Wishing on Dandelions a Novel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Childhood Professionals and Changing Families

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 289 609 PS 017 043 AUTHOR Weiss, Heather B. TITLE Early Childhood Professionals and Changing Families. PUB DATE 10 Apr 87 NOTE 22p.; Paper presented at the Meeting of the Anchorage Association for the Education of Young Children (Anchorage, AK, April 10, 1987). PUB TYPE Viewpoints (120) -- Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Child Caregivers; *Community Action; Early Childhood Education; *Family Programs; Parent Teacher Cooperation; *Preschool Teachers; *Program Implementation; *Public Policy IDENTIFIERS *Alaska; Research Results ABSTRACT Early childl-ood educators are advised to confront difficulties arising from Alaska's economic problems by establishing coalitions between families with young children and service providers, with the intention of creating new programs and maintaining existing family support and education programs. Evidence of the desirability of a wide range of family-provider partnerships is summarized in:(1) discussions of the appeal of such programs from the perspective of public policy; and (2) reports of findings from research and evaluation studies of program effectiveness and the role of social support in child rearing. Subsequent discussion describes desired features of such coalitions and specifies key principles that und.rlie them. Ihe concluding section of the presentation details a research-based plan which conference participants might (evelop to implement partnership programs on a pilot basis, (RH) *********************************************************************** -

January 1988

VOLUME 12, NUMBER 1, ISSUE 99 Cover Photo by Lissa Wales Wales PHIL GOULD Lissa In addition to drumming with Level 42, Phil Gould also is a by songwriter and lyricist for the group, which helps him fit his drums into the total picture. Photo by Simon Goodwin 16 RICHIE MORALES After paying years of dues with such artists as Herbie Mann, Ray Barretto, Gato Barbieri, and the Brecker Bros., Richie Morales is getting wide exposure with Spyro Gyra. by Jeff Potter 22 CHICK WEBB Although he died at the age of 33, Chick Webb had a lasting impact on jazz drumming, and was idolized by such notables as Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich. by Burt Korall 26 PERSONAL RELATIONSHIPS The many demands of a music career can interfere with a marriage or relationship. We spoke to several couples, including Steve and Susan Smith, Rod and Michele Morgenstein, and Tris and Celia Imboden, to find out what makes their relationships work. by Robyn Flans 30 MD TRIVIA CONTEST Win a Yamaha drumkit. 36 EDUCATION DRIVER'S SEAT by Rick Mattingly, Bob Saydlowski, Jr., and Rick Van Horn IN THE STUDIO Matching Drum Sounds To Big Band 122 Studio-Ready Drums Figures by Ed Shaughnessy 100 ELECTRONIC REVIEW by Craig Krampf 38 Dynacord P-20 Digital MIDI Drumkit TRACKING ROCK CHARTS by Bob Saydlowski, Jr. 126 Beware Of The Simple Drum Chart Steve Smith: "Lovin", Touchin', by Hank Jaramillo 42 Squeezin' " NEW AND NOTABLE 132 JAZZ DRUMMERS' WORKSHOP by Michael Lawson 102 PROFILES Meeting A Piece Of Music For The TIMP TALK First Time Dialogue For Timpani And Drumset FROM THE PAST by Peter Erskine 60 by Vic Firth 104 England's Phil Seamen THE MACHINE SHOP by Simon Goodwin 44 The Funk Machine SOUTH OF THE BORDER by Clive Brooks 66 The Merengue PORTRAITS 108 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC by John Santos Portinho A Little Can Go Long Way CONCEPTS by Carl Stormer 68 by Rod Morgenstein 80 Confidence 116 NEWS by Roy Burns LISTENER'S GUIDE UPDATE 6 Buddy Rich CLUB SCENE INDUSTRY HAPPENINGS 128 by Mark Gauthier 82 Periodic Checkups 118 MASTER CLASS by Rick Van Horn REVIEWS Portraits In Rhythm: Etude #10 ON TAPE 62 by Anthony J. -

Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the Rise of the Cäcilien-Verein

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2020 Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the rise of the Cäcilien-Verein Nicholas Bygate Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Bygate, Nicholas, "Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the rise of the Cäcilien-Verein" (2020). WWU Graduate School Collection. 955. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/955 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the rise of the Cäcilien-Verein By Nicholas Bygate Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music ADVISORY COMMITTEE Chair, Dr. Bertil van Boer Dr. Timothy Fitzpatrick Dr. Ryan Dudenbostel GRADUATE SCHOOL David L. Patrick, Interim Dean Master’s Thesis In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non- exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. I warrant that I have obtained written permissions from the owner of any third party copyrighted material included in these files. -

Rubieże Kultury Popularnej

rubieże kultury popularnej Anna Nacher Rubieże kultury popularnej Popkultura w świecie przepływów recenzje anna nacher prof. dr hab. Eugeniusz Wilk prof. UAM dr hab. Marek Krajewski redakcja Karolina Sikorska ilustracje Paulina Płachecka projekt & opracowanie graficzne Magdalena Heliasz rubieże (txt publishing) copyright by Anna Nacher Galeria Miejska Arsenał druk Zakład Poligraficzny Moś i Łuczak, Poznań ISBN 978-83-61886-36-5 kultury wydawca Galeria Miejska Arsenał Stary Rynek 6 61-772 Poznań www.arsenal.art.pl dyrektor Wojciech Makowiecki partnerzy medialni kultura popularna popularnej popkultura w świecie przepływów Dofinansowano ze środków Ministra Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego Galeria Miejska Arsenał Poznań, 2012 – spis treści 10 212 Wstęp Rozdział szósty Rubieże kultury popularnej: Kontrkultury mediosfery między sceną a akademią – cyberaktywizm 28 242 Rozdział pierwszy Rozdział siódmy Taneczny culture jamming Kontrkultury substancji – pogranicza ciała – od halucynogenów do enteogenów 62 Rozdział drugi 282 PKP – polityczna kultura Rozdział ósmy popularna: od centrali do Kontrkultury czasu prowincji i z powrotem – kultura typu slow 92 306 Rozdział trzeci Rozdział dziewiąty Etnowyprzedaż? Miejskie ogrody Etnomuzykologia, world music albo miasto-ogród i Murzynek Bambo po partyzancku 146 338 Rozdział czwarty Rozdział dziesiąty Między eco-chic, Rewolucja ubrana w gadżety projektowaniem zaangażowanym albo wyblakły urok a ekokiczem hipsterstwa – ekologia jako styl życia 360 176 Bibliografia Rozdział piąty Kontrkultury mediosfery 388 – media taktyczne Appendix Rubieże kultury popularnej – między sceną a akademią 10 Rubieże kultury popularnej – między sceną a akademią 1111 wstęp Rubieże kultury popularnej – między sceną a akademią Kiedy otrzymałam propozycję poprowadzenia cyklu wy- kładów w poznańskiej Galerii Miejskiej Arsenał, poświęconych „rubieżom kultury popularnej”, porwała mnie fala entuzjazmu. Im bliżej było jednak pierwszego spotkania, tym wyraźniej mnożyły się wątpliwości. -

2. Do Plant Have to Eat? 3. Everything Gets Split up 4

A.1.10 16 MM FILMS 1. Did Someone Say Cold Blooded? 2. Do Plant Have to Eat? 3. Everything Gets Split Up 4. Some Place for Everything 5. Sunlight In Our Lives 6. What Goes Up In Smoke 7. Things With A Lot Of Pick-up 8. Up From The Valleys 9. What Good Are Electrons A.1.11 SLIDES 1. Eskaya 2. Humanities 3. Picasso Paintings 4. Voyager 1 Encounters Saturn 5. Abortion How It Is? 6. Christ in Prophecy 7. Christmas Is 8. Great Thanksgiving 9. Mysteries of the Rosary 10. Nasa Dios Ang Awa, Nasa Tao Ang Gawa 11. Qou Vadis 12. Religious Vocation 13. Thy Kingdome Come 14. Till Death Do Us Part 15. What Is Retreat? 16. Filing Secretary 17. Divine Word College Library 18. SVD 75 Years 19. God Helps people 20. Huwag Kang Papatay 21. Love (1 Corinthian) 22. Marriage 23. Reaching You 24. The Way 30 A.1.12 TRANSPARENCIES 1. Animal Structure Part 1 & 2 2. Human Structure Part 1 & 2 3. Plant Structure Part 1 & 2 4. Animal Resources 5. Our Plant Resources 6. Our Water Resources 7. Soil Resources 8. The LAND That 9. Problem of Air Pollution 10. Problem of Erosion 11. Problem of Noise Pollution 12. Problem of Water Pollution 13. Basic Writing 14. Chemical Bonding 15. Geologic Formation and Processes 16. Star Constellation Recognition 17. The Earth 18. The Moon 19. Weather 20. Filing for Secretary 21. Marketing 22. Financial Accounting 23. Clothing 24. Food A.1.13 CASSETTE TAPES Successful Achievement Program. Narrated by Gene McKay. -

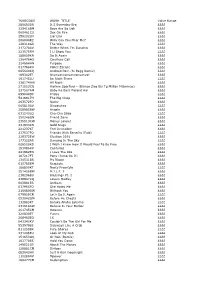

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 289693DR

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 060461CU Sex On Fire ££££ 258202LN Liar Liar ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 217278AV Better When I'm Dancing ££££ 223575FM I Ll Show You ££££ 188659KN Do It Again ££££ 136476HS Courtesy Call ££££ 224684HN Purpose ££££ 017788KU Police Escape ££££ 065640KQ Android Porn (Si Begg Remix) ££££ 189362ET Nyanyanyanyanyanyanya! ££££ 191745LU Be Right There ££££ 236174HW All Night ££££ 271523CQ Harlem Spartans - (Blanco Zico Bis Tg Millian Mizormac) ££££ 237567AM Baby Ko Bass Pasand Hai ££££ 099044DP Friday ££££ 5416917H The Big Chop ££££ 263572FQ Nasty ££££ 065810AV Dispatches ££££ 258985BW Angels ££££ 031243LQ Cha-Cha Slide ££££ 250248GN Friend Zone ££££ 235513CW Money Longer ££££ 231933KN Gold Slugs ££££ 221237KT Feel Invincible ££££ 237537FQ Friends With Benefits (Fwb) ££££ 228372EW Election 2016 ££££ 177322AR Dancing In The Sky ££££ 006520KS I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free ££££ 153086KV Centuries ££££ 241982EN I Love The 90s ££££ 187217FT Pony (Jump On It) ££££ 134531BS My Nigga ££££ 015785EM Regulate ££££ 186800KT Nasty Freestyle ££££ 251426BW M.I.L.F. $ ££££ 238296BU Blessings Pt. 1 ££££ 238847KQ Lovers Medley ££££ 003981ER Anthem ££££ 037965FQ She Hates Me ££££ 216680GW Without You ££££ 079929CR Let's Do It Again ££££ 052042GM Before He Cheats ££££ 132883KT Baraka Allahu Lakuma ££££ 231618AW Believe In Your Barber ££££ 261745CM Ooouuu ££££ 220830ET Funny ££££ 268463EQ 16 ££££ 043343KV Couldn't Be The Girl -

WARNER BROS. / WEA RECORDS 1970 to 1982

AUSTRALIAN RECORD LABELS WARNER BROS. / WEA RECORDS 1970 to 1982 COMPILED BY MICHAEL DE LOOPER © BIG THREE PUBLICATIONS, APRIL 2019 WARNER BROS. / WEA RECORDS, 1970–1982 A BRIEF WARNER BROS. / WEA HISTORY WIKIPEDIA TELLS US THAT... WEA’S ROOTS DATE BACK TO THE FOUNDING OF WARNER BROS. RECORDS IN 1958 AS A DIVISION OF WARNER BROS. PICTURES. IN 1963, WARNER BROS. RECORDS PURCHASED FRANK SINATRA’S REPRISE RECORDS. AFTER WARNER BROS. WAS SOLD TO SEVEN ARTS PRODUCTIONS IN 1967 (FORMING WARNER BROS.-SEVEN ARTS), IT PURCHASED ATLANTIC RECORDS AS WELL AS ITS SUBSIDIARY ATCO RECORDS. IN 1969, THE WARNER BROS.-SEVEN ARTS COMPANY WAS SOLD TO THE KINNEY NATIONAL COMPANY. KINNEY MUSIC INTERNATIONAL (LATER CHANGING ITS NAME TO WARNER COMMUNICATIONS) COMBINED THE OPERATIONS OF ALL OF ITS RECORD LABELS, AND KINNEY CEO STEVE ROSS LED THE GROUP THROUGH ITS MOST SUCCESSFUL PERIOD, UNTIL HIS DEATH IN 1994. IN 1969, ELEKTRA RECORDS BOSS JAC HOLZMAN APPROACHED ATLANTIC'S JERRY WEXLER TO SET UP A JOINT DISTRIBUTION NETWORK FOR WARNER, ELEKTRA, AND ATLANTIC. ATLANTIC RECORDS ALSO AGREED TO ASSIST WARNER BROS. IN ESTABLISHING OVERSEAS DIVISIONS, BUT RIVALRY WAS STILL A FACTOR —WHEN WARNER EXECUTIVE PHIL ROSE ARRIVED IN AUSTRALIA TO BEGIN SETTING UP AN AUSTRALIAN SUBSIDIARY, HE DISCOVERED THAT ONLY ONE WEEK EARLIER ATLANTIC HAD SIGNED A NEW FOUR-YEAR DISTRIBUTION DEAL WITH FESTIVAL RECORDS. IN MARCH 1972, KINNEY MUSIC INTERNATIONAL WAS RENAMED WEA MUSIC INTERNATIONAL. DURING THE 1970S, THE WARNER GROUP BUILT UP A COMMANDING POSITION IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY. IN 1970, IT BOUGHT ELEKTRA (FOUNDED BY HOLZMAN IN 1950) FOR $10 MILLION, ALONG WITH THE BUDGET CLASSICAL MUSIC LABEL NONESUCH RECORDS. -

Welcome, We Have Been Archiving This Data for Research and Preservation of These Early Discs. ALL MP3 Files Can Be Sent to You B

Welcome, To our MP3 archive section. These listings are recordings taken from early 78 & 45 rpm records. We have been archiving this data for research and preservation of these early discs. ALL MP3 files can be sent to you by email - $2.00 per song Scroll until you locate what you would like to have sent to you, via email. If you don't use Paypal you can send payment to us at: RECORDSMITH, 2803 IRISDALE AVE RICHMOND, VA 23228 Order by ARTIST & TITLE [email protected] S.O.S. Band - Finest, The 1983 S.O.S. Band - Just Be Good To Me 1984 S.O.S. Band - Just The Way You Like It 1980 S.O.S. Band - Take Your Time (Do It Right) 1983 S.O.S. Band - Tell Me If You Still Care 1999 S.O.S. Band with UWF All-Stars - Girls Night Out S.O.U.L. - On Top Of The World 1992 S.O.U.L. S.Y.S.T.E.M. with M. Visage - It's Gonna Be A Love. 1995 Saadiq, Raphael - Ask Of You 1999 Saadiq, Raphael with Q-Tip - Get Involved 1981 Sad Cafe - La-Di-Da 1979 Sad Cafe - Run Home Girl 1996 Sadat X - Hang 'Em High 1937 Saddle Tramps - Hot As I Am 1937 (Voc 3708) Saddler, Janice & Jammers - My Baby's Coming Home To Stay 1993 Sade - Kiss Of Life 1986 Sade - Never As Good As The First Time 1992 Sade - No Ordinary Love 1988 Sade - Paradise 1985 Sade - Smooth Operator 1985 Sade - Sweetest Taboo, The 1985 Sade - Your Love Is King Sadina - It Comes And Goes 1966 Sadler, Barry - A Team 1966 Sadler, Barry - Ballad Of The Green Berets 1960 Safaris - Girl With The Story In Her Eyes 1960 Safaris - Image Of A Girl 1963 Safaris - Kick Out 1988 Sa-Fire - Boy, I've Been Told 1989 Sa-Fire - Gonna Make it 1989 Sa-Fire - I Will Survive 1991 Sa-Fire - Made Up My Mind 1989 Sa-Fire - Thinking Of You 1983 Saga - Flyer, The 1982 Saga - On The Loose 1983 Saga - Wind Him Up 1994 Sagat - (Funk Dat) 1977 Sager, Carol Bayer - I'd Rather Leave While I'm In Love 1977 1981 Sager, Carol Bayer - Stronger Than Before 1977 Sager, Carol Bayer - You're Moving Out Today 1969 Sagittarius - In My Room 1967 Sagittarius - My World Fell Down 1969 Sagittarius (feat. -

Ged® Test Reasoning Through Language Arts (Rla) Review

GED® TEST REASONING THROUGH LANGUAGE ARTS (RLA) REVIEW GED_RLA_00_FM_i-x.indd 1 2/29/16 3:21 PM Other titles of interest from LearningExpress GED® Test Preparation GED® Test Mathematical Reasoning Review ® GED Test Flash Review: Mathematical Reasoning ® GED Test Flash Review: Reasoning through Language Arts ® GED Test Flash Review: Science ® GED Test Flash Review: Social Studies GED_RLA_00_FM_i-x.indd 2 2/29/16 3:21 PM GED® TEST REASONING THROUGH LANGUAGE ARTS (RLA) REVIEW ® NEW YORK GED_RLA_00_FM_i-x.indd 3 2/29/16 3:21 PM Copyright © 2016 LearningExpress. All rights reserved under International and Pan American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by LearningExpress, New York. ISBN-13: 978-1-61103-048-8 Printed in the United States of America 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For more information on LearningExpress, other LearningExpress products, or bulk sales, please write to us at: 224 W. 29th Street 3rd Floor New York, NY 10001 GED_RLA_00_FM_i-x.indd 4 2/29/16 3:21 PM CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 Introduction to the GED® RLA Test 1 About the GED® RLA Test 2 Question Types 2 How to Use This Book 7 Test Taking Tips 7 Eliminating Answer Choices 9 Keeping Track of Time 10 Preparing for the Test 11 The Big Day 12 Good Luck! 12 CHAPTER 2 Diagnostic Test 13 Part I 17 Part II 29 Answers and Explanations 30 CHAPTER 3 Reading Comprehension: Big Picture Tools 37 Reading the Passages 38 Tips for Fiction Passages 40 Tips for Nonfiction Passages 41 Author’s Purpose 42 Point of View 45 Theme 47 Synthesis 51 Reading More Closely 55 v GED_RLA_00_FM_i-x.indd -

Ireland Into the Mystic: the Poetic Spirit and Cultural Content of Irish Rock

IRELAND INTO THE MYSTIC: THE POETIC SPIRIT AND CULTURAL CONTENT OF IRISH ROCK MUSIC, 1970-2020 ELENA CANIDO MUIÑO Doctoral Thesis / 2020 Director: David Clark Mitchell PROGRAMA DE DOCTORADO EN ESTUDIOS INGLESES AVANZADOS: LENGUA, LITERATURA Y CULTURA Ireland into the Mystic: The Poetic Spirit and Cultural Content of Irish Rock Music, 1970-2020 by Elena Canido Muiño, 2020. INDEX Abstract .......................................................................................................................... viii Resumen .......................................................................................................................... ix Resumo ............................................................................................................................. x 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 1.1.1. Methodology ................................................................................................................. 3 1.1.2. Thesis Structure ............................................................................................................. 5 2. Historical and Theoretical Introduction to Irish Rock ........................................ 9 2.1.1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 9 2.1.2. The Origins of Rock ...................................................................................................... 9 2.1.3. -

Stephen Stills Discography Music

Stephen stills discography music Find Stephen Stills discography, albums and singles on AllMusic. and Crosby, Stills & Nash, two of pop music's most successful and enduring groups. Stephen Stills discography and songs: Music profile for Stephen Stills, born January 3, Albums include Super Session, Manassas, and Stephen Stills. Stephen Stills Has a Message for Donald Trump. Hear "Look Each Other In The Eye," a song that rails against Republican candidate Donald Trump's vanity and Stephen Stills Has a Message · Stephen Stills And Judy · Tour Dates · News. Ultimate Classic Rock counts down the best solo songs by Stephen Stills. Still, as you'll see in a list of Top 10 Stephen Stills Songs which steers .. From: 'Stephen Stills 2′ () . It's not “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes,” but it's as close as Stills gets without help from his .. The Most Inflluential Grunge Albums. List of the best Stephen Stills albums, including pictures of the album covers when av music The Best Stephen Stills Albums of All Time 3. 8 1. Stephen Stills 2 is listed (or ranked) 3 on the list The Best Stephen Super Session Stephen Stills, Mike Bloomfield, Al Kooper Just Roll Tape- April 26th, Stephen Stills. Church (part of someone) 4. Old times Music. "Love The One You're With" by Stephen Stills. Visit 's Stephen Stills Store to shop for Stephen Stills albums (CD, MP3, Vinyl), concert tickets, and other Stephen Stills-related products (DVDs, Books, T-shirts). Also explore Digital Music. Select the .. Stephen Stills 2. Stephen Stills . by Stephen Stills on Just Roll Tape - April 26th · Treetop Flyer. -

Lp Stock Database

Excluding Children, Classical/Ballet/ Opera, Religious Vinyl 4U Main Database (see other databases for these) 1 LP (x1) 2 Contact: Judy Vos [email protected] LP's (x2) # of LPs in Artist/s or Group Composer Album Name Album 101 Strings After a hard day x1 101 Strings Lerner&Loewe Camelot x1 101 Strings Exodus and other great movie themes x1 101 Strings Webb/BacharachMillion Seller Hits x1 10CC Bloody Tourists x1 ABBA Arrival x1 ABBA Gracias por la Musica x1 ABBA Gracias por la musica (in Spanish) x1 ABBA Greatest Hits x1 ABBA Greatest Hits x1 ABBA Greatest Hits x1 ABBA Greatest Hits x1 ABBA Greatest Hits x1 ABBA Super Trouper x1 ABBA Super Trouper x1 ABBA Super Trouper x1 ABBA Super Trouper x1 ABBA The Album x1 ABBA The Album x1 Abba The Album x1 ABBA The Singles - The 1st 10 years x2 ABBA The Visitors x1 ABBA The Visitors x1 ABBA The Visitors x1 ABBA The Visitors x1 ABBA The Visitors x1 ABBA Voulez Vouz x1 ABBA Voulez-Vous x1 ABBA Voulez-Vous x1 ABBA Voulez-Vous x1 ABC Beauty Stab x1 Acker Bilk Stranger on the shore x1 Acker Bilk & Bent Fabric Cocktails for Two x1 Acker Bilk & others Clarinet Jamboree x1 Acker Bilk & Stan Tracey Blue Acker x1 Acker Bilk Esquire A Taste of honey x1 Acker Bilk with Leon Young Stranger on the Shore x1 Adam and the Ants Kings of the Wild Frontier x1 Adam and The Beasts Alasdair Clayre x1 Adamo A L'Olympia x1 Adamo Adamo x1 Adamo The Hits of Adamo x1 Adrian Brett Echoes of Gold x1 Adrian Gurvitz Classic x1 Agnetha Faltskog Eyes of a woman x1 Agnetha Faltskog Wrap your arms around me x1 A-Ha Stay on these