The “Double Triangle” Paradigm: National Redemption in Bi-Generational Love Triangles from Agnon to Oz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barriers to Peace in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Founded by the Charles H. Revson Foundation Barriers to Peace in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Editor: Yaacov Bar-Siman-Tov 2010 Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies – Study no. 406 Barriers to Peace in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Editor: Yaacov Bar-Siman-Tov The statements made and the views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors. © Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Israel 6 Lloyd George St. Jerusalem 91082 http://www.kas.de/israel E-mail: [email protected] © 2010, The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies The Hay Elyachar House 20 Radak St., 92186 Jerusalem http://www.jiis.org E-mail: [email protected] This publication was made possible by funds granted by the Charles H. Revson Foundation. In memory of Professor Alexander L. George, scholar, mentor, friend, and gentleman The Authors Yehudith Auerbach is Head of the Division of Journalism and Communication Studies and teaches at the Department of Political Studies of Bar-Ilan University. Dr. Auerbach studies processes of reconciliation and forgiveness . in national conflicts generally and in the Israeli-Palestinian context specifically and has published many articles on this issue. Yaacov Bar-Siman-Tov is a Professor of International Relations at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and holds the Chair for the Study of Peace and Regional Cooperation. Since 2003 he is the Head of the Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies. He specializes in the fields of conflict management and resolution, peace processes and negotiations, stable peace, reconciliation, and the Arab-Israeli conflict in particular. He is the author and editor of 15 books and many articles in these fields. -

The Blue Mountain 1

THE BLUE MOUNTAIN By Meir Shalev Translated by Hillel Halkin First publis hed in Hebrew by Am Oved, 1998 English translation published by Harper Collins, 1991 Study guide by Ilana Kurshan with Adi Inbar ABOUT THE BOOK: This lush and compelling novel is set in a small cooperative village in the Valley of Jezreel prior to the founding of Israel. The earliest inhabitants of the village are Eastern European immigrants who arrived in the early 1900s in what has become known as the Second Aliyah. Their story is narrated by Baruch, the grandson of one of the village founders, who becomes the owner of a cemetery that serves as a resting place for many members of this pioneering generation. Baruch recalls his grandfather Mirkin and his two friends Mandolin Tsirkin and Eliezer Liberson, who, inspired by the beautiful Feyge Levin, formed the Feyge Levin Workingman's Circle, which soon became a village legend. The village is peopled by colorful characters such as Ya'akov Pinnes, a gifted teacher who takes his students out into the fields to infuse them with his love for nature; Uncle Efrayim, who disappears carrying his beloved pet bull named Jean Valjean on his shoulders; and Hayyim Margulis, the beekeeper who allows himself to be seduced by the watchman's wife. Baruch comes to know their stories through conversations with his grandfather and with his teacher Pinnes, and through his own childhood recollections, which are woven together to create a rich and vivid historical tapestry. ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Meir Shalev was born in Israel in 1948, the same year as the founding of the State. -

President's Report 2018

VISION COUNTING UP TO 50 President's Report 2018 Chairman’s Message 4 President’s Message 5 Senior Administration 6 BGU by the Numbers 8 Building BGU 14 Innovation for the Startup Nation 16 New & Noteworthy 20 From BGU to the World 40 President's Report Alumni Community 42 2018 Campus Life 46 Community Outreach 52 Recognizing Our Friends 57 Honorary Degrees 88 Board of Governors 93 Associates Organizations 96 BGU Nation Celebrate BGU’s role in the Israeli miracle Nurturing the Negev 12 Forging the Hi-Tech Nation 18 A Passion for Research 24 Harnessing the Desert 30 Defending the Nation 36 The Beer-Sheva Spirit 44 Cultivating Israeli Society 50 Produced by the Department of Publications and Media Relations Osnat Eitan, Director In coordination with the Department of Donor and Associates Affairs Jill Ben-Dor, Director Editor Elana Chipman Editorial Staff Ehud Zion Waldoks, Jacqueline Watson-Alloun, Angie Zamir Production Noa Fisherman Photos Dani Machlis Concept and Design www.Image2u.co.il 4 President's Report 2018 Ben-Gurion University of the Negev - BGU Nation 5 From the From the Chairman President Israel’s first Prime Minister, David Ben–Gurion, said:“Only Apartments Program, it is worth noting that there are 73 This year we are celebrating Israel’s 70th anniversary and Program has been studied and reproduced around through a united effort by the State … by a people ready “Open Apartments” in Beer-Sheva’s neighborhoods, where acknowledging our contributions to the State of Israel, the the world and our students are an inspiration to their for a great voluntary effort, by a youth bold in spirit and students live and actively engage with the local community Negev, and the world, even as we count up to our own neighbors, encouraging them and helping them strive for a inspired by creative heroism, by scientists liberated from the through various cultural and educational activities. -

ABOUT the BOOK: This Novel Is the Story of Two Great Loves. the First Is

A PIGEON AND A BOY By Meir Shalev Translated by Evan Fallenberg First publis hed in Hebrew by Am Oved, 2006 English translation published by Schocken, 2007 Study guide by Ilana Kurshan ABOUT THE BOOK: This novel is the story of two great loves. The first is the love between a young pigeon handler nicknamed the Baby, and a Girl (as she is known) who works in a Tel Aviv zoo, set in 1948 during Israel’s War for Independence. The second love, which unfolds a generation later, is that between a middle- aged Israeli tour guide named Yair Mendelsohn and his childhood friend Tirzah Fried, who serves as his contractor after his mother bequeaths him money to build a new house apart from his wife. The two loves—past and present—are intertwined with one another from the book’s opening pages, when Yair hears about the young pigeon handler from one of his American clients. The climax of the novel, the pigeon handler’s final hopeful dispatch, brings together this sweeping story about wandering passion and the longing for home. ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Meir Shalev was born in 1948 on Nahalal, Israel’s first moshav, to a family of writers. He studied psychology at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. One of Israel’s most celebrated novelists, his books have been translated into more than twenty languages and have been bestsellers in Israel, Holland, and Germany. In 1999 the author was awarded the Juliet Club Prize (Italy). He has also received the Prime Minister’s Prize (Israel), the Chiavari (Italy), the Entomological Prize (Israel), the WIZO Prize (France, Israel, and Italy), and for A Pigeon and a Boy, the Brenner Prize, Israel’s highest literary recognition. -

Israeli Literature and the American Reader

Israeli Literature and the American Reader by ALAN MINTZ A HE PAST 25 YEARS HAVE BEEN a heady time for lovers of Is- raeli literature. In the 1960s the Israeli literary scene began to explode, especially in terms of fiction. Until then, poetry had been at the center of literary activity. While S.Y. Agnon's eminence, rooted in a different place and time, persisted, the native-born writers who began to produce stories and novels after 1948 never seemed to be able to carry their ef- forts much beyond the struggles and controversies of the hour. Then suddenly there were the short stories of Amos Oz, A.B. Yehoshua, Aharon Appelfeld, and Amalia Kahana-Carmon, followed by their first and second novels. These writers were soon joined by Shulamit Hareven, Yehoshua Kenaz, Yaakov Shabtai, and David Grossman. Into the 1980s and 1990s the debuts of impressive new writers became more frequent, while the productivity of the by-now established ones only intensified. What was different about this new Israeli literature was the quality and inventiveness of its fictional techniques and its ability to explore univer- sal issues in the context of Israeli society. There was also a new audience for this literature; children of immigrants had become sophisticated He- brew readers. Many of the best books became not only critical successes but best-sellers as well. Was this a party to which outsiders were invited? Very few American Jews knew Hebrew well enough to read a serious modern Hebrew book, so that even if they were aware of the celebration, they could not hear the music. -

Minorities in Modern Hebrew Literature: a Survey1

Minorities in Modern Hebrew Literature: A Survey Minorities in Modern Hebrew Literature: A Survey1 近現代ヘブライ文学におけるマイノリティ:概観 Doron B. Cohen, Ph.D. ドロン・B・コヘン,Ph.D. Summary:1 Along their history, Jews often found themselves in a minority situation, and their awareness of this fact was expressed in their writings, but in modern times Jews also experienced being a majority. However, even while being an ethnic minority, they had various groups of social minorities in their midst. The present article offers a survey of the attitude towards various kinds of minorities as expressed in Modern Hebrew literature, along a division to three periods: (1) in Eastern Europe, from mid-19th to early 20th century (minorities such as orphans, the handicapped, and women as marginal- ized in society); (2) in Central Europe and Palestine, during the first half of the 20th century (similar minorities); (3) in the State of Israel (similar minorities, as well as Arabs, Jews of Asian and African origin and migrant workers). Our survey shows that authors of Modern Hebrew literature displayed an acute awareness of the plight of different minorities. Key words: Hebrew Literature, Minorities, Jews & Arabs, Ashkenazim, Mizrahim 要旨: 歴史を通じて、ユダヤ人はしばしばマイノリティの状況にあり、その意識は彼らの書くもの に表現されてきた。しかし、近現代においては、ユダヤ人はマジョリティとしての立場も体 験することになった。民族としてはマイノリティであっても、彼らの内部には様々な社会的 マイノリティ集団を抱えていた。本稿は、近現代ヘブライ文学に表れた様々なマイノリティ への態度を概観するものである。近現代を以下の三つの時期に区分する:(1)19 世紀半ば −20 世紀初頭の東欧(社会の周縁にあるマイノリティとしては、孤児、障がい者、女性な ど )、( 2)20 世紀前半の中央ヨーロッパとパレスティナ地域(同上のマイノリティ)、(3) イスラエル国家において(同上のマイノリティに加えて、アラブ人、アジア系及びアフリカ 系ユダヤ人、移民労働者)。本稿の概観を通して、近現代ヘブライ文学の著者は、様々なマ イノリティの窮状を鋭く認識し、それを表現していたことが窺える。 キーワード: ヘブライ文学、マイノリティ、ユダヤ人とアラブ人、アシュケナジーム、ミズラヒーム 1 I am grateful to Prof. Nitza Ben-Dov of Haifa University for her generous assistance in the writing of this article, but I must obviously assume sole responsibility for any error or misjudgment in it. -

Spring 2013, a Good Deal of It Focused on on Sunday-Monday, March 17-18, Will Shirley Holtzman Israeli Literature Collec- Israel

Michigan State University College of Arts & Letters C-730 Wells Hall 619 Red Cedar Road East Lansing, MI 48824 Telephone: 517-432-3493 Fax: 517-355-4507 Web: jsp.msu.edu E-mail: [email protected] Kenneth Waltzer, Director Spring Semester 2013 Michael Serling, Chair, Advisory Board Bill Bilstad, Newsletter Editor Focus on Israel MSU Jewish Studies has an active schedule The 8th Annual MSU Israeli Film Festival brate the opening of the Irwin T. and in spring 2013, a good deal of it focused on on Sunday-Monday, March 17-18, will Shirley Holtzman Israeli Literature Collec- Israel. Currently, the state that holds the show outstanding recent Israeli films that tion in the MSU Libraries, and is supported largest concentration of Jews in the world have won the Ophir (Israeli’s Academy by a gift from Ritta Rosenberg is going through elections and perhaps, in Award) or other awards. In addition, we This semester, MSU Jewish Studies will the next six months, facing huge existential will also be hosting a second evening with also co-host with James Madison College questions. filmmaker Judith Manassen-Ramon. historian David E. Fishman of the Jewish A debate in the blogosphere asks wheth- The major event of the spring will be Theological Seminary on Wednesday, Feb- er Israel is shifting dramatically to the right our ambitious Symposium on Hebrew and ruary 20, for our annual Yiddishkeit lecture. and the election will be another turning Israeli Literature, April 9-10, 2013. Guest Professor Fishman’s lecture will be on “The point in Israeli history or Israelis are simply speakers will include outstanding Israeli Dynamics of Jewish Life in 1930s Vilna.” reflecting their pessimism about the peace novelist Meir Shalev and the well-known Finally, our 21st annual Rabin Lecture on process while still embracing support for a University of California-Berkeley scholar the Holocaust will be delivered on April 18 two-state solution. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Impulse (Impulse #1) by Ellen Hopkins Bettering Me Up

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Impulse (Impulse #1) by Ellen Hopkins Bettering Me Up. In one instant each of these young people decided enough was enough. They grabbed the blade, the bottle, the gun -- and tried to end it all. Now they have a second chance, and just maybe, with each other's help, they can find their way to a better life -- but only if they're strong and can fight the demons that brought them here in the first place. What can I say about Ellen Hopkins that I haven't already said before? She is brilliant and I can't get enough of her work. She is not afraid to tackle tough issues faced by teenagers and her writing is sublime. Impulse (Impulse #1) by Ellen Hopkins. Pattyn has been raised in a very religious and abusive home where she is not sure what her purpose in life is. She meets a boy and gets in trouble with her parents, who decide to send her to her aunt's house to live. Her summer spent at her aunt's house and the return home is full of eye opening moments and life changing events. "Hopkins’s incisive verses sometimes read in several directions as they paint the beautiful Nevada desert and the consequences of both nuclear testing at Yucca Mountain and Pattyn’s tragic family history." -Kirkus Reviews Ages 14-up. Hopkins, Ellen. Burned . New York: Margaret K. McElderry Books. 2006. Print. "Burned." 2010. Kirkus Reviews & Recommendations . https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/ellen-hopkins/burned/ Accessed April 8, 2013. -

Yonatan Karmon

מגזין לריקודי עם ומחול עמותת ארגון המדריכים והיוצרים לריקודי עם Vol 103 | May 2020 Photo: A, Brener In The Light Of Memories Yonatan Karmon July 28 1931 February 6 2020 Dear Readers, This issue is entirely devoted to the man who molded Israeli folk dance for the stage and who greatly influenced the dances מגזין לריקודי עם ומחול done in dance sessions (harkadot). In recent years, we, the editors of “Rokdim-Nirkoda” magazine, have decided to interview and present articles about important Yaron Meishar עמותת ארגון המדריכים and significant people who have shaped and influenced Israeli והיוצרים לריקודי עם folk dance in the early years of the country (State of Israel). Vol. No. 103 | May 2020 Yonatan is of course, is one of the most notable of them. To Receive This Issue Please Press VIP Therefore, in November 2019, I called Yonatan in Paris and asked that our reporter, Miri Krymolowski, who was supposed arrive Publisher: in Paris, interview him for our magazine. “Not about today’s “Rokdim-Nirkoda” – Rokdim in activities”, I said, “but rather about your place in the history association with the Israeli Dance and development of Israeli folk dance from the 1940s to the Ruth Goodman Institute Inc. (IDI), U.S.A., Robert beginning of the 21st century. Levine, President, Ted Comet, Chairman No doubt there is much to hear from him, I thought. Editors: Yonatan happily agreed and asked me to call him when he arrives Yaron Meishar, Ruth Goodman, in Israel at the beginning of January 2020, and we scheduled a Danny Uziel time to meet for an interview at the café that was next to his Editorial Staff – Nirkoda: house in Tel Aviv…The meeting did not take place…I received Danny Uziel Shani Karni Aduculesi, Judy Fixler, word that Yonatan was no longer with us. -

Freshman Year Reading Catalog 2017–2018

Simon & Schuster Freshman Year Reading Catalog 2017–2018 FreshmanYearReads.com Dear FYE Committee Member, We are delighted to present the 2017 – 2018 Freshman Year Reading catalog from Simon & Schuster. Simon & Schuster publishes a wide variety of fiction and nonfiction titles that align with the core purpose of college and university programs across the country—to support students in transition, promote engaging conversations, explore diverse perspectives, and foster community during the college experience. If you don’t see a title that fits your program’s needs, we are ready to work with you to find the perfect book for your campus or community program. Visit FreshmanYearReads.com for author videos, reading group guides, and to request review copies. For questions about discounts on large orders, or if you’re interested in having an author speak on campus, please email [email protected]. We’d love to hear from you! For a full roster of authors available for speaking engagements, visit the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at SimonSpeakers.com. You can also contact the Speakers Bureau directly by calling (866) 248-3049 or by emailing [email protected]. If the author you are interested in is not represented by the Speakers Bureau, please send us an email at [email protected]. Best, The Simon & Schuster Education & Library Group ORDERING INFO Simon & Schuster offers generous discounts on bulk purchases of books for FYE programs, one-reads, and educational use where the books are given away. The breakdown -

Peggy Dillner, President Education Resource Center, U of Delaware [email protected]

DLA Bulletin Newsletter of the Delaware Library Association Fall 2009 http://www2.lib.udel.edu/dla Protecting a person’s right to read has to be a President’s Letter primary commitment of every librarian as we serve Protecting Our Right to Read! as 1st amendment advocates. Have you read the Library Bill of Rights lately? It’s easily accessible at What do Wilkinson’s The ALA’s Office of Intellectual Freedom. Does your Complete Illustrated library have an updated, strong statement on Encyclopedia of the World’s selection and reconsideration of materials? What a Firearms, Chris Crutcher’s fine memorial tribute to Judith Krug, director of The Sledding Hill, Crutcher’s OIF since its founding in 1967, to review, update, Whale Talk, and all of Ellen and re-affirm your library’s obligation to providing Hopkins books (Crank, Glass, a forum for information and ideas for all. Burned, Impulse, Identical) have in common? All these books for youth have September 26 – October 3 is Banned Books Week. been challenged in a school or public library within Information and ideas can be found at http:// this past year. Thankfully, all also continue to be www.ala.org/ala/issuesadvocacy/banned/ available to young people in these schools and bannedbooksweek/index.cfm. libraries. What are you doing in your library to celebrate our You have likely all seen the list from ALA of the top right to read? ten challenged books this year (challenged in 2008). 1. And Tango Makes Three, PeggyDLA Dillner President by Justin Richardson and Peter Parnell 2. -

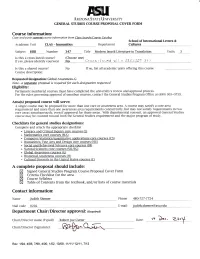

Dare: R O ).. , Z-O R

AnrzoxR Srnrn UN Ivr Rs ttv GENERAL STUDIES COURSE PROPOSAL COVER FORM Course information: Copl, qn4 paste current course infbrmation from Class Search/Course Cataloq. School of International Letters & Academic Unit CLAS - humanities Department *Q&fS! Subject -EE_E - -_ Number 347 Title ModernlsraeliLiteraturc-lUJfenstgtiq!-_ tlnits: *3 Is this a cross-listed course? (Choose one) If yes, please identify course(s) Nq Is this a shared course? No lf so, list all academic units offering this course Coursc dcscription: Requested,desigration: Global Awareness-G Note- a seoarate proposal is required for each designation requested Eligibility: Permanent numbered courses must have completed the university's review and approval process. For the rules governing approval of omnibus courses, contact the General Studies Program Office at (480) 965-0739. Area(s) proposed course will serve: A single course may be proposed for more than one core or arryareness area. A cotrrse may satisfy a core area requirement and more than one atvareness area requirements concurrently, but may not satisfy requirements in two core areas simultaneously, even if approved for th<lse areas. With departmental consent, an approved General Studies colrrse may be counted torvard both the General Studies requirement and the major program of study. Checklists for general studies designations: Complete and attach the appropriate checklist . Literaqy and Critical Inquiry core courses (L) . Mathematics core courses (MA) . Computer/statistics/quantitative applications core coulses