WRIGHT HILL RANCH OPEN SPACE PRESERVE MANAGEMENT PLAN Natural and Cultural Resources JANUARY 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archival Study for the Fish Habitat Flows and Water Rights Project

APPENDIX D Archival Study for the Fish Habitat Flows and Water Rights Project An Archival Study for the Fish Habitat Flows and Water Rights Project Mendocino and Sonoma Counties, California Eileen Barrow, M.A. June 6, 2016 An Archival Study for the Fish Habitat Flows and Water Rights Project Mendocino and Sonoma Counties, California Prepared by: _________________________________ Eileen Barrow, M.A. Tom Origer & Associates Post Office Box 1531 Rohnert Park, California 94927 (707) 584-8200 Prepared for: Sonoma County Water Agency 404 Aviation Santa Rosa, California 95407 June 6, 2016 ABSTRACT Tom Origer & Associates conducted an archival study for the Fish Habitat Flows and Water Rights Project, as requested by the Sonoma County Water Agency. This study was designed to meet requirements of the California Environmental Quality Act. Per the findings of the National Marine Fisheries Service (2008), the Sonoma County Water Agency is seeking to improve Coho salmon and steelhead habitat in the Russian River and Dry Creek by modifying the minimum instream flow requirements specified by the State Water Resources Control Board's 1986 Decision 1610. The current study includes a ⅛ mile buffer around Lake Mendocino, Lake Sonoma, the Russian River from Coyote Valley Dam to the Pacific Ocean, and Dry Creek from Warm Springs Dam to the Russian River. The study included archival research at the Northwest Information Center, Sonoma State University (NWIC File No. 15-1481); archival research at the Museum of Paleontology, University of California, Berkeley; examination of the library and files of Tom Origer & Associates; and contact with the Native American community. Documentation pertaining to this study is on file at the offices of Tom Origer & Associates (File No. -

Natural Resource Condition Assessment San Juan Island National Historical Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Natural Resource Condition Assessment San Juan Island National Historical Park Natural Resource Report NPS/SAJH/NRR—2020/2131 ON THIS PAGE View east from Mt. Finlayson at American Camp towards Lopez Island in distance. (Photo by Peter Dunwiddie) ON THE COVER Pacific madrone (Arbutus menziesii) on Young Hill, English Camp. (NPS) Natural Resource Condition Assessment San Juan Island National Historical Park Natural Resource Report NPS/SAJH/NRR—2020/2131 Catherin A. Schwemm, Editor Institute for Wildlife Studies Arcata, CA 95518 May 2020 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. The series supports the advancement of science, informed decision-making, and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series also provides a forum for presenting more lengthy results that may not be accepted by publications with page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

Ray Grass Perenne Pdf

Ray grass perenne pdf Continue Published in Temperate Climate and Cold Description: Unlike the annual rye grass, this variety is characterized by lasting over two years, being able to reach up to three or four years. It has a shallow fibrous radical system. It adapts to a temperate climate, does not tolerate high temperatures. Its growth is straight, with bright green leaves. It supports trampling, frost and is well competitive with other species. Soil: Suitable for all soils (except sandy soils), although it prefers fertile and moist soils and ph is close to neutrality. Nutrients and water: Requires irrigation, especially in summer and high fertilization. Shadow: Not suitable. Landing density: 3 to 15 kg / 100 m2. It is preferable to sow in early autumn, but can also be done in summer. Please note that the depth is no more than 2 cm. Cutting: 3 to 5 cm. Frequency: increased. Use: Widely used in parks and sports grounds, in mixes. It belongs to the family of grass, which is widely used all over the world and is considered one of the most valuable species of meadows. It is one of the most commonly used species both alone and in the mix. It has excellent tolerance to use, rapid germination (7 days in spring and 10 days in winter) and excellent installation speed. On the other hand, it is a species that is not drought-tolerant and requires high maintenance. Crossing different varieties has produced a wide range of varieties that differ in their characteristics, such as: tolerance to use, winter strength, color, resistance to disease and tolerance to heat and drought. -

Initial Study Appendix B

Uvas Road at Little Uvas Creek Bridge Replacement Project Biological Assessment Biological Assessment Uvas Road over Little Uvas Creek Bridge Replacement Project (37C-0095/37C-0601 [new]) Near Morgan Hill, Santa Clara County, California 04-SCL-0-CR Federal Project Number BRLO 5937(124) Caltrans District 04 November 2015 Biological Assessment Uvas Road over Little Uvas Creek Bridge Replacement Project (37C-0095/37C-0601 [new]) Near Morgan Hill, Santa Clara County, California 04-SCL-0-CR Federal Project Number BRLO 5937(124) Caltrans District 04 November 2015 STATE OF CALIFORNIA Department of Transportation and Santa Clara County Roads and Airports Department Prepared By: ___________________________________ Date: ____________ Patrick Boursier, Principal (408) 458-3204 H. T. Harvey & Associates Los Gatos, California Approved By: ___________________________________ Date: ____________ Solomon Tegegne, Associate Civil Engineer Santa Clara County Roads and Airports Department Highway and Bridge Design 408-573-2495 Concurred By: ___________________________________ Date: ____________ Tom Holstein Environmental Branch Chief Office of Local Assistance Caltrans, District 4 Oakland, California 510-286-5250 For individuals with sensory disabilities, this document is available in Braille, large print, on audiocassette, or computer disk. To obtain a copy in one of these alternate formats, please call or write to the Santa Clara County Roads and Airports Department: Solomon Tegegne Santa Clara County Roads and Airports Department 101 Skyport Drive San Jose, CA 95110 408-573-2495 Summary of Findings, Conclusions and Determinations Summary of Findings, Conclusions and Determinations The Uvas Road at Little Uvas Creek Bridge Replacement Project (proposed project) is proposed by the County of Santa Clara Roads and Airports Department in cooperation with the Office of Local Assistance of the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), and this Biological Assessment (BA) has been prepared following Caltrans’ procedures. -

Salmon Creek Estuary: Study Results and Enhancement Recommendations

Salmon Creek Estuary: Study Results and Enhancement Recommendations Appendices Appendix A: Salmon Creek Oral History Project Appendix B: Water Quality Figures Salmon Creek Estuary: Study Results and Enhancement Recommendations – Appendices June 2006 Appendix A: Salmon Creek History and Oral History Summary (Prepared by Kathleen Harrison) I. The Original Human Residents of Salmon Creek Watershed The human history of the Salmon Creek watershed must, of course, reach back to the original, indigenous people who were here long before the current era. It is established that Native Americans have been moving through and settling in California for at the very least 12,000 years. Archeological signs of ongoing habitation here in Salmon Creek watershed extend back at least 8,000 years. We know that the natives of this region were adept hunters, gatherers and managers of natural resources. The people of this region of North America did not practice agriculture, but they tended naturally existing populations of plants, trees, and terrestrial and aquatic animal life. Their goals for successful management were to maximize production of the foods and materials useful to humans, maintain a healthy balance in diverse communities of flora and fauna, support the natural cycles and longevity of wild populations, and to honor the many forces that they recognized in nature. They did this with various documented methods of land management. Annual or periodic late-season burning effectively removed brush without killing established trees, prevented the accumulation of detritus that encourages bacterial, viral and fungal diseases in trees, and fertilized the soil with ash, encouraging growth and production of seeds and acorns. -

More Mesa Plant Guide

More Mesa Plant Guide Coastal Woodfern Miniature Lupine Sky Lupine Arroyo Lupine Dryopteris arguta 1 Lupinus bicolor 2 Lupinus nanus 3 Lupinus succulentus 2 Pinpoint Clover White-tipped Clover Deerweed Desert Lotus Trifolium gracilentum 4 Trifolium variegatum 5 Acmispon glaber 3 Acmispon strigosus 3 Chaparral Lotus California Blackberry Toyon California Rose Acmispon grandiflorus Rubus ursinus 6 Heteromeles arbutifolia 3 Rosa californica 3 grandiflorus 3 Sticky Cinquefoil California Coffeeberry Stinging Nettle Pigmyweed Drymocallis glandulosa Frangula californica 6 Urtica dioica 6 Crassula aquatica 7 glandulosa 3 Pygmy Stonecrop Narrowleaf Milkweed Seacliff Wild Willow Dock Crassula connata 3 Asclepias fascicularis 3 Buckwheat Rumex salicifolius 8 Eriogonum parvifolium 6 Willow Weed Dotted Knotweed California Goosefoot Pacific Pickleweed Persicaria lapathifolia 9 Persicaria punctata 10 Chenopodium Salicornia pacifica 11 californicum 3 Spearscale Big Saltbush Saltmarsh Sand- Prostrate Amaranth Atriplex prostrata 6 Atriplex lentiformis spurrey Amaranthus blitoides 13 lentiformis 3 Spergularia marina 12 Redmaids Miner's Lettuce Short Styled Thistle California Brittlebush Calandrinia ciliata 6 Claytonia perfoliata 3 Cirsium brevistylum 3 Encelia californica 3 Horseweed Marsh Baccharis Coyote Brush Mule Fat Erigeron canadensis 6 Baccharis glutinosa 6 Baccharis pilularis 3 Baccharis salicifolia 6 California Sagebrush Mugwort Western Ragweed California Cudweed Artemisia californica 3 Artemisia douglasiana 2 Ambrosia psilostachya 14 Pseudognaphalium -

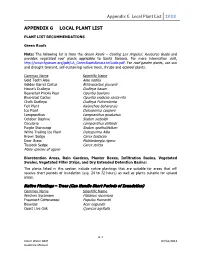

Appendix G Local Plant List 2013 APPENDIX

Appendix G Local Plant List 2013 APPENDIX G LOCAL PLANT LIST PLANT LIST RECOMMENDATIONS Green Roofs Note: The following list is from the Green Roofs – Cooling Los Angeles: Resource Guide and provides vegetated roof plants applicable to Santa Barbara. For more information visit, http://www.fypower.org/pdf/LA_GreenRoofsResourceGuide.pdf. For roof garden plants, use sun and drought tolerant, self-sustaining native trees, shrubs and ecoroof plants. Common Name Scientific Name Gold Tooth Aloe Aloe nobilis Golden Barrel Cactus Echinocactus grusonii Hasse’s Dudleya Dudleya hassei Beavertail Prickly Pear Opuntia basilaris Blue-blad Cactus Opuntia violacea santa-rita Chalk Dudleya Dudleya Pulverulenta Felt Plant Kalanchoe beharensis Ice Plant Delosperma cooperii Lampranthus Lampranthus productus October Daphne Sedum sieboldii Oscularia Lampranthus deltoids Purple Stonecrop Sedum spathulifolium White Trailing Ice Plant Delosperma Alba Brown Sedge Carex testacea Deer Grass Muhlenbergia rigens Tussock Sedge Carex stricta Many species of agave Bioretention Areas, Rain Gardens, Planter Boxes, Infiltration Basins, Vegetated Swales, Vegetated Filter Strips, and Dry Extended Detention Basins: The plants listed in this section include native plantings that are suitable for areas that will receive short periods of inundation (e.g. 24 to 72 hours) as well as plants suitable for upland areas. Native Plantings – Trees (Can Handle Short Periods of Inundation) Common Name Scientific Name Western Sycamore Platanus racemosa Freemont Cottonwood Populus fremontii -

Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University Botanical Studies Open Educational Resources and Data 9-17-2018 Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park James P. Smith Jr Humboldt State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Smith, James P. Jr, "Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park" (2018). Botanical Studies. 85. https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps/85 This Flora of Northwest California-Checklists of Local Sites is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources and Data at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Botanical Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CHECKLIST OF THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF THE REDWOOD NATIONAL & STATE PARKS James P. Smith, Jr. Professor Emeritus of Botany Department of Biological Sciences Humboldt State Univerity Arcata, California 14 September 2018 The Redwood National and State Parks are located in Del Norte and Humboldt counties in coastal northwestern California. The national park was F E R N S established in 1968. In 1994, a cooperative agreement with the California Department of Parks and Recreation added Del Norte Coast, Prairie Creek, Athyriaceae – Lady Fern Family and Jedediah Smith Redwoods state parks to form a single administrative Athyrium filix-femina var. cyclosporum • northwestern lady fern unit. Together they comprise about 133,000 acres (540 km2), including 37 miles of coast line. Almost half of the remaining old growth redwood forests Blechnaceae – Deer Fern Family are protected in these four parks. -

Tidal Marsh Vegetation of China Camp, San Pablo Bay, California Peter R

AUGUST 2012 Tidal Marsh Vegetation of China Camp, San Pablo Bay, California Peter R. Baye1 ABSTRACT vegetation. Narrow high tidal marsh ecotones that borders terrestrial grasslands are locally dominated China Camp (Marin County, California) preserves by creeping wildrye (Elymus triticoides) and Baltic extensive relict stands of salt marsh vegetation rush (Juncus balticus), mostly on south-facing slopes. developed on a prehistoric salt marsh platform with Brackish tidal marsh ecotones above ordinary high a complex sinuous tidal creek network. The low salt tides are associated with freshwater discharges from marsh along tidal creeks supports extensive native groundwater and surface flows. Brackish marsh eco- stands of Pacific cordgrass (Spartina foliosa). After tones support large clonal stands of sedge, bulrush, hydraulic gold mining sedimentation, the outer and rush vegetation (Carex praegracilis, C. barbarae, salt marsh accreted. It consists of a wave-scarped Bolboschoenus maritimus, Juncus phaeocephalus, pickleweed-dominated (Sarcocornia pacifica) high Schoenoplectus acutus), intergrading with terrestrial salt marsh terrace, with a broad fringing low marsh freshwater wetlands and salt marsh. The terrestrial dominated by S. foliosa, including intermittent, vari- ecotone assemblages at China Camp are comparable able stands of alkali-bulrush (Bolboschoenus mari- with those of other prehistoric tidal marshes in the timus). Most of the extensive prehistoric salt marsh San Francisco Estuary, but China Camp lacks most plains within the tidal creek network also support native clonal perennial Asteraceae and halophytic mixed assemblages of S. pacifica, but high marsh annual forbs of the region’s remnant high tidal marsh zones along tidal creek banks support nearly continu- ecotones. Few globally-rare salt marsh plant popula- ous linear stands of gumplant (Grindelia stricta) and tions have been reported from China Camp within saltgrass (Distichlis spicata) with more diverse salt the National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR) and marsh forb assemblages. -

National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands 1996

National List of Vascular Plant Species that Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary Indicator by Region and Subregion Scientific Name/ North North Central South Inter- National Subregion Northeast Southeast Central Plains Plains Plains Southwest mountain Northwest California Alaska Caribbean Hawaii Indicator Range Abies amabilis (Dougl. ex Loud.) Dougl. ex Forbes FACU FACU UPL UPL,FACU Abies balsamea (L.) P. Mill. FAC FACW FAC,FACW Abies concolor (Gord. & Glend.) Lindl. ex Hildebr. NI NI NI NI NI UPL UPL Abies fraseri (Pursh) Poir. FACU FACU FACU Abies grandis (Dougl. ex D. Don) Lindl. FACU-* NI FACU-* Abies lasiocarpa (Hook.) Nutt. NI NI FACU+ FACU- FACU FAC UPL UPL,FAC Abies magnifica A. Murr. NI UPL NI FACU UPL,FACU Abildgaardia ovata (Burm. f.) Kral FACW+ FAC+ FAC+,FACW+ Abutilon theophrasti Medik. UPL FACU- FACU- UPL UPL UPL UPL UPL NI NI UPL,FACU- Acacia choriophylla Benth. FAC* FAC* Acacia farnesiana (L.) Willd. FACU NI NI* NI NI FACU Acacia greggii Gray UPL UPL FACU FACU UPL,FACU Acacia macracantha Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd. NI FAC FAC Acacia minuta ssp. minuta (M.E. Jones) Beauchamp FACU FACU Acaena exigua Gray OBL OBL Acalypha bisetosa Bertol. ex Spreng. FACW FACW Acalypha virginica L. FACU- FACU- FAC- FACU- FACU- FACU* FACU-,FAC- Acalypha virginica var. rhomboidea (Raf.) Cooperrider FACU- FAC- FACU FACU- FACU- FACU* FACU-,FAC- Acanthocereus tetragonus (L.) Humm. FAC* NI NI FAC* Acanthomintha ilicifolia (Gray) Gray FAC* FAC* Acanthus ebracteatus Vahl OBL OBL Acer circinatum Pursh FAC- FAC NI FAC-,FAC Acer glabrum Torr. FAC FAC FAC FACU FACU* FAC FACU FACU*,FAC Acer grandidentatum Nutt. -

DRAFT OAEC NATIVE PLANT LIST FERNS and FERN ALLIES

DRAFT OAEC NATIVE PLANT LIST FERNS and FERN ALLIES: Blechnaceae: Deer Fern Family Giant Chain Fern Woodwardia fimbriata Dennstaedtiaceae: Bracken Fern Bracken Pteridium aquilinum Dryopteridaceae: Wood Fern Family Lady Fern Athyrium filix-femina Wood Fern Dryopteris argutanitum Western Sword Fern Polystichum muitum Polypodiaceae: Polypody Family California Polypody Polypodium californicum Pteridaceae: Brake Family California Maiden-Hair Adiantum jordanii Coffee Fern Pellaea andromedifolia Goldback Fern Pentagramma triangularis Isotaceae: Quillwort Family Isoetes sp? Nuttallii? Selaginellaceae: Spike-Moss Family Selaginella bigelovii GYMNOPSPERMS Pinaceae: Pine Family Douglas-Fir Psuedotsuga menziesii Taxodiaceae: Bald Cypress Family Redwood Sequoia sempervirens ANGIOSPERMS: DICOTS Aceraceae: Maple Family Big-Leaf Maple Acer macrophyllum Box Elder Acer negundo Anacardiaceae: Sumac Family Western Poison Oak Toxicodendron diversilobum Apiaceae: Carrot Family Lomatium( utriculatum) or (carulifolium)? Pepper Grass Perideridia kelloggii Yampah Perideridia gairdneri Sanicula sp? Sweet Cicely Osmorhiza chilensis Unidentified in forest at barn/deer fence gate Angelica Angelica tomentosa Apocynaceae: Dogbane or Indian Hemp Family Apocynum cannabinum Aristolochiaceae Dutchman’s Pipe, Pipevine Aristolochia californica Wild Ginger Asarum caudatum Asteraceae: Sunflower Family Grand Mountain Dandelion Agoseris grandiflora Broad-leaved Aster Aster radulinus Coyote Brush Baccharis pilularis Pearly Everlasting Anaphalis margaritacea Woodland Tarweed Madia -

Biological Resources Report City of Fort Bragg Wastewater Treatment Plant Upgrade

BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES REPORT CITY OF FORT BRAGG WASTEWATER TREATMENT PLANT UPGRADE 101 West Cypress Street (APN 008-020-07) Fort Bragg Mendocino County, California prepared by: William Maslach [email protected] August 2016 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES REPORT CITY OF FORT BRAGG WASTEWATER TREATMENT PLANT UPGRADE 101 WEST CYPRESS STREET (APN 008-020-07) FORT BRAGG MENDOCINO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA PREPARED FOR: Scott Perkins Associate Planner City of Fort Bragg 416 North Franklin Street Fort Bragg, California PREPARED BY: William Maslach 32915 Nameless Lane Fort Bragg, California (707) 732-3287 [email protected] Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... iv 1 Introduction and Background ............................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose ......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Scope of Work ............................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Location & Environmental Setting ................................................................................................ 1 1.4 Land Use ........................................................................................................................................ 2 1.5 Site Directions ..............................................................................................................................