Analytical Report of Research Within the Project “Underaged, Overlooked

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Territorial Structure of the West-Ukrainian Region Settling System

Słupskie Prace Geograficzne 8 • 2011 Vasyl Dzhaman Yuriy Fedkovych National University Chernivtsi (Ukraine) TERRITORIAL STRUCTURE OF THE WEST-UKRAINIAN REGION SETTLING SYSTEM STRUKTURA TERYTORIALNA SYSTEMU ZASIEDLENIA NA TERYTORIUM ZACHODNIEJ UKRAINY Zarys treści : W artykule podjęto próbę charakterystyki elementów struktury terytorialnej sys- temu zasiedlenia Ukrainy Zachodniej. Określono zakres organizacji przestrzennej tego systemu, uwzględniając elementy społeczno-geograficzne zachodniego makroregionu Ukrainy. Na podstawie przeprowadzonych badań należy stwierdzić, że struktura terytorialna organizacji produkcji i rozmieszczenia ludności zachodniej Ukrainy na charakter radialno-koncentryczny, co jest optymalnym wariantem kompozycji przestrzennej układu społecznego regionu. Słowa kluczowe : system zaludnienia, Ukraina Zachodnia Key words : settling system, West Ukraine Problem Statement Improvement of territorial structure of settling systems is among the major prob- lems when it regards territorial organization of social-geographic complexes. Ac- tuality of the problem is evidenced by introducing of the Territory Planning and Building Act, Ukraine, of 20 April 2000, and the General Scheme of Ukrainian Ter- ritory Planning Act, Ukraine, of 7 February 2002, both Acts establishing legal and organizational bases for planning, cultivation and provision of stable progress in in- habited localities, development of industrial, social and engineering-transport infra- structure ( Territory Planning and Building ... 2002, General Scheme of Ukrainian Territory ... 2002). Initial Premises Need for improvement of territorial organization of productive forces on specific stages of development delineates a circle of problems that require scientific research. 27 When studying problems of settling in 50-70-ies of the 20 th century, national geo- graphical science focused the majority of its attention upon separate towns and cit- ies, in particular, upon limitation of population increase in big cities, and to active growth of mid and small-sized towns. -

Intraregional Variability and Place-Specific Electoral Behavior in Ukraine

4 Економічна та соціальна географія. – Київ, 2018. – Вип. 80 INTRAREGIONAL VARIABILITY AND PLACE-SPECIFIC ELECTORAL BEHAVIOR IN UKRAINE Mykola DOBYSH Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Ukraine [email protected] Abstract: The paper criticizes electoral geography studies of Ukraine, where the territory of the country is artificially divided into a number of regions following administrative divisions. The study reveals intraregional variability in the territorial patterns of voting behavior in Ukraine in 2002-2014. Zakarpattya, Chernivtsi, Sumy, Chernigiv, and Zhytomyr oblasts have the highest intraregional variance of electoral preferences for conventional “national-democratic” and “Communists and pro- Russian” political parties. All oblasts of Ukraine have internal variations of voting behavior. It was studied based on electoral results data for rayons and cities with special administrative status (n=675). Scatterplot with a time scale, filters for oblasts and rayons/cities, and the opportunity to draw electoral preferences trajectories from 2002 to 2014 parliamentary elections was used as a research instrument. The study also reveals region-specific voting patterns of cities and territorial outliers, which are bounded by administrative borders places with unique voting behavior. The paper accentuates place-specific and region-as- context understanding of electoral behavior as an essential conceptual framework for the further electoral geography studies of Ukraine. Key words: electoral geography of Ukraine, intraregional -

Research and Achievements for New Electrochemical Biosensors

Food and Environment Safety - Journal of Faculty of Food Engineering, Ştefan cel Mare University - Suceava Year IX, No2 - 2010 RESEARCH AND ACHIEVEMENTS FOR NEW ELECTROCHEMICAL BIOSENSORS Gheorghe GUTT1, Yarema TEVTUL2, Andrei GUTT1, Alina PSIBILSCHI1 1 Faculty of Food Engineering, Stefan cel Mare University, Street. Universitatii no.13, 720229, Suceava, Romania, [email protected] 2Yuriy Fedkovych National University of Chernivtsi, Kotsiubynsky St., 2, Chernivtsi, 58012 Ukraine Abstract. The paper presents results and research of a team involved in instrumental analysis from Faculty of Food Engineering of Suceava University in biosensors field, for food, health and environment issues. Starting from previous achievements were developed electrochemical performance biosensors, extensive use, for analysis both in situ as well as in the laboratory, mainly in pursuing the universal use of such equipment in all reactions using as catalyst type oxidase enzymes. Another aim was to increase sensitivity of measurement and accuracy of such equipment, also by proposed solutions were removed single-use kits, commonly used in the realization of biosensors by using watertight vials containing oxidase which is enough for hundreds of tests. Combined biosensor described in this paper has the great advantage of using in the amperometric and conductometric methods only their advantages since the two electrochemical methods are complementary, also the dosing system of oxidazes is simple and accurate ensuring a good reproducibility of experimental data. By the -

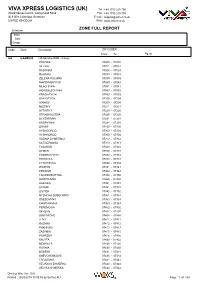

Viva Xpress Logistics (Uk)

VIVA XPRESS LOGISTICS (UK) Tel : +44 1753 210 700 World Xpress Centre, Galleymead Road Fax : +44 1753 210 709 SL3 0EN Colnbrook, Berkshire E-mail : [email protected] UNITED KINGDOM Web : www.vxlnet.co.uk Selection ZONE FULL REPORT Filter : Sort : Group : Code Zone Description ZIP CODES From To Agent UA UAAOD00 UA-Ukraine AOD - 4 days POLISKE 07000 - 07004 VILCHA 07011 - 07012 RADYNKA 07024 - 07024 RAHIVKA 07033 - 07033 ZELENA POLIANA 07035 - 07035 MAKSYMOVYCHI 07040 - 07040 MLACHIVKA 07041 - 07041 HORODESCHYNA 07053 - 07053 KRASIATYCHI 07053 - 07053 SLAVUTYCH 07100 - 07199 IVANKIV 07200 - 07204 MUSIIKY 07211 - 07211 DYTIATKY 07220 - 07220 STRAKHOLISSIA 07225 - 07225 OLYZARIVKA 07231 - 07231 KROPYVNIA 07234 - 07234 ORANE 07250 - 07250 VYSHGOROD 07300 - 07304 VYSHHOROD 07300 - 07304 RUDNIA DYMERSKA 07312 - 07312 KATIUZHANKA 07313 - 07313 TOLOKUN 07323 - 07323 DYMER 07330 - 07331 KOZAROVYCHI 07332 - 07332 HLIBOVKA 07333 - 07333 LYTVYNIVKA 07334 - 07334 ZHUKYN 07341 - 07341 PIRNOVE 07342 - 07342 TARASIVSCHYNA 07350 - 07350 HAVRYLIVKA 07350 - 07350 RAKIVKA 07351 - 07351 SYNIAK 07351 - 07351 LIUTIZH 07352 - 07352 NYZHCHA DUBECHNIA 07361 - 07361 OSESCHYNA 07363 - 07363 KHOTIANIVKA 07363 - 07363 PEREMOGA 07402 - 07402 SKYBYN 07407 - 07407 DIMYTROVE 07408 - 07408 LITKY 07411 - 07411 ROZHNY 07412 - 07412 PUKHIVKA 07413 - 07413 ZAZYMIA 07415 - 07415 POHREBY 07416 - 07416 KALYTA 07420 - 07422 MOKRETS 07425 - 07425 RUDNIA 07430 - 07430 BOBRYK 07431 - 07431 SHEVCHENKOVE 07434 - 07434 TARASIVKA 07441 - 07441 VELIKAYA DYMERKA 07442 - 07442 VELYKA -

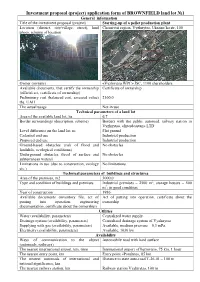

Investment Proposal (Project) Application Form of BROWNFIЕLD Land

Investment proposal (project) application form of BROWNFIЕLD land lot №1 General information Title of the investment proposal (project) Starting-up of a pellet production plant Location (district, city/village, street), land Chernivtsi region, Vyzhnytsa, Ukrains’ka str, 100 photo, scheme of location Owner (owners) «Vyzhnytsa WPC» JSC, 1100 shareholders Available documents, that certify the ownership Certificate of ownership (official act, certificate of ownership) Preliminary cost (balanced cost, assessed value) 2160,0 ths. UAH The actual usage Not in use Technical parameters of a land lot Area of the available land lot, ha 6,7 Border surroundings (description, scheme) Borders with the public autoroad, railway station in Vyzhnytsa, «Interdosstan» LTD Level difference on the land lot, m Flat ground Cadastral end use Industrial production Proposed end use Industrial production Ground-based obstacles (risk of flood and No obstacles landslide, ecological conditions) Underground obstacles (level of surface and No obstacles subterranean waters) Limitations in use (due to construction, ecology No limitations etc.) Technical parameters of buildings and structures Area of the premises, m2 3000,0 Type and condition of buildings and premises Industrial premises – 2500 m2, storage houses – 500 m2; in good condition Year of construction 1986 Available documents (inventory file, act of Act of putting into operation, certificate about the putting into operation, engineering ownership documentation, certificate about the ownership) Utilities Water (availability, -

Of the Public Purchasing Announcernº4(78) January 24, 2012

Bulletin ISSN: 2078–5178 of the public purchasing AnnouncerNº4(78) January 24, 2012 Announcements of conducting procurement procedures � � � � � � � � � 2 Announcements of procurement procedures results � � � � � � � � � � � � 70 Urgently for publication � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 124 Bulletin No�4(78) January 24, 2012 Annoucements of conducting 01500 Subsidiary Company “Naftogazservice”, procurement procedures NJSC “Naftogaz Ukrainy” 2 Lunacharskoho St., 02002 Kyiv tel.: (067) 444–69–72; 01498 Subsidiary Company “Naftogazservice”, tel./fax: (044) 531–12–57; NJSC “Naftogaz Ukrainy” e–mail: [email protected] 2 Lunacharskoho St., 02002 Kyiv Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: tel.: (067) 444–69–72; www.tender.me.gov.ua tel./fax: (044) 531–12–57; Procurement subject: code 50.30.2 – services in retail trade of parts e–mail: [email protected] and equipment for cars, 2 lots Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: Supply/execution: at the customer’s address; during 2012 www.tender.me.gov.ua Procurement procedure: open tender Procurement subject: code 50.20.1 – services in maintenance and repair Obtaining of competitive bidding documents: at the customer’s address, reception of passenger cars, 6 lots room Supply/execution: Kyiv and Kyiv Oblast, during 2012 Submission: at the customer’s address, reception room Procurement procedure: open tender 20.12.2011 09:30 Obtaining of competitive bidding documents: at the customer’s -

«Made in Bukovyna»

ELECTRONIC GUIDE OF ENTREPRENEURSHIP ACTIVITY IN CHERNIVTSI REGION «MADE IN BUKOVYNA» 2018 Contents Electronics and machine building………………………………………………………..5 «ARTON» private enterprise……………………………………………………………………………….6 JSC «SKB Electronmash»…………………………………………………………………………………..7 «Sokyrianskyi Mashynobudivnyi Zavod» ALC…………………………………………………………….8 «Mashzavod» Ltd…………………………………………………………………………………………...9 Research and Production Company (RPC) «Тensor»……………………………………………………...10 «SE Bordnetze-Ukraine» LLC (Chernivtsi region)………………………………………………….…….11 «Automotive Electric Ukraine» LLC (Chernivtsi region)…………………………………………………12 «Linhokomservis» LLC…………………………………………………………………………………...13 Institute of Thermoelectricity National Academy of Sciences and Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine…………………………………………………………………………………………………….14 Wood and forestry…………………………………………………………………….....15 Private enterprise «Kovali»………………………………………………………………………………..16 Public company «Vyzhnytsia dok»………………………………………………………………………..17 LTD «Pelet-GroupEko»…………………………………………………………………………………...18 State enterprise «Putyla forestry»………………………………………………………………………….19 State enterprise «Carpathians specialized forestry»……………………………………………………....20 Private enterprise «Lego»………………………………………………………………………………….21 «Impeks-service» LTD…………………………………………………………………………………….22 State enterprise «Sokyrianske Lisove Hospodarstvo»……………………………………………………..23 State enterprise «Storozhynets forestry»…………………………………………………………………..24 «BKM-WOOD» LLC……………………………………………………………………………………..25 State enterprise «Khotynske Lisove Hospodarstvo»………………………………………………………26 -

Management Report 2019 Supervisory Board Chairman Address 2

MANAGEMENT REPORT 2019 SUPERVISORY BOARD CHAIRMAN ADDRESS 2 CEO ADDRESS 4 1 ABOUT UKRHYDROENERGO 6 Our mission and values 8 Role of Ukrhydroenergo in the Ukrainian Energy Market 10 Highlights 2019 14 2 UKRHYDROENERGO DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY 20 Ukrhydroenergo Development Strategy 22 Key Operating Results 28 Investment Activities 36 Development and Innovations of HPPs and PSPs as objects 48 3 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 58 Corporate Governance System 60 Ukrhydroenergo’s Organisational Structure 66 Anti-Corruption Programme 86 Risk Management 88 4 SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL RESPONSIBILITY 92 Social Policy of the Company 94 Safe Working Conditions 108 Environmental Policy of the Company 112 Energy Efficiency and Energy Saving 124 5 ANNEXES 128 About the Report 130 Corporate social responsibility strategy 134 SUPERVISORY BOARD CHAIRMAN ADDRESS Since the establishment of its of the Company’s fixed assets) and Supervisory Board, Ukrhydroenergo raising foreign investments. That has been operating in a new is exactly why the sustainable and corporate governance system, which predictable development of the has a strong positive impact on the Company, capacity building, stable development of the Company and economic and financial position, and the national economy and is key to adherence to modern standards of the effective cooperation with our good standing are so crucial. partners and investor. Over this short term, the Supervisory Alongside other corporatised Board has already taken many businesses, our Company has important steps for Ukrhydroenergo’s embarked on a path of a prospective development in the new corporate sustainable development. Today, governance system. We keep on Ukrhydroenergo is a modern analysing the Company’s ability to business with a developed corporate meet its objectives and risks it may governance system in place that face, such as the dividend payout, balances the interests of the implementation of investment Company and its shareholder, programmes, etc. -

Announces a Competitive Selection of Consultants Provid

The International Charitable Foundation “Alliance for Public Health” Announces a competitive selection of consultants providing services of organization and conduction of the exploratory and qualitative research of programs, projects and services in the field of HIV prevention and harm reduction targeting adolescents who have experience of using drugs (AUD) and their sexual partners. The competition is conducted in the framework of the project “Underage, overlooked: Improving access to integrated HIV services for adolescents most at risk in Ukraine” (joint project of the International Charitable Foundation “AIDS Foundation East-West” (AFEW-Ukraine) and the International Charitable Foundation “Alliance for Public Health”, hereinafter – the Project) on work with adolescents, which is supported by Expertise France 5% Initiative. The International Charitable Foundation “Alliance for Public Health” (Alliance) is a leading professional organization, which in cooperation with key non-governmental organizations, the Ministry of Health and other government bodies is fighting a number of epidemics, including HIV/AIDS and TB in Ukraine, manages preventive programs and provides high-quality technical support and financial resources to local organizations. All these efforts are aimed at the achievement of the universal access to comprehensive services on HIV/AIDS in Ukraine and an effective response to the epidemic at the community level, based on the achieved results and best practices. As an independent legal entity registered in Ukraine since 2003 and after gaining the managerial autonomy since January 2009, the Alliance shares the same values and remains a member of the global partnership of the International Alliance on HIV/AIDS (International Charitable Organization, which unites 30 organizations from different countries, with a Secretariat in Brighton, the United Kingdom). -

GEOLEV2 Label Updated October 2020

Updated October 2020 GEOLEV2 Label 32002001 City of Buenos Aires [Department: Argentina] 32006001 La Plata [Department: Argentina] 32006002 General Pueyrredón [Department: Argentina] 32006003 Pilar [Department: Argentina] 32006004 Bahía Blanca [Department: Argentina] 32006005 Escobar [Department: Argentina] 32006006 San Nicolás [Department: Argentina] 32006007 Tandil [Department: Argentina] 32006008 Zárate [Department: Argentina] 32006009 Olavarría [Department: Argentina] 32006010 Pergamino [Department: Argentina] 32006011 Luján [Department: Argentina] 32006012 Campana [Department: Argentina] 32006013 Necochea [Department: Argentina] 32006014 Junín [Department: Argentina] 32006015 Berisso [Department: Argentina] 32006016 General Rodríguez [Department: Argentina] 32006017 Presidente Perón, San Vicente [Department: Argentina] 32006018 General Lavalle, La Costa [Department: Argentina] 32006019 Azul [Department: Argentina] 32006020 Chivilcoy [Department: Argentina] 32006021 Mercedes [Department: Argentina] 32006022 Balcarce, Lobería [Department: Argentina] 32006023 Coronel de Marine L. Rosales [Department: Argentina] 32006024 General Viamonte, Lincoln [Department: Argentina] 32006025 Chascomus, Magdalena, Punta Indio [Department: Argentina] 32006026 Alberti, Roque Pérez, 25 de Mayo [Department: Argentina] 32006027 San Pedro [Department: Argentina] 32006028 Tres Arroyos [Department: Argentina] 32006029 Ensenada [Department: Argentina] 32006030 Bolívar, General Alvear, Tapalqué [Department: Argentina] 32006031 Cañuelas [Department: Argentina] -

Industrial Parks in Ukraine

Industrial parks in Ukraine 2017 Industrial parks in Ukraine main concepts According to the Law of Ukraine “On Industrial Parks” Industrial Park (IP) is a land plot that is equipped with proper infrastructure where participants of IP can engage in such economic activities as Process Industry Research and Development (R&D) Information and Telecommunication IP land should belong to the Industrial Lands IP may be located on one or several adjacent land parcels IP square could be from 15 to 700 ha IP is created for a period of at least 30 years IP land parcels of state and local public property may be sold to IP management company and IP participants at the time of IP inclusion into the Register should be no integral property complex that allows to producing goods Industrial parks in Ukraine IP subjects Initiator of IP creation: the state power bodies on state lands the local authorities on communal lands legal or physical persons – owners of private lands legal or physical persons – lessees of state, communal and private lands IP Management Company should be a legal person irrespective of its organizational form created according to Ukraine Legislation IP participants should be economic entities of any form of ownership, registered at the administrative territory of Ukraine where the IP is created Industrial parks in Ukraine benefits to the parties concerned Benefits for IP Participants – minimizing material, financial, human and time resources costs required for initiating economic activities, access to services related to the provision -

Udc 911.3 Doi: 10.26565/2076-1333-2020-29-09

2020 Часопис соціально-економічної географії випуск 29 UDC 911.3 DOI: 10.26565/2076-1333-2020-29-09 Yuriі Bilous PhD Student of the Department of Geography of Ukraine and Regional Studies e-mail: [email protected], ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8539-275X Yuriy Fedkovych Chernivtsi National University, Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky street 2, building 4, Chernivtsi, 58012, Ukraine SOCIAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL FEATURES OF THE FORMATION OF THE INTELLECTUAL POTENTIAL OF CHERNIVTSI OBLAST The article studies the peculiarities of the formation of intellectual potential of Chernivtsi oblast by analyzing its components, and also analyzes the participation of students in student competitions in subjects and in the competition-defense of research works of students of the Small Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, as well as their results. The analysis of gender peculiarities of students‘ par- ticipation in the researched competitions is carried out, and also the geographical factors influencing formation of intellectual poten- tial are considered. In 2019, there were 372 preschool educational institutions, 403 general secondary education institutions, 16 vocational educa- tion institutions and 16 higher education institutions in Chernivtsi oblast, which provided relevant educational services and formed the intellectual potential of the region. In Chernivtsi oblast in the 2019-2020 academic year, 1,814 students took part in the III stage of student academic competitions. The largest number of participants was observed at the academic competition in geography, Ukrainian language and literature, history and biology. In total, 845 participants took top places. The best results were shown by students of Chernivtsi, Storozhynets AH, Novoselytsia AH and students of Kelmentsi rayon.