CAPSTONE 20-1 SWA Field Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Newsletter on Kazakhstan |October 2020

Economic Newsletter on Kazakhstan |October 2020 CONTENTS MACRO-ECONOMICS & FINANCE ..................................................................................... 2 ENERGY & NATURAL RESOURCES ..................................................................................... 6 TRANSPORT & COMMUNICATIONS ................................................................................ 10 AGRICULTURE ................................................................................................................. 12 CONTACTS ...................................................................................................................... 16 The Economic Section of the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Kazakhstan intends to distribute this newsletter as widely as possible among Dutch institutions, companies and persons from the Netherlands. The newsletter summarises economic news from various Kazakhstani and foreign publications and aims to provide accurate information. However, the Embassy cannot be held responsible for any mistakes or omissions in the bulletin. ECONOMIC NEWSLETTER, October 2020 Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Kazakhstan MACRO-ECONOMICS & FINANCE Council for Improving Investment Climate considers prospects for economic recovery At a meeting of the Council for Improving the Investment Climate chaired by Prime Minister Askar Mamin, issues of economic recovery in Kazakhstan in the post-pandemic period were considered. Ambassadors accredited in the country of the US William Moser, of the UK -

11 an Analysis of the Internal Structure of Kazakhstan's Political

11 Dosym SATPAEV An Analysis of the Internal Structure of Kazakhstan’s Political Elite and an Assessment of Political Risk Levels∗ Without understating the distinct peculiarities of Kazakhstan’s political development, it must be noted that the republic’s political system is not unique. From the view of a typology of political regimes, Kazakhstan possesses authoritarian elements that have the same pluses and minuses as dozens of other, similar political systems throughout the world. Objectivity, it must be noted that such regimes exist in the majority of post-Soviet states, although there has lately been an attempt by some ideologues to introduce terminological substitutes for authoritarianism, such as with the term “managed democracy.” The main characteristic of most authoritarian systems is the combina- tion of limited pluralism and possibilities for political participation with the existence of a more or less free economic space and successful market reforms. This is what has been happening in Kazakhstan, but it remains ∗ Editor’s note: The chapter was written in 2005, and the information contained here has not necessarily been updated. Personnel changes in 2006 and early 2007 include the fol- lowing: Timur Kulibaev became vice president of Samruk, the new holding company that manages the state shares of KazMunayGas and other top companies; Kairat Satybaldy is now the leader of the Muslim movement “Aq Orda”; Nurtai Abykaev was appointed am- bassador to Russia; Bulat Utemuratov became presidential property manager; and Marat Tazhin was appointed minister of foreign affairs. 283 Dosym SATPAEV important to determine which of the three types of authoritarian political systems—mobilized, conservative, or modernizing (that is, capable of political reform)—exists in Kazakhstan. -

Kazakhstan Completes Three-Year, EU-Backed Project to Reform

+13° / +4°C WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 10, 2018 No 19 (157) www.astanatimes.com President focuses on improving daily Astana to host Sixth Congress life in state-of-nation address of Leaders of World and Traditional Religions of World and Traditional religions Staff Report took place Sept. 23-24, 2003 at the initiative of Kazakh President Nur- ASTANA – Eighty-two del- sultan Nazarbayev. egations from 46 countries repre- Its objectives are to seek uni- senting the world’s religions are versal guidelines among world expected to gather in Astana Oct. and traditional religions and to be 10-11 for the Sixth Congress of a permanent platform for interna- Leaders of World and Traditional tional interfaith dialogue. Religions. The main priorities of the congress The Congress is to be held under are to promote peace, harmony and the subject of “Religious Leaders tolerance as the unshakable princi- for a Secure World” and will in- ples of human existence, to achieve clude the third session of its Coun- mutual respect and tolerance among cil of Religious Leaders. religions and ethnic groups, as well Religious leaders, religious or- as to prevent religious beliefs from ganisations and political repre- being used to fuel the escalation of sentatives are expected to discuss conflicts and military action. four topics: A specially designed C Section – The manifesto “The World. of this issue will offer our read- The 21st Century’ as a “concept of ers more in-depth information global security.” about the Congress of Leaders of – Religions in changing geopoli- World and Traditional Religions, tics: new opportunities for the con- its history and activities, as well solidation of humankind. -

Engaging Central Asia

ENGAGING CENTRAL ASIA ENGAGING CENTRAL ASIA THE EUROPEAN UNION’S NEW STRATEGY IN THE HEART OF EURASIA EDITED BY NEIL J. MELVIN CONTRIBUTORS BHAVNA DAVE MICHAEL DENISON MATTEO FUMAGALLI MICHAEL HALL NARGIS KASSENOVA DANIEL KIMMAGE NEIL J. MELVIN EUGHENIY ZHOVTIS CENTRE FOR EUROPEAN POLICY STUDIES BRUSSELS The Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) is an independent policy research institute based in Brussels. Its mission is to produce sound analytical research leading to constructive solutions to the challenges facing Europe today. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors writing in a personal capacity and do not necessarily reflect those of CEPS or any other institution with which the authors are associated. This study was carried out in the context of the broader work programme of CEPS on European Neighbourhood Policy, which is generously supported by the Compagnia di San Paolo and the Open Society Institute. ISBN-13: 978-92-9079-707-4 © Copyright 2008, Centre for European Policy Studies. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior permission of the Centre for European Policy Studies. Centre for European Policy Studies Place du Congrès 1, B-1000 Brussels Tel: 32 (0) 2 229.39.11 Fax: 32 (0) 2 219.41.51 e-mail: [email protected] internet: http://www.ceps.eu CONTENTS 1. Introduction Neil J. Melvin ................................................................................................. 1 2. Security Challenges in Central Asia: Implications for the EU’s Engagement Strategy Daniel Kimmage............................................................................................ -

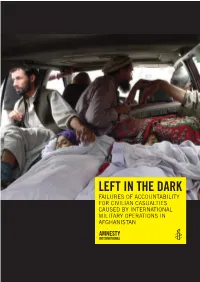

Left in the Dark

LEFT IN THE DARK FAILURES OF ACCOUNTABILITY FOR CIVILIAN CASUALTIES CAUSED BY INTERNATIONAL MILITARY OPERATIONS IN AFGHANISTAN Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: ASA 11/006/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Bodies of women who were killed in a September 2012 US airstrike are brought to a hospital in the Alingar district of Laghman province. © ASSOCIATED PRESS/Khalid Khan amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF AFGHANISTAN .......................................................................................... 6 1. SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 7 Methodology .......................................................................................................... -

In This Issue

VOLUME VII, ISSUE 36 u NOVEMBER 25, 2009 IN THIS ISSUE: BRIEFS...................................................................................................................................1 IBRAHIM AL-RUBAISH: NEW RELIGIOUS IDEOLOGUE OF AL-QAEDA IN SAUDI ARABIA CALLS FOR REVIVAL OF ASSASSINATION TACTIC By Murad Batal al-Shishani..................................................................................................3 AL-QAEDA IN IRAQ OPERATIONS SUGGEST RISING CONFIDENCE AHEAD OF U.S. MILITARY WITHDRAWAL Al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) By Ramzy Mardini..........................................................................................................4 FRENCH OPERATION IN AFGHANISTAN AIMS TO OPEN NEW COALITION SUPPLY ROUTE Terrorism Monitor is a publication By Andrew McGregor............................................................................................................6 of The Jamestown Foundation. The Terrorism Monitor is TALIBAN EXPAND INSURGENCY TO NORTHERN AFGHANISTAN designed to be read by policy- makers and other specialists By Wahidullah Mohammad.................................................................................................9 yet be accessible to the general public. The opinions expressed within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily LEADING PAKISTANI ISLAMIST ORGANIZING POPULAR MOVEMENT reflect those of The Jamestown AGAINST SOUTH WAZIRISTAN OPERATIONS Foundation. As the Pakistani Army pushes deeper into South Waziristan, a vocal political Unauthorized reproduction or challenge -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Logic of Kleptocracy: Corruption, Repression, and Political Opposition in Post-Soviet Eurasia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/92g1h187 Author LaPorte, Jody Marie Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Logic of Kleptocracy: Corruption, Repression, and Political Opposition in Post-Soviet Eurasia By Jody Marie LaPorte A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Jason Wittenberg, Co-chair Professor Michael S. Fish, Co-chair Professor David Collier Professor Victoria Bonnell Spring 2012 The Logic of Kleptocracy: Corruption, Repression, and Political Opposition in Post-Soviet Eurasia Copyright 2012 by Jody Marie LaPorte Abstract The Logic of Kleptocracy: Corruption, Repression, and Political Opposition in Post-Soviet Eurasia by Jody Marie LaPorte Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Jason Wittenberg, co-chair Professor Michael S. Fish, co-chair This dissertation asks why some non-democratic regimes give political opponents significant leeway to organize, while others enforce strict limits on such activities. I examine this question with reference to two in-depth case studies from post-Soviet Eurasia: Georgia under President Eduard Shevardnadze and Kazakhstan under President Nursultan Nazarbayev. While a non- democratic regime was in place in both countries, opposition was highly tolerated in Georgia, but not allowed in Kazakhstan. I argue that these divergent policies can be traced to variation in the predominant source and pattern of state corruption in each country. -

Afghanistan Security Situation in Nangarhar Province

Report Afghanistan: The security situation in Nangarhar province Translation provided by the Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, Belgium. Report Afghanistan: The security situation in Nangarhar province LANDINFO – 13 OCTOBER 2016 1 About Landinfo’s reports The Norwegian Country of Origin Information Centre, Landinfo, is an independent body within the Norwegian Immigration Authorities. Landinfo provides country of origin information to the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (Utlendingsdirektoratet – UDI), the Immigration Appeals Board (Utlendingsnemnda – UNE) and the Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security. Reports produced by Landinfo are based on information from carefully selected sources. The information is researched and evaluated in accordance with common methodology for processing COI and Landinfo’s internal guidelines on source and information analysis. To ensure balanced reports, efforts are made to obtain information from a wide range of sources. Many of our reports draw on findings and interviews conducted on fact-finding missions. All sources used are referenced. Sources hesitant to provide information to be cited in a public report have retained anonymity. The reports do not provide exhaustive overviews of topics or themes, but cover aspects relevant for the processing of asylum and residency cases. Country of origin information presented in Landinfo’s reports does not contain policy recommendations nor does it reflect official Norwegian views. © Landinfo 2017 The material in this report is covered by copyright law. Any reproduction or publication of this report or any extract thereof other than as permitted by current Norwegian copyright law requires the explicit written consent of Landinfo. For information on all of the reports published by Landinfo, please contact: Landinfo Country of Origin Information Centre Storgata 33A P.O. -

Uzbekistan: Recent Developments and U.S

Order Code RS21238 Updated May 2, 2005 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Uzbekistan: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests Jim Nichol Specialist in Russian and Eurasian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Summary Uzbekistan is an emerging Central Asian regional power by virtue of its relatively large population, energy and other resources, and location in the heart of the region. It has made limited progress in economic and political reforms, and many observers criticize its human rights record. This report discusses U.S. policy and assistance. Basic facts and biographical information are provided. This report may be updated. Related products include CRS Issue Brief IB93108, Central Asia, updated regularly. U.S. Policy1 According to the Administration, Uzbekistan is a “key strategic partner” in the Global War on Terrorism and “one of the most influential countries in Central Asia.” However, Uzbekistan’s poor record on human rights, democracy, and religious freedom complicates its relations with the United States. U.S. assistance to Uzbekistan seeks to enhance the sovereignty, territorial integrity, and security of Uzbekistan; diminish the appeal of extremism by strengthening civil society and urging respect for human rights; bolster the development of natural resources such as oil; and address humanitarian needs (State Department, Congressional Presentation for Foreign Operations for FY2006). Because of its location and power potential, some U.S. policymakers argue that Uzbekistan should receive the most U.S. attention in the region. 1 Sources for this report include the Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS), Central Eurasia: Daily Report; Eurasia Insight; RFE/RL Central Asia Report; the State Department’s Washington File; and Reuters, Associated Press (AP), and other newswires. -

Kazakhstan by Bhavna Dave

Kazakhstan by Bhavna Dave Capital: Astana Population: 15.9 million GNI/capita, PPP: US$10,320 Source: !e data above was provided by !e World Bank, World Development Indicators 2011. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Electoral Process 6.25 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 Civil Society 5.50 5.50 5.50 5.50 5.75 5.75 5.50 5.50 5.75 5.75 Independent Media 6.00 6.25 6.50 6.50 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.50 6.75 6.75 Governance* 5.75 6.25 6.25 n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a National Democratic 6.75 Governance n/a n/a n/a 6.50 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 Local Democratic 6.25 Governance n/a n/a n/a 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.25 Judicial Framework 6.25 and Independence 6.00 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.00 6.25 Corruption 6.25 6.25 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.50 Democracy Score 5.96 6.17 6.25 6.29 6.39 6.39 6.39 6.32 6.43 6.43 * Starting with the 2005 edition, Freedom House introduced separate analysis and ratings for national democratic governance and local democratic governance to provide readers with more detailed and nuanced analysis of these two important subjects. -

Kazajstán República De Kazajstán

OFICINA DE INFORMACIÓN DIPLOMÁTICA FICHA PAÍS Kazajstán República de Kazajstán La Oficina de Información Diplomática del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores, Unión Europea y Cooperación pone a disposición de los profesionales de los medios de comunicación y del público en general la presente ficha país. La información contenida en esta ficha país es pública y se ha extraído de diversos medios, no defendiendo posición política alguna ni de este Ministerio ni del Gobierno de España respecto del país sobre el que versa. MARZO 2021 reparte entre pequeñas comunidades de judíos, budistas, católicos y testigos Kazajstán de Jehová. Forma de Estado: la Constitución, en vigor desde el 30 de agosto de 1995, establece que Kazajstán es una República unitaria con un régimen presi- dencial. División Administrativa: Kazajstán está dividido administrativamente en 17 RUSIA unidades territoriales: 14 regiones y 3 de “ciudades de importancia repu- Petropavlovsk blicana”. Las 14 regiones (Oblast) son: Akmolinskaya, Aktyubinskaya, Al- Qostanay Pavlodar matinskaya, Atyrauskaya, Kazajstán del Este, Zhambylskaya, Kazajstán del Oral ASTANÁ Oskemen Oeste, Karagandinskaya, Kostanaiskaya, Kyzylordinskaya, Mangistauskaya, Aqtobe Karaganda Pavlodarskaya, Kazajstán del Norte y Turkestán. Las 3 ciudades de impor- tancia republicana son la capital Nur-Sultan, Almaty y Shymkent. También Atyrau el Cosmódromo de Baikonur ostenta un estatuto diferenciado, pues tanto el Lago Balkhash Cosmódromo como sus instalaciones anejas están alquilados a Rusia hasta Baikonur el año 2050. Aqtau Mar Aral 85 inscritos en el Registro de Matrícula Consular (a Almaty Residentes españoles: Mar Caspio UZBEKISTÁN Taraz 16 de febrero de 2021). Shymkent KIRGUISTÁN CHINA TURKMENISTÁN 1.2. Geografía © Ocina de Información Diplomática. Con una superficie de 2.724.900 km2, Kazajstán es el noveno país más Aviso: Las fronteras trazadas no son necesariamente las reconocidas ocialmente. -

Threats and Attacks Against Human Rights Defenders and the Role Of

Uncalculated Risks Threats and attacks against human rights defenders and the role of development financiers Uncalculated Risks Threats and attacks against human rights defenders and the role of development financiers May 2019 This report was authored by With case studies and contributions from And with the generous support of Uncalculated Risks Threats and attacks against human rights defenders and the role of development financiers © Coalition for Human Rights in Development, May 2019 The views expressed herein, and any errors or omissions are solely the author’s. We additionally acknowledge the valuable insights and assistance of Valerie Croft, Amy Ekdawi, Lynne-Samantha Severe, Kendyl Salcito, Julia Miyahara, Héctor Herrera, Spencer Vause, Global Witness, Movimento dos Atingidos por Barragens, and the various participants of the Defenders in Development Campaign in its production. This report is an initiative of the Defenders in Development Campaign which engages in capacity building and collective action to ensure that communities and marginalized groups have the information, resources, protection and power to shape, participate in, or oppose development activities, and to hold development financiers, governments and companies accountable. We utilize advocacy and campaigning to change how development banks and other actors operate and to ensure that they respect human rights and guarantee a safe enabling environment for public participation. More information: www.rightsindevelopment.org/uncalculatedrisks [email protected] This publication is a CC-BY-SA – Attribution-ShareAlike creative commons license – the text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The license holder requests that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes.