204 2 205 402 3 403 502 4 503 704 5 6 809 902 7 903 1002 8 1003 1102 9 6 Creagh 6 Catering 3 17 Basak Concrete 10 10 10 10 Atlantis Tanks Products36 11 11 Barclays 12 12 Tractors Group Ltd 15 Strutt & Parker 15 15 15 16 Fruehauf 16 15 McConnel 15 905 15 McHale 15 Miedema 120 AHDB 100 143 6 Challow 6 20 Mercer 20 170 505 Chafer 144 Products 24 24 36 Machinery 103 207 Machinery 8 104 270 600 180 906 225 Isuzu Offroad Driving 6 Weirbags 6 Wilson 256 10 Extenda Line 10 907 60 60 6 10 10 402A 10 36 Wraight 706 54 206 9 9 1004 Course 7 Roythornes 7 504 150 12 12 200 105 80 Hugh Crane 106 Solicitors AHDB Pentair Terrington 77 15 15 45 45 10 (Cleaning 10 12 12 72 10 1005 507 Hypro EU 288 Machinery Tilhill 209 Spring Crop Plots - I Equipment) 96 12 12 6 6 Nuffield Forestry MHA MacIntyre Theatre 909 Farming 12 208 Hudson 100 100 42 72 811 908 10 15 15 Cleveland 14 14 10 CLA 10 600 508 Joskin SA 6 6 7 7 13 1006 72 708 Alliances 13 60 60 72 211 40 6 Sentry 6 Dual 36 NAAC Drainage Area 6 ODA UK 6 6 Pumps 6 42 107 150 36 Limited 10 108 Ltd 36 36 84 225 910 213 813 104 210 510 100 12 Fram Farmers 12 6 De Lacy 6 710 7 7 1007 Executive 509 911 Oil NRG 15 36 42 1008 Concept Karcher Farm 13 Lycetts 13 215 10 10 6 Miles 12 12 120 Drainage Machinery Centre JHS Team 912 Ltd 7 Laurence 7 1800 20 20 13 13 Ltd 36 2400 Gould 18 18 Sprayers 7 7 109 100 225 156 42 405 1010 72 1109 217 49 9 EPR Ely 9 511 110 216 MOBA 104 1009 6 Mobile 6 914 6 6 Landmark William Morfoot Eternit 7 72 R.A.B.I. -

Tom Jenkins Dr Kate Pressland

Plant. Grow. Innovate. O C T O B E R 9 T H - O C T O B E R 1 1 T H 2 0 2 0 V I R T U A L E V E N T London office +44 203 2878731 Europe Email address [email protected] South Asia Website www.thpoint0.io United Kingdom Contents I n t r o d u c t io n Introduction 2 From the British Agricultural Revolution of the 18th Programme 3 century to playing a fundamental part in the Green Revolution of the 1960s and 70s, the UK is no stranger Challenges 5 to agricultural innovation in evolving, growing and implementing revolutionary methods to increase productivity, drive efficiency and maximise yields. Challenge AgriTech Innovation 6 With the termination of the EU’s Common Agricultural Challenge Agri BioTech 7 Policy, new agricultural liinitiatives are driving and making it easier for the industry to embrace AgriTech, Challenge Smart Farming to enable innovation, and transform the agriculture, 8 horticulture and forestry sectors. Challenge Soil Productivity 9 There is now, and will continue to be, more opportunities for investment in the excellence of the UK Prizes 10 AgriTech sector to grow new businesses and export overseas. Judges 11 Keynote Speakers 13 Network/Clients 14 Contact Details 15 2 Programme Day 1 - Friday 9th October Day 3 - Sunday 11th October 19:00 - Official Launch 09:00 - Workshop - Pitch Perfect 19:30 - Final Team Formation 10:00 - Mentor Sessions 20:00 - Challenge Brief 12:00 - Final Demos 20:30 - Intro to Judges & Mentors 15:00 - Jury Deliberation 16:00 - Winner Announcement 16:30 - End of Hackathon Day 2 - Saturday 10th October -

2019-2020 PO No

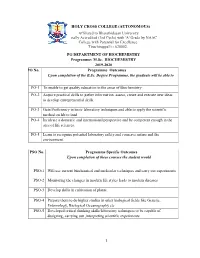

HOLY CROSS COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) Affiliated to Bharathidasan University Nationally Accredited (3rd Cycle) with 'A' Grade by NAAC College with Potential for Excellence. Tiruchirappalli - 620002. PG DEPARTMENT OF BIOCHEMISTRY Programme: M.Sc. BIOCHEMISTRY 2019-2020 PO No. Programme Outcomes Upon completion of the B.Sc. Degree Programme, the graduate will be able to PO-1 To enable to get quality education in the areas of Biochemistry PO-2 Acquire practical skills to gather information, assess, create and execute new ideas to develop entrepreneurial skills. PO-3 Gain Proficiency in basic laboratory techniques and able to apply the scientific method on lab to land PO-4 Inculcate a domestic and international perspective and be competent enough in the area of life sciences. PO-5 Learn to recognize potential laboratory safety and conserve nature and the environment. PSO No. Programme Specific Outcomes Upon completion of these courses the student would PSO-1 Will use current biochemical and molecular techniques and carry out experiments PSO-2 Monitoring the changes in modern life styles leads to modern diseases PSO-3 Develop skills in cultivation of plants. PSO-4 Prepare them to do higher studies in other biological fields like Genetic, Entomology, Biological Oceanography etc PSO-5 Developed critical thinking skills/laboratory techniques to be capable of designing, carrying out ,interpreting scientific experiments 1 HOLY CROSS COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) PG DEPARTMENT OF BIOCHEMISTRY (Students admitted from the year 2018 onwards) M.Sc. Biochemistry-Course -

Emerging Leaders 2019

Emerging Leaders 2019 Janelle Anderson Scottish Enterprise Rural Leadership Janelle is from a farming family based in Aberdeenshire. Their farming enterprise includes breeding cattle, a small flock of sheep and forestry. Having completed her Batchelor of Technology Degree in Agriculture in 2000, she currently works as Regional Events Manager for the Scottish Association of Young Farmers Clubs based at Thainstone Agricultural Centre and also manages the SAYFC Agri and Rural Affairs Group. Janelle is a director of the Royal Northern Agricultural Society, having been the society President in 2017. She is also past chairman of the North East Farm Management Association (2017/18) and currently secretary of the North East Aberdeen Angus Breeders Club. As well as having a long association with SAYFC as a member, from club to national level, she is also a trustee of John Fotheringham Memorial Trust and Willie Davidson 75th Fund which promotes health and safety amongst young farmers. Since being selected to represent Scotland at the Royal Agricultural Society of the Commonwealth Conference in Calgary in 2006, Janelle has kept a close link to the RASC, attending conferences in New Zealand and Zambia on behalf of the Royal Highland Agricultural Society of Scotland, who hosted the conference in Scotland in 2010 where Janelle was their Next Generation Leader. Janelle is honoured to be attending the Oxford Farming Conference on behalf of the Scottish Enterprise Rural Leaders and is looking forward to meeting the other delegates. James Beary 38-year-old James (Jim) is an upland tenant farmer from the Peak District, producing prime lambs on contract for Tesco.