Case Study Report BRISTOL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victoria Street | Bristol | Bs1 6Hz One Prime Location Broadmead Cabot Circus

VICTORIA STREET | BRISTOL | BS1 6HZ ONE PRIME LOCATION BROADMEAD CABOT CIRCUS ONE HUNDRED VICTORIA STREET CASTLE PARK is located in an enviable location at the junction of Victoria Street and Temple Way, VICTORIA STREET | BRISTOL | BS1 6HZ just a short walk from Temple Meads railway station and a wide range of amenities. Cafes, bars and restaurants are all readily accessible, as are car parks and hotels. VICTORIA ST 5 MINUTES WALK FROM BRISTOL TEMPLE WAY TEMPLE MEADS RAILWAY STATION ADJACENT TO THE BRISTOL NOVOTEL VICTORIA STREET GLASS WHARF TEMPLE QUAY TEMPLE MEADS STATION TEMPLE WAY TEMPLE MEADS GLASS WHARF ONE HIGH PROFILE OFFICE BUILDING ONE HUNDRED VICTORIA STREET comprises a high specification office building over ground and five upper floors, together with secure basement parking. ACCOMMODATION LOBBY The accommodation benefits from a total of 9 car parking spaces LIFT 1 LIFT 2 THE FOURTH FLOOR PROVIDES situated within the basement together with cycle storage and FEMALE WC THE FOLLOWING SPECIFICATION: provides the following approximate net internal floor areas: MALE WC AREA SQ FT SQ M • FOUR PIPE FAN COIL AIR CONDITIONING Ground floor 4,481 416.3 V I C T O R I A S T R E E T FOURTH FLOOR • NEWLY CARPETED RAISED FLOORS Fourth floor 5,950 552.8 T E M P L E W A Y TOTAL 10,431 969.1 • SUSPENDED CEILINGS WITH LED LIGHTING • DOUBLE GLAZED WINDOWS • MANNED RECEPTION • TWO PASSENGER LIFTS • SECURE BASEMENT CAR PARKING AT 1:1,190 SQ FT • EPC RATING OF D (80) THE GROUND FLOOR IS TO BE REFURBISHED, SPECIFICATION TO BE CONFIRMED. -

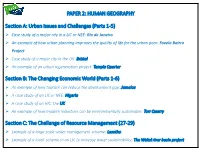

Urban Issues and Challenges

PAPER 2: HUMAN GEOGRAPHY Section A: Urban Issues and Challenges (Parts 1-5) Case study of a major city in a LIC or NEE: Rio de Janeiro An example of how urban planning improves the quality of life for the urban poor: Favela Bairro Project Case study of a major city in the UK: Bristol An example of an urban regeneration project: Temple Quarter Section B: The Changing Economic World (Parts 1-6) An example of how tourism can reduce the development gap: Jamaica A case study of an LIC or NEE: Nigeria A case study of an HIC: the UK An example of how modern industries can be environmentally sustainable: Torr Quarry Section C: The Challenge of Resource Management (27-29) Example of a large scale water management scheme: Lesotho Example of a local scheme in an LIC to increase water sustainability: The Wakel river basin project Section A: Urban Issues and Challenges (Parts 1-5) Case study of a major city in a LIC or NEE: Rio de Janeiro An example of how urban planning improves the quality of life for the urban poor: Favela Bairro Project Case study of a major city in the UK: Bristol An example of an urban regeneration project: Temple Quarter 2 Y10 – The Geography Knowledge – URBAN ISSUES AND CHALLENGES (part 1) 17 Urbanisation is….. The increase in people living in towns and cities More specifically….. In 1950 33% of the world’s population lived in urban areas, whereas in 2015 55% of the world’s population lived in urban areas. By 2050…. -

Bristol Arena Island Proposals, Temple Quarter, Bristol

TRANSPORT ASSESSMENT Bristol Arena Island Proposals, Temple Quarter, Bristol Prepared for Bristol City Council November 2015 1, The Square Temple Quay Bristol BS1 6DG Contents Section Page Acronyms and Abbreviations ................................................................................................................ vii Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.2 Report Purpose ........................................................................................................... 1-1 1.3 BCC Scoping Discussions .............................................................................................. 1-1 1.4 Arena Operator Discussions ......................................................................................... 1-2 1.5 Report Structure.......................................................................................................... 1-2 Transport Policy Review...................................................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 2-1 2.2 Local Policy .................................................................................................................. 2-1 2.2.1 The Development -

Bristol City Centre Retail Study: Stages 1 & 2

www.dtz.com Bristol City Centre Retail Study: Stages 1 & 2 Bristol City Council June 2013 DTZ, a UGL company One Curzon Street London W1J 5HD Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 2 Contextual Review ......................................................................................................................... 5 3 Retail and Leisure Functions of Bristol City Centre’s 7 Retail Areas ............................................ 14 4 Basis of the Retail Capacity Forecasts .......................................................................................... 31 5 Quantitative Capacity for New Retail Development ................................................................... 43 6 Qualitative Retail Needs Assessment .......................................................................................... 50 7 Retailer Demand Assessment ...................................................................................................... 74 8 Commercial Leisure Needs Assessment ...................................................................................... 78 9 Review of Potential Development Opportunities ........................................................................ 87 10 Review of Retail Area and Frontage Designations .................................................................... 104 11 Conclusions and Implications for Strategy .............................................................................. -

The History of Transport Systems in the UK

The history of transport systems in the UK Future of Mobility: Evidence Review Foresight, Government Office for Science The history of transport systems in the UK Professor Simon Gunn Centre for Urban History, University of Leicester December 2018 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr Aaron Andrews for his help with the research for this review, especially for creating the graphs, and Georgina Lockton for editing. The review has benefited from the input of an Advisory Group consisting of Professor Colin Divall (University of York); Professor Gordon Pirie (University of Cape Town); Professor Colin Pooley (Lancaster University); Professor Geoff Vigar (University of Newcastle). I thank them all for taking time to read the review at short notice and enabling me to draw on their specialist expertise. Any errors remaining are, of course, mine. This review has been commissioned as part of the UK government’s Foresight Future of Mobility project. The views expressed are those of the author and do not represent those of any government or organisation. This document is not a statement of government policy. This report has an information cut-off date of February 2018. The history of transport systems in the UK Executive summary The purpose of this review is to summarise the major changes affecting transport systems in the UK over the last 100 years. It is designed to enable the Foresight team to bring relevant historical knowledge to bear on the future of transport and mobility. The review analyses four aspects of transport and mobility across the twentieth century. The first section identifies significant points of change in the main transport modes. -

Prostitution in Bristol and Nantes, 1750-1815: a Comparative Study

Prostitution in Bristol and Nantes, 1750-1815: A comparative study Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy at the University of Leicester Marion Pluskota Centre for Urban History University of Leicester July 2011 Abstract This thesis is centred on prostitution in Nantes and Bristol, two port cities in France and England, between 1750 and 1815. The objectives of this research are fourfold: first, to understand the socio-economic characteristics of prostitution in these two port cities. Secondly, it aims to identify the similarities and the differences between Nantes and Bristol in the treatment of prostitution and in the evolution of mentalités by highlighting the local responses to prostitution. The third objective is to analyse the network of prostitution, in other words the relations prostitutes had with their family, the tenants of public houses, the lodging-keepers and the agents of the law to demonstrate if the women were living in a state of dependency. Finally, the geography of prostitution and its evolution between 1750 and 1815 is studied and put into perspective with the socio- economic context of the different districts to explain the spatial distribution of prostitutes in these two port cities. The methodology used relies on a comparative approach based on a vast corpus of archives, which notably includes judicial archives and newspapers. Qualitative and quantitative research allows the construction of relational databases, which highlight similar patterns of prostitution in both cities. When data is missing and a strict comparison between Nantes and Bristol is made impossible, extrapolations and comparisons with studies on different cities are used to draw subsequent conclusions. -

The Development of the Railway Network in Britain 1825-19111 Leigh Shaw-Taylor and Xuesheng You 1

The development of the railway network in Britain 1825-19111 Leigh Shaw-Taylor and Xuesheng You 1. Introduction This chapter describes the development of the British railway network during the nineteenth century and indicates some of its effects. It is intended to be a general introduction to the subject and takes advantage of new GIS (Geographical Information System) maps to chart the development of the railway network over time much more accurately and completely than has hitherto been possible. The GIS dataset stems from collaboration by researchers at the University of Cambridge and a Spanish team, led by Professor Jordi Marti-Henneberg, at the University of Lleida. Our GIS dataset derives ultimately from the late Michael Cobb’s definitive work ‘The Railways of Great Britain. A Historical Atlas’. Our account of the development of the British railway system makes no pretence at originality, but the chapter does present some new findings on the economic impact of the railways that results from a project at the University of Cambridge in collaboration with Professor Dan Bogart at the University of California at Irvine.2 Data on railway developments in Scotland are included but we do not discuss these in depth as they fell outside the geographical scope of the research project that underpins this chapter. Also, we focus on the period up to 1911, when the railway network grew close to its maximal extent, because this was the end date of our research project. The organisation of the chapter is as follows. The next section describes the key characteristics of the British transport system before the coming of the railways in the nineteenth century. -

Bristol Arena

Bristol Arena bristoltemplequarter.com/arenaconsultation Bristol Arena Presentation • The planning applications: what they involve • What has changed since the pre-application consultation • Transport Assessment • Environmental Statement Questions bristoltemplequarter.com/arenaconsultation Location Arena Island bristoltemplequarter.com/arenaconsultation Bristol Arena: The full planning application Temple Meads Plaza Temporary car Arena park Service yard HCA bridge Cycle storage Accessible parking St. Philip’s footbridge bristoltemplequarter.com/arenaconsultation Bristol Arena: The full planning application Temple Meads Plaza Temporary car Arena park Service yard HCA bridge Cycle storage Accessible parking St. Philip’s footbridge bristoltemplequarter.com/arenaconsultation Bristol Arena: The outline planning application Mixed use development Plaza Arena Service yard HCA bridge Cycle storage Accessible parking St. Philip’s footbridge bristoltemplequarter.com/arenaconsultation The outline planning application Outline planning application • In the region of 19,000sqm mixed use development: 1,400sqm retail (use classes A1/A3) 8,200sqm offices (use class B1) 9,400sqm residential uses (class C3) • Affordable housing provision • New hard and soft landscaping, including new public realm riverside planting bristoltemplequarter.com/arenaconsultation Bristol Arena: What has changed? Design • New temporary event spaces • Upper façade design • Photo voltaic panels bristoltemplequarter.com/arenaconsultation Bristol Arena: Design changes bristoltemplequarter.com/arenaconsultation -

Marit Herit Resource Pack.Indd

Stories of the Severn Sea A Maritime Heritage Education Resource Pack for Teachers and Pupils of Key Stage 3 History Contents Page Foreword 3 Introduction 4 1. Smuggling 9 2. Piracy 15 3. Port Development 22 4. Immigration and Emigration 34 5. Shipwrecks and Preservation 41 6. Life and Work 49 7. Further Reading 56 3 Foreword The Bristol Channel was for many centuries one of the most important waterways of the World. Its ports had important trading connections with areas on every continent. Bristol, a well-established medieval port, grew rich on the expansion of the British Empire from the seventeenth century onwards, including the profits of the slave trade. The insatiable demand for Welsh steam coal in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries gave the ports of south Wales an importance in global energy supplies comparable to that of the Persian Gulf ports today. There was also much maritime activity within the confines of the Channel itself, with small sailing vessels coming to south Wales from Devon and Somerset to load coal and limestone, pilot cutters sailing out to meet incoming vessels and paddle steamers taking Bristolians and Cardiffians alike for a day out in the bracing breezes of the Severn Sea. By today, most of this activity has disappeared, and the sea and its trade no longer play such an integral part in the commercial activity of places such as Bristol and Cardiff. Indeed, it is likely that more people now go out on the Severn Sea for pleasure rather than for profit. We cannot and must not forget, however, that the sea has shaped our past, and knowing about, and understanding that process should be the birthright of every child who lives along the Bristol Channel today – on whichever side! That is why I welcome this pioneering resource pack, and I hope that it will find widespread use in schools throughout the area. -

Bristol Douglas Scott – Bristol Guide

Global Recruitment Guide to Bristol Douglas Scott – Bristol Guide Contents Introduction to Bristol 3 The Legal Market 4 Firms 4 Lifestyle 5 Shopping 5 Leisure & Local Attractions 5 Food & Drink 6 Quality of Life & Costs 7 Education 7 Safety 8 Weather 8 The Little Things 8 2 www.douglas-scott.co.uk Douglas Scott – Bristol Guide Introduction to Bristol Named the best city to live in according to The Sunday Times’ ‘Best Places to Live in Britain’ list in 2014, Bristol is a beautiful city with fantastic housing options, a buzzing nightlife, close to the tranquillity of the countryside and a variety of business options for professionals. 3 www.douglas-scott.co.uk Douglas Scott – Bristol Guide The Legal Market Bristol’s legal market is currently booming. A hub for top firms south of London with particularly strong contenders in the Property and Personal Injury markets, Bristol offers considerable opportunities to legal professionals in the south. Top 50 With a great number of Top 50 firms, Bristol’s legal market has seen considerable growth. Some of the top players include Simmons and Simmons, Irwin Mitchell, DAC Beachcroft and DWF, along with many more. Regional Firms The regional firms include success stories such as Clarke Willmott, Bevan Brittan and Ashfords, all carving a name for themselves as well established and prominent names in the market. New Entrants Foot Anstey is a recent entrant to the Bristol legal market, a particularly established regional firm who were previously awarded Legal Week’s Regional Law Firm of the Year. There are many other firms to consider, but this list should give you an idea of the extensive market that Bristol is home to. -

6 3 8 4 7 I 2

T S H THE G U BEARPIT R BOND ST O B L R A M PRESENTS 1 LEWINS MEAD T S U HIA Q N LP U I E O AD EE PHIL N N S S R Y T D A R I W T E W E S D N ST OA L I X R P L FA B D IR M A 2 E U F A T TRIANGLE STH M ER TE PP GA U NEW BR CASTLE PARK 27 FEB – 1 MAR, 5pm – 11pm OA D ST ST INE 3 Explore Bristol through light W A free event in Bristol city centre P A H R I K G S H T T S S T E N D OR P C S E T AS S N L I ST ICHO 5 T N S U G U BALDWIN ST A T S 4 COLLEGE BRANDON HILL GREEN KING STREET D K A O C R i A B R O H H C S L AN T E E W RE T S ANCHOR R OAD 6 7 E C 9 N I R QUEEN P SQUARE MILLENNIUM 8 SQUARE T HE GROVE ARTWORKS MILKBOTTLE MILKBOTTLE PINK OVERHEARD NEIGHBOURS CAGES SCREEN ENCHANTMENT IN BRISTOL COLLEGE GREEN, 1. QUAKERS FRIARS, 2. BANDSTAND, 3.CASTLE BRIDGE 4. WATERFRONT 5. PARK STREET CABOT CIRCUS CASTLE PARK NIMBES FRAME WILDLIFE ON THE WAVE-FIELD, INFORMATION HUT & NEBULAE PERSPECTIVE WATERFRONT VARIATION Q QUEEN SQUARE 6. WE THE CURIOUS 7. MILLENNIUM 8.ARNOLFINI, 9. QUEEN SQUARE i. -

TO LET 23,207 Sq Ft of Prime Waterfront Second Floor Office Space Introduction Location Description Amenities Floorplan Terms

TO LET 23,207 sq ft of prime waterfront second floor office space Introduction Location Description Amenities Floorplan Terms THE BUILDING Templeback is situated in a prime city centre location. It adjoins the floating harbour and has excellent access to the city’s key transport links and unrivalled amenities at Cabot Circus. The second floor comprises 23,207 sq ft and benefits from an exceptional Tenant fit out (completed in late 2016). Tenant’s in the building include Mott MacDonald, ADP, Jordans Limited and NFU Mutual. Introduction Location Description Amenities Floorplan Terms Getting around Local occupiers Well connected T S CASTLE PARK E M LANDING Q P E BRISTOL A CASTLE JACOB STREET R T L U S L T E T CROWN COURT L PARKK E T L E S E S S E TRENCHARD CASTLE I T T T H N ST PHILIP & N E R E STREET D R BRIDGE H T R E E R E I ST JACOB’S E E T R T P G S E CAR PARK E R A R W T Y S T S H T H CHURCH T S H R E S ST MARY LE PORT A Y N C N E T E A4018 S E I TH T N N CHURCH W N O E O T E W U T ’ T R O O R T S T T COLSTON THE OX E O R L S E T R HALL S T E L O E M O T A P A38 E T P H I L H PE R R VAULTS A C T M C H C BRISTOL O2 L E S ST GEORGE’S A S JU IL U N E N E 21 PA ACADEMY E R S B T BRISTOL TRA S L L T O WALKABOUT ROW PLAIN IGHT STREET IL V NAR T E ST RK C ET E E RE R ST REET R T ST E E C ST T T GE C S E HARL E E A RE T R EE E E S H GARDINER R TR S T BRANDON E TR D S A EESE HASKINS REET E ST E S A P ST T ET AR T HOMECENTRE OT R E E D L MR WOLFS E D 10 ORCHARD C STR B 15 A A TE R S R R 13 LA IS L P O U O 22 CH A NI TO SS R HANNAH MORE 3 S S