Caltrain Fare Study Draft Research and Peer Comparison Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commuter Rail System Study

TRANSPORTATION PROGRAMS Commuter Rail System Study Transit Committee March 11, 2010 TRANSPORTATION PROGRAMS Study Purpose Study Requested by MAG Regional Council in 2008 Commuter Rail Study Funding in 2004 RTP Study Feasibility of Commuter Rail Service in MAG Region Ridership Forecasting and Cost Effectiveness Capital and Operating Cost Estimates Vehicle Technology Recommendation Implementation Requirements Copyright © 2009 TRANSPORTATION PROGRAMS Peer Regions ~ Commuter Rail Systems WHAT IS COMMUTER RAIL? Peak Period, Peak Direction Service. Traditionally caries less daily riders than light rail, but for longer distances. Similar market and characteristics with Bus Rapid Transit / Express. SOUNDER-Seattle CALTRAIN-San Francisco ALTAMONT COMMUTER EXPRESS – San Jose Can share ROW and track with freight railroads and can operate concurrently (does not require exclusive right-of-way) . Typically longer station spacing (every 3-7 miles on average) than light rail (1-2 miles) with emphasis on park-and-rides and traditional city CBDs. Locomotive technology (diesel or clean/green hybrid Genset). Passenger coaches (push-pull). Engines and cars meets federally mandated structural requirements for rolling stock crash resistance Larger, heavier profile than light rail vehicles. METROLINK – Los Angeles COASTER – San Diego FRONT RUNNER – Salt Lake City-Ogden Higher max.speed (79mph), slower acceleration and deceleration than light rail. Average speed approx 44mph. Lower capital cost per mile ($10-$20M) due to existing right of way use / reuse. Light -

The Deloitte City Mobility Index Gauging Global Readiness for the Future of Mobility

The Deloitte City Mobility Index Gauging global readiness for the future of mobility By: Simon Dixon, Haris Irshad, Derek M. Pankratz, and Justine Bornstein the Internet of Things, artificial intelligence, and Where should cities other digital technologies to develop and inform go tomorrow? intelligent decisions about people, places, and prod- ucts. A smart city is a data-driven city, one in which Unfortunately, when it comes to designing and municipal leaders have an increasingly sophisti- implementing a long-term vision for future mobil- cated understanding of conditions in the areas they ity, it is all too easy to ignore, misinterpret, or skew oversee, including the urban transportation system. this data to fit a preexisting narrative.1 We have seen In the past, regulators used questionnaires and sur- this play out in dozens of conversations with trans- veys to map user needs. Today, platform operators portation leaders all over the world. To build that can rely on databases to provide a more accurate vision, leaders need to gather the right data, ask the picture in a much shorter time frame at a lower cost. right questions, and focus on where cities should Now, leaders can leverage a vast array of data from go tomorrow. The Deloitte City Mobility Index Given the essential enabling role transportation theme analyses how deliberate and forward- plays in a city’s sustained economic prosperity,2 we thinking a city’s leaders are regarding its future set out to create a new and better way for city of- mobility needs. ficials to gauge the health of their mobility network 3. -

April / May 2018 Metrolink Matters

5 6 APRIL | MAY 2018 LOVE FOR BUILDING THINGS AS A GIRL TURNS INTO A CAREER ON THE RAILROAD ANGELS EXPRESS IS BACK BEGINNING APRIL 2! BLOG METROLINK MATTERS GOES DIGITAL WITH NEW BLOG an’t get enough of Metrolink Matters? Passengers and Elizabeth Lun presenting Metrolink’s structures condition and rehabilitation program to Metrolink Board Members. Lun inside the Santa Fe 3751 steam engine during the Grand stakeholders can now view the latest Metrolink news and Opening Ceremony of the Vincent Grade / Acton station. information on the official new blog, Metrolink Matters. The blog is designed to provide readers with up-to-date or Elizabeth Lun, a childhood passion for building things has turned how working at Metrolink has impacted her professionally and personally. information on a user-friendly, easy-to-access digital platform. into a career overseeing the design and construction of projects that She noted, “My work and personal life balance has improved substantially C F are ushering in a new future for the Metrolink commuter rail system. since joining Metrolink.” Lun added, “I have a deep appreciation for my Metrolink Matters will offer new weekly articles ranging from Trains will operate on the Orange County Line to all weekday home games that job, which allows me to exercise my knowledge and skill while providing Agency news and safety reminders to community outreach start at 7:07 p.m. and on Friday night games on the Inland Empire-Orange As I went through college and early career, I went into transportation me freedom to pursue other passions outside of work. -

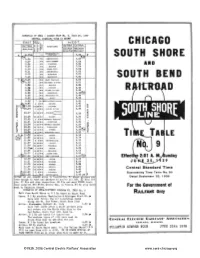

SOUTH SHORE LINE" by A

SCHEI1J1E OF CERA - CSS&SB TRIP HO. 9. June 25. 1939 CENTRAL STANDARD TIla IS SHOWN ~~P~~~tl WE c. T EAST Iof Sld.lli~ S \..J CHICAGO EXTRA ~ ~ ~ i STATIONS EXTRa EXTRA RAILF'AN ~ :i ~~ RAILFAI"I RAJlFAN ~ ~ (AUVAL1iMf) (~PO$ED) SOUTH SHORE ~9.06 --K2 KENSINGTON:~.-. 7.07~ 9.07 16.6 12lth STREET.... 7.06 9.08 UJ.4 PARSONS. .. •. 7.05 AID 9.09 17.2 BRIDGE....... 7.04 9.10 17.Sl FORD CITY..... 7.03 9.11 18.9 HEGEWISCH..... 7.02 9.12 19.1 BURNHAM...... 7.01 9lt15 20.9 HAMMOND.... 7.00 SOUTH BEND B t ~ 9.25 ...... 22.S ...EAST CIDCAGO... 6.55 '.!!I 9.32 23.8.CALUMET X-OVER. 6.51 9.33 24.5 EMPIRE...... 6.50 9.3a 25.3 CUDAHY....... 6.49 9.31 26.8 CLARK X-OVER... 6.48 9.38 29.2 AMBRIDGE..... 6.45~ 9.39 30.2 BUCHANAN ST.. .. 6.44 9.40 30.8 GARY.. 6.43 9.42. 31.7END DOUBLE TRACK 6.42 :9.45 5 34.6 MILLER... .... 6.40 ~ . ~ 5 C (I'~0.10 113166 86.7 WAGNER...... 6. 38 ~ 0.1' 7 14 39.2 OGDEN DUNES... 6. 36 ~ ~ 1 {west End Ci 10.? 30 i2 to.2 WILBON East End 6.35 ~ ~ 10.. 18 82 48 18.1 BAILEY ....... 6. 32 ~ I 10.19 i 6 ".6 .MINERAL SPRINGS. 6.31 t 10.21 86 62 46.4 .....FORSY~'HE..... 6. 30 ~ ~ 10.24 10 20 60.6. BEVERLY SHORES. 6 27 ~ 10.25 48 71l 61.i TAMARACK.... -

Pacific Surfliner-San Luis Obispo-San Diego-October282019

PACIFIC SURFLINER® PACIFIC SURFLINER® SAN LUIS OBISPO - LOS ANGELES - SAN DIEGO SAN LUIS OBISPO - LOS ANGELES - SAN DIEGO Effective October 28, 2019 Effective October 28, 2019 ® ® SAN LUIS OBISPO - SANTA BARBARA SAN LUIS OBISPO - SANTA BARBARA VENTURA - LOS ANGELES VENTURA - LOS ANGELES ORANGE COUNTY - SAN DIEGO ORANGE COUNTY - SAN DIEGO and intermediate stations and intermediate stations Including Including CALIFORNIA COASTAL SERVICES CALIFORNIA COASTAL SERVICES connecting connecting NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Visit: PacificSurfliner.com Visit: PacificSurfliner.com Amtrak.com Amtrak.com Amtrak is a registered service mark of the National Railroad Passenger Corporation. Amtrak is a registered service mark of the National Railroad Passenger Corporation. National Railroad Passenger Corporation, Washington Union Station, National Railroad Passenger Corporation, Washington Union Station, One Massachusetts Ave. N.W., Washington, DC 20001. One Massachusetts Ave. N.W., Washington, DC 20001. NRPS Form W31–10/28/19. Schedules subject to change without notice. NRPS Form W31–10/28/19. Schedules subject to change without notice. page 2 PACIFIC SURFLINER - Southbound Train Number u 5804 5818 562 1564 564 1566 566 768 572 1572 774 Normal Days of Operation u Daily Daily Daily SaSuHo Mo-Fr SaSuHo Mo-Fr Daily Mo-Fr SaSuHo Daily 11/28,12/25, 11/28,12/25, 11/28,12/25, Will Also Operate u 1/1/20 1/1/20 1/1/20 11/28,12/25, 11/28,12/25, 11/28,12/25, Will Not Operate u 1/1/20 1/1/20 1/1/20 B y B y B y B y B y B y B y B y B y On Board Service u låO låO låO låO låO l å O l å O l å O l å O Mile Symbol q SAN LUIS OBISPO, CA –Cal Poly 0 >v Dp b3 45A –Amtrak Station mC ∑w- b4 00A l6 55A Grover Beach, CA 12 >w- b4 25A 7 15A Santa Maria, CA–IHOP® 24 >w b4 40A Guadalupe-Santa Maria, CA 25 >w- 7 31A Lompoc-Surf Station, CA 51 > 8 05A Lompoc, CA–Visitors Center 67 >w Solvang, CA 68 >w b5 15A Buellton, CA–Opp. -

California State Rail Plan 2005-06 to 2015-16

California State Rail Plan 2005-06 to 2015-16 December 2005 California Department of Transportation ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER, Governor SUNNE WRIGHT McPEAK, Secretary Business, Transportation and Housing Agency WILL KEMPTON, Director California Department of Transportation JOSEPH TAVAGLIONE, Chair STATE OF CALIFORNIA ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER JEREMIAH F. HALLISEY, Vice Chair GOVERNOR BOB BALGENORTH MARIAN BERGESON JOHN CHALKER JAMES C. GHIELMETTI ALLEN M. LAWRENCE R. K. LINDSEY ESTEBAN E. TORRES SENATOR TOM TORLAKSON, Ex Officio ASSEMBLYMEMBER JENNY OROPEZA, Ex Officio JOHN BARNA, Executive Director CALIFORNIA TRANSPORTATION COMMISSION 1120 N STREET, MS-52 P. 0 . BOX 942873 SACRAMENTO, 94273-0001 FAX(916)653-2134 (916) 654-4245 http://www.catc.ca.gov December 29, 2005 Honorable Alan Lowenthal, Chairman Senate Transportation and Housing Committee State Capitol, Room 2209 Sacramento, CA 95814 Honorable Jenny Oropeza, Chair Assembly Transportation Committee 1020 N Street, Room 112 Sacramento, CA 95814 Dear: Senator Lowenthal Assembly Member Oropeza: On behalf of the California Transportation Commission, I am transmitting to the Legislature the 10-year California State Rail Plan for FY 2005-06 through FY 2015-16 by the Department of Transportation (Caltrans) with the Commission's resolution (#G-05-11) giving advice and consent, as required by Section 14036 of the Government Code. The ten-year plan provides Caltrans' vision for intercity rail service. Caltrans'l0-year plan goals are to provide intercity rail as an alternative mode of transportation, promote congestion relief, improve air quality, better fuel efficiency, and improved land use practices. This year's Plan includes: standards for meeting those goals; sets priorities for increased revenues, increased capacity, reduced running times; and cost effectiveness. -

Travel Characteristics of Transit-Oriented Development in California

Travel Characteristics of Transit-Oriented Development in California Hollie M. Lund, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Urban and Regional Planning California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Robert Cervero, Ph.D. Professor of City and Regional Planning University of California at Berkeley Richard W. Willson, Ph.D., AICP Professor of Urban and Regional Planning California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Final Report January 2004 Funded by Caltrans Transportation Grant—“Statewide Planning Studies”—FTA Section 5313 (b) Travel Characteristics of TOD in California Acknowledgements This study was a collaborative effort by a team of researchers, practitioners and graduate students. We would like to thank all members involved for their efforts and suggestions. Project Team Members: Hollie M. Lund, Principle Investigator (California State Polytechnic University, Pomona) Robert Cervero, Research Collaborator (University of California at Berkeley) Richard W. Willson, Research Collaborator (California State Polytechnic University, Pomona) Marian Lee-Skowronek, Project Manager (San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit) Anthony Foster, Research Associate David Levitan, Research Associate Sally Librera, Research Associate Jody Littlehales, Research Associate Technical Advisory Committee Members: Emmanuel Mekwunye, State of California Department of Transportation, District 4 Val Menotti, San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit, Planning Department Jeff Ordway, San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit, Real Estate Department Chuck Purvis, Metropolitan Transportation Commission Doug Sibley, State of California Department of Transportation, District 4 Research Firms: Corey, Canapary & Galanis, San Francisco, California MARI Hispanic Field Services, Santa Ana, California Taylor Research, San Diego, California i Travel Characteristics of TOD in California ii Travel Characteristics of TOD in California Executive Summary Rapid growth in the urbanized areas of California presents many transportation and land use challenges for local and regional policy makers. -

REDLANDS PASSENGER RAIL PROJECT (ARROW) Plan. Build

REDLANDS PASSENGER RAIL PROJECT (ARROW) Arrow connects to • Mountain Transit San Bernardino – 210 • Omnitrans to CSUSB to Downtown Station • Pass Transit • Victor Valley Transit Overview San Bernardino Santa Fe Depot The Redlands Passenger Rail Project is an innovative nine-mile regional Tippecanoe Metrolink connects to Station N • Los Angeles INTERSTATE rail project that provides additional transportation choices through the CALIFORNIA • Orange County 10 University introduction of a new rail service, known as the Arrow, which integrates • San Diego Station • Riverside INTERSTATE • Ventura CALIFORNIA conveniently with other modes of transportation such as auto, bus and 215 Esri to Loma Linda University Station bicycle. Medical Center Redlands – N Downtown Station The Arrow will connect San Bernardino and Redlands and will offer residents, businesses and visitors a new commuting option to travel to a variety of leisure, education, healthcare and other destinations. Diesel Multiple Units (DMUs) have been identified as the preferred vehicle to provide primary service for the project. The DMUs are powered by an on-board low-emission, Clean Diesel engine which are smaller, quieter, more Funding efficient, and cheaper to operate than standard locomotive haul coaches, similar to Metrolink. DMUs work interoperably on the same track as Metrolink FEDERAL $86.0 Million and freight train services which allows for all three train services to use the STATE $164.6 Million same track in the existing corridor. LOCAL $109.1 Million (Includes Measure I) In addition to local commuter service, a Metrolink locomotive hauled coach train will also provide round trip express service from Redlands-to-Los TOTAL $359.7 Million Angeles each morning with return trip from Los Angeles-to-Redlands each evening. -

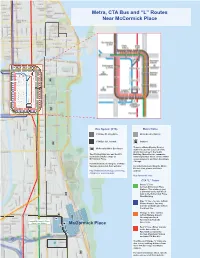

Metra, CTA Bus and “L” Routes Near Mccormick Place

Metra, CTA Bus and “L” Routes Near McCormick Place Bus System (CTA) Metra Trains CTA Bus #3, King Drive Metra Electric District CTA Bus #21, Cermak Stations There is a Metra Electric District McCormick Place Bus Stops station located on Level 2.5 of the Grand Concourse in the South The #3 King Drive bus and the #21 Building. Metra Electric commuter Cermak bus makes stops at railroad provides direct service within McCormick Place. seven minutes to and from downtown Chicago. For information on riding the CTA Bus System, please visit their website: For information on riding the Metra Electric Line, please visit their http://www.transitchicago.com/riding_ website: cta/service_overview.aspx http://metrarail.com/ CTA “L” Trains Green “L” line Cermak-McCormick Place Station - This station is just a short two and a half block walk to the McCormick Place West Building Blue “L” line - Service to/from O’Hare Airport. You may transfer at Clark/Lake to/from the Green line. Orange “L” line - Service to/from Midway Airport. You may transfer at Roosevelt to/from the Cermak-McCormick Place Green Line. Green Line Station McCormick Place Red “L” line - Either transfer to the Green Line at Roosevelt or exit at the Cermak-Chinatown Station and take CTA Bus #21 The Blue and Orange “L” trains are also in easy walking distance from most CTA Bus stops and Metra stations. For more information about specific routes, please visit their website:. -

WEST LAKE CORRIDOR PROJECT MAP - HAMMOND, in to DYER, in CHICAGOCHICAGO WHITINGWHITING Lalakeke 9090 Ccalumetalumet Wwolfolf La Lakeke 1212 4141

West Lake Corridor | Project Fact Sheet | August 2020 - HAMMOND, IN TO DYER, IN WEST LAKE CORRIDOR PROJECT MAP CHICAGOCHICAGO WHITINGWHITING LaLakeke 9090 CCalumetalumet WWolfolf La Lakeke 1212 4141 912912 94 Little Calumet River Little Calumet R iver HEGEWISCHHEGEWISCH PulaskiPulaski Park Park PoPowderwder EASTEAST HHornorn L aLakeke HAMMONDHAMMOND CHICHICAGOCAGO BURNHAMBurnhamBurnham BURNHAMEElementarylementary SSchoolchool HHermitermit StSt Casimir Casimir School School DOLTONDOLTON ParkPark 2020 BEGIN IMPROVEMENTIMPROVEMENT 312312 WWashingtonashington Ir vingIrving 83 HAMMONDHAMMOND GGATEWAYATEWAY ElemeElementaryntary School School 9090 EASTEAST CHICAGO CHICAGO 4141 CalumetCalumet R River d an iv Gr Grand er CCALUMETALUMET CICITYTY HeHenrynry W W HarrisonHarrison P arkPark EggersEggers School School y a DrDr MLK MLK Park Park w n Memorial Park e OakOak Hill Hill Hammond Memorial Park e Hammond r G Cemetery Cemetery HighHigh School School 6 m Maywood a Maywood h n ElemeElementaryntary School School r HAMMOND u HAMMOND B Burnham Greenway Burnham Concordia 94 l Concordia 94 i a r CemeCemeterytery T SOUTH n 152 o 152 VVeteranseterans P arkPark n EdisonEdison Park Park HOLLANDHOLLAND o M Monon Trail Monon ThomasThomas Edison Edison ReReavisavis SOUTHSOUTHElementary SHAMMOND choolHAMMOND EElementarylementary Elementary School SSchoolchool THORNTON 94 80 THORNTON Bock Park LionsLions P arkPark Bock Park Y Y T T 94 80 P Riverside Park 94 80 ennsyPennsy G rGreenway Little C Riverside Park Littlealumet Calumet OUN OUN C C Trail een RiRiverver -

Big Freight Railroads to Miss Safety Technology Deadline

Big Freight railroads to miss safety technology deadline FILE - In this June 4, 2014 file photo, a Norfolk Southern locomotive moves along the tracks in Norfolk, Va. Three of the biggest freight railroads operating in the U.S. have told telling the government they won’t make a 2018 deadline to start using safety technology intended to prevent accidents like the deadly derailment of an Amtrak train in Philadelphia last May. Norfolk Southern, Canadian National Railway and CSX Transportation and say they won’t be ready until 2020, according to a list provided to The Associated Press by the Federal Railroad Administration. Steve Helber, File AP Photo BY JOAN LOWY, Associated Press WASHINGTON Three of the biggest freight railroads operating in the U.S. have told the government they won't meet a 2018 deadline to start using safety technology intended to prevent accidents like the deadly derailment of an Amtrak train in Philadelphia last May. Canadian National Railway, CSX Transportation and Norfolk Southern say they won't be ready until 2020, according to a list provided to The Associated Press by the Federal Railroad Administration. Four commuter railroads — SunRail in Florida, Metra in Illinois, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority and Trinity Railway Express in Texas — also say they'll miss the deadline. The technology, called positive train control or PTC, relies on GPS, wireless radio and computers to monitor train positions and automatically slow or stop trains that are in danger of colliding, derailing due to excessive speed or about to enter track where crews are working or that is otherwise off limits. -

Sounder Commuter Rail (Seattle)

Public Use of Rail Right-of-Way in Urban Areas Final Report PRC 14-12 F Public Use of Rail Right-of-Way in Urban Areas Texas A&M Transportation Institute PRC 14-12 F December 2014 Authors Jolanda Prozzi Rydell Walthall Megan Kenney Jeff Warner Curtis Morgan Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ 8 List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. 9 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 10 Sharing Rail Infrastructure ........................................................................................................ 10 Three Scenarios for Sharing Rail Infrastructure ................................................................... 10 Shared-Use Agreement Components .................................................................................... 12 Freight Railroad Company Perspectives ............................................................................... 12 Keys to Negotiating Successful Shared-Use Agreements .................................................... 13 Rail Infrastructure Relocation ................................................................................................... 15 Benefits of Infrastructure Relocation ...................................................................................