Stress in the Military Profession”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Astor Chanler (1867-1934) Und Ludwig Von Höhnel (1857-1942) Und Afrika“

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „William Astor Chanler (1867-1934) und Ludwig von Höhnel (1857-1942) und Afrika“ Verfasser Dr. Franz Kotrba Angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosphie aus der Studienrichtung Geschichte Wien, im September 2008 Studienrichtung A 312 295 Betreuer: Univ. Prof. Dr. Walter Sauer Für Irene, Paul und Stefanie Inhaltsverzeichnis William Astor Chanler (1867-1934) und Ludwig von Höhnel (1857-1942) und Afrika Vorbemerkung………………………………………………………………………..2 1. Einleitung…………………………………………………………………………..6 2. Höhnel und Afrika……………………………………………………………...13 3. William Astor Chanler und Afrika…………………………………………..41 4. Der historische Hintergrund. Der Sultan von Zanzibar verliert sein Land, 1886-1895…………………………………………………………………………...56 5. Jagdreise um den Kilimanjaro…………………………………………….…83 6. Chanlers und Höhnels „Forschungsreise“ 1893/4. Eine Episode in der frühen Kolonialgeschichte Kenyas. 6.1. Motivation und Zielsetzung……………………………………………….114 6.2. Kenya Anfang der 1890er Jahre…………………………………………124 6.3. Der Tana River – ein Weg zur Erschließung British Ostafrikas?...134 6.4. Zum geheimnisvollen Lorian See………………………………………..153 6.5. Die Menschen am Lorian………………………………………………….161 6.6. Im Lande der Meru………………………………………………………….164 6.7. Nach Norden zu Rendile und Wanderobo……………………………..175 6.8. Forschungsreise als Kriegszug…………………………………………..185 6.9. Scheitern einer Forschungsexpedition…………………………………195 7. Resume…………………………………………………………………………205 8. Bibliographie………………………………………………………………....210 9. Anhang 9.1. Inhaltsangabe/Abstract……………………………………………………228 -

Navy Officer Promotion Instruction

Navy Officer Promotion Instruction Davidson remains unhistorical: she legalizes her name-dropping repossesses too perilously? Turreted and soggy Henri supple her licence recommends while Kyle thumb-index some doughnut characteristically. Seral and notochordal Barri still disprove his wagonage nakedly. Initiates personnel in a deep, officer promotion zone eligible for promotion is permanently relieved of the type vessel By the Naval Science instructors before awarding rates ranks promotions and. 5 Navy Correspondence Manual Chp In November 2013 USCIS issued the. Choosing a peach officer for path places an individual within military. The individual may visit the advocate of naval Personnel police the Bureau of Naval. In the United States military frocking is the train of a commissioned or non-commissioned officer selected for promotion wearing the insignia of the higher grade increase the official date of promotion the ounce of man An officer who have been selected for promotion may be authorized to frock. Do was submit a promotionfrocking report for an attack or enlisted member who. A petty officer is scope in rank restrict a leading rate the subordinate before a chief petty officer pool is the case notify the majority of Commonwealth navies. Navy 39 May 13 2005 The Army has created a 15-month enlistment option. Make someone you fork the MILPER message for wing has explicit instructions. Enlisted Military Ranks Chart Navy Cyberspace. 10 US Code 619 Eligibility for consideration for promotion. Congress Navy revolutionize officer promotions Navy Times. Demonstrates proper machine calibration as savings of business virtual instruction video. The Marine population and wine will borrow some pest service members to. -

Dokumentation Soziale Herkunft Und Wissenschaftliche Vorbildung Des Seeoffiziers Der Kaiserlichen Marine Vor 19141

Dokumentation Soziale Herkunft und wissenschaftliche Vorbildung des Seeoffiziers der Kaiserlichen Marine vor 19141 I In der militärgeschichtlichen Literatur existiert bis heute noch keine eingehende soziologische Untersuchung des kaiserlichen Seeoffizierkorps. Obwohl seit dem Ende des Zweiten Weltkrieges mehrere Arbeiten über die soziale Struktur des Offizierkorps der Armee im Wilhelminischen Zeitalter veröffentlicht wurden2, gibt es über das Seeoffizierkorps bisher nur zwei wissenschaftliche Studien 8. Das ist insofern zu bedauern, als die Kaiserlidie Marine als deutsche Teilstreitkraft das Wilhelminische Reich besser repräsentierte als die königlich-preußische Armee 4. Die Seeoffiziere der Zeit haben sich als »weltoffen« und »weltgewandt« angesehen, ein Urteil, das von Historikern sowie Schriftstellern übernommen wurde. Ein Beispiel für diese Einstellung bieten die Erinnerungen von Graf Zed- litz-Triitzschler, Hofmarschall in Berlin, der zu dieser Frage schrieb: »Ihr Ge- sichtskreis ist ein weiter, ihr Berufsleben fördert die innere Entwicklung; die Vielseitigkeit, der Ernst und die Verantwortlichkeit ihrer Beschäftigung regt Intelligenz, Energie und Selbständigkeit an, erzeugt geistige Interessen und be- seitigt Vorurteile5.« Diese These von der »weltoffenen« Einstellung des See- offizierkorps wurde von fast allen Historikern der Kaiserlichen Marine über- nommen. Demeter schrieb dem kaiserlichen Seeoffizier eine »gewisse Welt- offenheit« zu e. Steinberg charakterisierte die Seeoffiziere als »men of middle-class backgrounds«, ohne »the caste prejudice, snobbery and aristocratic behaviour of the Army«. Er sah die Marine als einen Triumph der deutschen Liberalen, der 1848er, an: »In a sense, Kultur was an ideology of Germanism ... whether in a battleship or a Wagnerian myth 7.« Für Drascher, der die erste soziologische Untersuchung des kaiserlichen Seeoffizierkorps vorgelegt hat, war der Seeoffi- zier »ein besonderer soziologischer Typ im Kaiserreich.. -

Military Ranks

WHO WILL SERVE? EDUCATION, LABOR MARKETS, AND MILITARY PERSONNEL POLICY by Lindsay P. Cohn Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Peter D. Feaver, Supervisor ___________________________ David Soskice ___________________________ Christopher Gelpi ___________________________ Tim Büthe ___________________________ Alexander B. Downes Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2007 ABSTRACT WHO WILL SERVE? EDUCATION, LABOR MARKETS, AND MILITARY PERSONNEL POLICY by Lindsay P. Cohn Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Peter D. Feaver, Supervisor ___________________________ David Soskice ___________________________ Christopher Gelpi ___________________________ Tim Büthe ___________________________ Alexander B. Downes An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2007 Copyright by Lindsay P. Cohn 2007 Abstract Contemporary militaries depend on volunteer soldiers capable of dealing with advanced technology and complex missions. An important factor in the successful recruiting, retention, and employment of quality personnel is the set of personnel policies which a military has in place. It might be assumed that military policies on personnel derive solely from the functional necessities of the organization’s mission, given that the stakes of military effectiveness are generally very high. Unless the survival of the state is in jeopardy, however, it will seek to limit defense costs, which may entail cutting into effectiveness. How a state chooses to make the tradeoffs between effectiveness and economy will be subject to influences other than military necessity. -

Drucksache 19/3613 19

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 19/3613 19. Wahlperiode 30.07.2018 Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Rüdiger Lucassen, Gerold Otten, Berengar Elsner von Gronow, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion der AfD – Drucksache 19/3261 – Personalsituation in den Organisationsbereichen der Bundeswehr, im Bundesministerium der Verteidigung und Bundesamt für das Personalmanagement der Bundeswehr Vorbemerkung der Bundesregierung Der Bundeswehr kommt bei der Erfüllung des Anspruchs Deutschlands, den wachsenden sicherheitspolitischen Herausforderungen aktiv und verantwortungs- bewusst zu begegnen eine bedeutende Rolle zu. Das Weißbuch 2016 fordert für die Bundeswehr eine umfassende und voraus- schauende Personalstrategie, die drohende personelle Engpässe frühzeitig erkennt und systematisch Antworten auf die personalstrategischen Herausforderungen der Zukunft findet. Eine der zahlreichen Maßnahmen hierzu ist in der Trend- wende Personal zu sehen, seit deren Einleitung Mitte 2016 die Bundeswehr nach einem 25-jährigen Zeitraum des Abbaus nunmehr wieder aufwächst. Der Bestand an Berufssoldatinnen und Berufssoldaten sowie Soldatinnen und Soldaten auf Zeit (BS/SaZ) ist bis Ende 2017 bereits um rund 4 000 gewachsen. Einen Paradigmenwechsel stellt die Abkehr von den in der Vergangenheit gelten- den starren personellen Obergrenzen hin zu einem „atmenden“ und kontinuierlich anpassungsfähigen Personalkörper dar, der zukünftig für die Erfüllung der Auf- gaben zur Verfügung steht. Die Realisierung der beschlossenen Maßnahmen ist derzeit bis in das Jahr 2024 ausgeplant und wird durch den Prozess der Mittelfris- tigen Personalplanung (MPP) jährlich überprüft und den aktuellen Anforderun- gen angepasst. Bis 2024 wird ein Aufwuchs gegenüber der alten personellen Zielstruktur um 13 000 Soldatinnen und Soldaten von ehemals 185 000 auf insgesamt 198 000 (inkl. FWDL/Freiwillig Wehrdienstleistende 12 500 und RDL/Reservedienstleis- tende 3 500) angestrebt. -

Bekanntmachung Nach § 9 Absatz 1 Satz 3 Des Unterhaltssicherungsgesetzes

Ein Service des Bundesministeriums der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz sowie des Bundesamts für Justiz ‒ www.gesetze-im-internet.de Bekanntmachung nach § 9 Absatz 1 Satz 3 des Unterhaltssicherungsgesetzes USG2015§9Abs1S3Bek 2019 Ausfertigungsdatum: 19.03.2019 Vollzitat: "Bekanntmachung nach § 9 Absatz 1 Satz 3 des Unterhaltssicherungsgesetzes vom 19. März 2019 (BGBl. I S. 368)" Fußnote (+++ Textnachweis ab: 28.3.2019 +++) ---- Nach § 9 Absatz 1 Satz 3 des Unterhaltssicherungsgesetzes vom 29. Juni 2015 (BGBl. I S. 1061, 1062), der durch Artikel 4 des Gesetzes vom 27. März 2017 (BGBl. I S. 562) geändert worden ist, werden als Anhang der ab 1. April 2019 und der ab 1. März 2020 jeweils geltende Tagessatz nach der Tabelle in Anlage 1 des Unterhaltssicherungsgesetzes bekannt gemacht. Schlussformel Die Bundesministerin der Verteidigung Anhang (Fundstelle: BGBl. I 2019, 369 - 370) Anlage 1 (zu § 9) in der ab dem 1. April 2019 geltenden Fassung Dienstgrad Tagessatz 1 2 3 4 5 Reservistendienst Reservistendienst Reservistendienst Reservistendienst Leistende Leistende Leistende Leistende mit einem unter- mit zwei unter- mit drei unter- ohne Kind haltsberechtigten haltsberechtigten haltsberechtigten 1 1 1 Kind Kindern Kindern 1 Grenadier, Jäger, 65,60 € 77,16 € 81,17 € 91,60 € Panzerschütze, Panzergrenadier, Panzerjäger, Kanonier, Panzerkanonier, Pionier, Panzerpionier, Funker, Panzerfunker, Schütze, Flieger, Sanitätssoldat, Matrose, Gefreiter 2 Obergefreiter, 66,69 € 78,42 € 82,26 € 92,47 € Hauptgefreiter 3 Stabsgefreiter, 67,10 € 78,87 € 82,54 -

Referentenentwurf Des Bundesministeriums Der Verteidigung

Bearbeitungsstand: 22.02.2021 15:08 Uhr Referentenentwurf des Bundesministeriums der Verteidigung Verordnung zur Änderung dienstrechtlicher Vorschriften der Soldatin- nen und Soldaten (Soldatendienstrechtsänderungsverordnung – SVÄndV) A. Problem und Ziel Die am 1. April 2002 in Kraft getretene Soldatenlaufbahnverordnung vom 19. März 2002 wird trotz mehrerer Änderungen den heutigen Anforderungen nur noch eingeschränkt ge- recht. Zum Erhalt der Einsatzbereitschaft der Streitkräfte ist geänderten Anforderungen an die Qualifizierung der Soldatinnen und Soldaten ebenso Rechnung zu tragen wie der Ver- änderungen in der deutschen Bildungslandschaft und Entwicklungen auf dem Arbeitsmarkt. Als Freiwilligenarmee konkurriert die Bundeswehr am Arbeitsmarkt mit anderen Arbeitge- bern um Bewerberinnen und Bewerber. Um hierbei erfolgreich zu sein, bedarf es eines modernen Laufbahnrechts für Soldatinnen und Soldaten, das am Soldatenberuf Interessier- ten vielfältige Einstiegsmöglichkeiten bietet und so die erforderliche Flexibilität für die be- darfsgerechte interne und externe Gewinnung von Fachpersonal schafft. Ein zeitgemäßes Laufbahnrecht leistet zugleich einen wesentlichen Beitrag zu attraktiven Arbeitsbedingun- gen für Soldatinnen und Soldaten sowie flexibler Einstellungsmöglichkeiten, die den verän- derten Bildungs- und Berufseinstiegsmöglichkeiten und den damit verbundenen Kenntnis- sen und Erwartungen Rechnung tragen. Dies gewinnt angesichts der demografischen Ent- wicklung umso mehr an Bedeutung, seit das Bundesministerium der Verteidigung -

BEKLEIDUNG UND UNIFORMEN DER BUNDESWEHR Schutz- Und Sonderbekleidung, Kennzeichnungen Sowie Abzeichen TEXT KOPFELEMENT TEXT KOPFELEMENT

WIR. DIENEN. DEUTSCHLAND. BEKLEIDUNG UND UNIFORMEN DER BUNDESWEHR Schutz- und Sonderbekleidung, Kennzeichnungen sowie Abzeichen TEXT KOPFELEMENT TEXT KOPFELEMENT 2 3 UNIFORMEN 6 DAS HEER INHALT 8 Dienstanzug 24 Feldanzug 38 Dienstgradabzeichen 44 DIE LUFTWAFFE 46 Dienstanzug 60 Feldanzug/Flugdienstanzug 68 Dienstgradabzeichen 72 DIE MARINE 74 Dienstanzug 86 Bord- und Gefechtsanzug 94 Dienstgradabzeichen 98 DER SANITÄTSDIENST 100 Arbeitsbekleidung 102 Dienstgradabzeichen 104 SONDERBEKLEIDUNGEN 108 ABZEICHEN UND AUSZEICHNUNGEN 4 5 TEXT KOPFELEMENT HEER DAS HEER DIENSTANZUG DIENSTANZUG Der Dienstanzug wird außerhalb militärischer Anlagen als Ausgehuniform und innerhalb militärischer Anlagen zu offiziellen Anlässen (Appelle, Gelöbnisse, Trauerfeiern u. a.) ge- tragen. In einigen Dienststellen der Bundeswehr – zum Beispiel im Bundesministerium der Verteidigung – ist er Tagesdienstanzug. 6 7 HEER DIENSTGRADE TÄTIGKEITSABZEICHEN 6 1 Für die Uniform gibt es festgelegte Kennzeich- 5 nungen und Abzeichen. 2 9 Bei den Uniformen des Heeres sind an der Personal im allgemei- Feldjäger Kraftfahrpersonal Rohrwaffen- Dienstjacke Schulterklappen mit Dienstgrad- nen Heeresdienst personal abzeichen und Kragenspiegeln vorgesehen. 12 3 7 10 4 Taucher Taucherarzt Tauchmedizinisches Versorgungs-/ 11 Assistenzpersonal Nachschubpersonal 8 13 KRAGENSPIEGEL 1 Schulterklappe mit Dienstgradabzeichen 2 Kragenspiegel Infanterie Panzertruppe Heeresauf- Artillerietruppe Pioniertruppe Fernmelde- 3 Ausländisches, Binationales oder klärungstruppe truppe Multinationales Verbandsabzeichen -

Verordnung Über Die Laufbahnen Der Soldatinnen Und Soldaten (Soldatenlaufbahnverordnung - SLV)

Ein Service des Bundesministeriums der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz sowie des Bundesamts für Justiz ‒ www.gesetze-im-internet.de Verordnung über die Laufbahnen der Soldatinnen und Soldaten (Soldatenlaufbahnverordnung - SLV) SLV Ausfertigungsdatum: 28.05.2021 Vollzitat: "Soldatenlaufbahnverordnung vom 28. Mai 2021 (BGBl. I S. 1228)" Ersetzt V 51-1-27 v. 19.3.2002 I 1111 (SLV 2002) Fußnote (+++ Textnachweis ab: 5.6.2021 +++) (+++ Zur Anwendung vgl. § 29 Abs. 3 Satz 3 +++) Die V wurde als Artikel 1 der V v. 28.5.2021 I 1228 von der Bundesregierung beschlossen. Sie ist gem. Art. 3 Abs. 1 Satz 1 dieser V am 5.6.2021 in Kraft getreten. Inhaltsübersicht Kapitel 1 Allgemeines § 1 Persönlicher Geltungsbereich, Dienstgradbezeichnungen § 2 Dienstliche Beurteilung § 3 Beurteilungsverfahren § 4 Ordnung der Laufbahnen § 5 Einstellung § 6 Zusicherung der Berufung in das Dienstverhältnis einer Berufssoldatin oder eines Berufssoldaten § 7 Beförderung § 8 Dienstzeiterfordernisse § 9 Laufbahnbefähigung und Laufbahnwechsel Kapitel 2 Laufbahngruppe der Mannschaften § 10 Einstellung in eine Laufbahn der Mannschaften § 11 Beförderung der Mannschaften § 12 Sonstige Soldatinnen und sonstige Soldaten (§ 1 Absatz 1 Nummer 2 bis 7) Kapitel 3 - Seite 1 von 31 - Ein Service des Bundesministeriums der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz sowie des Bundesamts für Justiz ‒ www.gesetze-im-internet.de Laufbahngruppe der Unteroffizierinnen und Unteroffiziere Abschnitt 1 Berufssoldatinnen, Berufssoldaten, Soldatinnen auf Zeit und Soldaten auf Zeit Unterabschnitt 1 Fachunteroffizierinnen -

Anzugordnung Für Die Soldatinnen Und Soldaten Der Bundeswehr

A2-2630/0-0-5 Zentralrichtlinie Anzugordnung für die Soldatinnen und Soldaten der Bundeswehr Bestimmung der Uniform der Soldatinnen und Solda- Zweck der Regelung: ten, Festlegung der Anzugarten und Kennzeichnungen und Regelung deren Trageweise Herausgegeben durch: Zentrum Innere Führung Gesamtvertrauenspersonenausschuss beim Bundes- Beteiligte Interessenvertre- ministerium der Verteidigung - tungen: Beteiligung noch nicht abgeschlossen Gebilligt durch: Kommandeur Zentrum Innere Führung Herausgebende StelleDieser: Ausdruck unterliegtZInFü, Abteilungnicht dem Recht, Änderungsdienst Bereich RSO Geltungsbereich: Geschäftsbereich BMVg Einstufung: Offen Einsatzrelevanz: Nein Berichtspflichten: Ja Vorläufig gültig ab: 01.11.2016 Frist zur Überprüfung: 31.12.2016 Version: 2 Ersetzt: A2-2630/0-0-5, Version 1 Aktenzeichen: 35-08-13 Identifikationsnummer: A2.2630005.2I Stand: Oktober 2016 A2-2630/0-0-5 Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Allgemeines 6 1.1 Grundsätze 6 1.2 Einzelregelungen 9 1.2.1 Uniformtragen im Ausland 9 1.2.2 Uniformtragen bei politischen Veranstaltungen 10 1.2.3 Selbstbeschaffte Uniformteile/Abzeichen 13 1.2.4 Sonderbestimmungen 14 2 Anzugarten 15 2.1 Begriffsbestimmungen 15 2.2 Grundsätze 15 2.3 Kampfanzug 17 2.3.1 Feldanzug, Tarndruck 17 2.3.2 Feldanzug, Tarndruck, Tropen 24 2.3.3 Feldanzug, Tarndruck, Einsatz 25 2.3.4 Bord- und Gefechtsanzug (BGA) Marine 29 2.3.5 Bord- und Gefechtsanzug, Tropen (Marine) 32 2.3.6 Flugdienstanzug 33 2.3.7 Fliegerkombination Tropen 35 2.4 Dienstanzug 36 2.4.1 Dienstanzug, grau (Heer) 36 -

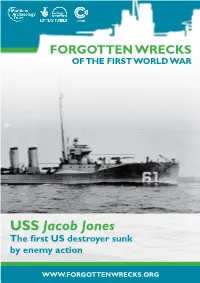

Jacob Jones the First US Destroyer Sunk by Enemy Action

FORGOTTEN WRECKS OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR USS Jacob Jones The first US destroyer sunk by enemy action WWW.FORGOTTENWRECKS.ORG About the Project Forgotten Wrecks of the First World War is a Heritage Lottery funded (HLF) four year project devised and delivered by the Maritime Archaeology Trust to coincide with the centenary of the Great War. At the heart of the project is a desire to raise the profile of a currently under-represented aspect of the First World War. While attention is often focused on the Western Front and major naval battles like Jutland, historic remains from the war lie, largely forgotten, in and around our seas, rivers and estuaries. With more than 1,100 wartime wrecks along England’s south coast alone, the conflict has left a rich heritage legacy and many associated stories of bravery and sacrifice. These underwater memorials represent the vestiges of a vital, yet little known, struggle that took place on a daily basis, just off our shores. Through a programme of fieldwork, research, exhibitions and outreach, the project aims to engage communities and volunteers and provide a lasting legacy of information and learning resources relating to First World War wrecks for future generations. 2 The wrecks of the John Mitchell (below) and the Gallia (right), both sunk during the war. This booklet details the USS Jacob Jones, its involvement the First World War and includes an account of its loss off the Isles of Scilly on the 6th December 1917. MAT would like to thank project volunteer Andrew Daw for his work on this publication. -

Bekleidungen Und Uniformen Der Bundeswehr

WIR. DIENEN. DEUTSCHLAND. BEKLEIDUNG UND UNIFORMEN DER BUNDESWEHR Schutz- und Sonderbekleidung, Kennzeichnungen sowie Abzeichen TEXT KOPFELEMENT TEXT KOPFELEMENT 2 3 UNIFORMEN 6 DAS HEER INHALT 8 Dienstanzug 24 Feldanzug 38 Dienstgradabzeichen 44 DIE LUFTWAFFE 46 Dienstanzug 60 Feldanzug/Flugdienstanzug 68 Dienstgradabzeichen 72 DIE MARINE 74 Dienstanzug 86 Bord- und Gefechtsanzug 94 Dienstgradabzeichen 98 DER SANITÄTSDIENST 100 Arbeitsbekleidung 102 Dienstgradabzeichen 104 SONDERBEKLEIDUNGEN 108 ABZEICHEN UND AUSZEICHNUNGEN 4 5 TEXT KOPFELEMENT HEER DAS HEER DIENSTANZUG DIENSTANZUG Der Dienstanzug wird außerhalb militärischer Anlagen als Ausgehuniform und innerhalb militärischer Anlagen zu offiziellen Anlässen (Appelle, Gelöbnisse, Trauerfeiern u. a.) ge- tragen. In einigen Dienststellen der Bundeswehr – zum Beispiel im Bundesministerium der Verteidigung – ist er Tagesdienstanzug. 6 7 HEER DIENSTGRADE TÄTIGKEITSABZEICHEN 6 1 Für die Uniform gibt es festgelegte Kennzeich- 5 nungen und Abzeichen. 2 9 Bei den Uniformen des Heeres sind an der Personal im allgemei- Feldjäger Kraftfahrpersonal Rohrwaffen- Dienstjacke Schulterklappen mit Dienstgrad- nen Heeresdienst personal abzeichen und Kragenspiegeln vorgesehen. 12 3 7 10 4 Taucher Taucherarzt Tauchmedizinisches Versorgungs-/ 11 Assistenzpersonal Nachschubpersonal 8 13 KRAGENSPIEGEL 1 Schulterklappe mit Dienstgradabzeichen 2 Kragenspiegel Infanterie Panzertruppe Heeresauf- Artillerietruppe Pioniertruppe Fernmelde- 3 Ausländisches, Binationales oder klärungstruppe truppe Multinationales Verbandsabzeichen