An Analysis of Selected Speeches by Anwar El-Sadat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

King Faisal Assassinated

o.i> (Ejmttrrttrut iatlg (Sampita Serving Storrs Since 1896 VOL. LXXVIII NO. 102 STORRS, CONNECTICUT WEDNESDAY. MARCH 26. 1975 5 CENTS OFF CAMPUS King Faisal assassinated BEIRUT- (UPI) Saudi Khalid underwent heart surgery sacred cities of Mecca and monarch was wounded and Washington said the 31-year-old Arabi's King Faisal, spiritual in Cleveland, Ohio, three years Medina. hospitalized. Then. a .issassin was son of King Faisal's leader of the world's 600 million ago. t c a r - c h o k c d .innounccr half brother. Prince Musaid. The nephew walked the Moslems and master of the Faisal was killed while holding broadcast the news that Faisal Mideast's largest oil fields, was court in his Palace to mark the length of the hall apparently had died. Immediately all radio They said in 1966 he studied assassinated Tuesday as he sat on mniversary of the birth of intended to greet the seated King stations switched to readings of English at San Francisco State a golden chair in the mirrored Prophet Mohammed the with the customary kiss on both the Koran and thousands of College, and the following year hall of his palace by a deranged founder of the Islamic religion checks. Instead, he pulled a Saudis. (Tying and spreading he enrolled in a course in member of his own family. whose 600 million followers revolver from beneath his their arms in Uriel, surged into mechanical engineering at the Faisal, 68, died of wounds revered Faisal as their spiritual flowing robe and fired. the streets of Riyadh. -

Literary Networks and the Making of Egypt's Nineties Generation By

Writing in Cairo: Literary Networks and the Making of Egypt’s Nineties Generation by Nancy Spleth Linthicum A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Near Eastern Studies) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Carol Bardenstein, Chair Associate Professor Samer Ali Professor Anton Shammas Associate Professor Megan Sweeney Nancy Spleth Linthicum [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-9782-0133 © Nancy Spleth Linthicum 2019 Dedication Writing in Cairo is dedicated to my parents, Dorothy and Tom Linthicum, with much love and gratitude for their unwavering encouragement and support. ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my committee for their invaluable advice and insights and for sticking with me throughout the circuitous journey that resulted in this dissertation. It would not have been possible without my chair, Carol Bardenstein, who helped shape the project from its inception. I am particularly grateful for her guidance and encouragement to pursue ideas that others may have found too far afield for a “literature” dissertation, while making sure I did not lose sight of the texts themselves. Anton Shammas, throughout my graduate career, pushed me to new ways of thinking that I could not have reached on my own. Coming from outside the field of Arabic literature, Megan Sweeney provided incisive feedback that ensured I spoke to a broader audience and helped me better frame and articulate my arguments. Samer Ali’s ongoing support and feedback, even before coming to the University of Michigan (UM), likewise was instrumental in bringing this dissertation to fruition. -

Saudi Arabia Under King Faisal

SAUDI ARABIA UNDER KING FAISAL ABSTRACT || T^EsIs SubiviiTTEd FOR TIIE DEqREE of ' * ISLAMIC STUDIES ' ^ O^ilal Ahmad OZuttp UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. ABDUL ALI READER DEPARTMENT OF ISLAMIC STUDIES ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1997 /•, •^iX ,:Q. ABSTRACT It is a well-known fact of history that ever since the assassination of capital Uthman in 656 A.D. the Political importance of Central Arabia, the cradle of Islam , including its two holiest cities Mecca and Medina, paled into in insignificance. The fourth Rashidi Calif 'Ali bin Abi Talib had already left Medina and made Kufa in Iraq his new capital not only because it was the main base of his power, but also because the weight of the far-flung expanding Islamic Empire had shifted its centre of gravity to the north. From that time onwards even Mecca and Medina came into the news only once annually on the occasion of the Haj. It was for similar reasons that the 'Umayyads 661-750 A.D. ruled form Damascus in Syria, while the Abbasids (750- 1258 A.D ) made Baghdad in Iraq their capital. However , after a long gap of inertia, Central Arabia again came into the limelight of the Muslim world with the rise of the Wahhabi movement launched jointly by the religious reformer Muhammad ibn Abd al Wahhab and his ally Muhammad bin saud, a chieftain of the town of Dar'iyah situated between *Uyayana and Riyadh in the fertile Wadi Hanifa. There can be no denying the fact that the early rulers of the Saudi family succeeded in bringing about political stability in strife-torn Central Arabia by fusing together the numerous war-like Bedouin tribes and the settled communities into a political entity under the banner of standard, Unitarian Islam as revived and preached by Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. -

Televised Ceremonies of Reconciliation

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (ASC) Annenberg School for Communication 1996 Staging Peace: Televised Ceremonies of Reconciliation Tamar Liebes The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Elihu Katz University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Liebes, T., & Katz, E. (1996). Staging Peace: Televised Ceremonies of Reconciliation. The Communication Review, 2 (2), 235-257. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714429709368558 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/262 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Staging Peace: Televised Ceremonies of Reconciliation Abstract The visit of Egypt's President Anwar Sadat to Jerusalem was the model for Dayan and Katz's conceptualization of the genre of media events, as live programs which have the power to transform history. Fifteen years later, a series of televised reconciliation ceremonies, which marked the stages of the peace process between Israel and its Arab neighbors (the Palestinians and the Jordanians), are used to re-examine the model. We demonstrate (1) how the effectiveness of these ceremonies depends on the type of contract among the three participants-leaders, broadcasters and public-each of whom displays different kinds of reservations, and (2) how the aura of the ceremonies draws on the prior status of the participants (Hussein), but also confers status (Arafat). Disciplines Communication | Social and Behavioral Sciences This journal article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/262 Staging Peace: Televised Ceremonies of Reconciliation Tamar Liebes and Elihu Katz The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem 91905 ISRAEL The visit of Egypt's President Anwar Sadat to Jerusalem was the model for Dayan and Katz's conceptualization of the genre of media events, as live programs which have the power to transform history. -

Us Military Assistance to Saudi Arabia, 1942-1964

DANCE OF SWORDS: U.S. MILITARY ASSISTANCE TO SAUDI ARABIA, 1942-1964 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Bruce R. Nardulli, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2002 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Allan R. Millett, Adviser Professor Peter L. Hahn _______________________ Adviser Professor David Stebenne History Graduate Program UMI Number: 3081949 ________________________________________________________ UMI Microform 3081949 Copyright 2003 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ____________________________________________________________ ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road PO Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 ABSTRACT The United States and Saudi Arabia have a long and complex history of security relations. These relations evolved under conditions in which both countries understood and valued the need for cooperation, but also were aware of its limits and the dangers of too close a partnership. U.S. security dealings with Saudi Arabia are an extreme, perhaps unique, case of how security ties unfolded under conditions in which sensitivities to those ties were always a central —oftentimes dominating—consideration. This was especially true in the most delicate area of military assistance. Distinct patterns of behavior by the two countries emerged as a result, patterns that continue to this day. This dissertation examines the first twenty years of the U.S.-Saudi military assistance relationship. It seeks to identify the principal factors responsible for how and why the military assistance process evolved as it did, focusing on the objectives and constraints of both U.S. -

Download Chapter (PDF)

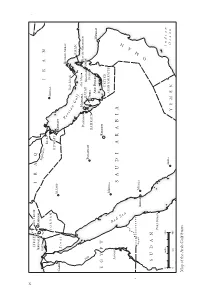

x ISRAEL WEST BANK IRAQ Jerusalem Amman Eup GAZA hrates IRAN Basra JORDAN Shiraz KUWAIT Al Jauf Kuwait Cairo Sinai P e Bandar Abbas r s i a Tunb Islands n G u OMAN l f Abu Musa Dammam Manama Ras Al-Khaimah N QATAR Ajman il Sharjah e Buraydah Dubai BAHRAIN Doha Abu Dhabi Muscat EGYPT Riyadh UNITED Medina ARAB EMIRATES R e Aswan d SAUDI ARABIA S e a N A Jeddah Mecca M O SUDAN Port Sudan 0 miles 250 Indian Abha Ocean 0 km 400 YEMEN Map of the Arab Gulf States 1. Muslim pilgrims circumambulate (tawaf ) the sacred Kaaba during sunrise after fajr prayer in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. 2. President Nixon and Mrs Nixon welcome King Faisal of Saudi Arabia on a visit to the United States in May 1971. 3. Henry Kissinger (left), the US Secretary of State, meets the Shah of Iran (right) in Zurich in early 1975. 4. Sheik Yamani talks about oil and the Palestinian problem during a press conference in Saudi Arabia in July 1979. 5. Crowds of Iranian protestors demonstrate in support of exiled Ayatollah Sayyid Ruhollah Khomeini in 1978, the year prior to the revolution. 6. Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein addresses members of his armed forces shortly before the invasion of Iran in September 1980. 7. Saudi Arabian soldiers prepare to load into armoured personnel carriers during clean-up operations following the Battle of Khafji, 2 February 1991. The Battle of Khafji was the first major ground engagement of the 1991 Gulf war. 8. Palestinian women demonstrate with Palestinian and Iraqi flags and portraits of Yasser Arafat and Saddam Hussein in the West Bank during the Kuwait crisis of 1990–91. -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

The COVID-19 Crisis: Impact and Implications

The COVID-19 Crisis: Impact and Implications Editor: Efraim Karsh Mideast Security and Policy Studies No. 176 THE BEGIN-SADAT CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES BAR-ILAN UNIVERSITY Mideast Security and Policy Studies No. 176 The COVID-19 Crisis: Impact and Implications Editor: Efraim Karsh The COVID-19 Crisis: Impact and Implications Editor: Efraim Karsh © The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies Bar-Ilan University Ramat Gan 5290002 Israel Tel. 972-3-5318959 Fax. 972-3-5359195 [email protected] www.besacenter.org ISSN 0793-1042 July 2020 Cover image: Coronavirus image via Pixabay The Begin-Sadat (BESA) Center for Strategic Studies The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies is an independent, non-partisan think tank conducting policy-relevant research on Middle Eastern and global strategic affairs, particularly as they relate to the national security and foreign policy of Israel and regional peace and stability. It is named in memory of Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat, whose efforts in pursuing peace laid the cornerstone for conflict resolution in the Middle East. Mideast Security and Policy Studies serve as a forum for publication or re-publication of research conducted by BESA associates. Publication of a work by BESA signifies that it is deemed worthy of public consideration but does not imply endorsement of the author’s views or conclusions. Colloquia on Strategy and Diplomacy summarize the papers delivered at conferences and seminars held by the Center for the academic, military, official and general publics. In sponsoring these discussions, the BESA Center aims to stimulate public debate on, and consideration of, contending approaches to problems of peace and war in the Middle East. -

Rivalry in the Middle East: the History of Saudi-Iranian Relations and Its Implications on American Foreign Policy

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Summer 2017 Rivalry in the Middle East: The History of Saudi-Iranian Relations and its Implications on American Foreign Policy Derika Weddington Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons, International Relations Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Weddington, Derika, "Rivalry in the Middle East: The History of Saudi-Iranian Relations and its Implications on American Foreign Policy" (2017). MSU Graduate Theses. 3129. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3129 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RIVALRY IN THE MIDDLE EAST: THE HISTORY OF SAUDI-IRANIAN RELATIONS AND ITS IMPLICATIONS ON AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science, Defense and Strategic Studies By Derika Weddington August 2017 RIVALARY IN THE MIDDLE EAST: THE HISTORY OF SAUDI-IRANIAN RELATIONS AND ITS IMPLICATIONS ON AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY Defense and Strategic Studies Missouri State University, August 2017 Master of Science Derika Weddington ABSTRACT The history of Saudi-Iranian relations has been fraught. -

INSTITUTION Congress of the US, Washington, DC. House Committee

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 303 136 IR 013 589 TITLE Commercialization of Children's Television. Hearings on H.R. 3288, H.R. 3966, and H.R. 4125: Bills To Require the FCC To Reinstate Restrictions on Advertising during Children's Television, To Enforce the Obligation of Broadcasters To Meet the Educational Needs of the Child Audience, and for Other Purposes, before the Subcommittee on Telecommunications and Finance of the Committee on Energy and Commerce, House of Representatives, One Hundredth Congress (September 15, 1987 and March 17, 1988). INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, DC. House Committee on Energy and Commerce. PUB DATE 88 NOTE 354p.; Serial No. 100-93. Portions contain small print. AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402. PUB TYPE Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Materials (090) -- Viewpoints (120) -- Reports - Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Advertising; *Childrens Television; *Commercial Television; *Federal Legislation; Hearings; Policy Formation; *Programing (Broadcast); *Television Commercials; Television Research; Toys IDENTIFIERS Congress 100th; Federal Communications Commission ABSTRACT This report provides transcripts of two hearings held 6 months apart before a subcommittee of the House of Representatives on three bills which would require the Federal Communications Commission to reinstate restrictions on advertising on children's television programs. The texts of the bills under consideration, H.R. 3288, H.R. 3966, and H.R. 4125 are also provided. Testimony and statements were presented by:(1) Representative Terry L. Bruce of Illinois; (2) Peggy Charren, Action for Children's Television; (3) Robert Chase, National Education Association; (4) John Claster, Claster Television; (5) William Dietz, Tufts New England Medical Center; (6) Wallace Jorgenson, National Association of Broadcasters; (7) Dale L. -

Forgotten in the Diaspora: the Palestinian Refugees in Egypt

Forgotten in the Diaspora: The Palestinian Refugees in Egypt, 1948-2011 Lubna Ahmady Abdel Aziz Yassin Middle East Studies Center (MEST) Spring, 2013 Thesis Advisor: Dr. Sherene Seikaly Thesis First Reader: Dr. Pascale Ghazaleh Thesis Second Reader: Dr. Hani Sayed 1 Table of Contents I. CHAPTER ONE: PART ONE: INTRODUCTION……………………………………………...…….4 A. PART TWO: THE RISE OF THE PALESTINIAN REFUGEE PROBLEM…………………………………………………………………………………..……………..13 B. AL-NAKBA BETWEEN MYTH AND REALITY…………………………………………………14 C. EGYPTIAN OFFICIAL RESPONSE TO THE PALESTINE CAUSE DURING THE MONARCHAL ERA………………………………………………………………………………………25 D. PALESTINE IN THE EGYPTIAN PRESS DURING THE INTERWAR PERIOD………………………………………………………………………………………………..…….38 E. THE PALESTINIAN REFUGEES IN EGYPT, 1948-1952………………………….……….41 II. CHAPTER TWO: THE NASSER ERA, 1954-1970 A. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND…………………………………………………………………….…45 B. THE EGYPTIAN-PALESTINIAN RELATIONS, 1954-1970……………..………………..49 C. PALESTINIANS AND THE NASEERIST PRESS………………………………………………..71 D. PALESTINIAN SOCIAL ORGANIZATIONS………………………………………………..…..77 E. LEGAL STATUS OF PALESTINIAN REFUGEES IN EGYPT………………………….…...81 III. CHAPTER THREE: THE SADAT ERA, 1970-1981 A. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND……………………………………………………………………….95 B. EGYPTIAN-PALESTINIAN RELATIONS DURING THE SADAT ERA…………………102 C. THE PRESS DURING THE SADAT ERA…………………………………………….……………108 D. PALESTINE IN THE EGYPTIAN PRESS DURING THE SADAT ERA……………….…122 E. THE LEGAL STATUS OF PALESTINIAN REFUGEES DURING THE SADAT ERA……………………………………………………………………………………………………….…129 IV. CHAPTER FOUR: -

Camp David's Shadow

Camp David’s Shadow: The United States, Israel, and the Palestinian Question, 1977-1993 Seth Anziska Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Seth Anziska All rights reserved ABSTRACT Camp David’s Shadow: The United States, Israel, and the Palestinian Question, 1977-1993 Seth Anziska This dissertation examines the emergence of the 1978 Camp David Accords and the consequences for Israel, the Palestinians, and the wider Middle East. Utilizing archival sources and oral history interviews from across Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, the United States, and the United Kingdom, Camp David’s Shadow recasts the early history of the peace process. It explains how a comprehensive settlement to the Arab-Israeli conflict with provisions for a resolution of the Palestinian question gave way to the facilitation of bilateral peace between Egypt and Israel. As recently declassified sources reveal, the completion of the Camp David Accords—via intensive American efforts— actually enabled Israeli expansion across the Green Line, undermining the possibility of Palestinian sovereignty in the occupied territories. By examining how both the concept and diplomatic practice of autonomy were utilized to address the Palestinian question, and the implications of the subsequent Israeli and U.S. military intervention in Lebanon, the dissertation explains how and why the Camp David process and its aftermath adversely shaped the prospects of a negotiated settlement between Israelis and Palestinians in the 1990s. In linking the developments of the late 1970s and 1980s with the Madrid Conference and Oslo Accords in the decade that followed, the dissertation charts the role played by American, Middle Eastern, international, and domestic actors in curtailing the possibility of Palestinian self-determination.