Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Avid Readers Club Grades 5 and 6 2018-2019 Round #1: Discussions Will Be in the Week of November 26

Avid Readers Club Grades 5 and 6 2018-2019 Round #1: Discussions will be in the week of November 26 Fiction Choice Men of Iron. Howard Pyle. One hundred years ago Howard Pyle wrote down the classic stories of King Arthur, Robin Hood and other legendary tales. His are considered to be of the most well-done versions of these tales. In this story, the youthful hero, Myles Falworth, is the son of a lord unjustly condemned for treason in the days of King Henry IV. How Myles grew as a knight is brought to life in this exciting story of chivalry and adventure! You may also read, Otto of the Silver Hand, also by Howard Pyle. Biography Choice Elizabeth Blackwell: A Doctor’s Triumph. Nancy Kline. The First Woman Doctor. Rachel Baker. Choose either one of these versions and read the inspiring story of the first woman doctor. It wasn’t easy for her in 1840 when she set out to become a doctor during a time when there were no women doctors in America. People laughed at her, played tricks on her, even threw things at her…but she pursued her dream! Classics from the Summer Reading List Little Women/Little Men – Louisa May Alcott The Princess and the Goblin, The Princess and Curdie - George MacDonald If you read one of these or still want to read them, let Mrs. D. know. These are “anytime” books. Discussions will happen anytime! I plan to read the following book(s) by the week of November 26: • Men of Iron or Otto of the Silver Hand. -

![Biographies of Women Scientists for Young Readers. PUB DATE [94] NOTE 33P](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6994/biographies-of-women-scientists-for-young-readers-pub-date-94-note-33p-1256994.webp)

Biographies of Women Scientists for Young Readers. PUB DATE [94] NOTE 33P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 368 548 SE 054 054 AUTHOR Bettis, Catherine; Smith, Walter S. TITLE Biographies of Women Scientists for Young Readers. PUB DATE [94] NOTE 33p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Biographies; Elementary Secondary Education; Engineering Education; *Females; Role Models; Science Careers; Science Education; *Scientists ABSTRACT The participation of women in the physical sciences and engineering woefully lags behind that of men. One significant vehicle by which students learn to identify with various adult roles is through the literature they read. This annotated bibliography lists and describes biographies on women scientists primarily focusing on publications after 1980. The sections include: (1) anthropology, (2) astronomy,(3) aviation/aerospace engineering, (4) biology, (5) chemistry/physics, (6) computer science,(7) ecology, (8) ethology, (9) geology, and (10) medicine. (PR) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** 00 BIOGRAPHIES OF WOMEN SCIENTISTS FOR YOUNG READERS 00 "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY Once of Educational Research and Improvement Catherine Bettis 14 EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION Walter S. Smith CENTER (ERIC) Olathe, Kansas, USD 233 M The; document has been reproduced aS received from the person or organization originating it 0 Minor changes have been made to improve Walter S. Smith reproduction quality University of Kansas TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES Points of view or opinions stated in this docu. INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)." ment do not necessarily rpresent official OE RI position or policy Since Title IX was legislated in 1972, enormous strides have been made in the participation of women in several science-related careers. -

Teaching About Women's Lives to Elementary School Children

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Women's Studies Quarterly Archives and Special Collections 1980 Teaching about Women's Lives to Elementary School Children Sandra Hughes How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/wsq/449 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Teaching about Women's Lives to Elementary School Children By Sandra Hughes As sixth-grade teachers with a desire to teach students about the particular surprised me, for they showed very little skepticism of historical role of women in the United States, my colleague and I a "What do we have to do this for?" nature. I found that there created a project for use in our classrooms which would was much opportunity for me to teach about the history of maximize exposure to women's history with a minimum of women in general, for each oral report would stimulate teacher effort. This approach was necessary because of the small discussion not only about the woman herself, but also about the amount of time we had available for gathering and organizing times in which she lived and the other factors that made her life material on the history of women and adapting it to the what it was. Each student seemed to take a particular pride in elementary level. the woman studied-it could be felt in the tone of their voices Since textbook material on women is practically when they began, "My woman is . -

Annual Report 2014

Annual Report 2014 “Service is the rent you pay for room on this “You cannot shake hands earth.” Board of Directorswith a clenched fist.” “Never doubt that a ‐Shirley Chisholm(as of 12/31/14) Indira Gandhi small group of thoughtful Jeseñia Brown, President Delaine Bailey-Lane, Vice President committed citizens can Christina Stoneburner, Esq., Treasurer change the world. Indeed, “How wonderfulDiane it Ruffle, is Secretary“No real social change that nobody needMelody Brownwait has ever been brought it is the only thing that Sabrina Elson ever has.” a single momentBarbara before Gaba, Ph.D. about without a Patricia Granda Margaret Mead starting to improveJaney Hamlett the revolution... revolution is world.” Jacqueline Jenkins but thought carried into Natalie Kraner, Esq. “The first problem for all Anne Frank Lois Nelson action.” Karen Pfeifer-Jones Emma Goldman of us, men and women, Phyllis Reich “If society willShruti notShah is not to learn, but to admit of woman’s “Prejudice is a burden unlearn.” The Mission of the YWCA USA ‐Gloria Steinem free development,The YWCA is dedicated to thateliminating confuses racism, empowering the past, women then societyand promotingmust be peace, justice,threatens freedom and dignitythe future for all. and “For what is done or remodeled.”The Local Purposerenders of the YWCA the present Union County Elizabeth BlackwellThe YWCA Union County seeksinaccessible.” to create an environment through which learnedwomen empower by one class of themselves and work to lead non-violent lives. The ultimate purpose is to heal the wounds of women and children, whether Mayathey are Angelouof the heart, mind, body, or soul. -

My Name Is Not Isabella a Common Core State Standards-Aligned Guide Grades K–2 By: Jennifer Fosberry

EDUCATOR'S GUIDE My Name Is Not Isabella A Common Core State Standards-aligned Guide Grades K–2 By: Jennifer Fosberry PreReading Questions & Activities Throughout this book, Isabella pretends she is different famous people from history. Ask students: “Have you ever pretended you were someone else? Why did you choose that person?” Do a picture book walk-through. Before you read the book to the class, have them closely examine the illustrations on each page. Discuss what is happening. Have students identify illustration details and explain what the details tell them about the story’s characters, settings, and events. Have students examine the cover of the book. Read the title. Discuss what they think the story will be about. Vocabulary In this book, students will encounter the following professions and historical fi gures. Using the biographical sketches provided by the book, acquaint the class with the following: Astronaut Sally Ride Sharpshooter Annie Oakley Activist Rosa Parks Scientist Marie Curie Doctor Elizabeth Blackwell Discussion Questions & Activities Readers Theater Now that students have read the book, performing it as a group is an effective way to improve comprehension. My Name Is Not Isabella is a perfect text for this activity because Isabella herself plays many different roles throughout the book. Identify the characters in the book and the personas Isabella assumes. NOTE: 1. If class size requires, use a different mother and Isabella for each scene. Alternatively, the instructor may play the mother in order to manage and prompt performers. 2. Transform the line “I am not Isabella...” to “She is not Isabella...” and have this line read by a chorus composed of class members not involved in the current scene. -

European Journal of American Studies, 10-1 | 2015 Introduction : Waging Health: Women in Nineteenth-Century American Wars 2

European journal of American studies 10-1 | 2015 Special Issue: Women in the USA Introduction : Waging Health: Women in Nineteenth-Century American Wars Carmen Birkle and Justine Tally Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/10665 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.10665 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Carmen Birkle and Justine Tally, “Introduction : Waging Health: Women in Nineteenth-Century American Wars”, European journal of American studies [Online], 10-1 | 2015, document 2.1, Online since 31 March 2015, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejas/10665 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.10665 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Creative Commons License Introduction : Waging Health: Women in Nineteenth-Century American Wars 1 Introduction : Waging Health: Women in Nineteenth-Century American Wars Carmen Birkle and Justine Tally 1 Thinking of war from a U.S.-American perspective will almost immediately evoke associations of male soldiers fighting heroic battles for a good cause such as democracy and/or the liberation of people from dictatorships, tyrannies, and torture. However, as more detailed and on-site news coverage has increasingly shown, this vision is entirely too limited. Among many possible revisionist perspectives is that of those women who have been involved in wars from a medical point of view and have significantly changed the life of soldiers through their work as doctors, nurses and care-givers. Among the more well-known, the British nurse Florence Nightingale revolutionized nursing and hygiene in the nineteenth century so that for the first time during the Crimean War there would not be more soldiers who died of diseases and infections rather than on the battlefield; and the Jamaican “doctress” and nurse, Mary Seacole, ran a hotel and became a mother figure for many soldiers during the same war. -

Elizabeth Blackwell: America's First Woman Doctor

Elizabeth Blackwell: LEVELED BOOK • T America’s First Woman Doctor Elizabeth A Reading A–Z Level T Leveled Book Blackwell: Word Count: 1,188 America’s First Woman Doctor Written by Sean McCollum Illustrated by Gabhor Utomo Visit www.readinga-z.com www.readinga-z.com for thousands of books and materials. Photo Credits: Page 3: courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York; page 7: © Flip Schulke/ Elizabeth Corbis; page 14: © Bettmann/Corbis Blackwell: Page 3: Elizabeth Blackwell as a young woman America’s First Woman Doctor Elizabeth Blackwell: America’s First Woman Doctor Level T Leveled Book Written by Sean McCollum © Learning A–Z Correlation Illustrated by Gabhor Utomo Written by Sean McCollum LEVEL T Illustrated by Gabhor Utomo Fountas & Pinnell P All rights reserved. Reading Recovery 38 DRA 38 www.readinga-z.com www.readinga-z.com Tough Enough The professor cut into the dead body while his medical students looked on. Some young men in the class blushed. Others looked sick or laughed nervously. Elizabeth Blackwell was determined Table of Contents not to show any emotion. She watched the demonstration closely while pinching her Tough Enough ......................... 4 hand as hard as she could. The pain helped A New Direction ........................ 5 her keep her face still. She had to show she was tough enough. Against the Odds ....................... 7 The year was 1847, and Elizabeth was the “This Is the Way to Learn!” .............. 10 first woman ever to attend medical college. Champion for Women Doctors .......... 12 Most people at the time thought women were too weak and delicate to handle the blood and Thank You, Dr. -

Women's History Month

DiversityInc Women’s History Month MEETING IN A BOX For ALL employees 1. HISTORIC TIMELINE e recommend you start your Discussion Questions for Employees employees’ cultural-competence Wlesson on the increasing value of having women in leadership What have been the most Why are “firsts” important to note? ??? significant changes in women’s ??? What other barrier breakers have positions by using this historic timeline. roles in the past 50 years? In you witnessed in your lifetime? It’s important to note how women’s the past 10 years? roles have evolved, how flexible work This is a personal discussion Ask the employees why they designed to help the employee note arrangements allow more women think there has been so much other barrier breakers historically to combine family and professional rapid change and, most (cite Elizabeth Blackwell, Muriel responsibilities, and how many glass importantly, if it’s enough. Have Siebert and female CEOs, available ceilings still have not been shattered. women talk about their own at www.DiversityInc.com/fortune- The timeline shown here illustrates experiences and men talk about 500-ceos). This discussion can be significant dates in women’s history and the experiences of their wives, further explored after the facts & major historic figures. daughters, sisters and friends. figures section below is discussed. 2. FACTS & FIGURES fter discussion of the timeline, the Discussion Questions for Employees next step is to review available Adata and understand areas in Why has it been so difficult to get girls and women into STEM (Science, Technology, which women have made significant ??? progress in the United States but major Engineering and Mathematics) positions and what should schools and companies do to change that? opportunities remain. -

Searching for Terms

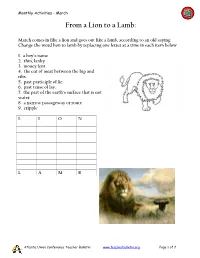

Monthly Activities - March From a Lion to a Lamb: March comes in like a lion and goes out like a lamb, according to an old saying. Change the word lion to lamb by replacing one letter at a time in each item below 1. a boy’s name 2. thin, lanky 3. money lent 4. the cut of meat between the hip and ribs. 5. past participle of lie. 6. past tense of lay. 7. the part of the earth’s surface that is not water 8. a narrow passageway or route 9. cripple L I O N L A M B Atlantic Union Conference Teacher Bulletin www.teacherbulletin.org Page 1 of 7 Monthly Activities - March KEY From a Lion to a Lamb: L I O N L E O N L E A N L O A N L O I N L A I N L A I D L A N D L A N E L A M E L A M B Atlantic Union Conference Teacher Bulletin www.teacherbulletin.org Page 2 of 7 Monthly Activities - March Women Who Changed History A List of Women Achievers March is Women’s History Month. This list of notable women and links is adapted from Scholastic’s website. Louisa May Alcott: 1832–1888 Author who produced the first literature for the mass market of juvenile girls in the 19th century. Her most popular, Little Women, was just one of 270 works that she published. http://www.greatwomen.org/women.php?action=viewone&id=8 Susan B. Anthony: 1820–1906 The 19th century women’s movement’s most powerful organizer. -

Babe Didrikson Zaharias Super-Athlete

2 MORE THAN 150 YEARS OF WOMEN’S HISTORY March is Women’s History Month. The Women’s Rights Movement started in Seneca Falls, New York, with the first Women’s Rights Convention in 1848.Out of the convention came a declaration modeled upon the Declaration of Independence, written by a woman named Elizabeth Cady THE WOMEN WE HONOR Stanton. They worked inside and outside of their homes. business and labor; science and medicine; sports and It demanded that women be given They pressed for social changes in civil rights, the peace exploration; and arts and entertainment. all the rights and privileges that belong movement and other important causes. As volunteers, As you read our mini-biographies of these women, they did important charity work in their communities you’ll be asked to think about what drove them toward to them as citizens of the United States. and worked in places like libraries and museums. their achievements. And to think how women are Of course, it was many years before Women of every race, class and ethnic background driven to achieve today. And to consider how women earned all the rights the have made important contributions to our nation women will achieve in the future. Seneca Falls convention demanded. throughout its history. But sometimes their contribution Because women’s history is a living story, our list of has been overlooked or underappreciated or forgotten. American women includes women who lived “then” American women were not given Since 1987, our nation has been remembering and women who are living—and achieving—”now.” the right to vote until 1920. -

Women's History Month

DiversityInc MEETING IN A BOX Women’s History Month For All Employees or Women’s History Month, we F are supplying a historic Timeline of women’s achievements, Facts & Figures demonstrating women’s advancement (and opportunities) in education and business, and our cultural-competence series “Things NOT to Say,” focusing on women at work. This information should be distributed to your entire workforce and also should be used by your women’s resource group both internally and externally as a year-round educational tool. PAGE 1 DiversityInc For All Employees MEETING IN A BOX Women’s History Month 1 HISTORIC TIMELINE We recommend you start your employees’ cultural-competence lesson on the increasing value of having women in leadership positions by using this historic Timeline. It’s important to note how women’s roles have evolved, how flexible work arrangements allow more women to combine family and professional responsibilities, and how many glass ceilings still have not been shattered. The Timeline shown here illustrates significant dates in women’s history and major historic figures. ? ? ? Discussion Questions for Employees What have been the most significant changes in women’s roles in the past 50 years? In the past 10 years? Ask the employees why they think there has been so much rapid change and, most importantly, if it’s enough. Have women talk about their own experiences and men talk about the experiences of their wives, daughters, sisters and friends. Why are “firsts” important to note? What other barrier breakers have you witnessed in your lifetime? This is a personal discussion designed to help the employee note other barrier breakers historically. -

American Medical Women's Association 2021 AWARDS

American Medical Women’s Association 2021 AWARDS Presidential Award – Uché Blackstock, MD Dr. Uché Blackstock is a thought leader and sought-after speaker on bias and racism in health care. She is the Founder and CEO of Advancing Health Equity, which partners with healthcare and related organizations to address racism in healthcare and to eradicate racial health inequities. In 2019, Dr. Blackstock was recognized by Forbes magazine as one of “10 Diversity and Inclusion Trailblazers You Need to Get Familiar With.” In 2020, she was one of thirty-one inaugural leaders awarded an unrestricted grant for her advocacy work from the Black Voices for Black Justice Fund. Dr. Blackstock’s writing has been featured in national news outlets, and she is a regular contributor to Yahoo News and cable and broadcast news to discuss the Coronavirus pandemic and amplify the message around racial health inequities. Dr. Blackstock is a former Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine and the former Faculty Director for Recruitment, Retention and Inclusion in the Office of Diversity Affairs at NYU School of Medicine. Dr. Blackstock received both her undergraduate and medical degrees from Harvard University. She currently lives in Brooklyn, New York with her two small children. Presidential Award – Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (posthumous) Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Associate Justice, was born in Brooklyn, NY, March 15, 1933. She married Martin D. Ginsburg in 1954, and had a daughter, Jane, and a son, James. She received her B.A. from Cornell University, attended Harvard Law School, and received her LL.B. from Columbia Law School. She served as a law clerk to the Honorable Edmund L.