Information Management for Collaboration in Construction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Change and Exchange Electronic Document Management in Building Design

Kurt Löwnertz Change and Exchange Electronic document management in building design Licentiate thesis Construction Management and Economics Royal Institute of Technology Stockholm, Sweden 1998 Construction Informatics Digital Library http://itc.scix.net/ paper fea8.content.05940 1 2 ABSTRACT Producing documents using computer supported methods has become common practice in the construction industry, but the management of documents is still to a large degree done with manual methods. Some pioneering users in design, construction and facility management respectively have applied electronic document management (EDM) within their organisations or for projects. How- ever, the introduction has hitherto been noticeably slow. This thesis discusses the benefits of the new document management techniques to the construction and facility management process, with focus on building de- sign, as well as the obstacles when implementing these techniques. The con- struction sector process has some particular properties, differing from other in- dustry sectors, in that a project organisation is formed anew for each project and involves a number of specialists with varying requirements for their company- internal production and management of documents. The main themes for EDM in building design are therefore how to manage the change of information and the exchange or sharing of information between the different organisations. The thesis contains a state-of-the-art description of document management in building design, including reviews of commercial applications, standards and current best practice. Basic techniques on a scale from file-hierarchy-based to product-model-based systems are classified and analysed from a building design perspective. Five cases of document management in practice have been studied. -

Plan De Estudio De Normas 2011

Presentación >> 3 Plan de estudio de Normas 2011 Como todos los años presentamos el Plan de estudio de NORMAS IRAM CON SIGLA MIXTA. Señala el caso de normas normas propuesto, en este caso, para el 2011, elaborado en base estudiadas bajo el régimen de convenios de cooperación técnica a las necesidades de normalización manifestadas por los concertados por IRAM con entidades de reconocida autoridad diversos sectores de la actividad económica y de los sectores en campos específicos. sociales, que abarca tanto el nivel nacional como el regional e internacional. NORMAS REGIONALES (COPANT / MERCOSUR) E La energía en sus distintas formas, sigue siendo una INTERNACIONALES (ISO / IEC). Incluye la nómina de prioridad dado su alto contenido estratégico que nos lleva a documentos desarrollados por estos organismos en los que ampliar a un mayor número de áreas y productos, el concepto IRAM actúa representando a nuestro país. de eficiencia energética. Se suma a este tema el concepto de la sostenibilidad de las actividades productivas que se ha transformado en una Cuando se indica: característica que recorre horizontalmente todas las áreas de (REV) significa que se trata de una norma en vigencia que está normalización. en revisión. La normalización internacional se hace eco de estas tendencias económicas e industriales y una de las tareas del (MOD) significa que se trata de un estudio de modificación a IRAM es difundirlas de modo de poder participar en su una norma en vigencia. evolución para ponerlas a disposición de nuestra sociedad. Para poder cumplir con este cometido, el IRAM está (ANT) significa que en el organismo de estudio se están presente en los foros regionales, hemisféricos e reuniendo antecedentes sobre ese tema, o bien que el primer internacionales, donde se estudian las normas que se documento preparado lleva ese nombre por estar incompleto relacionan con los intereses y oportunidades para el o porque se supone que será pasible de muchas intercambio y el desarrollo del país, tanto en lo referido a modificaciones. -

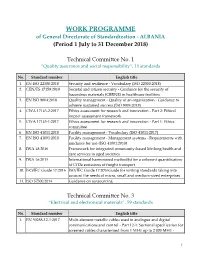

WORK PROGRAMME of General Directorate of Standardization - ALBANIA (Period 1 July to 31 December 2018)

WORK PROGRAMME of General Directorate of Standardization - ALBANIA (Period 1 July to 31 December 2018) Technical Committee No. 1 “Quality assurance and social responsibility”, 11 standards No. Standard number English title 1. EN ISO 22300:2018 Security and resilience - Vocabulary (ISO 22300:2018) 2. CEN/TS 17159:2018 Societal and citizen security - Guidance for the security of hazardous materials (CBRNE) in healthcare facilities 3. EN ISO 9004:2018 Quality management - Quality of an organization - Guidance to achieve sustained success (ISO 9004:2018) 4. CWA 17145-2:2017 Ethics assessment for research and innovation - Part 2: Ethical impact assessment framework 5. CWA 17145-1:2017 Ethics assessment for research and innovation - Part 1: Ethics committee 6. EN ISO 41011:2018 Facility management - Vocabulary (ISO 41011:2017) 7. EN ISO 41001:2018 Facility management - Management systems - Requirements with guidance for use (ISO 41001:2018) 8. IWA 18:2016 Framework for integrated community-based life-long health and care services in aged societies 9. IWA 16:2015 International harmonized method(s) for a coherent quantification of CO2e emissions of freight transport 10. ISO/IEC Guide 17:2016 ISO/IEC Guide 17:2016Guide for writing standards taking into account the needs of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises 11. ISO 37500:2014 Guidance on outsourcing Technical Committee No. 3 “Electrical and electronical materials”, 59 standards No. Standard number English title 1. EN 50288-12-1:2017 Multi-element metallic cables used in analogue and digital communications and control - Part 12-1: Sectional specification for screened cables characterised from 1 MHz up to 2 000 MHz - 1 Horizontal and building backbone cables 2. -

Manufacturing Engineering Services AST AEROSYSTEMS About AST

AST AEROSYSTEMS Manufacturing Engineering Services AST AEROSYSTEMS About AST AST is an innovative global product design and engineering solutions company with an emphasis on technical excellence and innovation. Our culture of customer centricity and a quality driven approach positions us as a preferred technology partner who provide inspired solutions to customer’s futuristic needs, by Design. Our deep domain expertise and engineering solution portfolio covers the complete product development lifecycle from concept evaluation to manufacturing support and certification for theAerospace, Energy, Transportation, Industrial Automation, Consumer Products and Heavy Engineering industries. Key Differentiator • Effective engineering service provider; Focused on Manufacturing domain • Perfect partner • Capability and domain expertise to address product lifecycle development • Capability in managing & executing engineering engagement, establishing Offshore Development Center’s for global Manufacturing Companies. Vision & Mission • To deliver Technology through innovation and integration of state-of-the-art technologies & to develop Manu facturing systems for global market. • To support Manufacturing Companies with Design, Develop services such as Manufacturing Equipment. • Deliver products & sub systems with best engineering solutions with Innovation to the global most complex challenges. • To be the best OEM & supplier of engineering services to global Manufacturing Companies. INTEGRATED DESIGN VALIDATION MANUFACTURING IN-SERVICE HEALTH USAGE -

Standards for Enabling Trade— Mapping and Gap Analysis Study

Standards for Enabling Trade— Mapping and Gap Analysis Study An IA-CEPA Early Outcomes Initiative November 2017 Standards For Enabling Trade—Mapping and Gap Analysis Study 2 An IA-CEPA Early Outcomes Initiative – November 2017 Contents ListofFigures..............................................................................................................3 Abbreviations...............................................................................................................4 Terms..........................................................................................................................6 Acknowledgements......................................................................................................8 ExplanatoryNotes........................................................................................................8 Foreword.....................................................................................................................9 Recommendations.....................................................................................................10 ExecutiveSummary....................................................................................................11 Introduction................................................................................................................13 ProjectPurpose.........................................................................................................13 Objectives..................................................................................................................13 -

Veiklų Įgyvendinimo Specifikacija

Projekto Nr. 10.1.1-ESFA-V-912-01-0029 „Priemonių, skirtų viešojo sektoriaus statinių gyvavimo ciklo procesų efektyvumui didinti, taikant statinio informacinį modeliavimą, sukūrimas“ (BIM-LT projektas) VEIKLŲ ĮGYVENDINIMO SPECIFIKACIJA Parengė: V. Popov D. Pupeikis T. Vilutienė T. Grigorjeva J. Stankevičienė R. Butleris L. Čeponienė T. Danikauskas M. Jurgelaitis K. Kapočius T. Skersys A. A. Navickas J. Černeckienė Versija v_0.8 2020 m. Projektas Nr. 10.1.1-ESFA-V-912-01-0029 „Priemonių, skirtų viešojo sektoriaus statinių gyvavimo ciklo Derinimo versija: 0.8 procesų efektyvumui didinti, taikant statinio informacinį modeliavimą, sukūrimas“ – 1.1. Specifikavimo veikla BIM-LT Projekto veiklų įgyvendinimo specifikacija _v0.8 Data: 2020-03-30 Dokumento istorija Data Versija Aprašymas Autorius 2020-02-07 0.1 Pateikta PVKG V. Popov derinti D. Pupeikis T. Vilutienė T. Grigorjeva J. Stankevičienė R. Butleris L. Čeponienė T. Danikauskas M. Jurgelaitis K. Kapočius T. Skersys 2020-02-14 0.2 PVKG pastabos A.Balsytė V.Žėkas D.Šimkus I. E. Germanaitė M. Javorovic R. Kvedaravičius K. Maželis 2020-02-21 0.3 Pateikta PVKG V. Popov derinti D. Pupeikis T. Vilutienė T. Grigorjeva J. Stankevičienė R. Butleris L. Čeponienė T. Danikauskas M. Jurgelaitis K. Kapočius T. Skersys 2020-02-28 0.4 PVKG pastabos A.Balsytė V.Žėkas D.Šimkus I. E. Germanaitė M. Javorovic R. Kvedaravičius K. Maželis T. Boldorevas 2020-03-11 0.5 Pateikta PVKG V. Popov derinti D. Pupeikis T. Vilutienė T. Grigorjeva J. Stankevičienė R. Butleris L. Čeponienė Projektas Nr. 10.1.1-ESFA-V-912-01-0029 „Priemonių, skirtų viešojo sektoriaus statinių gyvavimo ciklo Derinimo versija: 0.8 procesų efektyvumui didinti, taikant statinio informacinį modeliavimą, sukūrimas“ – 1.1. -

HZN Oglasnik Za Normativne Dokumente 2

Hrvatski zavod za norme Oglasnik za normativne dokumente 2/2018 veljača, 2018. Oglasnik za normativne dokumente Hrvatskog zavoda za norme sadrži popise hrvatskih norma, nacrta hrvatskih norma, prijedloga za prihvaćanje stranih norma u izvorniku, povučene hrvatske norme, povučene nacrte hrvatskih norma te ispravke, rezultate europske i međunarodne normizacije razvrstane po predmetnom ustroju i obavijesti HZN-a. Tko u popisima normativnih dokumenata koji su objavljeni u ovom Oglasniku otkrije koju grešku, koja može voditi do krive primjene, moli se da o tome neodložno obavijesti Hrvatski zavod za norme, kako bi se mogli otkloniti uočeni propusti. Izdavač: Sadržaj: 1 Rezultati hrvatske normizacije .................................................................................................. A3 1.1 Hrvatske norme ....................................................................................................................................... A3 1. Nacrti hrvatskih norma ............................................................................................................................ A9 1.3 Prijedlozi za prihvaćanje stranih norma u izvorniku ................................................................................ A9 1.4 Povučene hrvatske norme ...................................................................................................................... A14 1.5 Povučeni nacrti hrvatskih norma ............................................................................................................. 1.6 Ispravci -

ISO 128-1:2003 Technical Drawings—General Principles of Presentation—Part 1

ISO 128-1:2003 Technical drawings—General principles of presentation—Part 1: Introduction and index • ISO 128-20:1996 Technical drawings—General principles of presentation—Part 20: Basic conventions for lines • ISO 128-21:1997 Technical drawings—General principles of presentation—Part 21: Preparation of lines by CAD systems • ISO 128-22:1999 Technical drawings—General principles of presentation—Part 22: Basic conventions and applications for leader lines and reference lines • ISO 128-23:1999 Technical drawings—General principles of presentation—Part 23: Lines on construction drawings • ISO 128-24:2014 Technical drawings—General principles of presentation—Part 24: Lines on mechanical engineering drawings • ISO 128-30:2001 Technical drawings—General principles of presentation—Part 30: Basic conventions for views • ISO 128-34:2001 Technical drawings—General principles of presentation—Part 34: Views on mechanical engineering drawings • ISO 128-40:2001 Technical drawings—General principles of presentation—Part 40: Basic conventions for cuts and sections • ISO 128-44:2001 Technical drawings—General principles of presentation—Part 44: Sections on mechanical engineering drawings • ISO 128-50:2001 Technical drawings—General principles of presentation—Part 50: Basic conventions for representing areas on cuts and sections ISO 129 Technical drawings—Indication of dimensions and tolerances ISO 216 paper sizes, e.g. the A4 paper size ISO 406:1987 Technical drawings—Tolerancing of linear and angular dimensions ISO 1660:1987 Technical drawings—Dimensioning -

Computer Aided Drafting (CAD) Standards Facilities Planning and Construction OCTOBER 2020

Computer Aided Drafting (CAD) Standards Facilities Planning and Construction OCTOBER 2020 University of Nebraska CAD Standards Table of Contents 1 Introduction ..............................................................................................................................................3 1.1 The Need for (CAD) Standards ........................................................................................................3 1.2 Building Information Modeling (BIM) ................................................................................................3 1.3 Standard of Production ....................................................................................................................3 2 CAD Drawing Setup Process ..................................................................................................................4 2.1 CAD Drawing File Format ................................................................................................................4 2.2 Sheet Numbering and File Identification ..........................................................................................4 2.2.1 Sheet Numbering .....................................................................................................................4 2.2.2 File Identification ......................................................................................................................4 2.2.3 Alternate File Identification .......................................................................................................4 -

CAD Standardisation in the Construction Industry - a Process View, Automation in Construction, Vol 19, No

PERSONAL VERSION This is a so-called personal version (author's manuscript as accepted for publishing after the review process but prior to final layout and copyediting) of the article Björk, Bo-Christer and Laakso, Mikael. 2010, CAD standardisation in the construction industry - a process view, Automation in Construction, Vol 19, No. 4, pp. 398-406 Readers are kindly asked to use the official publication in references CAD standardisation in the construction industry – a process view Bo-Christer Björk & Mikael Laakso Hanken School of Economics, Arkadiankatu 22, PO Box 479, 00101 Helsinki, Finland Abstract There has been a demand for uniform CAD standards in the construction industry ever since the large-scale introduction of computer aided design systems in the late 1980s. While some standards have been widely adopted without much formal effort, other standards have failed to gain support even though considerable resources have been allocated for the purpose. Establishing a standard concerning building information modeling has been one particularly active area of industry development and scientific interest within recent years. In this paper, four different standards are discussed as cases: the IGES and DXF/DWG standards for representing the graphics in 2D drawings, the ISO 13567 standard for the structuring of building information on layers, and the IFC standard for building product models. Based on a literature study combined with two qualitative interview studies with domain experts, a process model is proposed to describe and interpret the contrasting histories of past CAD standardisation processes. Keywords: standardisation process, computer aided design, building information modelling, industry foundation classes 1. Introduction enable the seamless communication Standards provide an essential ingredient between computers and software to the ubiquitous use of IT in everyday life applications in a world-wide network. -

List of ISO Standards - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

List of ISO standards - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Log in / create account Wikipedia: Making Life Easier. [Collapse] Article Discussion Edit this page History $3,376,364 Our Goal: $6 million Donate Now » List of ISO standards Navigation From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia ● Main page ● Contents This is a list of ISO standards that are discussed in Wikipedia articles. For a list of all the more than 16,000 ISO standards (as of ● Featured content 2007), see the ISO Catalogue. ● Current events About 300 of the standards produced by ISO and IEC's Joint Technical Committee 1 (JTC1) have been made freely/publicly ● Random article [ ] available. 1 Search Contents [hide] ● 1 ISO 1–ISO 999 Interaction ● 2 ISO 1000–ISO 9999 ● About Wikipedia ● 3 ISO 10000–ISO ● Community portal 19999 ● Recent changes ● 4 ISO 20000–ISO ● Contact Wikipedia 29999 ● Donate to Wikipedia ● 5 ISO 30000–ISO ● Help 39999 Toolbox ● 6 Other standards ● What links here ● 7 See also ● Related changes ● 8 References ● Upload file ● 9 External links http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ISO_standards (1 of 20)05/12/2008 10:36:09 • List of ISO standards - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia ● Special pages ● Printable version ISO 1–ISO 999 [edit] ● Permanent link ● ISO 1 Standard reference temperature for geometrical product specification and verification ● Cite this page ● ISO 3 Preferred numbers Languages ● ISO 4 Rules for the abbreviation of title words and titles of publications ● Deutsch ● ISO 7 Pipe threads where pressure-tight joints are made on the threads ● Español ● ISO 9 Information and documentation — Transliteration of Cyrillic characters into Roman characters — Slavic and non-Slavic ● ••••• languages ● Français ● ● •••••• ISO 16:1975 Acoustics — Standard tuning frequency (Standard musical pitch) ● Íslenska ● ISO 31 Quantities and units ● Italiano ● ISO 68-1 Basic profile of metric screw threads ● Nederlands ● ISO 216 paper sizes, e.g. -

Nieuwe Normen NEN

NEN Nieuwe normen NEN Overzicht van nieuwe publicaties van productdocumentatie; Organisatie en Gevulkaniseerde of thermoplastische het Nederlands Normalisatie- benaming van lagen bij CAD; Deel 1: rubber; Bepaling van de spannings- Instituut, inclusief de Europese nor- Overzicht en principe. (en). Prijs vermindering onder druk bij omge- men, in de periode 8 februari 2001 f 63,89. vings- en verhoogde temperaturen. tot 7 maart 2001. De prijzen voor de NEN-ISO 13567-2:2001 – Technische (en). Prijs f 21,86. normen afkomstig van ETSI in de productdocumentatie; Organisatie en NEN-EN-ISO 3497:2001 – Metallieke rubriek ‘Telecommunicatie’ zijn op benaming van lagen bij CAD; Deel 2: deklagen; Meting van de dikte van de aanvraag beschikbaar. De normbla- Concepten, opmaak en codes deklaag; Spectrometrische methode den kunnen worden besteld bij NEN- gebruikt in gebouwdocumentatie. met röntgenstraling. (en). Prijs Klantenservice, tel. 015-2690391. (en). Prijs f 94,14. f 134,49. Tevens kunnen de genoemde normen NPR-ISO/TR 13567-3:2001 – NEN-EN-ISO 3543:2001 – Metallieke via Internet besteld worden Technische productdocumentatie; en niet-metallieke deklagen; Meting (www.nen.nl). Met vragen kunt u Organisatie en benaming van lagen van de dikte; Methode met beta- terecht bij NEN-Klantenservice, tel. bij CAD; Deel 3: Toepassing van ISO terugstraling. (en). Prijs f 114,32. 015-2690391. Correspondentie-adres: 13567-1 en ISO 13567-2. (en). Prijs NEN-ISO 4097:2001 – Ethyleen-pro- postbus 5059, 2600 GB Delft. f 104,23. pyleen-dieen (EPDM) rubber; NEN 3509:1998/C1:2001 – Trappen Beoordelingsprocedure. (en). Prijs Bouw in woningen en woongebouwen; f 104,23. Termen, definities en afmetingen.