Uncovering San Francisco Muni's Proof-Of-Payment Patterns to Help

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Deloitte City Mobility Index Gauging Global Readiness for the Future of Mobility

The Deloitte City Mobility Index Gauging global readiness for the future of mobility By: Simon Dixon, Haris Irshad, Derek M. Pankratz, and Justine Bornstein the Internet of Things, artificial intelligence, and Where should cities other digital technologies to develop and inform go tomorrow? intelligent decisions about people, places, and prod- ucts. A smart city is a data-driven city, one in which Unfortunately, when it comes to designing and municipal leaders have an increasingly sophisti- implementing a long-term vision for future mobil- cated understanding of conditions in the areas they ity, it is all too easy to ignore, misinterpret, or skew oversee, including the urban transportation system. this data to fit a preexisting narrative.1 We have seen In the past, regulators used questionnaires and sur- this play out in dozens of conversations with trans- veys to map user needs. Today, platform operators portation leaders all over the world. To build that can rely on databases to provide a more accurate vision, leaders need to gather the right data, ask the picture in a much shorter time frame at a lower cost. right questions, and focus on where cities should Now, leaders can leverage a vast array of data from go tomorrow. The Deloitte City Mobility Index Given the essential enabling role transportation theme analyses how deliberate and forward- plays in a city’s sustained economic prosperity,2 we thinking a city’s leaders are regarding its future set out to create a new and better way for city of- mobility needs. ficials to gauge the health of their mobility network 3. -

2017-2026 Samtrans Short Range Transit Plan

SAN MATEO COUNTY TRANSIT DISTRICT Short-Range Transit Plan Fiscal Years 2017 – 2026 May 3, 2017 Acknowledgements San Mateo County Transit District Board of Directors 2017 Rose Guilbault, Chair Charles Stone, Vice Chair Jeff Gee Carole Groom Zoe Kersteen-Tucker Karyl Matsumoto Dave Pine Josh Powell Peter Ratto Senior Staff Michelle Bouchard, Chief Operating Officer, Rail Michael Burns, Interim Chief Officer, Caltrain Planning / CalMod April Chan, Chief Officer, Planning, Grants, and Transportation Authority Jim Hartnett, General Manager/CEO Kathleen Kelly, Interim Chief Financial Officer / Treasurer Martha Martinez, Executive Officer, District Secretary, Executive Administration Seamus Murphy, Chief Communications Officer David Olmeda, Chief Operating Officer, Bus Mark Simon, Chief of Staff Short Range Transit Plan Project Staff and Contributors Douglas Kim, Director, Planning Lindsey Kiner, Senior Planner, Planning David Pape, Planner, Planning Margo Ross, Director of Transportation, Bus Transportation Karambir Cheema, Deputy Director ITS, Bus Transportation Ana Rivas, South Base Superintendent, Bus Transportation Ladi Millard, Director of Budgets, Finance Ryan Hinchman, Manager Financial Planning & Analysis, Finance Donald G. Esse, Senior Operations Financial Analyst, Bus Operations Leslie Fong, Senior Administrative Analyst, Grants Tina Dubost, Manager, Accessible Transit Services Natalie Chi, Bus Maintenance Contract Administrator, Bus Transportation Joan Cassman, Legal Counsel (Hanson Bridgett) Shayna M. van Hoften, Legal Counsel (Hanson -

California State Rail Plan 2005-06 to 2015-16

California State Rail Plan 2005-06 to 2015-16 December 2005 California Department of Transportation ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER, Governor SUNNE WRIGHT McPEAK, Secretary Business, Transportation and Housing Agency WILL KEMPTON, Director California Department of Transportation JOSEPH TAVAGLIONE, Chair STATE OF CALIFORNIA ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER JEREMIAH F. HALLISEY, Vice Chair GOVERNOR BOB BALGENORTH MARIAN BERGESON JOHN CHALKER JAMES C. GHIELMETTI ALLEN M. LAWRENCE R. K. LINDSEY ESTEBAN E. TORRES SENATOR TOM TORLAKSON, Ex Officio ASSEMBLYMEMBER JENNY OROPEZA, Ex Officio JOHN BARNA, Executive Director CALIFORNIA TRANSPORTATION COMMISSION 1120 N STREET, MS-52 P. 0 . BOX 942873 SACRAMENTO, 94273-0001 FAX(916)653-2134 (916) 654-4245 http://www.catc.ca.gov December 29, 2005 Honorable Alan Lowenthal, Chairman Senate Transportation and Housing Committee State Capitol, Room 2209 Sacramento, CA 95814 Honorable Jenny Oropeza, Chair Assembly Transportation Committee 1020 N Street, Room 112 Sacramento, CA 95814 Dear: Senator Lowenthal Assembly Member Oropeza: On behalf of the California Transportation Commission, I am transmitting to the Legislature the 10-year California State Rail Plan for FY 2005-06 through FY 2015-16 by the Department of Transportation (Caltrans) with the Commission's resolution (#G-05-11) giving advice and consent, as required by Section 14036 of the Government Code. The ten-year plan provides Caltrans' vision for intercity rail service. Caltrans'l0-year plan goals are to provide intercity rail as an alternative mode of transportation, promote congestion relief, improve air quality, better fuel efficiency, and improved land use practices. This year's Plan includes: standards for meeting those goals; sets priorities for increased revenues, increased capacity, reduced running times; and cost effectiveness. -

Caltrain Fare Study Draft Research and Peer Comparison Report

Caltrain Fare Study Draft Research and Peer Comparison Report Public Review Draft October 2017 Caltrain Fare Study Draft Research and Peer Comparison October 2017 Research and Peer Review Research and Peer Review .................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 2 A Note on TCRP Sources ........................................................................................................................................... 2 Elasticity of Demand for Commuter Rail ............................................................................... 3 Definition ........................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Commuter Rail Elasticity ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Comparison with Peer Systems ............................................................................................ 4 Fares ................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Employer Programs .................................................................................................................................................. -

Alameda Countywide Transportation Model

ALAMEDA COUNTY TRANSPORTATION COMMISSION ALAMEDA COUNTYWIDE TRANSPORTATION MODEL PLAN BAY AREA 2040 UPDATE Draft Documentation Report January, 2019 Alameda Countywide Travel Model Project #: 19752 January 10, 2019 Page i TABLE OF CONTENTS Alameda Countywide Transportation Model .......................................................................... i Plan Bay Area 2040 Update.................................................................................................................................. i Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................... i List of Tables ............................................................................................................................. iii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................. v Summary ................................................................................................................................. vii Key Features ......................................................................................................................................................... vii Key Updates .......................................................................................................................................................... ix Selected Consistency Results ............................................................................................................................ -

AQ Conformity Amended PBA 2040 Supplemental Report Mar.2018

TRANSPORTATION-AIR QUALITY CONFORMITY ANALYSIS FINAL SUPPLEMENTAL REPORT Metropolitan Transportation Commission Association of Bay Area Governments MARCH 2018 Metropolitan Transportation Commission Jake Mackenzie, Chair Dorene M. Giacopini Julie Pierce Sonoma County and Cities U.S. Department of Transportation Association of Bay Area Governments Scott Haggerty, Vice Chair Federal D. Glover Alameda County Contra Costa County Bijan Sartipi California State Alicia C. Aguirre Anne W. Halsted Transportation Agency Cities of San Mateo County San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission Libby Schaaf Tom Azumbrado Oakland Mayor’s Appointee U.S. Department of Housing Nick Josefowitz and Urban Development San Francisco Mayor’s Appointee Warren Slocum San Mateo County Jeannie Bruins Jane Kim Cities of Santa Clara County City and County of San Francisco James P. Spering Solano County and Cities Damon Connolly Sam Liccardo Marin County and Cities San Jose Mayor’s Appointee Amy R. Worth Cities of Contra Costa County Dave Cortese Alfredo Pedroza Santa Clara County Napa County and Cities Carol Dutra-Vernaci Cities of Alameda County Association of Bay Area Governments Supervisor David Rabbit Supervisor David Cortese Councilmember Pradeep Gupta ABAG President Santa Clara City of South San Francisco / County of Sonoma San Mateo Supervisor Erin Hannigan Mayor Greg Scharff Solano Mayor Liz Gibbons ABAG Vice President City of Campbell / Santa Clara City of Palo Alto Representatives From Mayor Len Augustine Cities in Each County City of Vacaville -

Transbay Transit Center

Transbay Transit Center TRANSBAY JOINT POWERS AUTHORITY FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS Transbay Transit Center Why do we need the Transbay Transit Center? It is time for public infrastructure to meet the needs of the 21st century. The project will centralize a fractured regional transportation network—making transit connections be- tween all points in the Bay Area fast and convenient. The new Transit Center will make public transit a convenient option as it is in other world-class cities, allowing people to travel and commute without the need for a car, thereby decreasing congestion and pollution. The Transit Center will provide a downtown hub in the heart of a new transit- friendly neighborhood with new homes, parks and shops, providing access to public transit literally at the foot of people’s doors. When will I be able to use the Transit Center? The Transit Center building will be completed in 2017 and will be a bustling transit and retail center for those who live, work and visit the heart of downtown San Francisco. When will I be able to take Caltrain into the new Transit Center? The construction of the underground rail extension for the Caltrain rail line and future High Speed Rail is planned to begin in 2012. It is estimated to be completed and operational, along with the Transit Center’s underground rail station, in 2018 or sooner if funding becomes What is the Transbay Transit available. Center Project? How many people will use it? When the rail component is complete, it is estimated that The Transbay Transit Center Project is a visionary more than 20 million people will use the Transit Center transportation and housing project that will transform annually. -

A Meeting of the New York City Transit Riders Council

A meeting of the New York City Transit Riders Council (NYCTRC) was convened at 12:00 pm on Thursday, January 29, 2020 in the 20th floor Board Room at 2 Broadway, New York, NY 10004. Member Attendance Andrew Albert (Chair) Present Burton M. Strauss Jr. (Vice Chair) Present Stuart Goldstein Present Christopher Greif Present William K. Guild Absent Marisol Halpern Present Sharon King Hoge Absent Trudy L. Mason Present Scott R. Nicholls Present Edith Prentiss Present Staff Attendance Lisa Daglian (Executive Director) Present Ellyn Shannon (Associate Director) Present Bradley Brashears (Planning Manager) Present Sheila Binesh (Transportation Planner) Present Deborah Morrison (Administrative Assistant) Present Non-member Attendance Name Affiliation Andy Byford NYCT Alex Elegudin NYCT Deborah Hall-Moore NYCT Rachel Cohen NYCT Debra Greif BFSSAC Ann Mannino BFSSAC Andrew Kurzweil RUN Jasmine Melzer Good Neighbors of Park Slope Joyce Jed Good Neighbors of Park Slope William Stanford, Jr. Concerned citizen Yvonne Morrow Concerned citizen Approval of Agenda for February 27, 2020 meeting. Approval of Minutes for January 29, 2020 meeting. Chair’s Report attached. Board Report Discussion Points: (To view full discussion visit PCAC Youtube Channel) • Andy Byford and Pete Tomlin resign from MTA-NYC Transit effective February 21st. • CBTC is moving along on Queens Boulevard, eventually on 8th Ave., etc… • Group Station Manger program – under Andy has improved station conditions. • Accessibility – next group of stations you will hear about from our presenter today. • Livonia – Junius stations will become connected and made accessible. • Subway ridership and OTP (84%) increases resulting from the Save Safe Seconds program. • Penn Station Master Plan - eight additional tracks – no decision has been made on repairs of the Hudson River tunnels. -

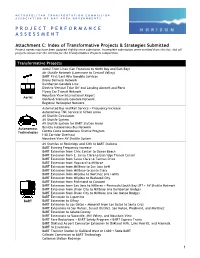

Attachment C: Index of Transformative Projects & Strategies Submitted Project Names May Have Been Updated Slightly Since Submission

METROPOLITAN TRANSPORTATION COMMISSION ASSOCIATION OF BAY AREA GOVERNMENTS PROJECT PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT Attachment C: Index of Transformative Projects & Strategies Submitted Project names may have been updated slightly since submission. Incomplete submissions were omitted from this list. Not all projects shown met the criteria for the Transformative Projects competition. Transformative Projects Aerial Tram Lines (San Francisco to North Bay and East Bay) Air Shuttle Network (Livermore to Central Valley) BART First/Last Mile Gondola Services Drone Delivery Network Dumbarton Gondola Line Electric Vertical Take Off and Landing Aircraft and Ports Flying Car Transit Network Mountain View International Airport Aerial Oakland/Alameda Gondola Network Regional Helicopter Network Automated Bus and Rail Service + Frequency Increase Autonomous TNC Service in Urban Areas AV Shuttle Circulators AV Shuttle System AV Shuttle System for BART Station Areas Autonomous Benicia Autonomous Bus Network Technologies Contra Costa Autonomous Shuttle Program I-80 Corridor Overhaul Mountain View AV Shuttle System AV Shuttles at Rockridge and 12th St BART Stations BART Evening Frequency Increase BART Extension from Civic Center to Ocean Beach BART Extension from E. Santa Clara to Eastridge Transit Center BART Extension from Santa Clara to Tasman Drive BART Extension from Hayward to Millbrae BART Extension from Millbrae to San Jose (x4) BART Extension from Millbrae to Santa Clara BART Extension from Milpitas to Martinez (via I-680) BART Extension from Milpitas to -

CORE CAPACITY TRANSIT STUDY SETTING the SCENE BART Caltrain MUNI

CORE CAPACITY TRANSIT STUDY SETTING THE SCENE BART Caltrain MUNI 80 AC Transit Ferry Berkeley Metro Rail 80 Buses Oakland HWY 580 THE CORE San Francisco Alameda Ferries HWY 1 HWY HWY 880 HWY 101 Light Rail Daly City HWY 280 HWY Commuter Rail Since emerging from the 2008 recession, the San Francisco Bay Area has experienced surging growth in population and employment, which has led to increasing transit ridership, especially for trips to and from the San Francisco Core. The current level of demand is placing significant strain on the transit networks serving the Core, with transit providers operating close to or above capacity levels. This limits their ability to be resilient in meeting customer needs, and it creates a ripple effect throughout the entire system during incidents such as service delays and breakdowns. The aim of the Core Capacity Transit Study (CCTS) is to identify transit investments – beyond those operators are already planning – to meet today’s needs and accommodate demand for transit over the next 25 years. BART Caltrain MUNI 80 AC Transit Ferry Berkeley DOR 80 RRI Y CO SBA AN TR Oakland HWY 580 San Francisco THE CORE Alameda HWY 1 HWY SAN FRANCISCO HWY 880 METRO HWY 101 CORRIDOR Daly City The aim of the Core Capacity Transit Study (CCTS) is to HWY 280 HWY identify what additional transit investments are needed to accommodate future employment and housing growth over the short, medium and long term. INTRODUCTION The CCTS is a collaborative effort by seven Bay Area transportation agencies. The study will identify transit solutions for travel to and from the San Francisco Core that support sustainable economic growth and im- prove the quality of life for the region’s residents, visitors, and workforce. -

Solanoexpress Bus Routes Transit Information Fairfield Transportation Center Fairfield

Regional Transit Map Transit REGIONAL TRANSIT DIAGRAM To To Eureka Clearlake Information Mendocino Transit DOWNTOWN AREA TRANSIT CONNECTIONS Authority To Ukiah Lake Oakland Mendocino Transit 12th Street Oakland City Center BART: Greyhound BART, AC Transit FA FA 19th Street Oakland BART: FA BART, AC Transit Cloverdale San Francisco Yolobus To Davis Civic Center/UN Plaza BART: Winters Fairfi eld and Suisun Transit SolanoExpress is Solano SolanoExpress is Solano BART, Muni, Golden Gate Transit, SamTrans Fairfield 101 Embarcadero BART & Ferry Terminal: County’s intercity transit connection. County’s intercity transit connection. BART, Golden Gate Transit, Muni, SamTrans, (FAST) is the local transit system Baylink, Alameda/Oakland Ferry, Alameda Harbor Faireld and Healdsburg Bay Ferry, Blue & Gold Fleet, Amtrak CA Thruway Suisun Transit SolanoExpress routes connect cities SolanoExpress routes connect cities Transit To Sacramento for Fairfi eld and Suisun City and also Mongomery Street BART: Healdsburg BART, Muni, Golden Gate Transit, SamTrans Dixon within the county and provide service within the county and provide service Calistoga Readi- operates many of the SolanoExpress (Operated by FAST) (Operated by SolTrans) Handi Powell Street BART: Transportation Ride Van Calistoga BART, Muni, Golden Gate Transit, SamTrans regional routes. Please visit www.fasttransit. to neighboring counties, BART, and the ferry. to neighboring counties, BART, and the ferry. San Francisco Caltrain at 4th & King: Dixon Windsor Deer Caltrain, Muni, Amtrak CA Thruway org or call 707-422-BUSS (707-422-2877) for For more information, call (800) 535-6883 or For more information, call (800) 535-6883 or Park Transbay Temporary Terminal: Guerneville AC Transit, Muni, Golden Gate Transit, SamTrans, 80 visit www.solanoexpress.com. -

Tcrp Report 94

TRANSIT COOPERATIVE RESEARCH TCRP PROGRAM REPORT 94 Sponsored by the Federal Transit Administration Fare Policies, Structures and Technologies: Update TCRP OVERSIGHT AND PROJECT TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 2003 (Membership as of March 2003) SELECTION COMMITTEE (as of October 2002) OFFICERS CHAIR Chair: Genevieve Giuliano, Director and Prof., School of Policy, Planning, and Development, USC, Los Angeles J. BARRY BARKER Vice Chair: Michael S. Townes, Exec. Dir., Transportation District Commission of Hampton Roads, Hampton, VA Transit Authority of River City Executive Director: Robert E. Skinner, Jr., Transportation Research Board MEMBERS DANNY ALVAREZ MEMBERS Miami-Dade Transit Agency KAREN ANTION MICHAEL W. BEHRENS, Executive Director, Texas DOT Karen Antion Consulting JOSEPH H. BOARDMAN, Commissioner, New York State DOT GORDON AOYAGI SARAH C. CAMPBELL, President, TransManagement, Inc., Washington, DC Montgomery County Government E. DEAN CARLSON, Secretary of Transportation, Kansas DOT JEAN PAUL BAILLY JOANNE F. CASEY, President, Intermodal Association of North America Union Internationale des Transports Publics JAMES C. CODELL III, Secretary, Kentucky Transportation Cabinet RONALD L. BARNES JOHN L. CRAIG, Director, Nebraska Department of Roads Central Ohio Transit Authority BERNARD S. GROSECLOSE, JR., President and CEO, South Carolina State Ports Authority LINDA J. BOHLINGER SUSAN HANSON, Landry University Prof. of Geography, Graduate School of Geography, Clark University HNTB Corp. LESTER A. HOEL, L. A. Lacy Distinguished Professor, Depart. of Civil Engineering, University of Virginia ANDREW BONDS, JR. HENRY L. HUNGERBEELER, Director, Missouri DOT Parsons Transportation Group, Inc. JENNIFER L. DORN ADIB K. KANAFANI, Cahill Prof. and Chair, Dept. of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of FTA California at Berkeley NATHANIEL P.