Sample Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'unfp Au Cœur De La Crise

eptembre 2020 eptembre S N°22/ Michel Hidalgo SA VIE EST UN ROMAN Le magazine de l’Union nationale des footballeurs professionnels - professionnels footballeurs magazine de l’Union nationale des Le Jonas Bär-Hoffmann « Le football joue actuellement avec la santé des joueurs ! » L’UNFP au cœur de la crise Sommaire Profession Footballeur Numéro 22 – Septembre 2020 ÉDITO p.4 ENTRE NOUS Crise sanitaire p.6 06 L’UNFP au cœur de la crise 16 Hommage p.16 Michel Hidalgo Sa vie est un roman In memoriam p.20 De grands serviteurs du football On en parle p.22 Féminines p.23 Élise Bonet 20 AUTOUR DE NOUS 23 Positive Football p.24 S’engager pour la société encore et toujours Interview p.28 Jonas Bär-Hoffmann « Le football joue actuellement avec la santé des joueurs ! » 24 28 Édito TEXTE Philippe Piat En France, comme ailleurs. Mais si beaucoup chez nous ont repris à leur compte l’impérieuse nécessité d’un changement Coprésident de l’UNFP – Président de la FIFPRO radical, combien sont allés pour le moment au-delà des belles intentions de principe, combien ont, comme l’UNFP, prôné l’union, appelé à un dialogue constructif, posé sur Haut les filles, la table des propositions réalistes pour un football plus juste, plus solidaire, aussi ? Très actif tout au long de ce drôle de printemps, plus que haut les filles… jamais à l’écoute des footballeurs.euses qu’il représente, notre syndicat s’est d’abord attaché à protéger, coûte que coûte, la santé des acteurs. Grâce à l’Olympique de Marseille, vainqueur en 1993, la France compte Non seulement parce qu’ils nous le demandaient, décidés aujourd’hui huit Ligues des champions ! à se protéger pour mieux préserver leur famille, mais aussi Qu’on ne s’y trompe pas ! Cette introduction n’a pas d’autre raison d’être parce que rien ne saurait justifier à nos yeux que l’on puisse que de glorifier le parcours coruscant des footballeuses de l’Olympique mettre en danger la vie d’une footballeuse ou d’un footballeur. -

Disparition De Jean-Pierre Kress

02/10/2021 13:59 https://racingstub.com Cette page peut être consultée en ligne à l'adresse https://racingstub.com/articles/18645-disparition-de-jean-pierre-kress Disparition de Jean-Pierre Kress 0.0 / 5 (0 note) 05/05/2021 05:00 Souvenir/anecdote Lu 1.713 fois Par kitl 1 comm. Cet ancien gardien de but international aura occupé plusieurs fonctions au sein du Racing, avec pour fil rouge la formation. Sa carrière professionnelle aura été brève, mais couronnée d’une sélection en Equipe de France quelques mois à peine après ses débuts. Jean-Pierre Kress a par la suite occupé la fonction de président du centre de formation au moment où le fonctionnement du RC Strasbourg pouvait s’apparenter à celui d’un gros club amateur, avec sa section professionnelle indépendante et de multiples équipes de jeunes, sans parler des sections de l’omnisports. La vingtaine arrivée, Jean-Pierre Kress intègre les « Cigogneaux », cet embryon de centre de formation mis sur pied au début des années 1950. Le joueur Alexandre Vanags est chargé de préparer la relève en rassemblant les meilleurs éléments du terroir local. Kress se distingue rapidement au point de garder la cage du Racing en Coupe de France contre l’ASS (6-0) en décembre 1952. A ses côtés, deux autres gamins, Alex Oertel et un arrière droit appelé à un bel avenir, Jean Wendling. En début de saison suivante, alors que Lucien Schaeffer a rejoint Valenciennes, le RCS se met en quête d’un portier titulaire. Le Monégasque Robert Germain est approché, le Sochalien Pierre Lorius est mis à l’essai avant que Josef ‘’Pepi’’ Humpal ne jette son dévolu sur le jeune Kress. -

Super Foot 83

. i y I V/vS *:7. I: .• " .. -i I ' î . I' 1 I ' I:: ï " : , I ; i: «r. ^ ^ ^ ^ " **wmmr '' m 3 I . :# f:. ^ , ;. |: . % À MM*?' ^ 1f ;? # fc: -':^âj ' -^'gi ... ;: '% ^ &• -, ^ "-. ^1k ^ ^ j ^ ^ ^ |fe' %, :#- -:^f- S^5"' '~ï' Vit. Ngp<.,. ^ : "™-.^ Il Monique PIVOT Jean-Philippe RÉTHACKER HACHETTE ' 1983 Hachette AutantA qu'un panorama de la saison écoulée, Super Foot 83 vous offre des perspectives sur celle à venir et vous propose une fiche détaillée des quatre-vingt-seize meilleurs joueurs français et étrangers: à côté des caractéristiques essentielles sur chacun d'eux, un emplacement a été réservé afin de permettre aux vrais «mordus» de faire signer Giresse, Rocheteau, Platini et les autres. Ces fiches, détachables, constituent une grande première dans la littérature sportive. Elles ne constituent pas, pourtant, le seul objet de ce livre qui se veut, en même temps qu'un bilan, une réflexion sur le plus populaire des sports. L'aventure des Bleus lors du Mundial a encore accru l'audience et le prestige du football en France, c'est pourquoi vous trouverez ici, non seulement les photos des phases de jeu les plus spectaculaires et les plus représentatives, mais aussi des articles sur les clubs, les événements et les hommes les plus marquants de l'année. Les stars du football et ceux qui sont en train de le devenir ont donc rendez-vous dans Super Foot 83 pour, nous l'espérons, votre plus grand plaisir. Monique Pivot Jean-Philippe Réthacker AUX 4 POINTS CARDINAUX Prenons notre boussole. Pour une fois, elle indique l'Ouest et non le Nord. Cette bous- sole-là, en effet, a été formée aux affaires du football, et elle n'ignore pas que la Bretagne a été la région la mieux repré- sentée lors du championnat 82-83. -

Goalden Times: December, 2011 Edition

GOALDEN TIMES 0 December, 2011 1 GOALDEN TIMES Declaration: The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the authors of the respective articles and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Goalden Times. All the logos and symbols of teams are the respective trademarks of the teams and national federations. The images are the sole property of the owners. However none of the materials published here can fully or partially be used without prior written permission from Goalden Times. If anyone finds any of the contents objectionable for any reasons, do reach out to us at [email protected]. We shall take necessary actions accordingly. Cover Illustration: Neena Majumdar & Srinwantu Dey Logo Design: Avik Kumar Maitra Design and Concepts: Tulika Das Website: www.goaldentimes.org Email: [email protected] Facebook: Goalden Times http://www.facebook.com/pages/GOALden-Times/160385524032953 Twitter: http://twitter.com/#!/goaldentimes December, 2011 GOALDEN TIMES 2 GT December 2011 Team P.S. Special Thanks to Tulika Das for her contribution in the Compile&Publish Process December, 2011 3 GOALDEN TIMES | Edition V | First Whistle …………5 Goalden Times is all set for the New Year Euro 2012 Group Preview …………7 Building up towards EURO 2012 in Poland-Ukraine, we review one group at a time, starting with Group A. Is the easiest group really 'easy'? ‘Glory’ – We, the Hunters …………18 The internet-based football forums treat them as pests. But does a glory hunter really have anything to be ashamed of? Hengul -

Le Stade De Reims Et La Coupe De France 2Ème Partie.Xlsx

LE STADE DE REIMS ET LA COUPE DE FRANCE DE FOOTBALL PARCOURS DES ROUGE ET BLANC DEPUIS LES 32èmes DE FINALE RETROSPECTIVE - DEUXIEME PARTIE SAISON 1959/1960 à 1969/1970 SAISON NIVEAU de l'EPREUVE DATE LIEU du MATCH ADVERSAIRE RESULTAT BUTEURS DU STADE DE REIMS 32ème 24/01/1960 Mulhouse C.S. Blénod Reims 4-0 Raymond Kopa, Lucien Muller 2 et Robert Bérard Le Stade de Reims Gardien : Dominique Colonna - Défenseurs : Bruno Rodzik, Robert Jonquet, Raoul Giraudo - Demis : Michel Leblond (Entr : Albert Batteux) Robert Siatka - Avants : Robert Bérard, Lucien Muller, Raymond Kopa, Roger Piantoni, Jean Vincent 16ème 14/02/1960 Bordeaux F.C. Rouen Reims 3-2 Just Fontaine, Jean Vincent (2) Le Stade de Reims Gardien : Dominique Colonna - Défenseurs : Jean Wendling, Robert Siatka, Bruno Rodzik - Demis : Michel Leblond (Entr : Albert Batteux) Raymond Baratto - Avants : Just Fontaine, Lucien Muller, Raymond Kopa, Roger Piantoni, Jean Vincent 1959-1960 1/8ème 06/03/1960 Colombes Nîmes Olympique Reims 3-2 Lucien Muller, Jean Vincent, Just Fontaine Le Stade de Reims Gardien : Dominique Colonna - Défenseurs : Jean Wendling, Robert Siatka, Bruno Rodzik - Demis : Michel Leblond (Entr : Albert Batteux) Raymond Baratto - Avants : Just Fontaine, Lucien Muller, Raymond Kopa, Roger Piantoni, Jean Vincent 1/4 03/04/1960 Marseille Sète Reims 1-0 Jean Vincent - 96ème mn - (après prolong) Le Stade de Reims Gardien : Dominique Colonna - Défenseurs : Jean Wendling, Robert Jonquet, Bruno Rodzik - Demis : Michel Leblond (Entr : Albert Batteux) Robert Siatka - Avants : Robert Bérard, Lucien Muller, Raymond Kopa, Roger Piantoni, Jean Vincent SAISON NIVEAU de l'EPREUVE DATE LIEU du MATCH ADVERSAIRE RESULTAT BUTEURS DU STADE DE REIMS 1/2 24/04/1960 Colombes A.S. -

World Cup France 98: Metaphors

The final definitive version of this article has been published as: 'World Cup France 98: Metaphors, meanings, and values', International Review for the Sociology of Sport , 35 (3) By SAGE publications on SAGE Journals online http://online.sagepub.com World Cup France ‘98: Metaphors, Meanings and Values Hugh Dauncey and Geoff Hare (University of Newcastle upon Tyne) The 1998 World Cup Finals focused the attention of the world on France. The cumulative television audience for the 64 matches was nearly 40 billion - the biggest ever audience for a single event. French political and economic decision makers were very aware, as will be seen, that for a month the eyes of the world were on France. On the night of July 12th, whether in Paris and other cities or in smaller communities all over France, there was an outpouring of joy and sentiment that was unprecedented - at least, most people agreed, since the Liberation of 1944. Huge numbers of people watched the final, whether at home on TV or in bars or in front of one of the giant screens erected in many large towns, and then poured onto the streets in spontaneous and good-humoured celebration. In Paris, hundreds of thousands gathered again on the Champs Elysées the next day to see the Cup paraded in an open-topped bus. For all, the victory was an unforgettable experience. An element that was commented on by many was the appropriation by the crowds of the red, white and blue national colours: manufacturers of the French national flag had never known such demand since the death of General de Gaulle. -

Karriere-Tore (Verein, Nationalteam)

KARRIERE-TORE (Verein + Nationalteam) Stand: 15.07.2021 Gesamt 1. Liga Div. Ligen Cup / Supercup Int. Cup Länderspiele Torschütze geb.Land Liga Karriere Sp. Tore Qu. Sp. Tore Qu. Sp. Tore Qu. Sp. Tore Qu. Sp. Tore Qu. Sp. Tore Qu. 1 Pelé Edson Arantes 1940 BRA1 BRA,USA 1957-1977 854 784 0,92 237 137 0,58 412 470 1,14 96 76 0,79 18 24 1,33 91 77 0,85 2 Cristiano Ronaldo 1985 POR1 POR,ENG,ESP,ITA 2002-2021 1073 783 0,73 610 479 0,79 - - - 92 51 0,55 192 144 0,75 179 109 0,61 3 Josef Bican 1913 AUT1/CSR1 AUT,CSR 1931-1955 492 756 1,54 216 260 1,20 165 313 1,90 61 130 2,13 15 15 1,00 35 38 1,09 4 Lionel Messi 1987 ARG1 ESP 2004-2021 929 748 0,81 520 474 0,91 - - - 100 70 0,70 158 128 0,81 151 76 0,50 5 Romário de Souza 1966 BRA2 BRA,NED,ESP,QAT,AUS 1985-2007 956 736 0,77 424 293 0,69 278 246 0,88 113 92 0,81 71 50 0,70 70 55 0,79 6 Ferenc Puskás 1927 HUN1/ESP1 HUN,ESP 1943-1966 717 706 0,98 529 514 0,97 - - - 52 66 1,27 47 42 0,89 89 84 0,94 7 Gerd Müller 1945 GER1 GER,USA 1965-1981 745 672 0,90 498 403 0,81 26 33 1,27 80 98 1,23 79 70 0,89 62 68 1,10 8 Zlatan Ibrahimovic 1981 SWE1 SWE,NED,ITA,ESP,FRA,ENG,USA 1999-2021 954 565 0,59 586 385 0,66 26 12 0,46 80 49 0,61 144 57 0,40 118 62 0,53 9 Eusébio Ferreira 1942 POR2 MOZ,POR,USA,MEX 1960-1977 593 555 0,94 361 339 0,94 32 39 1,22 61 79 1,30 75 57 0,76 64 41 0,64 10 Jimmy McGrory 1904 SCO1 SCO 1922-1938 547 550 1,01 408 408 1,00 - - - 126 130 1,03 6 6 1,00 7 6 0,86 11 Fernando Peyroteo 1918 POR3 POR 1937-1949 351 549 1,56 197 329 1,67 91 133 1,46 43 73 1,70 - - - 20 14 0,70 12 Uwe Seeler 1936 -

Football in Europe.Pdf

University of Pristina, Faculty of FIEP Europe – History of Sport and Physical Education in Physical Education and Sport Leposaviæ Section Book: FOOTBALL IN EUROPE Editors: Petar D. Pavlovic (Republic of Srpska) Nenad Zivanovic (Serbia) Branislav Antala (Slovakia) Kristina M. Pantelic Babic, (Republic of Srpska) Publishers: University of Pristina, Faculty of Sport and Physical Education in Leposavic FIEP Europe - History of Physical Education and Sport Section For publishers: Veroljub Stankovic Nenad Zivanovic 2 Reviewers: Branislav Antala (Slovakia) Nenad Zivanovic (Serbia) Sladjana Mijatovic (Serbia) Nicolae Ochiana (Romania) Veroljub Stankovic (Serbia) Violeta Siljak (Serbia) Prepress: Kristina M. Pantelic Babic Book-jacket: Anton Lednicky Circulation: Printed by: ISBN NOTE: No part of this publication may be reproduced without the prior permission of the authors. 3 Authors: Balint Gheorghe (Romania) Dejan Milenkovic (Serbia) Elizaveta Alekseevna Bogacheva (Russia) Emeljanovas Arūnas (Lithuania) Fedor Ivanovich Sobyanin (Russia) Ferman Konukman (Turkey) Giyasettin Demirhan (Turkey) Igor Alekseevich Ruckoy (Russia) Javier Arranz Albó (Spain) Kristina M. Pantelic Babic (Republic of Srpska) Majauskienė Daiva (Lithuania) Petar D. Pavlovic (Republic of Srpska) Sergii Ivashchenko (Ukraine) Zamfir George Marius (Romania) 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ............................................................................................. 6 FROM THE RISE OF FOOTBALL IN LITHUANIA TO THE PARTICIPATION OF THE LITHUANIAN FOOTBALL SELECTION -

When Friday Comes #2 (2014 – 120 Jahre VIENNA)

Howa 1930 Vienna Archiv Howa 1926 Vienna Archiv Liebe Vienna-Family! „Und ob als Sieger, ob besiegt, es ist Jahre 1. Liga nicht fehlen und wir wagen sogar ganz gleich, wer unterliegt, das Schicksal ist einen Ausblick in die Zukunft. heut‘ nicht imstand, zu lockern unser Band!“ Möglich gemacht wurde dieses Projekt, – so heißt es schon im Vienna-Lied aus den in dem „Fans“ für „Fans“ schreiben, durch den Anfängen. Die Vienna und ihre Fans sind etwas blau-gelben Fandachverband „First Vienna ganz Besonderes und so feiern wir gemeinsam Football Club 1894 Supporters“. Dieser hat sich am 22. August 2014 unseren 120. Geburtstag. im Februar 2014 gegründet und verfügt schon Seitdem die Gärtner der Rothschilds das über eine dreistellige Anzahl an Mitgliedern. „englische Spiel“ nach Wien verpflanzten ist viel Die Vienna Supporters haben es sich passiert. Die Döblinger leisteten Pionierarbeit zu ihrer Aufgabe gemacht, den verschiedenen auf allen Ebenen des österreichischen unterschiedlichen Fananliegen im Verein eine Fußballsports, feierten große Erfolge und Stimme zu verleihen und die Zusammenarbeit durchlebten Höhen und Tiefen. Ungebrochen und Kommunikation zu stärken. So soll diese stehen wir Fans zu unserer geliebten Vienna „Fanfestschrift“ ein Startschuss für weitere und feiern unsere Blau-Gelben in guten wie in Projekte sein, wie etwa die Aufarbeitung und schlechten Zeiten auf „unserer“ Hohen Warte, Sicherung des Vienna-Archivs durch die mit der wir untrennbar verwurzelt sind. Fans. Im Gegensatz zur Generalversammlung Aus unserer Mitte hat sich ein kleiner Kreis Ende Mai verliefen die Gespräche mit dem von Vienna-SympathisantInnen zusammen- „Vienna“-Präsidium in den letzten Wochen getan, um dieses Fanzine anlässlich des runden überaus produktiv. -

Diplomarbeit

Diplomarbeit Titel der Diplomarbeit „Der Einfluss von sportlichen Großereignissen auf das Österreichbewusstsein in der Nachkriegszeit zwischen 1945 und 1956, anhand der Fußballweltmeisterschaft 1954 und den Olympischen Spielen 1956“ Verfasser Mag. Farkas Benedikt angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 190 482 313 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Lehramtsstudium UF Bewegung und Sport UF Geschichte, Sozialkunde, Polit. Bildg Betreuer: Univ.-Doz. Dr. Bertrand Perz Ich möchte mich an dieser Stelle bei allen Menschen, insbesondere bei meiner Familie, bedanken, die mich während meines Studiums unterstützt haben. Ich möchte auch meinem Betreuer Univ.-Doz. Dr. Bertrand Perz für die Zusammenarbeit und gute Beratung Dank sagen. 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung ........................................................................................................................................... 6 2. Geschichtlicher Hintergrund ........................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Nachkriegssituation ................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Staatsvertrag............................................................................................................................... 9 2.3 Ziele der Alliierten in Österreich ............................................................................................. 12 2.4 Die österreichischen -

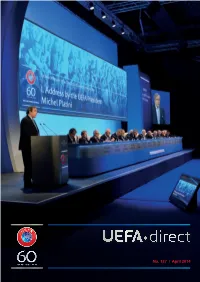

UEFA"Direct #137 (04.2014)

No. 137 | April 2014 IN THIS ISSUE Official publication of the UEFA CONGRESS IN ASTANA 4 Union of European Football Associations UEFA held its 38th Ordinary Congress in Astana, Kazakhstan, Images where the national association delegates supported various important measures for the future of football. Getty Chief editor: Emmanuel Deconche Produced by: Atema Communication SA, CH-1196 Gland PULLING OUT ALL THE STOPS IN LISBON Printing: 12 Artgraphic Cavin SA, The Portuguese capital is hosting lots of UEFA events Images PA / CH-1422 Grandson in May in connection with the men’s and women’s Champions Editorial deadline: League finals. UEFA 7 April 2014 The views expressed in signed articles are not necessarily the official views of UEFA. EUROPEAN U17 CHAMPIONSHIP The reproduction of articles FINALS IN MALTA 15 published in UEFA·direct is authorised, provided the The eight teams still in the running for the title of European source is indicated. Under-17 champions are heading to Malta for the final tournament Images from 9 to 21 May. Getty EVENTS FOR BLIND AND PARTIALLY SIGHTED ATHLETES 16 As part of its social responsibility programme, UEFA has teamed up with the International Blind Sports Federation to help blind and partially sighted people to play football on a regular basis. Sportsfile Cover: NEWS FROM MEMBER ASSOCIATIONS 19 The 2014 UEFA Congress took place on 27 March in the Kazakh capital, Astana. Photo: Getty Images WITH THIS ISSUE Issue 22 of UEFA•medicine matters presents the latest theories on recovery in professional football, papers on heat stress and the relative age effect in Spanish football, and a report on UEFA’s Elite Club Injury Study. -

Grands Stades Et Arénas : Pour Un Financement Public Les Yeux Ouverts »

N° 86 SÉNAT SESSION ORDINAIRE DE 2013-2014 Enregistré à la Présidence du Sénat le 17 octobre 2013 RAPPORT D´INFORMATION FAIT au nom de la commission de la culture, de l'éducation et de la communication (1) et de la commission des finances (2) sur le financement public des grandes infrastructures sportives , Par MM. Jean-Marc TODESCHINI et Dominique BAILLY, Sénateurs. (1) Cette commission est composée de : Mme Marie-Christine Blandin , présidente ; MM. Jean-Étienne Antoinette, David Assouline, Mme Françoise Cartron, M. Ambroise Dupont, Mme Brigitte Gonthier-Maurin, M. Jacques Legendre, Mmes Colette Mélot, Catherine Morin-Desailly, M. Jean-Pierre Plancade , vice-présidents ; Mme Maryvonne Blondin, M. Louis Duvernois, Mme Claudine Lepage, M. Pierre Martin, Mme Sophie Primas, secrétaires ; MM. Serge Andreoni, Maurice Antiste, Dominique Bailly, Pierre Bordier, Mme Corinne Bouchoux, MM. Jean Boyer, Jean-Claude Carle, Jean-Pierre Chauveau, Jacques Chiron, Mme Marie-Annick Duchêne, MM. Alain Dufaut, Jean-Léonce Dupont, Vincent Eblé, Mmes Jacqueline Farreyrol, Françoise Férat, MM. Gaston Flosse, Bernard Fournier, André Gattolin, Jean-Claude Gaudin, Mmes Samia Ghali, Dominique Gillot, Sylvie Goy-Chavent, MM. François Grosdidier, Jean-François Humbert, Mmes Bariza Khiari, Françoise Laborde, M. Pierre Laurent, Mme Françoise Laurent-Perrigot, MM. Jean-Pierre Leleux, Michel Le Scouarnec, Jean-Jacques Lozach, Philippe Madrelle, Jacques-Bernard Magner, Mme Danielle Michel, MM. Philippe Nachbar, Daniel Percheron, Marcel Rainaud, Michel Savin, Abdourahamane Soilihi, Alex Türk, Hilarion Vendegou et Maurice Vincent. (2) Cette commission est composée de : M. Philippe Marini , président ; M. François Marc, rapporteur général ; Mme Michèle André, première vice-présidente ; Mme Marie-France Beaufils, MM. Jean-Pierre Caffet, Yvon Collin, Mme Frédérique Espagnac, M.