Assessing Opportunities for Intelligent Transportation Systems in California's Passenger Intermodal Operations and Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commuter Rail System Study

TRANSPORTATION PROGRAMS Commuter Rail System Study Transit Committee March 11, 2010 TRANSPORTATION PROGRAMS Study Purpose Study Requested by MAG Regional Council in 2008 Commuter Rail Study Funding in 2004 RTP Study Feasibility of Commuter Rail Service in MAG Region Ridership Forecasting and Cost Effectiveness Capital and Operating Cost Estimates Vehicle Technology Recommendation Implementation Requirements Copyright © 2009 TRANSPORTATION PROGRAMS Peer Regions ~ Commuter Rail Systems WHAT IS COMMUTER RAIL? Peak Period, Peak Direction Service. Traditionally caries less daily riders than light rail, but for longer distances. Similar market and characteristics with Bus Rapid Transit / Express. SOUNDER-Seattle CALTRAIN-San Francisco ALTAMONT COMMUTER EXPRESS – San Jose Can share ROW and track with freight railroads and can operate concurrently (does not require exclusive right-of-way) . Typically longer station spacing (every 3-7 miles on average) than light rail (1-2 miles) with emphasis on park-and-rides and traditional city CBDs. Locomotive technology (diesel or clean/green hybrid Genset). Passenger coaches (push-pull). Engines and cars meets federally mandated structural requirements for rolling stock crash resistance Larger, heavier profile than light rail vehicles. METROLINK – Los Angeles COASTER – San Diego FRONT RUNNER – Salt Lake City-Ogden Higher max.speed (79mph), slower acceleration and deceleration than light rail. Average speed approx 44mph. Lower capital cost per mile ($10-$20M) due to existing right of way use / reuse. Light -

California State Rail Plan 2005-06 to 2015-16

California State Rail Plan 2005-06 to 2015-16 December 2005 California Department of Transportation ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER, Governor SUNNE WRIGHT McPEAK, Secretary Business, Transportation and Housing Agency WILL KEMPTON, Director California Department of Transportation JOSEPH TAVAGLIONE, Chair STATE OF CALIFORNIA ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER JEREMIAH F. HALLISEY, Vice Chair GOVERNOR BOB BALGENORTH MARIAN BERGESON JOHN CHALKER JAMES C. GHIELMETTI ALLEN M. LAWRENCE R. K. LINDSEY ESTEBAN E. TORRES SENATOR TOM TORLAKSON, Ex Officio ASSEMBLYMEMBER JENNY OROPEZA, Ex Officio JOHN BARNA, Executive Director CALIFORNIA TRANSPORTATION COMMISSION 1120 N STREET, MS-52 P. 0 . BOX 942873 SACRAMENTO, 94273-0001 FAX(916)653-2134 (916) 654-4245 http://www.catc.ca.gov December 29, 2005 Honorable Alan Lowenthal, Chairman Senate Transportation and Housing Committee State Capitol, Room 2209 Sacramento, CA 95814 Honorable Jenny Oropeza, Chair Assembly Transportation Committee 1020 N Street, Room 112 Sacramento, CA 95814 Dear: Senator Lowenthal Assembly Member Oropeza: On behalf of the California Transportation Commission, I am transmitting to the Legislature the 10-year California State Rail Plan for FY 2005-06 through FY 2015-16 by the Department of Transportation (Caltrans) with the Commission's resolution (#G-05-11) giving advice and consent, as required by Section 14036 of the Government Code. The ten-year plan provides Caltrans' vision for intercity rail service. Caltrans'l0-year plan goals are to provide intercity rail as an alternative mode of transportation, promote congestion relief, improve air quality, better fuel efficiency, and improved land use practices. This year's Plan includes: standards for meeting those goals; sets priorities for increased revenues, increased capacity, reduced running times; and cost effectiveness. -

Caltrain Fare Study Draft Research and Peer Comparison Report

Caltrain Fare Study Draft Research and Peer Comparison Report Public Review Draft October 2017 Caltrain Fare Study Draft Research and Peer Comparison October 2017 Research and Peer Review Research and Peer Review .................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 2 A Note on TCRP Sources ........................................................................................................................................... 2 Elasticity of Demand for Commuter Rail ............................................................................... 3 Definition ........................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Commuter Rail Elasticity ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Comparison with Peer Systems ............................................................................................ 4 Fares ................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Employer Programs .................................................................................................................................................. -

Travel Characteristics of Transit-Oriented Development in California

Travel Characteristics of Transit-Oriented Development in California Hollie M. Lund, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Urban and Regional Planning California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Robert Cervero, Ph.D. Professor of City and Regional Planning University of California at Berkeley Richard W. Willson, Ph.D., AICP Professor of Urban and Regional Planning California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Final Report January 2004 Funded by Caltrans Transportation Grant—“Statewide Planning Studies”—FTA Section 5313 (b) Travel Characteristics of TOD in California Acknowledgements This study was a collaborative effort by a team of researchers, practitioners and graduate students. We would like to thank all members involved for their efforts and suggestions. Project Team Members: Hollie M. Lund, Principle Investigator (California State Polytechnic University, Pomona) Robert Cervero, Research Collaborator (University of California at Berkeley) Richard W. Willson, Research Collaborator (California State Polytechnic University, Pomona) Marian Lee-Skowronek, Project Manager (San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit) Anthony Foster, Research Associate David Levitan, Research Associate Sally Librera, Research Associate Jody Littlehales, Research Associate Technical Advisory Committee Members: Emmanuel Mekwunye, State of California Department of Transportation, District 4 Val Menotti, San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit, Planning Department Jeff Ordway, San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit, Real Estate Department Chuck Purvis, Metropolitan Transportation Commission Doug Sibley, State of California Department of Transportation, District 4 Research Firms: Corey, Canapary & Galanis, San Francisco, California MARI Hispanic Field Services, Santa Ana, California Taylor Research, San Diego, California i Travel Characteristics of TOD in California ii Travel Characteristics of TOD in California Executive Summary Rapid growth in the urbanized areas of California presents many transportation and land use challenges for local and regional policy makers. -

Community Meeting #2

HIGH ST HIGH ST LINCOLN STREET LINCOLN STREET DRISCOLL DRISCOLL MAIN STREET MAIN STREET ROAD Alternative A: Key Elements ROAD Alternative C: Key Elements ROBER ROBER ARD A PRIVATE PROPERTY ARD C ON BOULEV ON BOULEV WASHINGT TS WITH POTENTIAL FOR WASHINGT TS FUTURE COMMERCIAL A A VENUE RETAIL DEVELOPMENT VENUE HISTORIC GALLEGOS WINERY PARK OSGOOD ROAD • Urban with Parking BART station access type OSGOOD ROAD • Balanced Intermodal BART station access type MAINTENANCE-OF-W MAINTENANCE-OF-W HISTORIC GALLEGOS • Provides a pedestrian bridge from the corner of the WINERY PARK • P r o v i d e s a p e d e s t r i a n b r i d g e o v e r O s g o o d R o a d b e t w e e n t h e A STAFF, POLICE, Y A (MOW) Y Washington Boulevard/Osgood Road intersection to the STAFF, POLICE, (MOW) MAINTENANCE, AND MAINTENANCE, AND TREASURY PARKING TREASURY PARKING ACCESS ROAD ACCESS ROAD parking structure and the concourse concourse PICK UP AND PICK UP AND DROP OFF AREA SECTION CUT DROP OFF AREA SECTION CUT SEE BELOW SEE BELOW PREFERRED UNION P PREFERRED UNION P ELEVATED PEDESTRIAN PARKING - ADA, PARKING STRUCTURE PARKING - ADA, • Pedestrian ramp on west side of station site CONNECTION TO • Includes two new signalized intersections on Osgood Road MOTORCYCLE, & (GROUND+3 LEVELS) MOTORCYCLE, & ELECTRIC VEHICLES CONCOURSE ACIFIC RAILROAD (UPRR) ELECTRIC VEHICLES ACIFIC RAILROAD (UPRR) SOLAR ARRAY BUS TRANSIT CENTER (PENDING FURTHER AND NEW BUS STOPS FEASIBILITY STUDY) BICYCLE PARKING BICYCLE PARKING GATEWAY PLAZA AT THE RAIN GARDENS WASHINGTON ENTRY • Provides a single -

Keeping Southern California's Future on Track

Keeping Southern California’s 25Future on Track CONTENTS Message from the Board Chair .........................1 CEO’s Message .....................................................3 A Quarter Century of Moving People: The Metrolink Story .............................................5 How It All Began ................................................19 Metrolink’s Top Priority: Safety .......................27 WHO WE ARE Environment ........................................................31 Metrolink is Southern California’s regional commuter rail service in its Metrolink Relieves Driving Stress ...................35 25th year of operation. Metrolink is governed by The Southern California Regional Rail Authority (SCRRA), Board Members Past and Present ..................40 a joint powers authority made up of an 11-member board representing Metrolink Pioneering Staff the transportation commissions of Still on Board ......................................................47 Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino and Ventura counties. Metrolink Employees Metrolink operates seven routes Put Customers First ...........................................48 through a six-county, 538-route-mile network with 60 stations. Facts at a Glance ...............................................50 For more information, including how to ride, go to www.metrolinktrains.com MISSION STATEMENT Our mission is to provide safe, efficient, dependable and on-time transportation service that offers outstanding customer experience and enhances quality of life. For -

San Francisco Transportation Code 5/28/15, 7:37 PM

San Francisco Transportation Code 5/28/15, 7:37 PM CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO MUNICIPAL CODE TRANSPORTATION CODE The San Francisco Municipal Code is current through Ordinance 107-13, File No. 130070, approved June 13, 2013, effective July 13, 2013. Division I of the Transportation Code was last amended by Ordinance 101-13, File No. 130318, approved June 10, 2013, effective July 10, 2013, operative June 1, 2013. Division II of the Transportation Code was last amended by SFMTA Board Resolution No. 13-174, adopted June 18, 2013, effective July 19, 2013. The San Francisco Municipal Code: Environment Code Port Code Charter Fire Code Public Works Code Administrative Code Health Code Subdivision Code Building, Electrical, Housing, Mechanical and Plumbing Codes Municipal Transportation Code Elections Code Business and Tax Regulations Code Zoning Maps Park Code Campaign and Governmental Conduct Code Comprehensive Planning Code Ordinance Table Police Code AMERICAN LEGAL PUBLISHING CORPORATION 432 Walnut Street, Suite 1200 Cincinnati, Ohio 45202-3909 (800) 445-5588 Fax: (513) 763-3562 Email: [email protected] www.amlegal.com PREFACE TO THE TRANSPORTATION CODE Proposition A, titled "Transit Reform, Parking Regulation and Emissions Reductions," was adopted by the voters on November 7, 2007. Proposition A amended the San Francisco Charter to give the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency additional authority in several areas, such as approving contracts, hiring, setting employee pay rates and proposing revenue measures. Proposition A also expanded MTA power to adopt many parking and traffic regulations, and to install many traffic control devices that had previously required the approval of the Board of Supervisors. -

PATCO New Automated Fare Collection System, Smart Card Or Magnetic- Your Choice

PATCO New Automated Fare Collection System, Smart card or Magnetic- Your choice PATCO’s new fare collection system will feature the FREEDOM card, which will revolutionize how customers purchase their fares and travel on the PATCO system. The FREEDOM card is a smart card that will provide a high level of convenience and reliability to customers who use PATCO consistently. For customers who do not opt to use the FREEDOM card or who use PATCO infrequently, new magnetic tickets will be available. In PATCO’s current fare system, plastic tickets that use first generation magnetic technology are used. Although that technology was state of the art several decades ago, the technology is outdated and the tickets are prone to damage by devices commonly found in today’s environment. Unlike the current tickets, which are re-encoded numerous times for use after being captured by the fare gates, the new magnetic tickets will be paper tickets and will not be reused after capture. The new magnetic tickets can be purchased using either cash or coins. This means that customers choosing to purchase a ticket will not have to first stop at a change machine to convert their bills to coins. Both one- and two-ride tickets can be purchased from all new ticket vending machines located outside the fare gates. A customer wishing to purchase a magnetic ticket will simply select the prompt on the ticket vending machine screen for purchase of a ticket and then select the destination and whether a single ride or double ride ticket is desired. The ticket vending machine will list the price of the purchase. -

Macarthur BART Station Access Study Example

Seattle: Local Day - Connectivity San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District October 23, 2013 1 Framing the Issue • Recognize that BART and surrounding land will be used for transit-oriented development (TOD) • Need to provide sustainable modes of access to grow ridership • Transit agency does not control most access – Walk: Sidewalks, entitling TOD – local jurisdiction – Bike: Bike paths, roadways – local jurisdiction – Transit: Local bus operators – Shuttles: Local operators • Access we do control – parking !!! 2 BART’s Approach • Conduct Access Study as part of TOD entitlement process • Employ Joint Powers Authorities to align transit and local objectives on access • Transportation Demand Management • Developer provision of transit passes 3 BART Access Study Objectives • Conduct access study as part of Environmental Impact Report (California – CEQA) • Examine all modes of access in concert with local jurisdiction and bus operators – Pedestrian - Bicycle – Transit - Auto • Create tiered strategies – Tier 0: TOD plan – connect faregates to surrounding land use – Tier 1: Most feasible, cost-effective – Tier 2: Likely feasible, some barriers, require coordinator – Tier 3: Long-term, further study required • Create Access Program – Short-term improvements – Longer-term improvements 4 – Approach to ensure Access Program remains current MacArthur BART Station Access Study Example 5 Access Study for MacArthur BART Station • Existing Conditions • Pedestrian • Transit, shuttles • Bicycle • Auto • Tiered Strategies • Funding • TOD Changes -

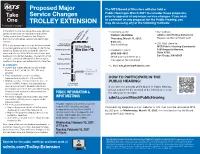

TROLLEY EXTENSION May Do So Using Any of the Following Methods: Post Until 3/12/2021

Proposed Major The MTS Board of Directors will also hold a Public Hearing in March 2021 to consider these proposals, Take Service Changes prior to approval of any major service changes. If you wish One to comment on any proposal for the Public Hearing, you TROLLEY EXTENSION may do so using any of the following methods: Post Until 3/12/2021 In Fall 2021, the UC San Diego Blue Line light rail • Testimony at the • Our website, extension will open and expand the San Diego sdmts.com/Trolley-Extension Trolley system from Downtown San Diego to PUBLIC HEARING: the UTC Transit Center, serving nine new Trolley Thursday, March 11, 2021, Please use the comment form UC SAN DIEGO UC San DiegoExecutive DriveUTC stations. Health La Jolla 9:00 a.m. UC San Diego See box below. • U.S. Mail. Send to: MTS is also proposing to change the bus network Central Campus MTS Public Hearing Comments to connect people and communities to the Trolley VA Medical Center extension. Extensive rider and public outreach Blue Line • Telephone Hotline: 1255 Imperial Avenue, Suite 1000, was conducted in 2018-2019 to collect ideas and Nobel Drive (619) 595-4912 feedback on potential changes.. The results of that (leave your comments as a San Diego, CA 92101 outreach, combined with detailed data analysis, Balboa Avenue resulted in the proposals detailed in this Take One. message on the voicemail) Clairemont Drive IN SUMMARY: • E-Mail: [email protected] • Current bus routes affected would include: Tecolote Road Routes 8, 9, 27, 30, 44, 50, 105, 150, and Green Line 201/202. -

Transportation Air Quality Conformity Analysis for the Amended Plan Bay

The Final Transportation-Air Quality Conformity Analysis for the Amended Plan Bay Area 2040 and the 2021 Transportation Improvement Program February 2021 Bay Area Metro Center 375 Beale Street San Francisco, CA 94105 (415) 778-6700 phone [email protected] e-mail www.mtc.ca.gov web Project Staff Matt Maloney Acting Director, Planning Therese Trivedi Assistant Director Harold Brazil Senior Planner, Project Manager 2021 Transportation Improvement Program Conformity Analysis Page | i Table of Contents I. Summary of Conformity Analysis ...................................................................................................... 1 II. Transportation Control Measures .................................................................................................... 7 History of Transportation Control Measures .............................................................................. 7 Status of Transportation Control Measures................................................................................ 9 III. Response to Public Comments ...................................................................................................... 12 IV. Conformity Findings ...................................................................................................................... 13 Appendix A. List of Projects in the 2021 Transportation Improvement Program Appendix B. List of Projects in Amended Plan Bay Area 2040 2021 Transportation Improvement Program Conformity Analysis Page | ii I. Summary of Conformity Analysis The -

Clipper FAQ Where Can I Buy a Clipper Card? All BART Stations Have Clipper Vending Machines Which Accept Cash, Credit Cards

Clipper FAQ Where can I buy a Clipper card? All BART Stations have Clipper vending machines which accept cash, credit cards and debit cards as payment. You can add cash value to Clipper cards at all BART ticket machines. Clipper cards can be ordered online at www.clippercard.com. Many retail outlets throughout the region also sell Clipper cards. How do I use Clipper? When you get to the fare gate, simply “tag and go” to pay for your ride. The correct fare will automatically be deducted. You must tag your card during every station entry and exit. How much does a Clipper card cost? There is a one-time $3.00 acquisition fee for a Clipper card. Clipper will waive this fee if the buyer signs up for Autoload at the time of purchase online at www.clippercard.com. Youth and senior cards are free. Can I buy a discounted Clipper card? You can get a 6.25% discount on BART rides ($45 for a $48 ticket or $60 for a $64 ticket) when you load BART HVD (High Value Discount) tickets on your adult Clipper card. HVD tickets are only valid for fare payment on BART. HVD tickets can only be loaded to your card through Autoload and participating transit benefit programs. You cannot purchase HVD tickets at Clipper retailers or Customer Service Centers, transit agency ticket offices or ticket machines. The HVD balance on your Clipper card cannot exceed $250. Youth 5-18 years old get 50% off with a youth Clipper card. Seniors age 65 and over get 62.5% off with a Senior Clipper card.